Urban Renewal: A Bottom-Up Approach

Vito Lee / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Paul Frank

August 2006

In the past, apartment buildings in Taiwan have often been put up by "single-project companies" that vanished even before all the units were sold--a practice that seriously undermined the quality of construction. But in recent years, a new breed of single project companies have emerged in Taiwanese cities which promise to make residential environments more livable and to remold and revitalize our cityscapes.

In several respects, these new single project companies clearly lack professional qualifications: they possess no construction expertise and have no experience in handling property transfers--a key element of the house building process. They are made up of residents (property rights owners) whose most important asset besides their property rights is a common vision for their future homes. As residential complexes fall into disrepair, the residents of those located in good areas have jumped on the "urban renewal" bandwagon. Quite apart from reductions on land tax and other levies, floor space incentives, "rights conversions" and other preferential policies, the appreciation potential of such real estate makes developers drool with envy. As a result, it may now be possible to transform the old housing market framework, in which government and real estate developers took the initiative and house buyers played a passive role, into one in which residents take the initiative in building their own homes.

In Taipei, it takes wage earners an average of nine years' income to buy their own home. Compared to the average home buyer, there is no question that people who are able to exchange their low-cost old house for a new house because of urban real-estate saturation are very fortunate. Taiwan's cities, whose residential landscapes invite so much public condemnation, are placing high hopes in them. People who build their homes with their own hands put more effort into them. They care about their home's market value, but even more about its "residential quality."

There is reason to hope. The rebirth of our cities may be on the horizon.

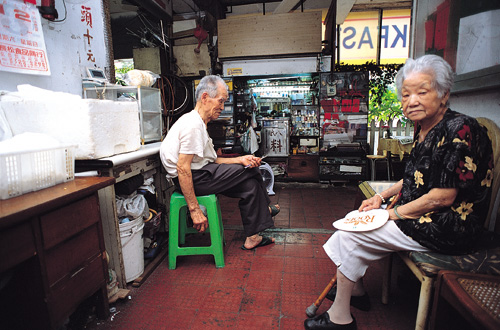

Everyone wants a new home: Mrs. Hsu, who hails from Qingdao in mainland China, is getting on in age, lives on the fourth floor, and cannot climb more than a few steps without panting. Mr. Tu, a native of Ningbo who lives on the second floor, resents the fact that he and his family of three are squeezed into an apartment of less than 14 ping (one ping is 3.3 square meters or 35.3 square feet). Then there is Ms. Chen, who is always dressed to the nines and frowns whenever she sees a beat-up old motorcycle in the corridor. When she enters or leaves the building, she lowers her head in shame because in an area full of five-star hotels, foreign companies, and posh apartments, this dilapidated building is a bit of a loss of face.

Several families do their cooking in the corridor next to the courtyard. To get to the stairwell one has to pick one's way past gas stoves, dirty bowls and chopsticks, and plastic buckets filled with cooking leftovers. Looking through the stairwell windows, one can see famous landmarks in the nearby Hsinyi Project Area, including Taipei 101, the World Trade Center, Taipei City Hall, the Grand Hyatt, and several department stores and movie theaters. But compared to those bright new buildings, this circular-shaped six-story apartment block looks pretty wretched, an impression that is made even worse by row upon row of stove vents protruding into dim corridors which make the air smell of grease. Families live cheek by jowl. Along the two-meter-wide corridor, there are shoe racks (which Taiwanese people customarily place outside their front door) as well as a mind-boggling array of objects: a discarded plastic tricycle, a bicycle, an old TV set, a refrigerator, an air-conditioner, an archaic typewriter, and a chest of drawers that must have seen better days.

"It's almost 40 years old, but this building also has its strong points. It rode the 921 Earthquake without a crack," smiles Mr. Tan, who lives on the fourth floor.

Settling property questions in Prosperity Residences is particularly thorny not only because the residents' property rights are muddled, but also because the parking lot, corridors, and common area facilities are owned by the Taipei City Government.

It's our building

The residents of "Prosperity Residences"--a multi-family public housing building with more than 500 14- to 18-ping apartments arranged in a circular pattern--have a love-hate relationship with their home. When it was built in 1973, the Hsinyi Project Area was just patches of weeds; amidst the glitter of today's Hsinyi Project Area, this building occupying something over 2000 ping of land presents a woefully dilapidated appearance.

"All things considered, I think urban renewal is a good thing," says 33-year-old Mr. Tan. "At least new buildings are bigger and have elevators, which is good even if it means you have to buy a parking space separately."

