The Presidential Palace Opens Its Doors

Jenny Hu / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Robert Taylor

December 1994

The Presidential Palace is a symbol of the Republic of China's highest level of national leadership. Though the palace stands tall in a central position in downtown Taipei with countless people and vehicles streaming along the wide roads on all sides, the heavy guard of military police all around it has long made it an unapproachable, sternly mysterious forbidden territory in the eyes of the public.

Counting from when work on it began, this great building is the same age as the ROC itself. It has seen the Japanese occupation and such political changes as Taiwan's return to Chinese rule, the ROC government's relocation to Taiwan, and martial law and its lifting. It has housed eleven Japanese governors-general and--to date--four presidents of the Republic of China. Throughout the upheavals of history, this place has always been the center of political power in Taiwan.

On 2 January 1995, some rooms of the Presidential Palace will be opened for public viewing. What face is hidden behind the palace's veil of mystery? And what stories can it tell?

In April 1994, when the Legislative Yuan's organic law and statutes committee and budget committee reviewed the budget for the Office of the President, they appended a resolution suggesting that the Presidential Palace should be opened to public visiting. In mid-July, presidential spokesman Raymond R.M. Tai formally replied that starting in 1995, the palace would be opened to the public twice a year: on 2 January (a national holiday), and on one Sunday in August.

In fact, the public has been admitted to the Presidential Palace before. In 1958 well-wishers were allowed into its lobby to sign their names in honor of President Chiang Kai-shek's birthday. After Chiang's death, from 1975 to 1991 the public was also admitted each year on 31 October--Chiang Kai-shek's birthday--to remember the late President by bowing in front of his statue. But following the great changes in the political climate within the ROC in recent years, this practice was discontinued in 1992. According to statistics, over 20,000 members of the public entered the Presidential Palace each year.

Although the palace's impending opening is not the first, it does have a special significance. In the past, when the public entered the building it was to show their respect for a "leader." After entering through the main front doorway, they would sign their names and bow before the bronze statue of President Chiang, then immediately pass through the central lobby and leave through the main rear door (popularly known as the "Great West Door"). This brief transit took no more than five minutes. But this time the famous branching staircase which leads to the third floor will no longer be off limits, so the public will at last have the chance to enter Chiang Kai-shek's former office, the president's reception room, and "Chiehshou Hall," the venue for important ceremonial occasions.

"The Presidential Palace is not like the White House in the USA, which is also a residence, and whose rooms and courtyards have been embellished by its masters down the years. This is purely a place of work," says Raymond Tai. Because there really is not that much to see within the building, the Office of the President decided only to open those of the grander rooms where security would not be serious concern. For the time being the current president's and vice president's offices will not be open.

