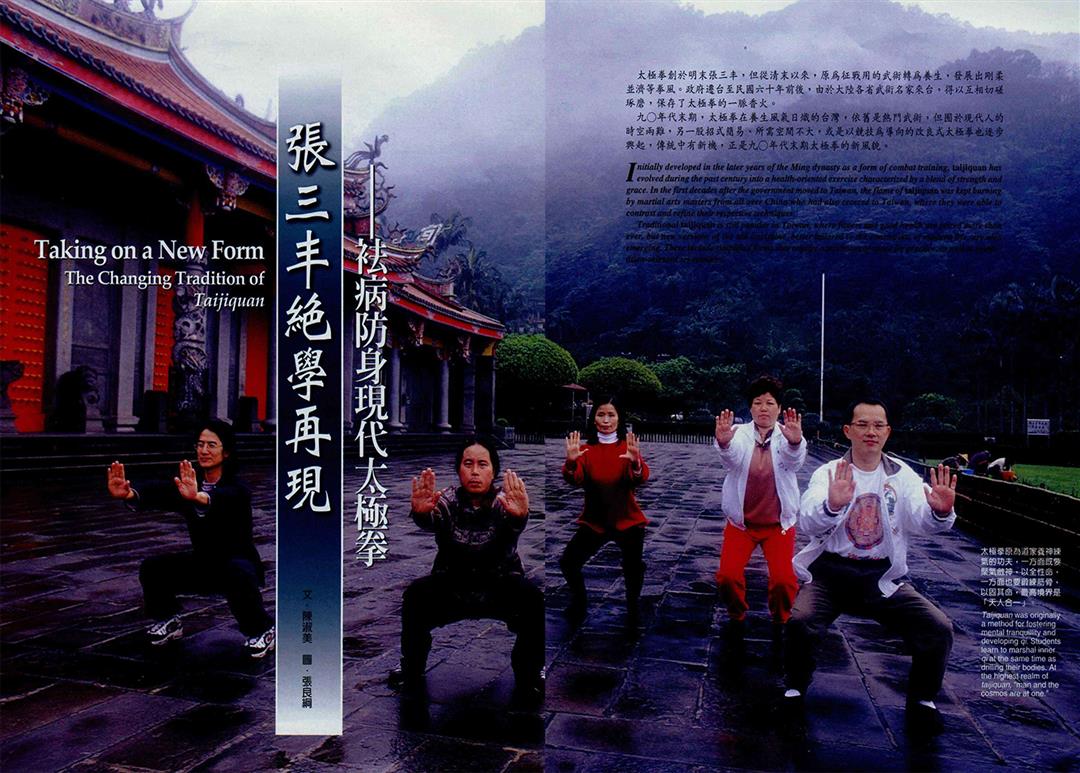

Taking on a New Form- The Changing Tradition of Taijiquan

Jackie Chen / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Christopher MacDonald

May 1999

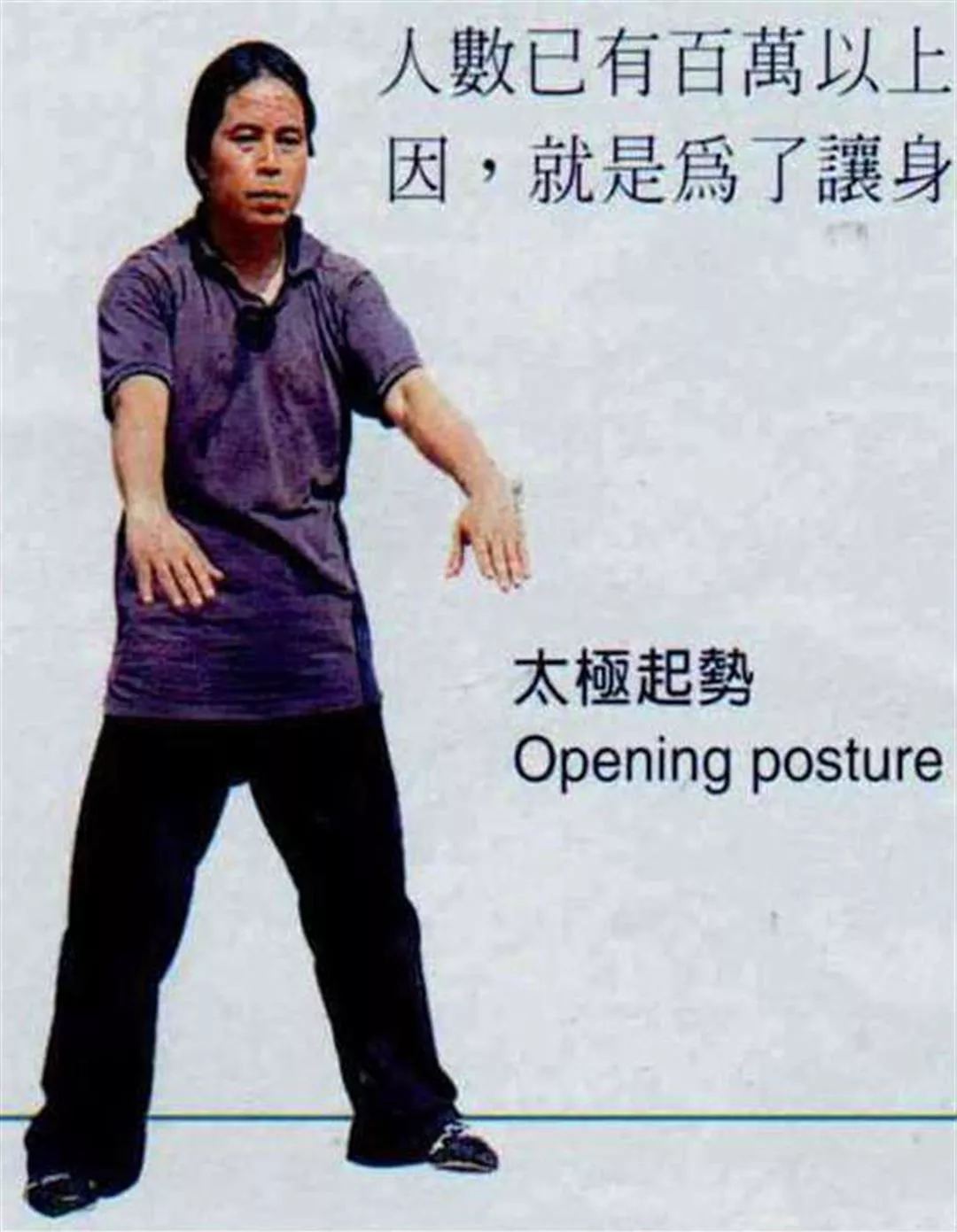

Opening posture.

Initially developed in the later years of the Ming dynasty as a form of combat training, taijiquan has evolved during the past century into a health-oriented exercise characterized by a blend of strength and grace. In the first decades after the government moved to Taiwan, the flame of taijiquan was kept burning by martial arts masters from all over China who had also crossed to Taiwan, where they were able to contrast and refine their respective techniques.

