A China Airlines TV advert with an attentively smiling hostess and the caption "Fate brings people together" has caught many viewers' attention. Indeed, for the Chinese, the word "fate" is no stranger.

The Chinese not only speak of fate in the bonds between husband and wife or parents and children, in making friends or seeing employment; even those areas of life requiring rational consideration such as buying a house, investing in stocks and shares or purchasing furniture and household appliances may involve some element of "fate."

So just what is "fate"?

"Stories of the Tang" includes the following tale: A young man by the name of Wei Ku had long searched in vain for a suitable marriage partner.One day he came to Sungcheng, where he met an old man sitting on the steps in front of a temple. As they chatted, the old man told him that people's marriage fate is predestined, and the two partners are bound together by an invisible red thread. Curious, Wei Ku asked the old man to tell him who was the wife which fate had chosen for him.

The old man led Wei Ku away to the north of an inn, and pointing to a two-year-old baby girl in the arms of an old woman who was selling vegetables, told him: "That is your wife to be. She is destined to become very rich, and if you marry her you will surely rise high in the world." But Wei Ku had always wanted to marry a wife from a noble family, and could not bear the thought of marrying a pauper, so he sent a servant to stab the baby girl to death. However, the servant missed his stroke and failed to kill her, only leaving a cut between the girl's eyebrows.

Fourteen years later, Wei Ku's dream was fulfilled when he married the daughter of the provincial governor. But he was surprised to find that his wife always wore a paper flower stuck between her eyebrows. At his persistent questioning, his wife tearfully told him: "My parents spent many years as officials in other provinces, and so as a little girl I was left to be raised in my wet-nurse's family. But when I was two years old I was injured by a young ruffian who burst into my nurse's house, and ever since that day I have borne an indelible scar between my eyebrows."

For his wife was the very same two-year-old baby girl which his servant had failed to kill all those years ago. When the governor of Sungcheng heard of this affair, he had the inn at which Wei Ku had stayed renamed "Betrothal Inn."

In olden days, people believed that "marriages are made in heaven." But what about today in 20th Century Taipei? What do city boys and girls with a modern education think about "marriage fate"?

Novelist Chang Man-chuen, who is steeped in the study of classical literature and makes a profession of writing modern fiction, can give full rein to her romanticism through the characters which she creates, but in real life is faced with the regret that "fate hasn't done its work yet." She says: "Marriage is something for two people. If that Mr. or Miss "Right" hasn't come along, then however hard you try you will get nowhere. After all, as we Chinese say, if your partner isn't right you won't get along!"

"Fate hasn't done its work" is the explanation used again and again by people who have reached marriageable age but who show no signs of getting hitched, when asked about the future. In their paper The Role of Yuan in Chinese Social Life: a Conceptual and Empirical Analysis, published in 1988, Professor Yang Kuo-shu of National Taiwan University's Department of Psychology and Professor David Ho of Hong Kong University's Department of Psychology analyze 1008 songs from 92 albums in the Hong Kong commercial media's hit parades for the four years from 1980 to 1984. These songs include 91 (9%) in whose text the word yuan ('fate') appears; and in these 91 songs yuan appears in 122 lyrical expressions.

Many people in Chinese society understand the magic of "fate."

"Fate" originally meant cause and effect:

Chinese history does not reveal when the idea of fate first originated. The earliest written records date from the Tang Dynasty, when Buddhism spread eastward from India. The word yuan [which in modern Chinese means "bonds of fate or predestiny"] appears in the phrase yuan ch'i hsing k'ung, which expresses the Indian Buddhist view that "the chain of dependent origination [pratitya-samutpada, the dynamic structure of samsara, the Round of birth-and-death] is inherently void," which means that all events and things arise from external conditions, and that the self-nature [svabhava] of all existence in this world is void and has no reality. When external conditions disappear, then the world and self disappear with them.

Thus yuan as referred to in Indian Buddhism is something brief and transitory. The causal cycle of creation and destruction repeats itself from moment to moment.

"The Buddhist view of dependent origination aims to release us from our attachment to the world, to self, to fame and fortune, to love and to all emotions, for the inability to let go of these brings vexation and suffering," observes Professor Wang Pang-hsiung of Central University's Department of Philosophy.