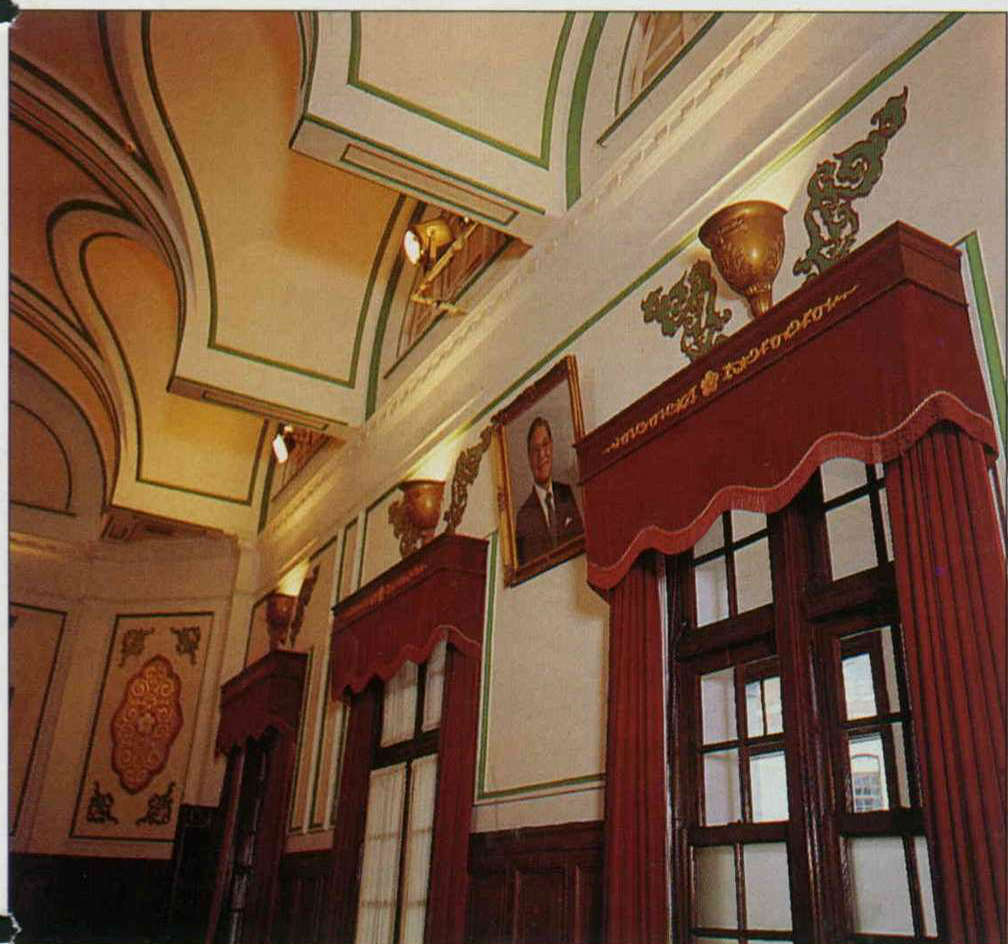

Over the last 80 years, the entire internal and external layout of this Japanese-occupation building has remained unchanged. Seeing the sunlight streaming in from the courtyard, casting the pattern of the long rows of windows into its quiet and lonely red-carpeted corridors, one feels a trance-like sense of historical space and time welling up irresistibly inside one.

Eighty years ago, nothing stood on this three and-a-half-hectare site in the center of old Taipei at the crossroads of North Gate Street (now Yenping North Road), East Gate Street (Jen-ai Road and Hsinyi Road), South Gate Street (Nanchang Road) and West Gate Street (Changsha Street)--except the ancestral shrines of the Lin and Chen clans. All around there were only open fields.

Throughout the first decade of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, the Governor-General's Office was temporarily housed in the former offices of the Ching dynasty civil and financial administrator for Taiwan (this structure was located close to the present site of the Taipei City police headquarters and Chungshan Hall; it was demolished in 1931 and parts of it reerected in the Botanical Gardens, where they are now classed as a Class 2 national monument). At that time armed popular resistance groups were still intermittently active and threatened the power and authority of the colonial rulers. Thus the senior civil administrator Goto Shinpei suggested to the fourth governor-general, Kodama Gentaro, that because the offices were too small and unprepossessing, and "in order to sweep away the islanders' nostalgia for the Ching dynasty and give concrete expression to the prestige of the Empire... we must erect a majestic administration building, to show the permanence of our rule." This is the description given by Japanese historian Sugiyama Yasunori in his Achievements in Office of the Governors-General of Taiwan.

The suggestion was approved by the Japanese Diet, and in 1906 the first round of a competition, open only to architects from within Japanese imperial territory, was completed. In the second round, held the following year, no first prize was awarded. Instead, the design of the second prize winner Nagano Heiji was selected: a symmetrical five-storey building with a central tower symbolizing the power and authority of the Japanese emperor, laid out in the shape of the character "日" (meaning "sun") to represent the name "Japan."

To enhance both the status and the practical usefulness of the building, the original design was revised to raise the central tower from six storeys to nine storeys and expand the office space to accommodate 1000 people; the budget was also adjusted from ?1.5 million to ?2 million. "At that time, Japan's power was in the ascendancy and the Japanese planned to build up Taiwan as their main base from which they would push south into Southeast Asia. This imposing building was the symbol of this ambition," comments architect Li Chung-yao, now in his seventies, who worked as a technical officer in the Governor-General's Office during the Japanese occupation, and who has a deep knowledge of the building's origins. Architect Wu Kuang-ting, on the other hand, describes the shape of the building thus: "The wings to the right and left are like two massive epaulettes, while the central section is like a tall military cap, and the decorations on its facade resemble the braid on the cap."