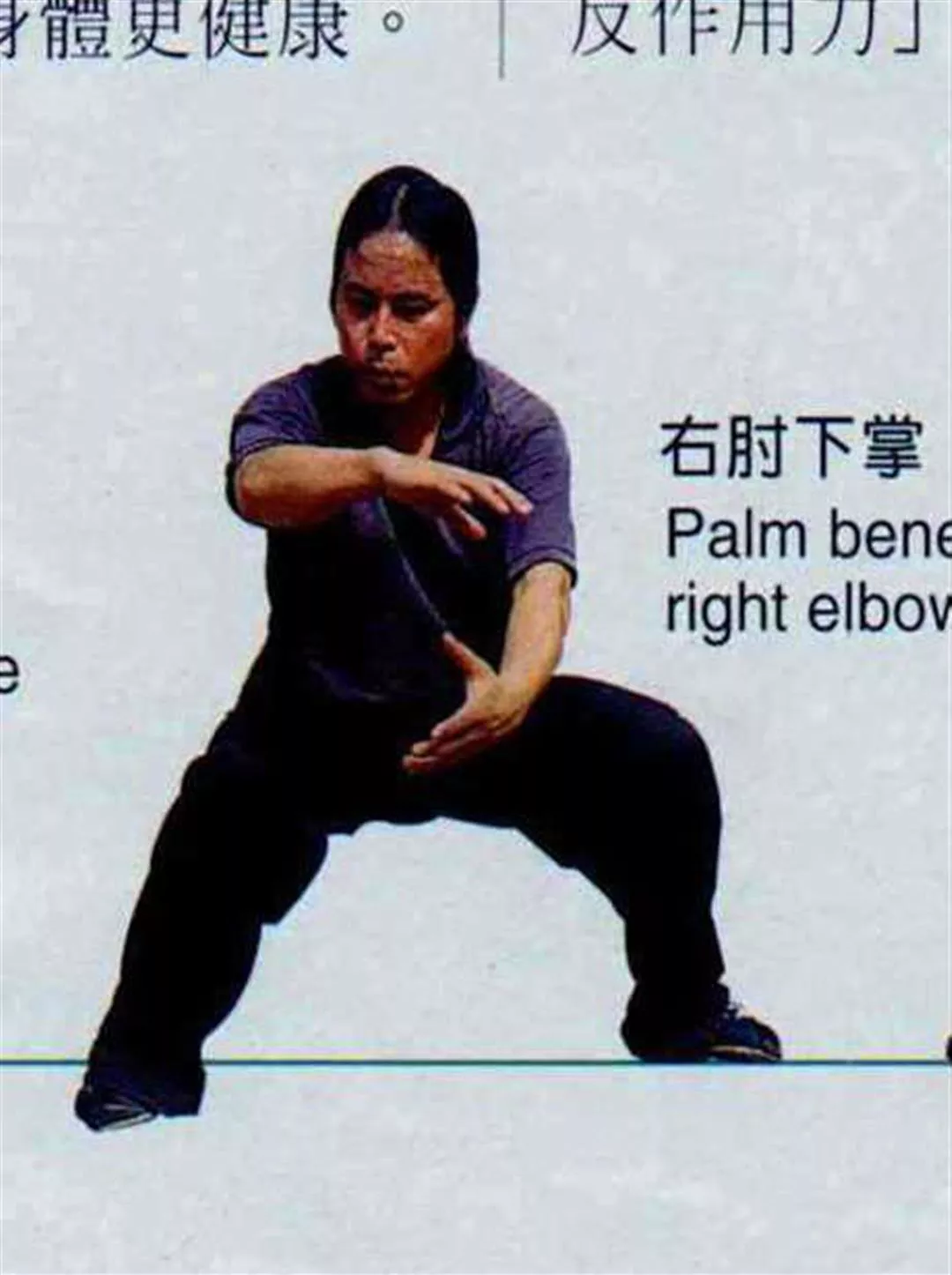

Palm beneath right elbow.

Traditional taijiquan is still popular in Taiwan, where fitness and good health are prized more than ever, but new versions of the old discipline, better tailored to the constraints of modern life, are also emerging. These include simplified forms that require a minimum of space for practice, as well as competition-oriented set-routines.

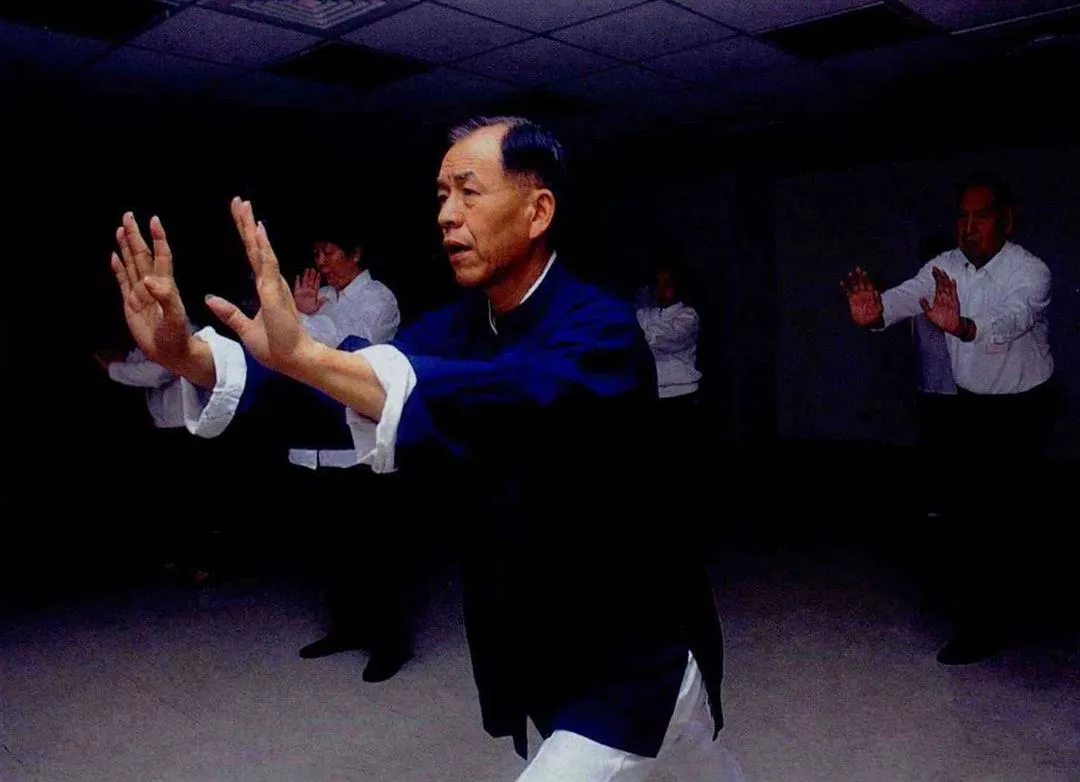

Chang Liang-wei, head coach at Taipei's Taiji-daoyin Study Association, wears a string of honey-amber beads on his wrist as a mark of appreciation for the former pupil who presented him with this, his first such gift since establishing the Association's gym.

The origins of the gift were as follows: When she was eight or nine years old, the daughter of Dr. Lai, chief physician in orthopedics at the Provincial Chutung Hospital, fell down stairs and was left with a crooked spine. The deformity worsened, and by the time she reached junior high school her whole body was twisted, virtually into an S-shape. Though an orthopedist himself, Dr. Lai was helpless. The best he could do was to take his daughter for daily therapy with a specialist in Chinese bone-manipulation, but the girl's condition still did not improve.

One day Dr. Lai saw some people practicing taiji-daoyin in the park, putting their joints through a routine of bizarre rotations, and he promptly wondered if exercises like this might help with his daughter's spine. He contacted the Taiji-daoyin Association in Taipei, and then took his daughter and the rest of the family to start classes at the Association's gym, even though they were just about to emigrate to the US in pursuit of medical treatment.

After 10 days of taiji-daoyin training, a peculiar thing happened. "The atrophied part of the girl's back filled out, as if infused with qi," says Chang Liang-wei, and her spine became visibly less distorted.

With arrangements already made for his daughter's treatment in the US, Dr. Lai and his family decided to emigrate as planned, but to carry on practicing taiji-daoyin in America. Chang is certain that with taiji-daoyin and the appropriate therapy, there will be further improvement in the girl's condition.

The string of beads on Chang's wrist was a gift from Dr. Lai and his daughter on the eve of their departure for the US.

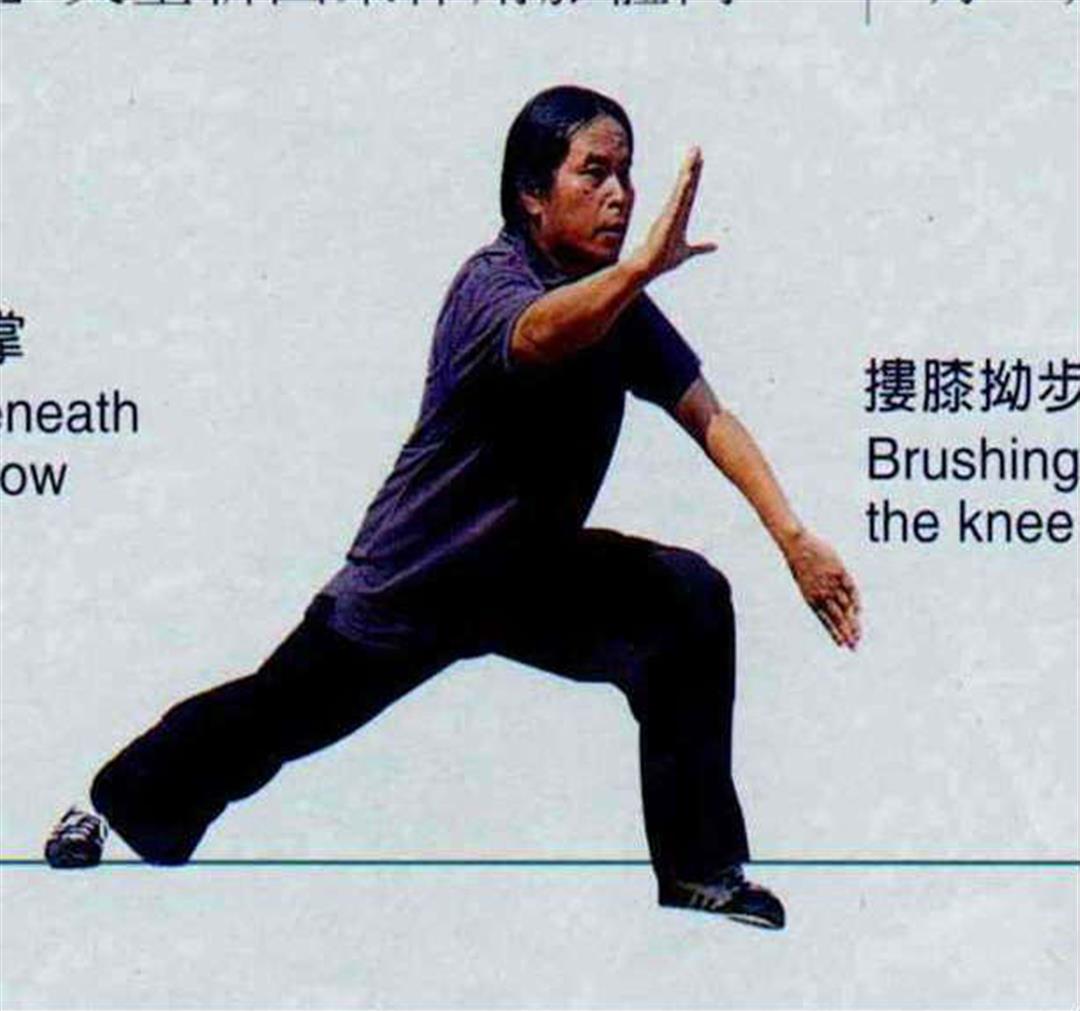

Brushing around the knee.