On the first Saturday in July, Mr. Tan and more than 200 fellow residents go to the city council building to attend a public hearing on a proposed "urban renewal project run by residents." Mr. Tan represented his father, a bedridden retired serviceman from Hunan Province who needs four people to carry him up and down the stairs in his wheelchair. But resident representatives were not the only participants: architects, housing developers, and mortgage banks looking for business opportunities also sent agents to the public hearing.

"I've been to dozens of hearings like this over the past five years. They used to be organized by housing developers," says Mr. Tan. This time it's different. Billy Wang, one of the initiators of the urban renewal proposal for Prosperity Residences, is himself also a resident. This is the first public hearing since he submitted a draft plan for the renewal project to the Taipei City Urban Redevelopment Office.

"I also came to listen," says Mr. Tu, known as "Lord Tu" to his neighbors. In the past, housing developers also proposed a redevelopment plan, but "they only offered 1.35 ping for each existing ping. But the 14 ping we have now is the actual floor area. After their conversion the extra square footage would have included 30% common area, which would come to about same floor area. The terms they offered were just unacceptable."

Most residents of Prosperity Residences are elderly, and a large proportion live in households with no fixed income. Getting a new apartment would naturally be a godsend for them, but the part of the cost of rebuilding that they would have to bear themselves, and having to move and pay rent somewhere else while the work was being done, makes it difficult for many of them to summon up enthusiasm for the renewal project.

In view of the appreciation potential of the land on which the building stands, besides proposing a joint building venture, some developers are also contemplating buying the entire apartment block and rebuilding it. But the land price of a prime location such as this is high and few developers have the capacity to buy out every owner and rebuild from scratch. An even greater deterrent is the time and effort it takes to persuade more than 500 owners to sell. Like rich families that have come down in the world, the residents are living in a rundown building on a prime location. Developers can only "stare at but not eat" this real estate pie, which promises to become even more valuable in future. "We've had Thomas Huang, Chen Shui-bian and now Ma Ying-jeou as mayors. During each tenure the city government came to improve things, but we're still where we started," says Mr. Huang, a Mucha resident who rents out his 17-ping apartment for NT$12,000 a month.

Mrs. Hsu, a resident in her eighties who chats with friends and neighbors in front of the building every day, says, "Urban renewal? We've been hoping for too long."

Renewal Prelude

"In the past the leading role was played by the government and real estate developers. The Urban Renewal Act, which was enacted in 1998, was meant to encourage owners to take the initiative," says Pien Tyzz-shuh, the first director of Taipei City's Urban Redevelopment Office, the nation's first such office. "Now residents are putting forward their own proposals and are organizing themselves to initiate dialogue and solve property rights problems. This may be a turn for the better."

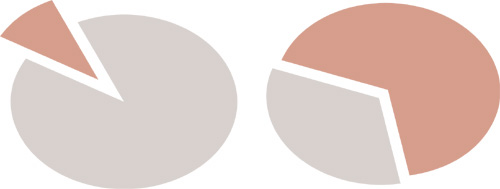

To encourage residents to come forward and engage in dialogue, they have to be shown how they stand to benefit. "Once this 2000-ping parcel is redeveloped, and with the city government's relaxed floor space index requirements as an incentive for urban renewal, the total floor area will be 24,000 ping. At NT$500,000 per ping, the total value will be NT$12 billion," explains Billy Wang. "If the building costs are NT$5 billion...."

In the name of renewal

An urban environment is a living organism. Overdevelopment causes degeneration, the most visible manifestation of which is the gradual dilapidation of buildings and concomitant issues such as public order, public health, and fire hazard problems that menace people's life and property.

Government departments responsible for urban development periodically estimate future demands, but all too often their plans cannot keep up with the pace of change. "What we now need is urban renewal that integrates plans drawn up by public authorities with civic initiatives, to improve residents' lives as quickly as possible," says Pien Tyzz-shuh. "The most direct renewal method is to tear down old houses and build new ones."

According to Taipei City Government statistics, at the end of 2003 there were 1.34 million four-story buildings and 920,000 five and six-story buildings in the city older than 25 years, all of which will be targeted for redevelopment.

In fact, the city government began to undertake urban renewal by means of "zone expropriation" as early as two decades ago. The Taipei City Urban Renewal Ordinance was passed in 1998 to encourage residents to initiate projects of their own. A variety of incentives are beginning to show results: 165 renewal project applications have been submitted to date. But so far, most renewal projects have involved military dependents' villages and government employee housing; very few privately initiated projects are underway.