After the site was chosen, the Chen family shrine was moved to Tataocheng and the Lin family shrine to the district to the north of the railway station, and engineers and materials began to arrive from Japan. Work began on 1 June 1912 and was finally completed in March 1919. Because the outbreak of World War I while the work was in progress caused prices to rise, the final cost of the project totalled ?2.8 million.

This renaissance-baroque building, which reflects the architectural style current in Japan's Meiji Restoration period, faces almost due east, symbolizing loyalty to Japan, the Land of the Rising Sun. Its scale, with a width of 120 meters and a tower 60 meters high, makes it the most imposing of the buildings constructed in Taiwan during the island's 50 years of Japanese rule. Even 20 years ago, before Taipei began to bristle with skyscrapers, this landmark could be seen from anywhere in the city.

Once completed, the Governor-General's Office building aroused mixed reactions. Many people thought the central lobby and the staircase were too large and the corridors too long, and some even suggested that the tower, which serves no practical purpose, should have been left off. But in Li Chung yao's view, the building has a number of admirable features:

Firstly, because the building faces east and catches the sun, the design includes arcaded outside walkways along the east, south and west sides to prevent the sunlight shining directly in through the windows; the north side has no such arcades. This design is very well suited to the building's " physical environment." Better yet, Nagano Heiji even had the idea of avoiding "secondary smoking," for he provided rooms on each floor at the four inside corners of the " 日" shape, as smoking rooms. This aspect of the design was rejected at one point during the review procedure, but later, because the rooms also had the function of strengthening the building and making it more resistant to earthquakes, they were retained. After the building was completed, what earned the most praise was its workmanship and materials. It is thanks to these that today, so many years later, the Presidential Palace more than ever conveys a solemn sense of history.

To make the building solid and lasting, the Japanese used steel reinforcing bars as thick as railway rails, and built the walls in natural stone and brick, giving the whole structure a fortress-like solidity. Although the American forces dropped 500 tons of bombs on the building in the latter stages of World War II, its basic structure remained unscathed. Even today, it is said, whenever any internal repairs are made or new equipment is installed in the building, just knocking holes in the walls is a big headache for the contractors.

Li Chung-yao, who took part in the work of restoring the Governor-General's Office after the air raids, recalls that in early 1945, when the Pacific war was raging and the allied forces began to bomb Taipei, the staff from the Governor-General's Office were dispersed into the suburbs. On 31 May allied bombs struck the Governor-General's Office. Although they only damaged an elevator to the left of the tower over the main entrance, a staircase and two offices, the fire they started raged for three days and nights and the building was gutted. The damage extended to more than 83% of the building's area, and close to 100 people died.

The Governor-General's Office, the symbol of colonial imperial might, had become a ruin, seemingly presaging Japan's imminent defeat. In 1947, after the ROC government had regained possession of Taiwan, the Taiwan Provincial Government's Bureau of Public Works began to restore the building according to the original plans, and work was completed the following year. "We cleared away 10,000 ox-carts of rubble, and had over 500 people working there every day," recalls Li Chung-yao.

After the change of regime, the building was renamed "Chiehshou Palace" in honor of President Chiang Kai-shek' s 60th birthday, and was made the office of the Political and Military Administrator for Southeast China. In 1950, after the ROC government withdrew to Taiwan, it became the Presidential Palace, which it has remained to this day, successively accommodating four presidents: Chiang Kai-shek, Yen Chia-kan, Chiang Ching-kuo and the present incumbent, Lee Teng-hui.

Today's Presidential Palace seems like a lonely island surrounded on all sides by roads: Chungking South Road and Po-ai Road run past its front and rear entrances, while its left and right wings are skirted by Paoching Road and Kuiyang Street. The main entrance faces into the end of the 10-lane Chiehshou Road. Some people have questioned whether this position, exposed on all sides, does not have unfavorable fengshui. But Chen Cheng-shen, an advisor in the office of the presidential spokesman who is well versed in the principles of geomancy, explains that as the center of national power, the Presidential Palace can repulse any evil influence which may approach along the road, while the four streets around the building express its communication with all parts of the land.

When vehicles approaching the Presidential Palace along Chiehshou Road reach Chungking South Road, they must follow the directions of the officers of squad 415 of Taipei City traffic police, and pedestrians passing in front of the building are not permitted to cross the line of military police standing guard outside, nor may they loiter or take photographs at will. One former pupil of Taipei First Girls' High School even had the experience of being forbidden to make sketches at the side of Chiehshou Road.