Posture and relaxation

According to Chen Chia-yuan, associate professor in martial arts at Chinese Culture University's Sports Department, "Over 80% of people who practice taijiquan [Tai Chi] do so for the sake of their health," and ROC Taichichuan Association statistics put the total number of taijiquan learners in Taiwan at over one million people, with health and fitness as their primary motivation.

Wang Peng-kai, 28, injured his spine when he was in the army, and says that strenuous exercise leaves him feeling "virtually paralyzed" all over. Furthermore, his body registers any change in the weather. Damp, chilly conditions are particularly difficult for Wang, who finds the only remedy at such times is to soak away the strain in a hot bath.

Five months ago Wang took up taijiquan. "Before, I often felt blood building up along my spine because of the injury to my lower back and long periods spent sitting at the office." Once he began learning taijiquan and absorbing fundamentals like keeping the tail-bone tucked in, the waist loose and the hips "seated," Wang gradually began to alter his daily posture. As a result of this, combined with breathing drills for the circulation of qi, Wang found his back muscles becoming "more flexible and pliant, with less pressure between the vertebrae," and noted steady improvement in his lower back pain.

Sufferers of chronic ailments often experience the therapeutic efficacy of taijiquan in different ways, but at a deeper level, it always comes down to a combination of posture and relaxation.

Chen Chang-po, a researcher at Academia Sinica's Institute of Zoology, notes that "relaxation" is the starting point for taijiquan. Apart from loosening up one's skin and flesh, this also means relaxing ligaments and nerves within the body, and in particular reducing the amount of impulses passing through the nervous system. Relaxing the side of the neck, the hollows of the collar-bone and the inner thighs is also very good for promoting blood flow to the head and limbs. As Chen describes it, what is commonly referred to as "qi" is a sensation of something coursing through the body like a kind of pressure wave, resonating from the fluid-filled inner vessels to the fleshy surface of the body, and penetrating to the inner organs and brain.

People who do taijiquan tend to use abstruse formulations like "borrowing energy from the universe" and "connecting with cosmic energy" to describe the phenomenon of qi. Chen Chang-po elaborates on the idea of energy transfer by applying the concept of "action" and "reaction."

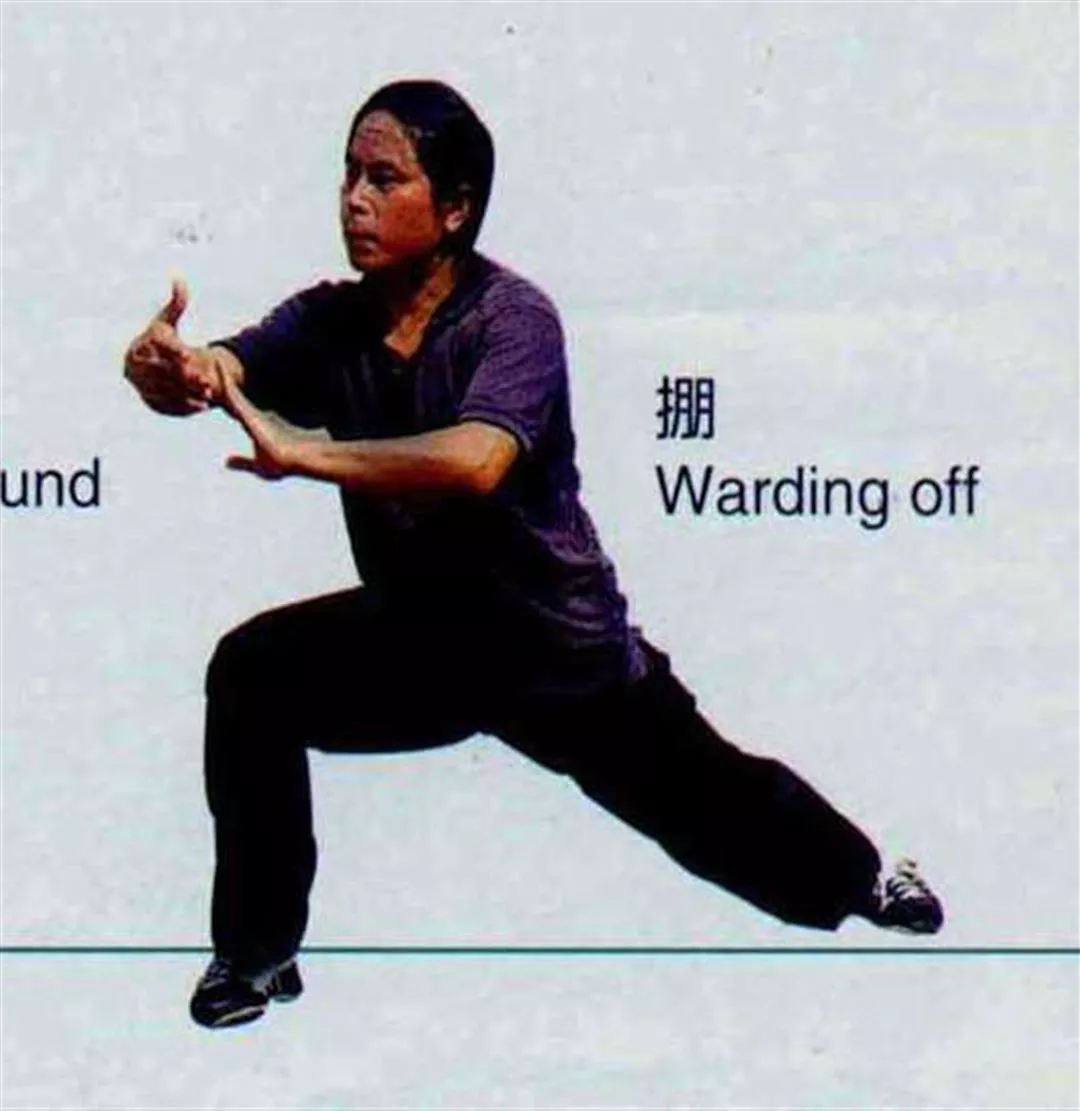

Warding off.

As he explains, taijiquan lowers the body's center of gravity by relaxing the muscles, so creating an "action," which in turn generates a "reaction" from the ground, returning energy to the body and increasing the activity of qi. "Taijiquan simply relaxes the body, 'using the mind to activate qi,' and then specifies certain physical movements, 'using qi to exercise the body,' increasing pressure within the fluids in the body so as to build up fitness," says Chen. Activating qi by the mind

With its emphasis on "developing qi to relax the body," and its loose, supple, slow physicality, taijiquan is a contrast to the usual types of exercise favored by today's well-fed, sedentary city slickers with their hectic lifestyles-activities such as jogging, gym workouts, and aerobics, which contract the muscles and quicken the pulse. Ninety-year-old Huang Yu-chen, who has been doing taijiquan for over six decades, remarks that "for people today, exercise mostly means running and jumping. It's not bad, and exercises the body just the same, but jumping about leaves you agitated and restless, and when the qi hits the brain you get giddy, whereas taijiquan quiets your heart and lets the qi settle downwards."

Letting the qi sink, keeping the pelvis steady, and having strong legs and waist-these are the keys to taijiquan. The Classic of Taijiquan informs us: "Unless the soles of your feet [from which qi wells up] are rooted to the ground you have no control over your waist, and even if you study until you drop it will be to no avail." In other words, if you don't master how to make your qi "sink," you could train for a lifetime and it would all be in vain.

What accounts for this phenomenon called "qi," and what is the underlying principle? Chen Chang-po points out that people normally generate qi throughout their daily lives, by the beating of the heart, circulation of the blood, breathing, gastrointestinal peristalsis and muscle contraction. Walking, running and jumping all produce qi, but when people are under pressure or feeling tension the flow of qi gets disrupted-which is when relaxation exercises are needed to restore the balance.