Thus fate in Buddhism refers to action resulting from outer circumstances and to acting in accordance with one's situation. People have to exist in the world of an unceasing cycle of creation and destruction, and it is only if one understands how to "go with life's flow," to face the illusory nature of human life, to be at peace with whatever fortune brings, and neither to hold tight nor cast away, that one can be contented in this inconstant world.

But this does not mean that one can only passively await good fortune and endure misfortune, for fate in popular Chinese thinking leaves scope for human effort. Thus good deeds can break down ill fortune, and by acting virtuously at every opportunity one may create good fortune.

This is the original meaning of fate.

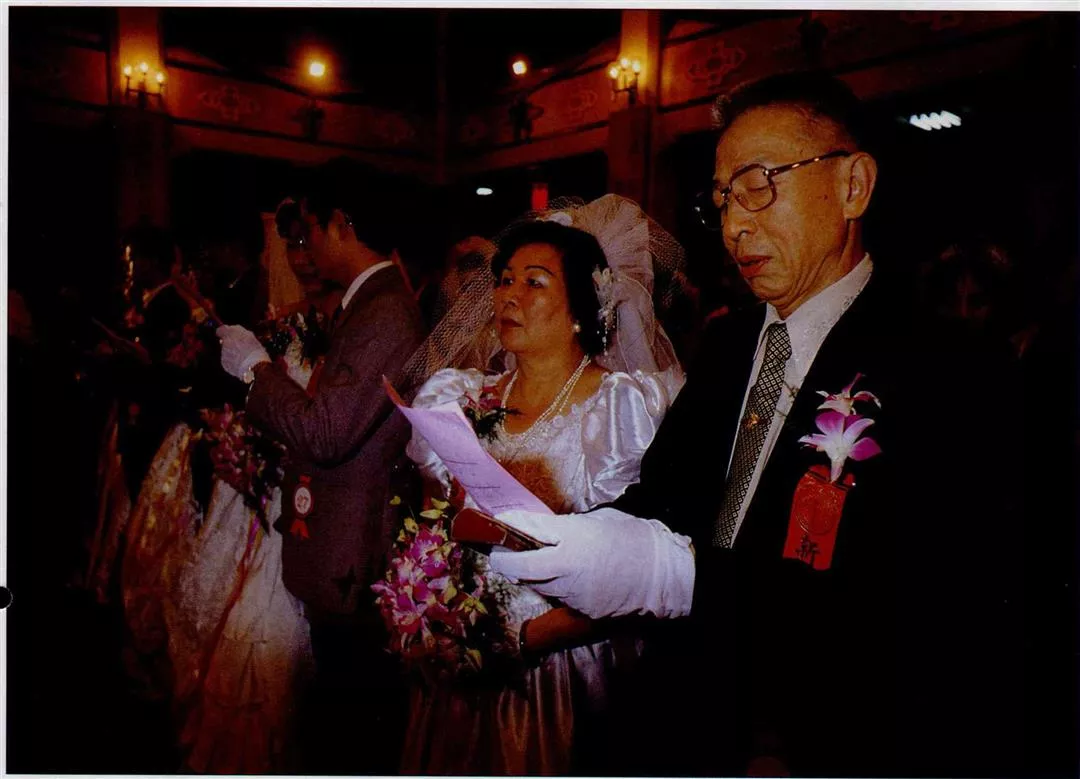

Though fate has waited long to bring these lovers together, they will no t let their destiny pass them by.

Only one's allotted destiny brings permanence:

But the Chinese have transferred the notion of fate to human relationships, and the fate or allotted destiny of which they speak today fits in perfectly with the philosophical viewpoint of Chinese Confucianism. In Professor Wang Pang-hsiung's view, the spirit of Chinese culture stresses permanence, and people find unsettling the Buddhists' causal fate of fleeting birth and death, illusion and emptiness. Thus by making fate "allotted", they tie it down and give it permanence.

In this way, fate evolved from the Buddhists' fleeting cycle of change to a thoroughly Chinese notion of permanence.