Compared with the strict security surrounding the Presidential Palace today, some old Taipei residents recall that as the Governor-General' s Office it had a more friendly atmosphere.

"In those days ordinary folk could go into the Governor-General's Office; you just had to tell the policeman at the entrance who you were going to see. But you couldn't go in there barefoot or in sandals, or wearing a singlet," says an old man in his eighties who lives near Hengyang Road, pulling the cigarette out of his mouth and pointing towards the Presidential Palace as he speaks.

Under the Japanese occupation there were no special restrictions in the area surrounding the Governor-General's Office, so in souvenir albums of the Taipei High School from the 1930s one can see group photos of the school's pupils taken on the steps outside the front of the building. But because many high-voltage electric power lines ran into the Governor-General's Office from all sides to power its modern equipment, for safety's sake it was strictly forbidden to fly kites in the area.

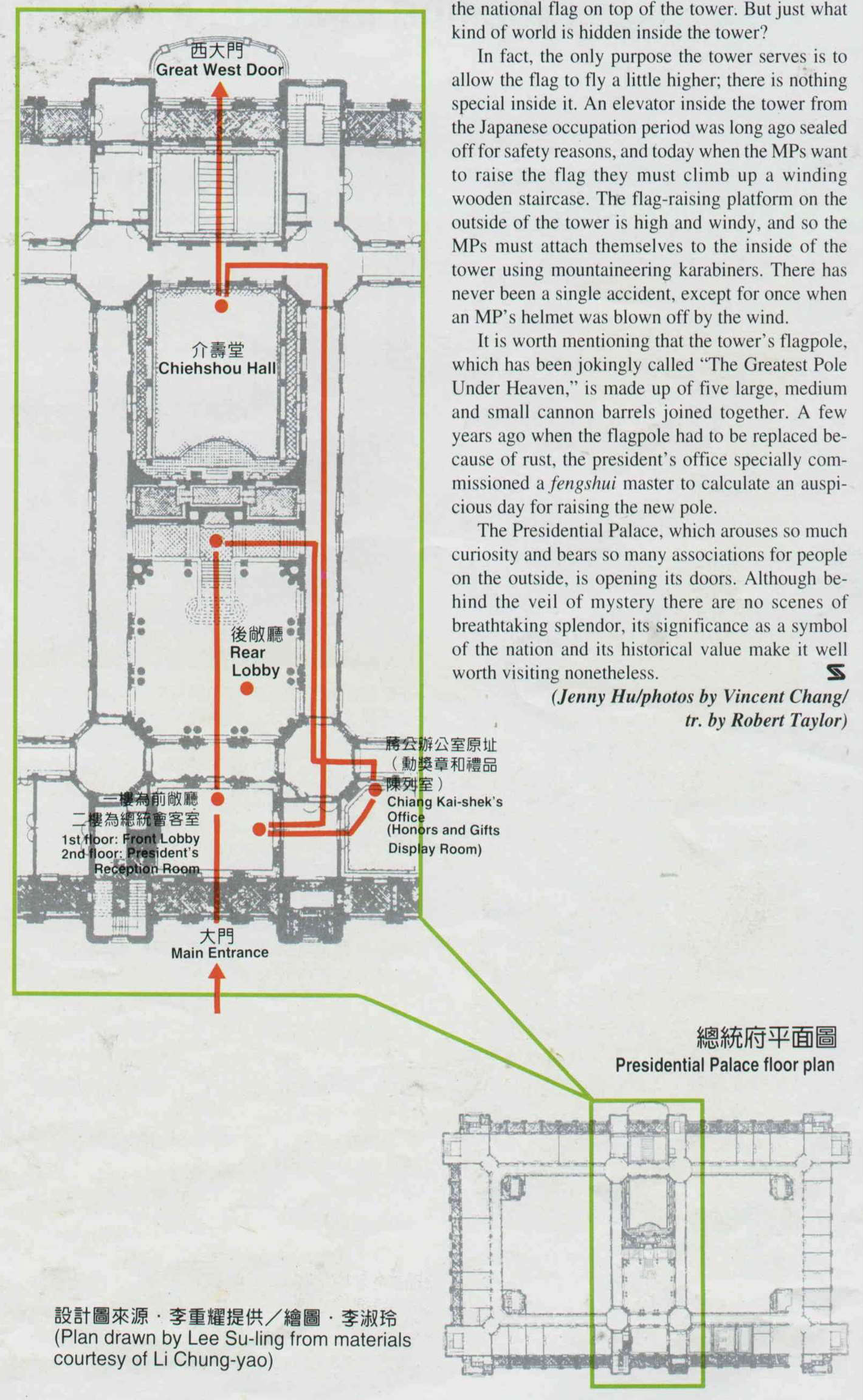

The Third Bureau at the Office of the President has already planned out the route which visitors will follow on 2 January. The public will enter through Gate 1 (near the junction of Chungking South Road and Paoching Road) and Gate 2 (near the junction of Chungking South Road and Kuiyang Street), and after passing through a simple security check, walk up the driveway and into the Presidential Palace through the main front entrance.

The first floor of the Presidential Palace forms its base, and walking up the driveway and steps to the main entrance one goes into the building on the second floor. According to the rules of protocol, the main entrance is normally reserved for the use of the president, the vice president and the president's guests of honor.