For the great majority of people, muscle tension makes it difficult to detect the flow of qi within them, but changes in qi become clearer once the body is relaxed. As Chen Chang-po explains, long-time learners of taijiquan gradually begin to sense how qi follows a course through the more relaxed channels between muscles and along the ligaments, but gets blocked wherever it encounters stiffness. These blockages have to be loosened before the qi can flow onto the next stiff part. After one has trained for a long time at "relaxing the qi," any growth or reduction in pressure within the body triggers an automatic adjustment in the level of qi. This, according to Chen, explains why "taijiquan experts rarely lose their temper and don't have high blood pressure, because when blood pressure starts to rise it automatically gets lowered again."

Circulating qi can even be applied to "massage" certain organs by altering the volume of blood within them, promoting fluid flow and oxygenation, and can also be used to fend off chills and cure colds by dilating blood-vessels in the throat and nasal passages, increasing blood flow and thereby drawing more warmth and oxygen to the area.

People who have been doing taijiquan for a number of years tend to have healthy complexions and seldom fall ill. Furthermore, exposure to traditional Daoist and Confucian concepts in the course of their training-"through technique, into dao"-has benefited them in terms of how they handle affairs, both at work and at home.

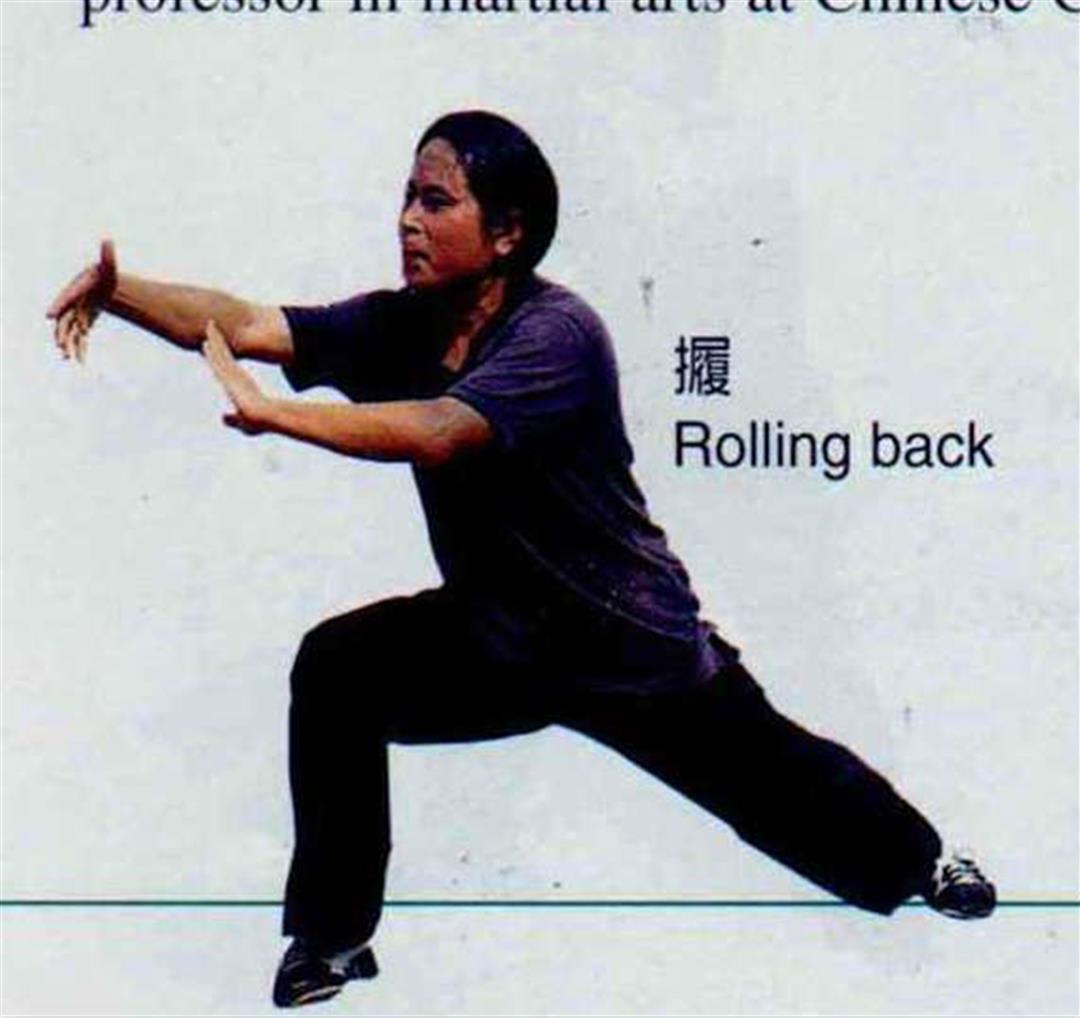

Rolling back.

Huang Kuo-chung, alternate committee member at the Taichichuan Association, explains that the word quan in taijiquan, means "cultivating the hands," which in other words means "exercise," something that takes place at the level of technique. And taiji means "the natural way"-standing erect and centered, being impartial and unbiased, neither lacking nor in excess, adhering to one position-in other words the way of the natural world, and the way of the human being. Or in short: moral cultivation, the very purpose of human life. Long-lived heroes