The main difficulty in urban renewal projects is to offer owners terms that will persuade them to rebuild. "Unless you have a small building with few owners and a simple property rights structure, balancing the interests of different owners--such as a store front, a top-floor apartment, and a mid-level apartment--can be a very difficult proposition," says Sheng Yang Real Estate managing director Chien Po-yin. "We're currently looking at a number of urban renewal projects, as they are called. In fact, most of them are plans to rebuild apartment blocks, either by housing developers who buy the land or through joint ventures with landowners who own multiple units in a block."

"Of course, this is an effective way to improve residents' quality of life," says Chang Chin-oh, professor of land economics at National Chengchi University. "But if the site is small we can't really expect a renewal project to produce external benefits such as a better urban environment, increased land tax revenues, and architecture that is more pleasing to the eye." To spread the positive effects of urban renewal, Taipei's Urban Renewal Ordinance stipulates that except in extraordinary cases, for a private urban renewal project to be approved, residents must live on the same street block and the land area must be at least 2000 square meters (around 605 ping).

Though located in a prime downtown area near Taipei 101 (facing page), Prosperity Residences is gradually falling into disrepair, as this furred-up pipe illustrates all too well.

Economies of scale

An inch of land along an MRT line is an inch of gold, which is what makes this area unaffordable. From Prosperity Residences we can walk to Taipei City Hall MRT station in ten minutes and reach Hsinpu station in Panchiao 25 minutes thereafter. Walking through a long market gallery, past a series of obstacles formed by street vendors, cars, motorcycles, and crowds of people, we finally step into the sunlight.

Situated near the MRT and the East-West Expressway, Panchiao's Mingtsui Borough stretches over six hectares (18,000 ping). Along its two main streets and dozens of alleys there are mostly four- and five-story residential buildings constructed in the 1960s and 70s. Considering the completion of various transportation infrastructure projects, resulting in a large increase in potential value, 57-year-old five-time borough warden Hsu Wen-hung has big hopes for community regeneration.

Since October of last year, Hsu has called a series of borough meetings to explain his plan to Mingtsui's 1,600 families. Their response was enthusiastic. When news of Taiwan's biggest citizen-initiated urban renewal project spread, Hsu Wen-hung became the best-known borough warden on the island.

Lighting a Long Life cigarette in his office, which has a leaking roof, Hsu Wen-hung says, "I'm only interested in solutions to real-life problems. When your house leaks, you can fix it yourself. If the owners of an apartment block are willing to rebuild it they can do so, but some problems require starting afresh on a big scale."

Aside from the fact that the houses in Mingtsui are old, its narrow lanes cause all sorts of problems. "Neighbors of 20 years standing often get into a free-for-all over a parking spot," says Hsu. Rows of motorcycles parked under street arcades, store closures, and motor-scooter-riding purse snatchers in dark alleys have become increasingly common of late.

The community's urban renewal project envisages more green areas and leisure facilities, as well as high-rise buildings that will house supermarkets, malls, and private businesses. After Hsu Wen-hung began to drum up support for his project among local residents last year, the price of apartments in 30-year-old four-story buildings began to rise. According to a local real estate broker, since the beginning of this year the going price for an old apartment has climbed from NT$110,000 to NT$170,000 per ping.

Houses no one wanted to buy until recently have suddenly attracted keen interest among potential buyers. Major real estate developers have smelled an opportunity to make big bucks and are swarming in. The most energetic player is Taiwan Development Corporation (TDC), which in recent years has transformed itself into company that specializes in urban renewal. Although it has not yet signed a formal contract, TDC has sent a special task force to Tokyo to learn what it can from Roppongi Hills, Japan's most famous urban renewal project, in the hope that it will be able to apply these lessons to the redevelopment of Mingtsui.

"The recent allegations about TDC have affected the views of many locals," admits Hsu Wen-hung, who is working hard to win over residents, 10% of whom must approve the project for it to be approved.

Unexpected problems can arise just when the light at the end of the tunnel appears. The case of Mingtsui Borough illustrates that time is not always on the investors' side; to housing developers it may simply be a synonym for risk.

Advanced building methods and technology have reduced construction times but communication and negotiations can drag on indefinitely. The projected cost of renewal on this six-hectare site has reached NT$200 million. In addition, there are tangible and intangible costs arising from negotiations with residents, as well as alarmingly high costs for preparatory work.