In Chinese thinking, that which is "allotted" includes not only the innate fortune expressed in the eight characters denoting the date and hour of one's birth, but also the acquired system of values shaped by one's family and background. Thus when fate brings people together but does not bind them, or fails to "do its work," it offends against Chinese people's desire for the enduring and for lifelong relationships, and produces a sense of regret and tragedy.

Between joy when fate brings people together and impotence in the face of the fate which parts them, how can one arrive at a good or benign fate which can interpret the mysterious code of another's fortune and bring congeniality of aspirations and interests, harmony of temperaments, and mutual understanding? This is a lesson which the Chinese have been striving to learn since ancient times.

I don't know who owes whom the greater debt from our past lives, but sit ting on your shoulders I can see the broad sky and the wide ocean.

Fate and Chinese literature:

Looking back at Chinese history, the use of the concept of "fate" reached its peak in the literature of the Ming and Ching Dynasties, when "many novels even put the word 'fate' right into their titles, such as Fate of Gold and Jade, Fate of the Reborn, Plum Joy Fate, Tales of Marriage Fate to Awaken the World and A Tale of Strange Fate in the Chou Li Garden," observes Professor Yang Kuo-shu of Taiwan University's Psychology Department.

Apart from "fate", appearing directly in books' titles. when the heroes and heroines of Chinese classical literature first meet, often the earth shakes and the sky spins, and it is as if they have lived their whole lives for this moment. For instance, in The West Chamber by Wang Shih-fu of the Yuan Dynasty, Chang Chun-jui falls in love with Tsui Ying-ying at first sight, as if stricken by the force of "500 years of illicit desire." And when Mu Li-niang, heroine of The Peony Pavilion by Tang Hsien-tsu of the Ching Dynasty, sees the hero Lui Meng-mei in a dream, she pines for him night and day until she finally dies of a broken heart. This develops the magical power of fate to even greater heights.

The context in which the Chinese refer to fate most often is love. This is also why Chinese people generally print their bright red wedding invitations which such congratulatory phrases as "Heaven sends good fortune," and "Fate decides one's whole life." At the end of last year, after a courtship of almost two years, Li Ching, who works in the Chinese section of the overseas service of the Broadcasting Corporation of China, married her colleague, Li Hsi-chiang of the Thai section. Their wedding invitations were printed with the phrase "A single thread draws those fated to marry together across a thousand li." And to make it fit the facts, Li Ching's mother had even considered changing "a thousand li" to "ten thousand li"!