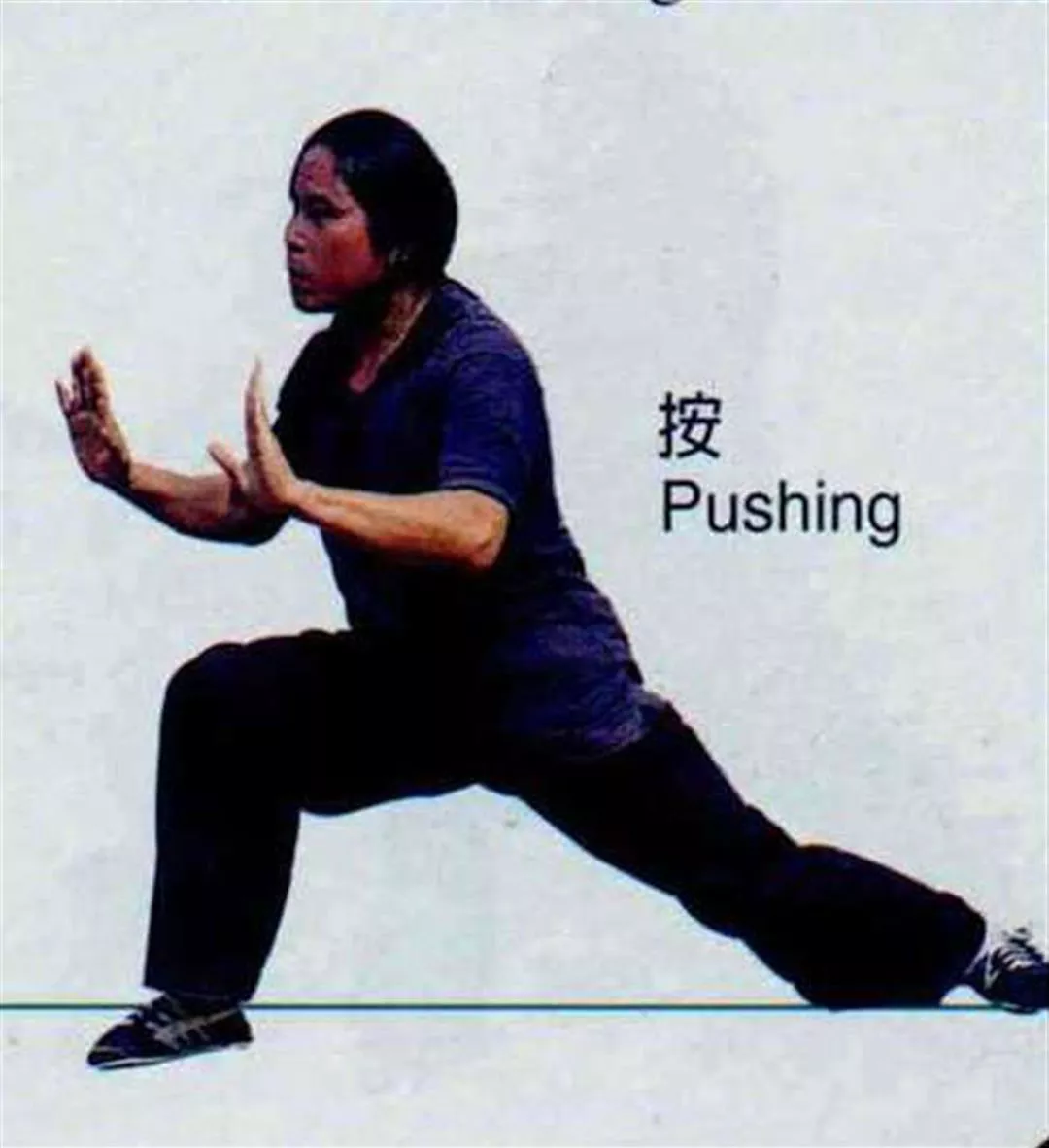

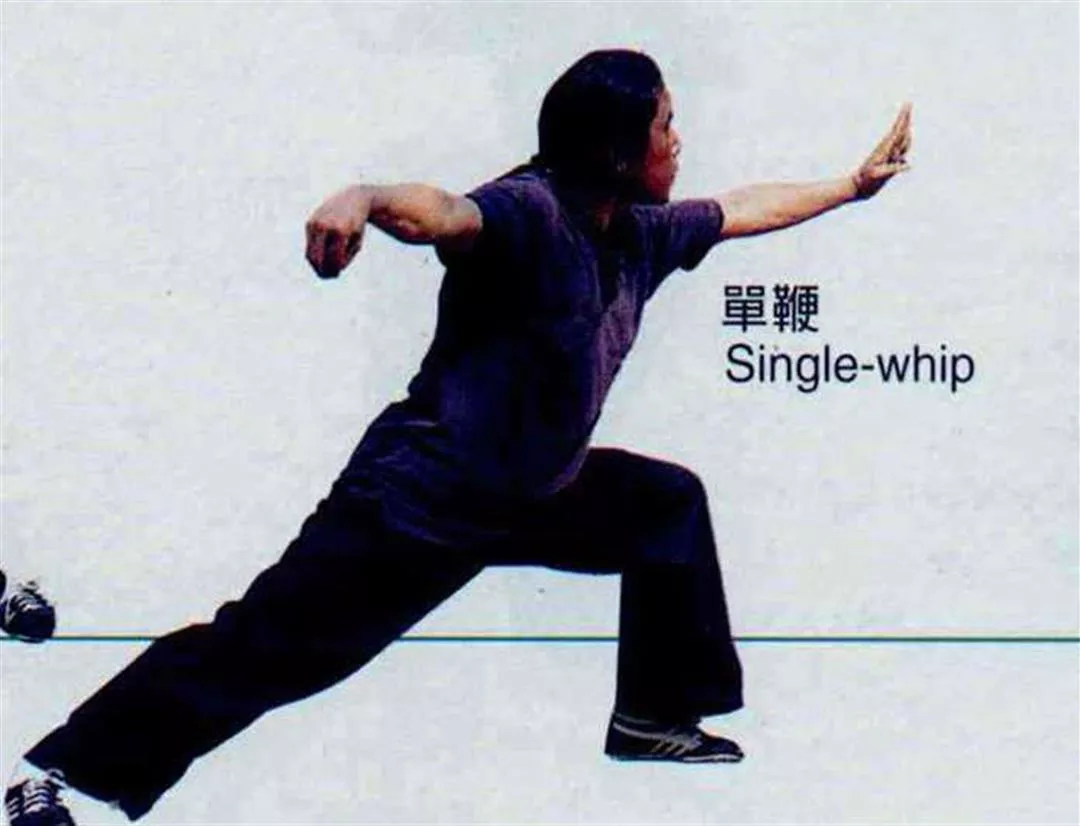

Taijiquan originally developed out of a form of Daoist exercise for cultivating qi and attaining mental repose. It was during the late Ming dynasty that Chang Sanfeng, the founder of taijiquan, devoted himself to combining the mysterious art of controlled-breathing from qigong with a variety of established combat techniques, based around principles of "change": yin and yang, motion and stillness. The result was a set of 13 fundamental taijiquan movements: warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, pulling down, quick reaction, elbowing, shouldering, stepping forward, stepping back, looking round, gazing forward, and remaining stable. Designed in imitation of the cosmic "taiji principle"-as represented in the yin-yang symbol-and drawing on Daoist breathing techniques, these movements convert slowness into speed and rigidity into suppleness, using the external form of the body to exercise the innate qi within.

The object of traditional combat training was for war and self-defense. When military officers retired and moved back to their original homes, they brought their skills to a wider population, and thus martial arts began to spread. In the agricultural society of old, most people led plain lives, without time for such pursuits or the money to pay for training, which is why martial arts were generally passed down only in the families of the wealthy.

Since the late Qing dynasty, when China came under assault from the gunboats of the Western powers, techniques that were once practiced for combat have evolved into a form of fitness training. Once it was considered better to avoid risking sacrifice in unarmed combat when possible, the primary objective of taijiquan turned to fostering good health. As the Classic of Taijiquan says, it should be borne in mind that "Great heroes are not made by combat skills alone-they also enjoy long lives."

Historical records trace the emergence of several different styles of taijiquan since the late Qing dynasty, including the Chen, Yang, Wu and Sun schools. Yen Chen, himself a long-time practitioner of the art, points out that while Chen-style taijiquan emphasizes power penetration and a blend of force with gentleness, Yang-style attaches more importance to smoothness and fluidity of motion. Yet in all other essentials such as keeping centered and erect, and deploying strength symmetrically, there is little to separate the two styles.

Most of the taijiquan that is taught in Taiwan today represents traditions that originated from all over China, and came across from the mainland with the arrival of some two million soldiers and civilians in 1949.

Chen Chia-yuan, associate professor at Chinese Culture University, notes that many martial arts aficionados came to Taiwan after Retrocession, and taijiquan was also boosted by the energetic advocacy of top government officials who themselves were practitioners of the discipline, including former presidential adviser Ho Ying-chin, and former minister of justice Ku Feng-hsiang. This contributed to the rapid development of taijiquan in Taiwan through the 1960s and 1970s, in contrast to the situation on the mainland during the Cultural Revolution, when practicing taijiquan was regarded as a manifestation of deep-rooted feudal habits.

"I still recall that 20 or 30 years ago, famous taijiquan masters often gave talks in a meeting room at the Legislative Yuan," says Wang Hua-chung, a retired former member of the Examination Yuan, and currently a board member with the Taichichuan Association. It was those talks that first encouraged him to seek out a teacher and train to the level that he is at today.

Pushing.

Many of today's taijiquan teachers in their forties and over have stories to tell about their own experiences studying with the masters that came to Taiwan from the mainland in 1949. Kowtow to the master

"I studied under my master for 30 years before I was formally inducted as his apprentice," says Lai Wu-hsiung, a national coach based at the Shulin Martial Arts Association. Lai's master, Wang Chien-feng, inherited the line of teaching in (Hebei province's) Cangzhou school of taijiquan from Master Huo Zhaolu, as well as from Wang Songting, a highly regarded martial arts master of the late Qing dynasty. As Lai recalls, when he and his fellow pupils were studying with Wang Chien-feng, "Master taught only three moves each lesson, and the students were only allowed to watch-we couldn't ask questions. Master made extremely strict demands on the pupils: if you got something wrong you might even get smacked in the head. Quite a few students were driven away by treatment of this kind." Lai became Wang's first official apprentice in Taiwan, and is respectfully referred to as "Senior Apprentice" by the other pupils.

Lai, who now passes on to others what he has acquired from his teacher, doesn't resort to physical and verbal punishment but is still very strict with his pupils. In addition to their training duties, he expects his students to observe the martial artist's spirit of chivalry: "Where faith and virtue are, righteous qi is found."

In 1990s Taiwan, crowds of people can be seen practicing taijiquan daily, in the early morning and at dusk, at outdoor spaces such as CKS Memorial Hall and the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. "Taijiquan never goes out of date," says Wang Hung-tao, who teaches taijiquan at several government agencies. Nevertheless, taijiquan is predominantly the preserve of people in their middle or later years, and the martial arts clubs that were so popular on campuses around Taiwan for a while in the 1970s are these days unable to attract new students.

In order to promote taijiquan to a wider public, experts in the field are now working to update traditional forms with new versions such as "taijizhang" ("taiji-palm")-which has been developed by Wang Hung-tao and is built around a series of key moves designed to drill the hands, eyes, body, waist, and feet. "The whole form takes about 20 minutes to complete, and requires the space of just four 30cm-square floor tiles for practice," says Wang. It is fully tailored to the needs of young people and nine-to-fivers.

Single-whip.

Another new style is "taiji-daoyin," a 12-movement routine refined from traditional taijiquan by the well-known practitioner Hsiung Wei. Taiji-daoyin, which is easy to begin learning and requires a minimal amount of space for practice, has already been adopted as a keep-fit exercise by major corporations such as Acer, as well as being extended into modern dance and applied as a surprising new form of "Chinese-style dance workout." (See accompanying article for more on taiji-daoyin.) The competitive route

Huang Kuo-chung says that taijiquan in Taiwan today is developing in three main directions. First is taijiquan as a national exercise, practiced by the old folks at the crack of dawn in parks and sports fields around the island, in forms that typically consist of 13, 24, 37 or 64 moves. Although there are some experts among them, most "are not too thorough about their movements," remarks Huang Kuo-chung, "and their chief aim is to get a bit of exercise." This is the main type of taijiquan promoted around Taiwan by branches of the Taichichuan Association and local taijiquan organizations.