"The longer time drags on, the higher the risk. Long and tedious discussions make it impossible for developers to predict when they will recoup their investment." Gradual real estate saturation in the greater Taipei area has made it increasingly difficult to find land for new building projects. Chien Po-yin of Sheng Yang Real Estate has set a two-year time limit for the completion of all development projects his company undertakes: "There aren't many companies in our business with the financial resources to stubbornly press ahead with a major and complex project such as Mingtsui."

"As soon as they hear the term 'urban renewal,' people imagine another Roppongi Hills, the Tokyo landmark," says Chang Chin-oh. "We envy the remarkable success of Roppongi Hills but we aren't willing to learn from that project." The Mori Building Group in Tokyo spent more than 15 years lobbying residents to approve the project, negotiating the terms of the contract, completing the construction work, and attracting business. "It takes time to get an inch of gold for an inch of land," concludes Chang.

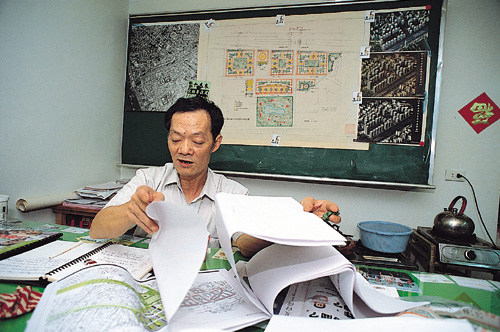

When the Mingtsui Borough project hit the headlines, all sorts of proposals started pouring, which now cover the walls and desk of borough warden Hsu Wen-hung (right). But this old community, which is located near the MRT and the East-West Expressway, still has a long way to go to transform itself.

The human factor

Metropolises in the Asia-Pacific region are the world's fastest-growing cities. Cities with a million or more inhabitants in Japan, South Korea and mainland China are experiencing a boom of the new superseding the old. As demand grows for refashioned urban environments, city after city is touting its urban renewal schemes. Besides Roppongi Hills, other much talked about urban renewal projects are the Marunouchi and Yokohama MM21 projects in Japan, the Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project in Seoul, and the Xintiandi project in Shanghai.

There are currently seven urban renewal sites in Taipei City, including the Construction and Planning Administration's Huakuang Community project, a 12-hectare site in a prime location next to the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall and the adjacent land belonging to Chunghwa Telecom and Chunghwa Post.

Although the above-named government and private consortium-led big-ticket projects have been remarkably successful, governments around the world hope that residents themselves will be able to play a leading role in large-scale residential urban renewal projects. "The crux is that the government lacks sufficient personnel and financial resources to support every single residential redevelopment project," says Pien Tyzz-shuh.

Of the four government-run urban development projects in Taipei City, three are concentrated on the old district along Kuisui Street. "It's bad enough that the houses in this area are old and run down. Even more importantly, we can't allow the urban development gap to widen any further, because once some areas hit the skids it becomes much harder to revitalize them," says Pien.

In Europe and America, unbalanced urban development has caused all sorts of very visible problems. In his well-known book The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy, the British sociologist Anthony Giddens explores the problem of "crime and community" at some length. Giddens writes that what most concerns residents of troubled neighborhoods in European and American cities are abandoned cars, graffiti, and youth gangs. As soon as these problems emerge, people "leave the areas in question if they can, or they buy heavy locks for their doors and bars for their windows, and abandon public facilities.... Fearful citizens stay off the streets, avoid certain neighbourhoods, and curtail their normal activities and associations."

To meet such challenges, "the answer may well be for Taiwan to pursue integrated community development for a decade or two," says Chang Chin-oh. Although Taiwan's community development initiatives have only had an impact in a limited number of rural areas, Chang thinks they could be tried in cities: "Community organizations and apartment-building management committees can play a role in this. Team reeducation could spur a bottom-up process of community regeneration."

"But I feel that most people's thinking is not going deep enough. An urban environment grows organically over many years. You can't focus first on goals and interests and then build an urban environment. These are two different processes. That is what is valuable about the Mingtsui and Prosperity Residences projects," says Chang.

When the Mingtsui Borough project hit the headlines, all sorts of proposals started pouring, which now cover the walls and desk of borough warden Hsu Wen-hung (right). But this old community, which is located near the MRT and the East-West Expressway, still has a long way to go to transform itself.