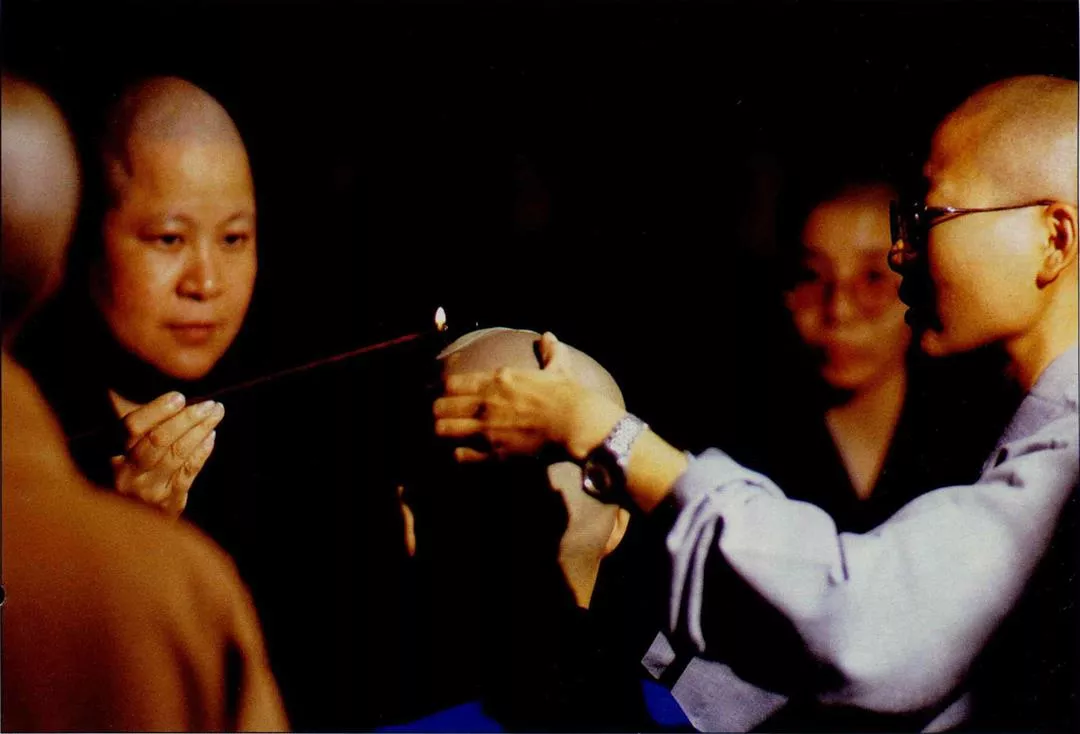

These scars will mark the end of her secular destiny and bind her life t o the Buddha. (photo by Vincent Chang)

A single thread across a thousand li:

There is no doubt that of all the kinds of fate. it is the fate that governs marriage which is most able to touch and soften people's hearts. "Those whom fate binds together will find each other though separated by a thousand li; those whom fate does not bind will not know each other though standing face to face"; "A single thread draws those fated to marry together across a thousand li"; "Marriages are made in heaven," and so on are all heartfelt words of congratulation for lovers able to have the good fortune to meet, the heart to understand each other, the feelings to love each other and finally the destiny to spend their lives together.

According to legend, the fate which governs marriage is controlled by the book of marriage fate in the hands of the Old Man Under the Moon, who uses the red silken thread in his pocket to firmly link the feet of boys and girls destined to become husband and wife, so that they may one day meet. This further adds a sense of beauty to the fate governing marriage.

Professor Yang Kuo-shu observes that there is no clear biological process which can explain the mutual attraction or rejection between marriage partners or friends of opposite sexes, and so fate becomes the most satisfactory explanation for those mysterious states of the soul.

"Perhaps it is the indistinct nature of the concept of fate which makes it so applicable to people's everyday lives, which drift around the edges of the nets and structures of norms, without the severity and precision of Western civilization. Thus many life experiences, whether joyful or tragic, become acceptable when explained as fate. The people involved get an immediate spiritual release, and can face life once again." This is how Professor Yeh Chi-cheng of Taiwan University's Sociology Department analyzes the way "fate", plays a "consoling" role in the lives of ordinary Chinese. And for this process to take effect, "one does not need empirical evidence, one need only believe."

Everything is determined by fate:

Chinese people apply the concept of fate not only to love, but to all relationships between people, including the blood fate which binds one to parents and relatives, the marriage fate between husband and wife, the fate of friendship which ties friends together, and even the "Buddha fate" and the bonds of fate between the living and the dead which link humans to the world beyond. In other words, for the Chinese, fate is a kind of pre-allotted or predetermined human relationship.

Professor Li Pei-liang of Hong Kong Chinese University's Sociology Department has said: "In the minds of many Hong Kong Chinese, the concept of fate is a completely natural one, which they apply in understanding the relationships between all things and events."

Apart from the bonds of fate between people, the concept of fate may also be applied to things or events. When applied to things, it refers to the relationships between people and physical objects such as antiques, household furniture, small animals like cats and dogs, and so on. When applied to events or activities, it refers to the relationship between people and events, such as investment in stocks, employment and so forth.

In a nutshell, the concept of fate in Chinese people's everyday lives provides a simple reason which can explain the meeting and parting, joining and separation, attraction or rejection between all things.

This attitude of ascribing everything to fate could be described as "pan-fatalism." If somebody loves to read books, we say they have "book fate"; if somebody loves watching theater or is good at acting we say they have "theater fate"; a person who collects teapots we say has "teapot fate"; and if somebody is particularly photogenic we say they have "lens fate" ....