The second type includes the various schools of taijiquan for which there exists a direct line of instruction from the founder to the present day, like that being taught by Lai Wu-hsiung. Such schools generally maintain their own gym for teaching purposes, where master and pupils can work together on their particular discipline. A basic skill level is usually required for joining such a school, as well as some sort of payment for the teacher. As Huang says, "there are certain entry requirements, which may include kowtowing to the master as an expression of respect." These schools concentrate on their own particular styles, for the purpose of passing on the art.

The third type is "competition-form taijiquan," which includes the 42-move form created for the Asian Games, along with specific competition forms for each of the Yang, Chen, Wu and Sun styles.

At the 1990 Asian Games in Beijing, taijiquan became an official international sport for the first time. Since then, the lure of prize money and international tournaments has spurred numerous top martial artists to take up taijiquan, elevating the discipline to a new peak during the past decade.

A new 42-move form was established for the Asian Games, with contestants being judged on their facility in the form, including points such as whether a leg is raised high enough or if movements performed from a low squat are executed with sufficient power. The competitive element has attracted many young people to taijiquan, but has also provoked controversy within martial arts circles.

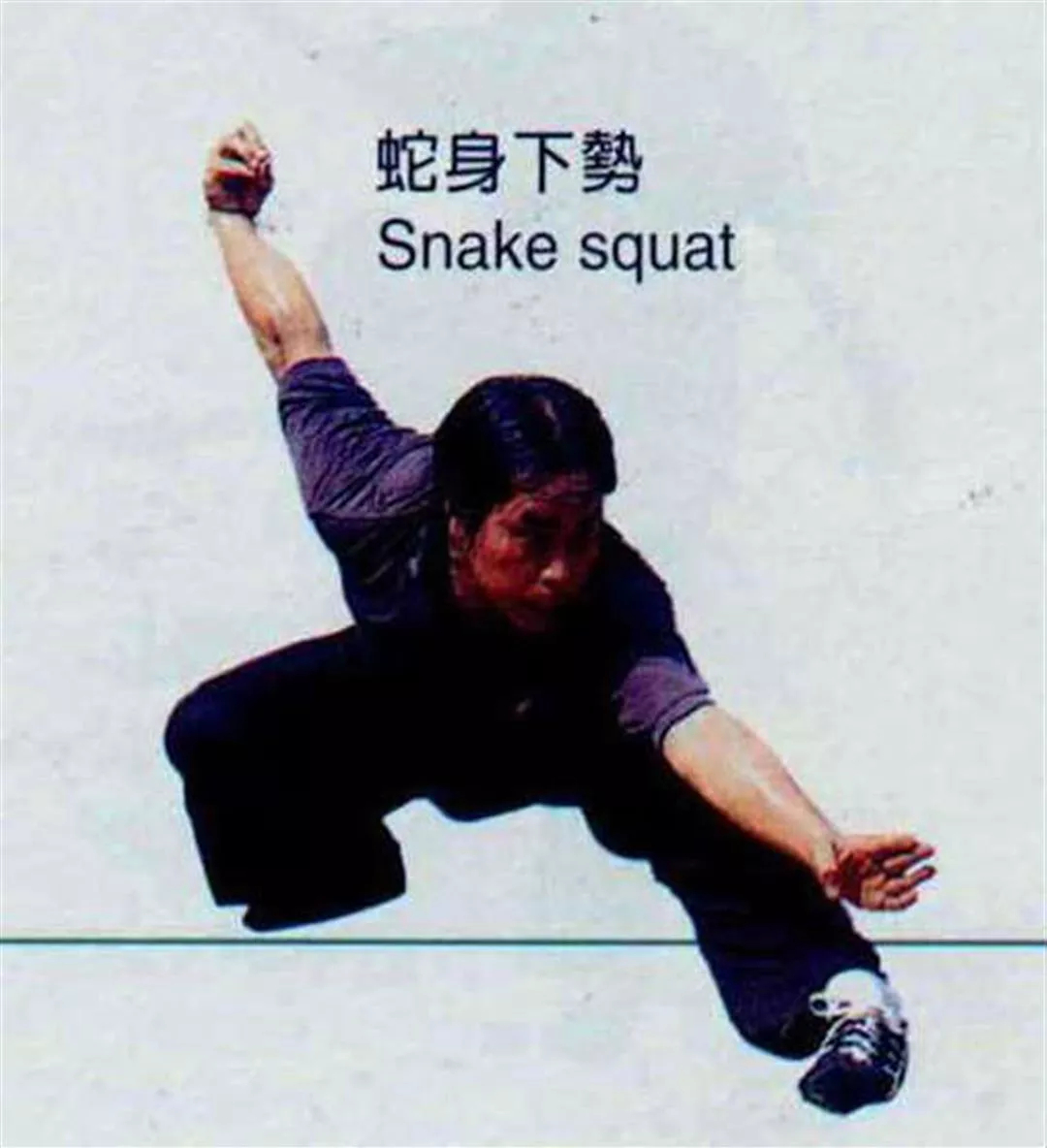

Snake squat.

Fist of life

As Huang Kuo-chung notes, the Asian Games 42-move form, which "looks good and only takes about five or six minutes to complete," is better suited for promoting taijiquan than the 108-move Yang-style form that most people know about.

But for serious practitioners, there is an over-emphasis in the 42-move form on external appearance, including leg movement, compared with the traditional Yang, Chen and other styles of taijiquan in which the stress is on "inner skill." In the traditional forms, the strikes of taijiquan are performed within a "small frame," whereas "large frame" movements-which tend to over-extend the limbs-are played down. Says Huang: "An inch more elevation equals an inch more risk-one knock and you could be down on the ground." Yet in the 42-move form, the contestant's leg has to be raised to waist height at least. According to Chan Ming-shu, gold medalist at the 1998 Asian Games in Bangkok, the idea of this "is to create a stage effect."

There are many in the taijiquan community who have serious reservations about the use of competition to promote taijiquan.

One issue is whether the 42-move form, with its over-emphasis on externals, will branch further and further away from traditional taijiquan of the Yang, Chen and other schools.

As Yen Chen, taijiquan coach at the "Art of Life Academy" in Chungli points out, the true significance of taijiquan lies in the fact that it enables "cultivation of both the inner and the outer." There are two interpretations of what is meant here by "the inner": inner power, and moral cultivation. As Yen remarks: "Inner cultivation is at the very core of Chinese culture. If we don't talk about inner cultivation then we see the surface but miss the very essence. If you only concentrate on external form, on technique, then what emerges is the wrong kind of skill. What taijiquan is fundamentally about is pursuing the richness of life. There is no connection between competing in technique simply for the sake of fame and gain, achieving growth in one's life." As Yen warns: "Prolonged training of this kind is liable to harm the body eventually."

What is the secret of taijiquan? The late Ku Feng-hsiang, in his book The True Meaning of Taijiquan, writes: "Taijiquan can enable one to totally overcome gain and loss, to be at one with the world, to think deeply and freely, not to be overwhelmed by worries, to take delight in one's own pleasures, to be at home with one's own abilities, and not to know 'if I am here for taijiquan, or taijiquan is here for me.'"

So how about it-are you going to give it a try?

Snake squat.