Looking to the future

Japan's Roppongi Hills is a case in point. Quite apart from the many years of dialogue that preceded the project, what sets Roppongi Hills apart from many urban renewal projects around the world, including Taiwan's, is that none of the more than 500 owners involved sold their land to Mori Building Group for speculative profit. All owners are still living in the Roppongi Hills Town site. They have signed lease agreements with Roppongi Hills and are now investors in the project.

"That's exactly what I proposed: that the Prosperity Residences project ought to be a company." At the public hearing, Billy Wang proposed his ambitious plan for a single-project company to his neighbors, most of whom had just wanted a new house. "The owners' equity share in the company is based on their real estate holdings. Decisions about the future direction of the project are made by a board of directors."

"This method is tantamount to an asset securitization of Prosperity Residences," says TDC's vice director Lin Chih-hsiang. "But the original aim of asset securitization was to discourage investors from pursuing short-term trading and to encourage them to make long-term investments. At the same time, a separation of property rights and managerial authority makes it possible to hire external professional management teams."

The core concept of this model for community building is that communities manage their own affairs through the participation of residents who exercise equity rights. Because the government cannot look after the owners and the market is unreliable, when problems arise it is up to the residents--the owners--themselves to find solutions. They must discuss issues of common concern to the community, make good use of outside professionals, and mount an effective defense against real estate developers and "integrated management policies" imposed from above by the government.

"We used to think, who'd want to buy such ugly houses?" says Chang Chin-oh. "Then people began to realize that urban renewal would at least give residents a large measure of decision-making power. Although there is no experience with such single-project companies, they can set a precedent that will show people that quite apart from obtaining a higher sale price and better terms in urban renewal projects, it is possible to revitalize communities and genuinely improve their quality of life."

Cramped living conditions force residents to keep cooking equipment and gas cans in the courtyard and corridors of Prosperity Residences.

Rebuilding trust

In The Third Way, Anthony Giddens writes, "'Community' doesn't imply trying to recapture lost forms of local solidarity; it refers to practical means of furthering the social and material refurbishment of neighbourhoods, towns and larger local areas."

"Joint venture projects initiated by housing developers which I assisted in the past often got stuck when one or other landlord demanded an exorbitant sum of money," says Chen Li-wen, an attorney for Omniservice Law Offices. "Although under the Urban Renewal Act urban renewal projects must be approved by two thirds of owners, when a resident refuses to grant his approval, his ownership rights can be transferred, which is tantamount to forcing him to agree. But I have yet to see an actual example of this."

Chen Li-wen notes that earlier this year, the US Supreme Court ruled that in the interest of economic development local governments may force private home owners and businesses to sell, provided they are given fair compensation. Given that most American cities want to promote urban renewal projects in poor neighborhoods, this ruling is expected to have a far-reaching impact.

"There is judicial precedent overseas and legislation in Taiwan, but in a society that prizes harmony as much as ours, how many people are really going to go down that road? I very much doubt that they will," says Chen.

What government policy and market forces cannot accomplish must be done by ordinary citizens. "If local residents don't trust me, I'm afraid that we won't accomplish anything despite floor space incentives, tax reductions, 'rights conversions' and other preferential policies," says Hsu Wen-hung, who has parried attacks from TDC and recently won a fiercely contested borough warden election. Although he was initially full of confidence in the Mingtsui urban renewal project, he now feels it to be an unbearable weight on his shoulders.

Just to complicate matters, back in downtown Taipei, the city government has once again become a co-owner of Prosperity Residences, which was originally built to house families who had been relocated to make way for the railroads. Urban renewal regulations stipulate that publicly owned land within an urban renewal zone may be bought from the government at market prices by private titleholders within the zone, but public authorities are jittery because in recent years sales of public property have been criticized at every turn.

As an outsider to the community, Chen Li-wen asks, "Who can play the role of an impartial mediator between housing developers and residents? Someone who can bring professional expertise to evaluation and fiduciary questions and is willing to put in the time to talk with each side?"

Chang Chin-oh minces no words: "In the final analysis it's a question of trust. In a society in which people don't trust each other anyone who comes forward with a renewal project is always going to be initially regarded with suspicion. And that is tragic for society."

It's a complicated business. No matter how closely one investigates fluctuating real estate prices and factors beyond the power of legislation to regulate, in the end it always comes down to people--that is, to human relations.

The success or failure of urban development should be viewed in this light.

Though located in a prime downtown area near Taipei 101 (facing page), Prosperity Residences is gradually falling into disrepair, as this furred-up pipe illustrates all too well.