Professor Yang Kuo-shu observes that using fate to explain the harmonious relationships between people and things and events of all kinds is simply a way of describing an ineffable state of congeniality. "It is as if things which one could not explain in a whole day, if one just calls them fate, it is enough to reach a common intuitive understanding."

Professor Yeh Chi-cheng of Taiwan University's Sociology Department believes that for Chinese people, fate is a system for explaining human beings' relationship with the universe, and allows one to glimpse a special facet of Chinese culture: humanity's position is one of co-existence with and tolerance of nature, and not of one-sided subjugation and possession.

Better no fate than ill fate:

Of course, fate as understood by the Chinese is not confined to harmonious and happy interactions, but also includes relationships of conflict and suffering. Long term, permanent bonds of fate between relatives such as father and son, or the fleeting, chance relation ships of brief encounters with strangers may all be governed by a satisfying, kindly fate or equally by tragic ill fortune. Miss Chen, who works at the Taipei Life Insurance Association, feels that there is no bond of fate between her and her mother, because her mother constantly enumerates her faults in front of friends and family. She says that "for me the feeling that 'mother and daughter's hearts are linked' is something unattainable."

The Chinese have a saying that "It takes 10 years [of cultivation in past lives] to [create the bonds of fate to] cross a river in the same boat with someone, and 100 years to share the same pillow for life." But though fate may destine people to meet or even to marry this does not guarantee that it is a good or kind fate. When devoted sweethearts whom love's marathon has brought to the altar make their vows among the good wishes of friends and relations, this does not mean that henceforth they will live happily ever after like a prince and princess in a fairy tale. In fact there are many seemingly well-matched couples who do not pass life's rough test, and whose marriages become unhappy ones.

Seen in this way, from the process of meeting and separation one can only say whether or not fate links two people together. But to know whether the fate which links them is good or bad, one must see whether their final relationship is harmonious. Thus the concept of fate only governs people's meetings with things and events, but whether the relationship that develops after such a meeting brings fulfillment or disappointment all depends on a person's own efforts. This is the meaning of the expression "the teacher can point the way, but the path each person follows is his own."

Fate as an "attributional process":

Why is fate so important in Chinese society?

In his Fate and its Role in Modern life, Professor Yang Kuo-shu points out that since ancient times, China has been a country based on agriculture, and that the agrarian lifestyle requires large amounts of time and manpower and a stable social structure; this prompted the development of Chinese-style collectivism centered on the family clan. Within the clan, individuals strive to maintain solidarity and harmony among its members, and they care about others' opinions about themselves. And fate plays an effective role in maintaining harmonious human relationships.

Looked at from the standpoint of social psychology, ascribing the existence or absence and the quality of human relationships to an external factor--fate, with its connotations of predetermination--is nothing other than a process of attribution, in which responsibility for all meetings and partings between people is laid at fate's door. This attributional process not only has the effect of protecting oneself and others, but also enables people to better tolerate existing circumstances, and maintains the stability of the clan and of human relationships. This was essential in enabling the members of agricultural society to accept its rigid social structure without complaint.

In other words, when human relationships succeed or fail, invoking fate is an effective method of protecting oneself and society. Traditionally, the Chinese prefer to attribute harmony in their relationships to good fate rather than to good character or actions. For instance, by ascribing a happy marriage, paternal benevolence or filial piety to fate, one may avoid arousing self-reproach or envy in unhappily married couples or unfilial children, which might destroy harmony; by doing so one can also display modesty and thus earn social approval.

A lucky doctor treats you when you're getting well:

How does this apparently fuzzy concept of "fate," which nevertheless is deeply rooted in Chinese culture, affect people's actions? Under the influence of fate, do individuals feel that their own position is completely passive?

In his Social Science and Local Consciousness, as Evidenced by the Role of Fate in Medicine, Professor Li Pei-liang analyzes how belief in fate in regard to medicine affects how people seek treatment.

His research shows that belief in the role of fate in medicine increases patients' propensity to switch doctors. Many people believe that doctors and patients must by linked by bonds of predestiny for treatment to be effective. Thus when patients seek treatment, apart from considering the level of a doctor's skill, they will also consider whether they and the doctor are linked by fate. Swift recovery shows that such links exist; a slow recovery shows that no link of fate exists, and the patient will seek another doctor. For those who believe in fate in medicine, changing doctors is a rational act which assists treatment and recovery.