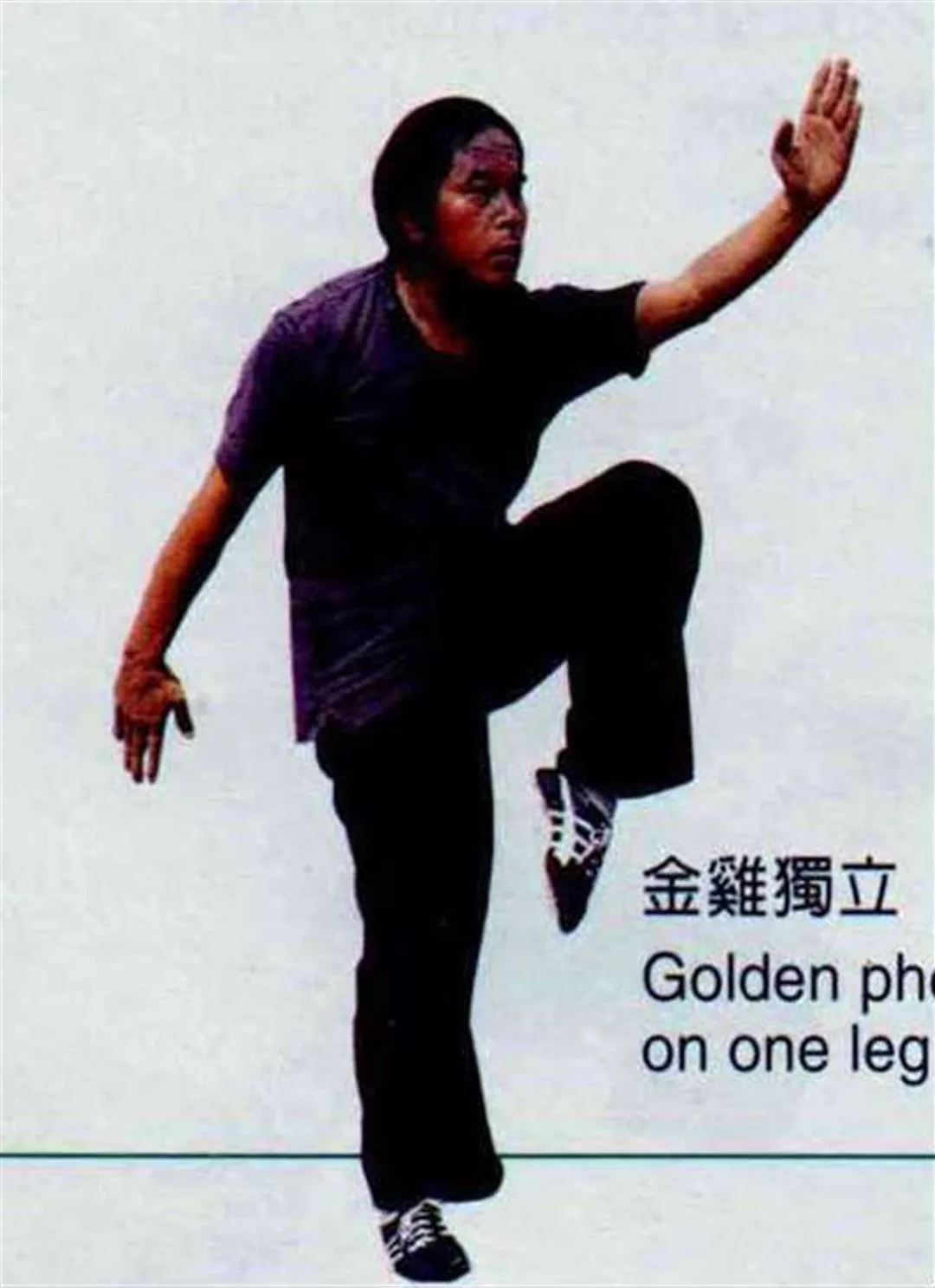

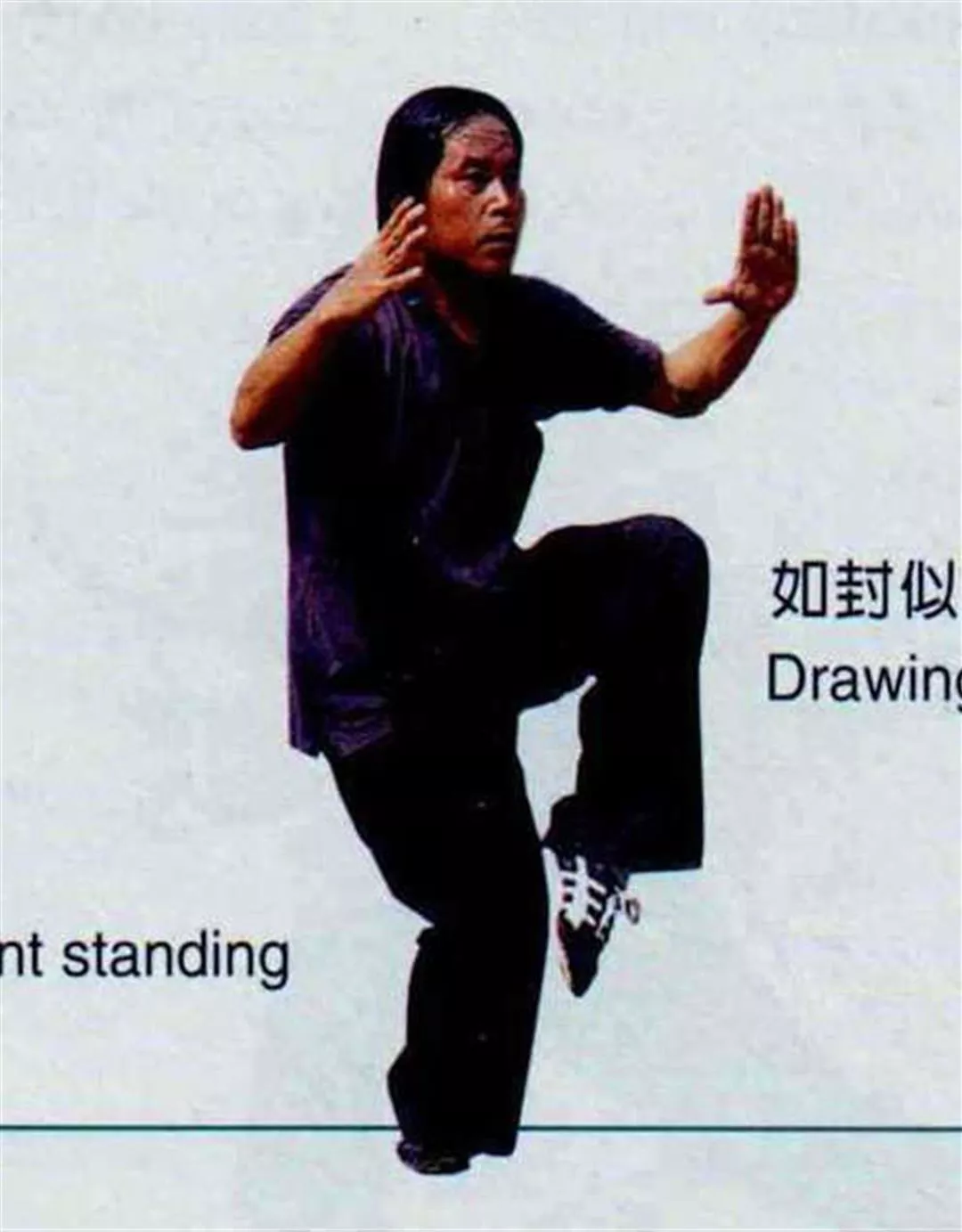

Drawing in.

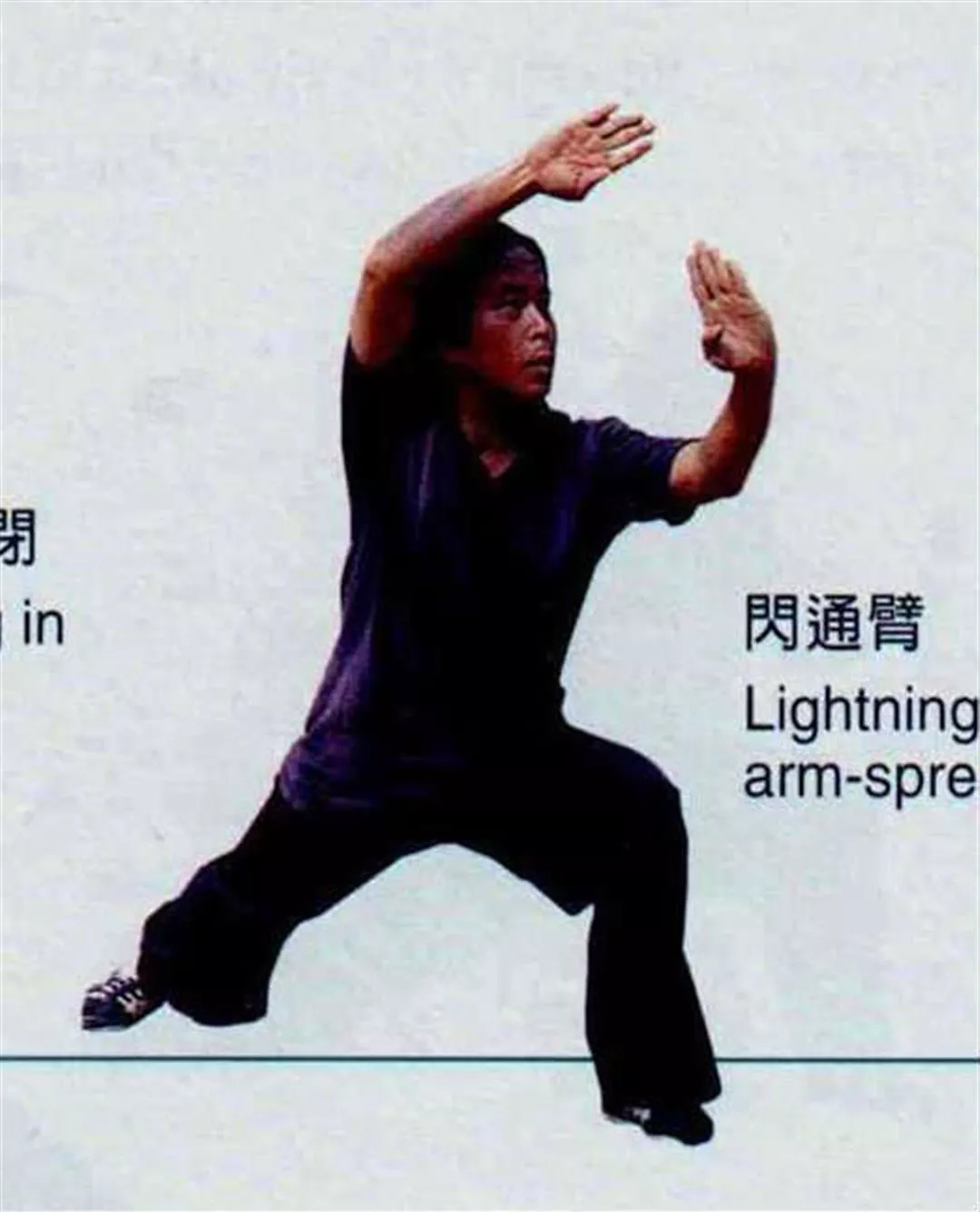

Lightning arm-spread.