Thus Hong Kong Chinese have a saying that "a lucky doctor treats patients who are getting well." This saying reflects how widespread the practice of changing doctors is.

"Going with the flow" brings contentment:

Whether or not there is really a pair of invisible hands controlling our relationships, people still place their hope in the action of fate. Someone has said: "Fate cannot work without desire. and only when one cherishes fate will it bring fulfillment." Through the joys and sorrows, partings and reunions which life brings, and which one can neither predict nor control, perhaps to cherish them is the best footnote one can give to each period of life fate brings.

Faced with each of the joys and tribulations of human existence, and the inexplicable pattern of life, by simply sighing, "It must be fate!" one can pick up the pieces of one's own emotions and be ready to face the next day. It seems that deep in their souls, Chinese people have forged inextricable links with fate. After all, by accepting fate one can remain contented whatever it brings.

[Picture Caption]

p.27

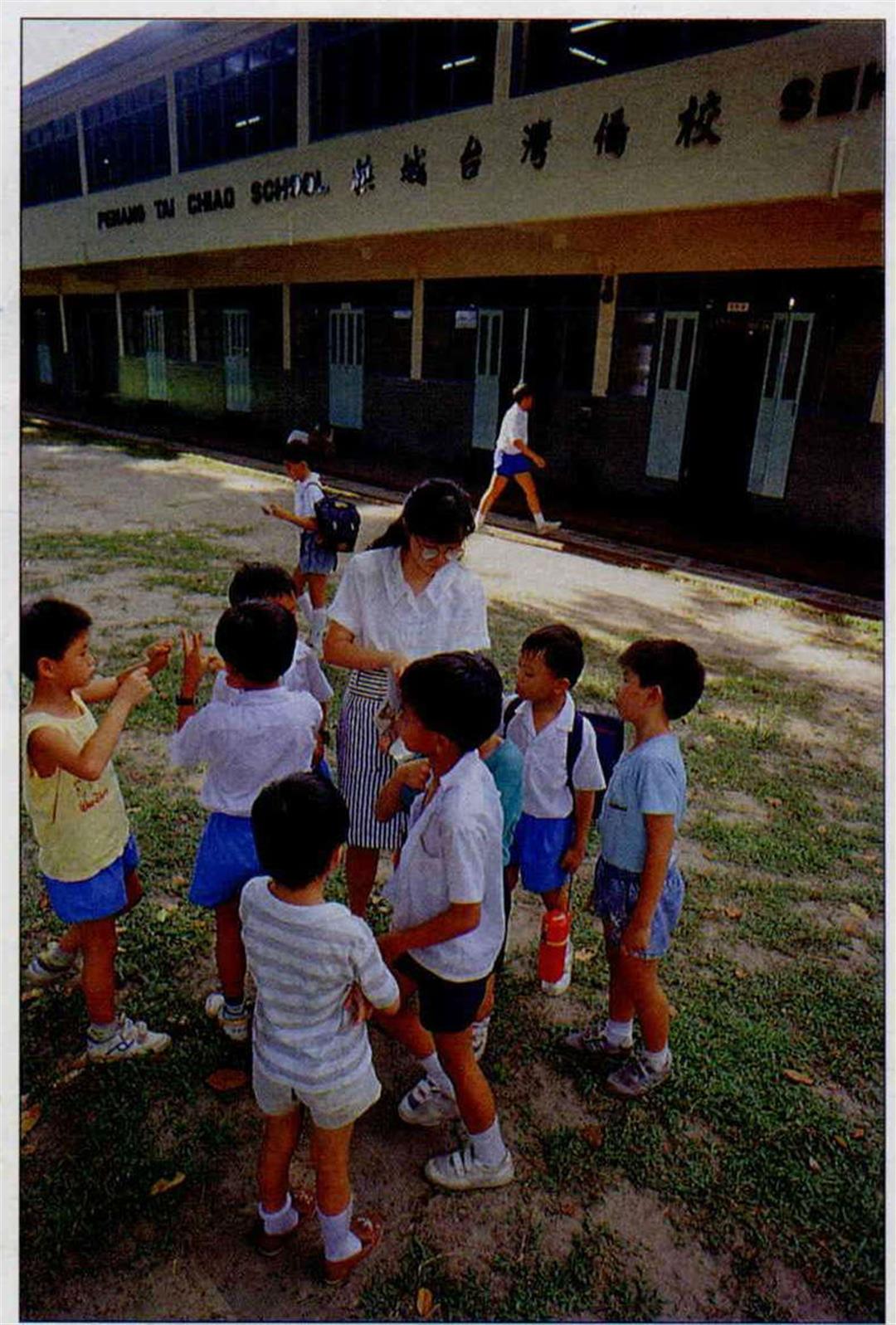

Though fate has waited long to bring these lovers together, they will not let their destiny pass them by.

p.28

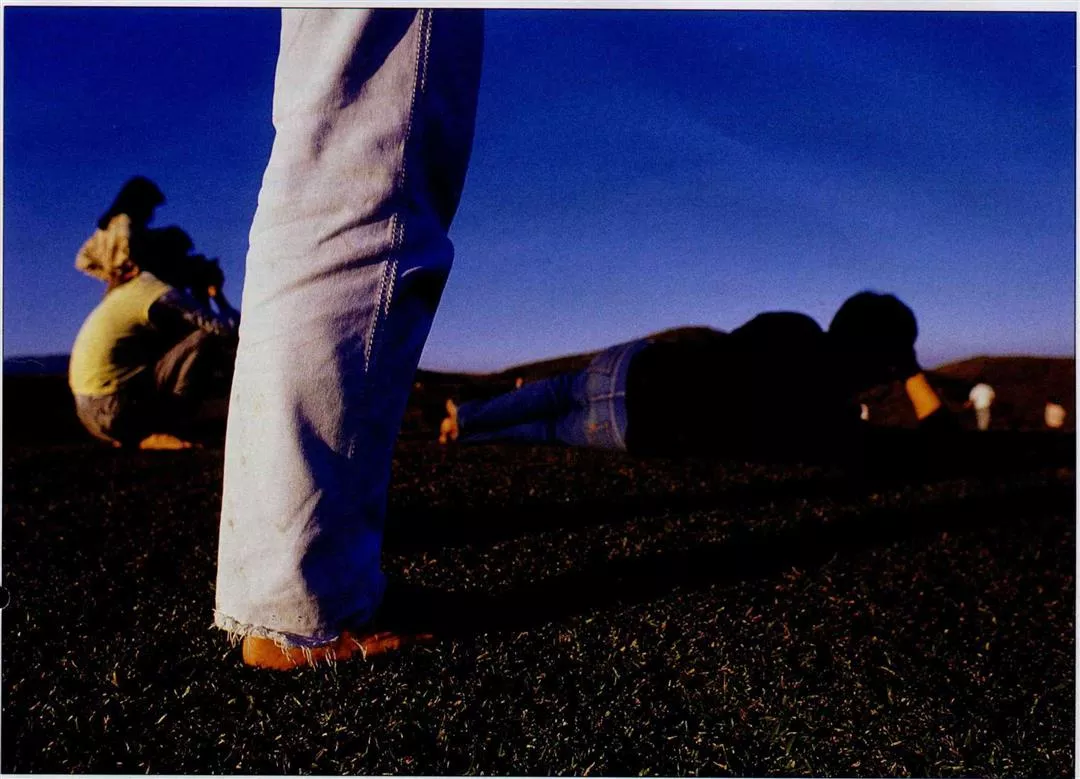

I don't know who owes whom the greater debt from our past lives, but sitting on your shoulders I can see the broad sky and the wide ocean.

p.31

These scars will mark the end of her secular destiny and bind her life t o the Buddha. (photo by Vincent Chang)

p.32

Although we are fated to cross in the same boat, if there is no spark between us when we meet, then once we reach the other shore you will go your way and I mine.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)