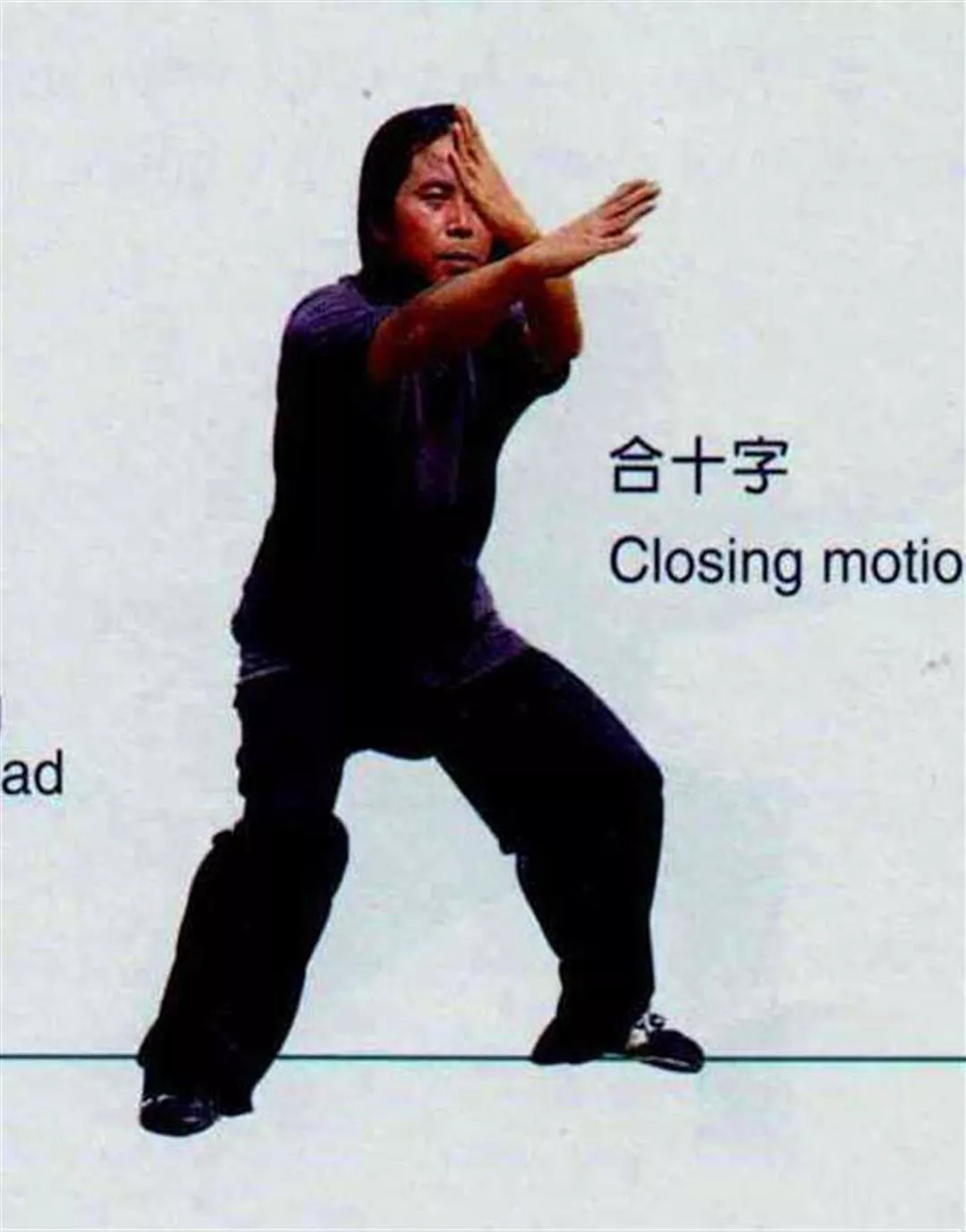

Closing motion.

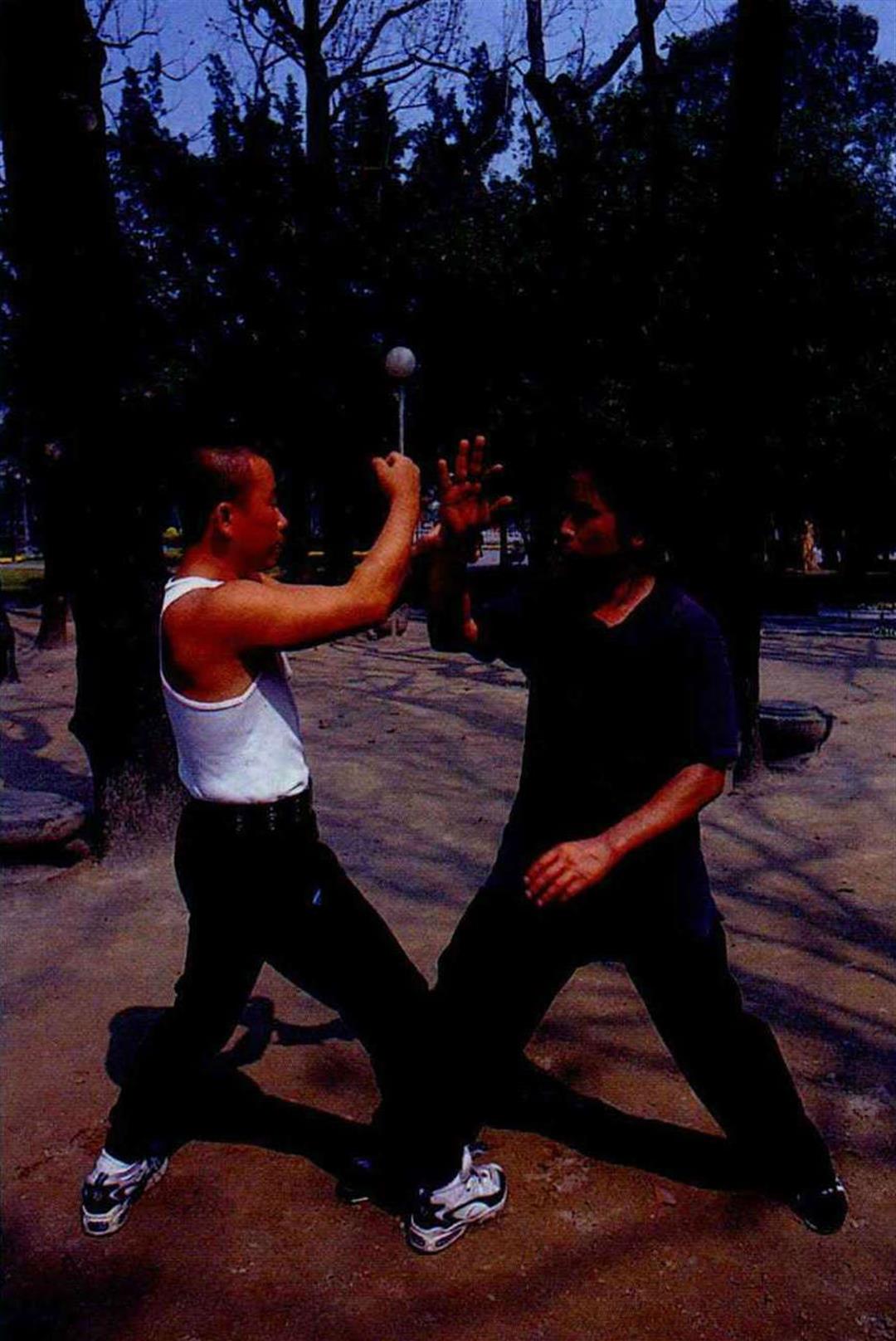

Pushing hands is a unique part of taijiquan. "Where my opponent is rigid, I am soft; this is called 'moving away.' Where I follow as my opponent drops back, this is called 'sticking.' Rapid movement brings a rapid reaction, slow movement draws a slow response"--good principles for life as well as for taijiquan.

Pushing hands is a unique part of taijiquan. "Where my opponent is rigid, I am soft; this is called 'moving away.' Where I follow as my opponent drops back, this is called 'sticking.' Rapid movement brings a rapid reaction, slow movement draws a slow response"--good principles for life as well as for taijiquan.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)