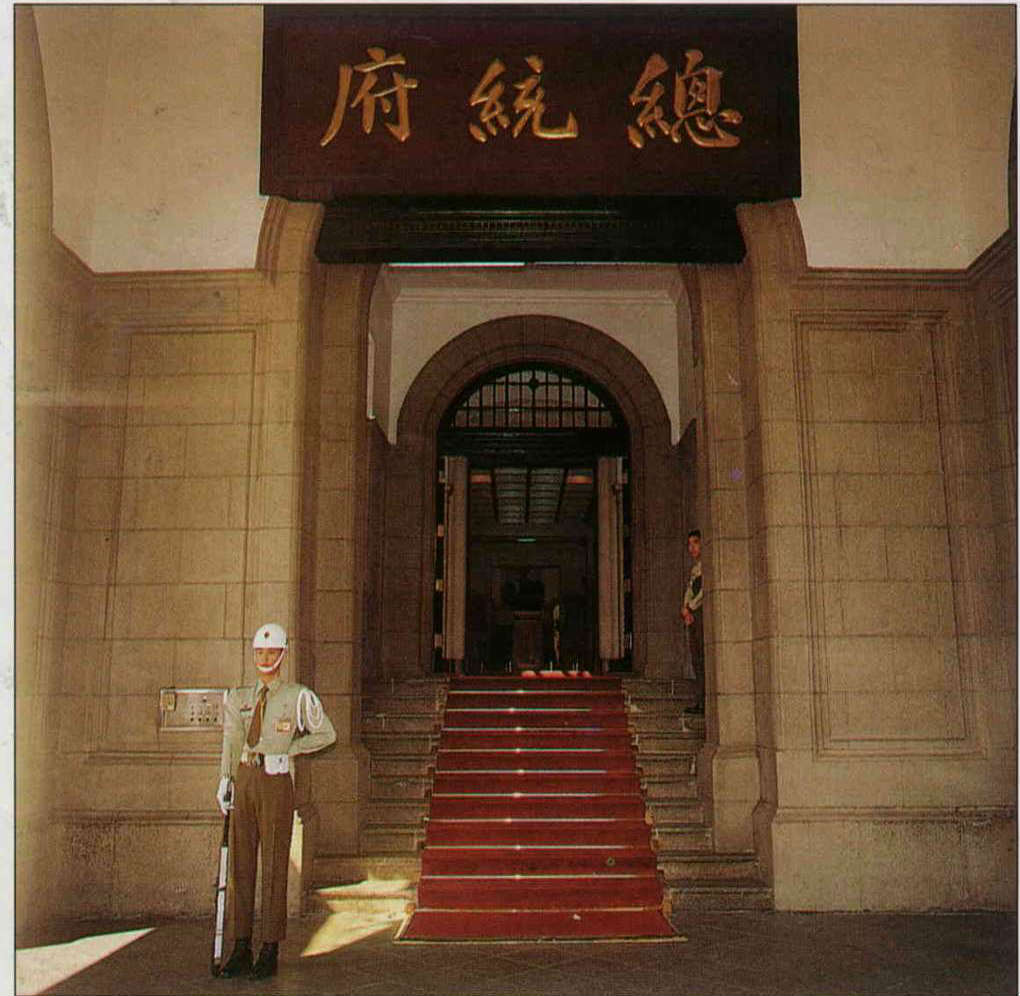

The porch spanning the driveway in front of the main entrance has electrically operated glass doors, and when a car carrying the president, vice president or their guests drives into the porch, these glass doors are automatically closed and are not opened again until the guests have alighted and entered the lobby. The two jet-black doors of the main entrance are planed and carved from two single pieces of Taiwan cypress. They are never closed, even when typhoons strike, to show that the Office of the President works all the year round. A plaque emblazoned with three large Chinese characters in regular script meaning "Office of the President" hangs high over the doorway, imparting a regal air.

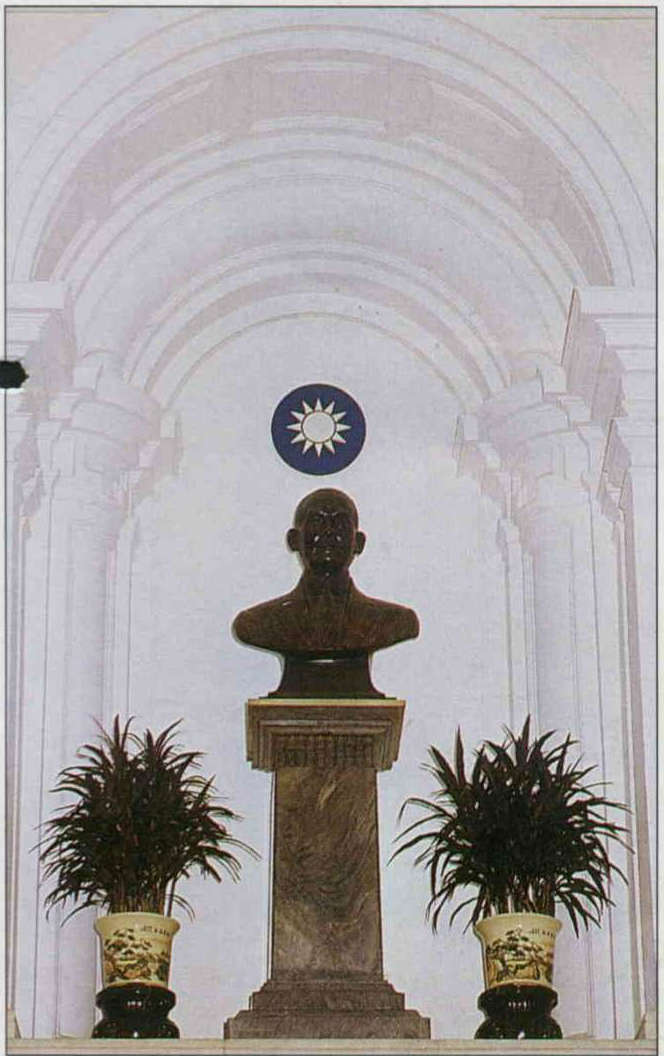

Passing through the main doorway and entering the lobby, one is first met by a bronze statue of the late President Chiang Kai-shek, the work of sculptor Chen Yi-fan. Behind the statue one enters the four-storey (16.5 m) high rear lobby, which has round renaissance pillars and a granite floor polished to a mirror sheen. The sunlight entering through the high windows projects soft and elegant hues around the white-painted interior. A red carpet stretches from the main door and runs up the staircase. In the center of the stairway stands a bronze bust of Sun Yat-sen, the Father of the Republic.

Chen Pan-ku, whose father died in the 1947 "February 28th incident," entered this great doorway for the first time on 4 March 1991, when he and six other victims' relatives were invited here by the president. His father had been a frequent visitor to the Governor-General's Office under the Japanese occupation. When 40 years later Chen followed his father's footsteps into this same building, he was "filled with all kinds of emotions."

The few dozen paces from the main entrance to the foot of the staircase have been trodden by countless foreign dignitaries and by ROC citizens from every walk of life. This is the path followed by every one of the president's invited guests.

Climbing the stairs, one arrives on the third floor. The late President Chiang Kai-shek's office, the president's reception room and "Chiehshou Hall," the palace's largest meeting room, are all here.

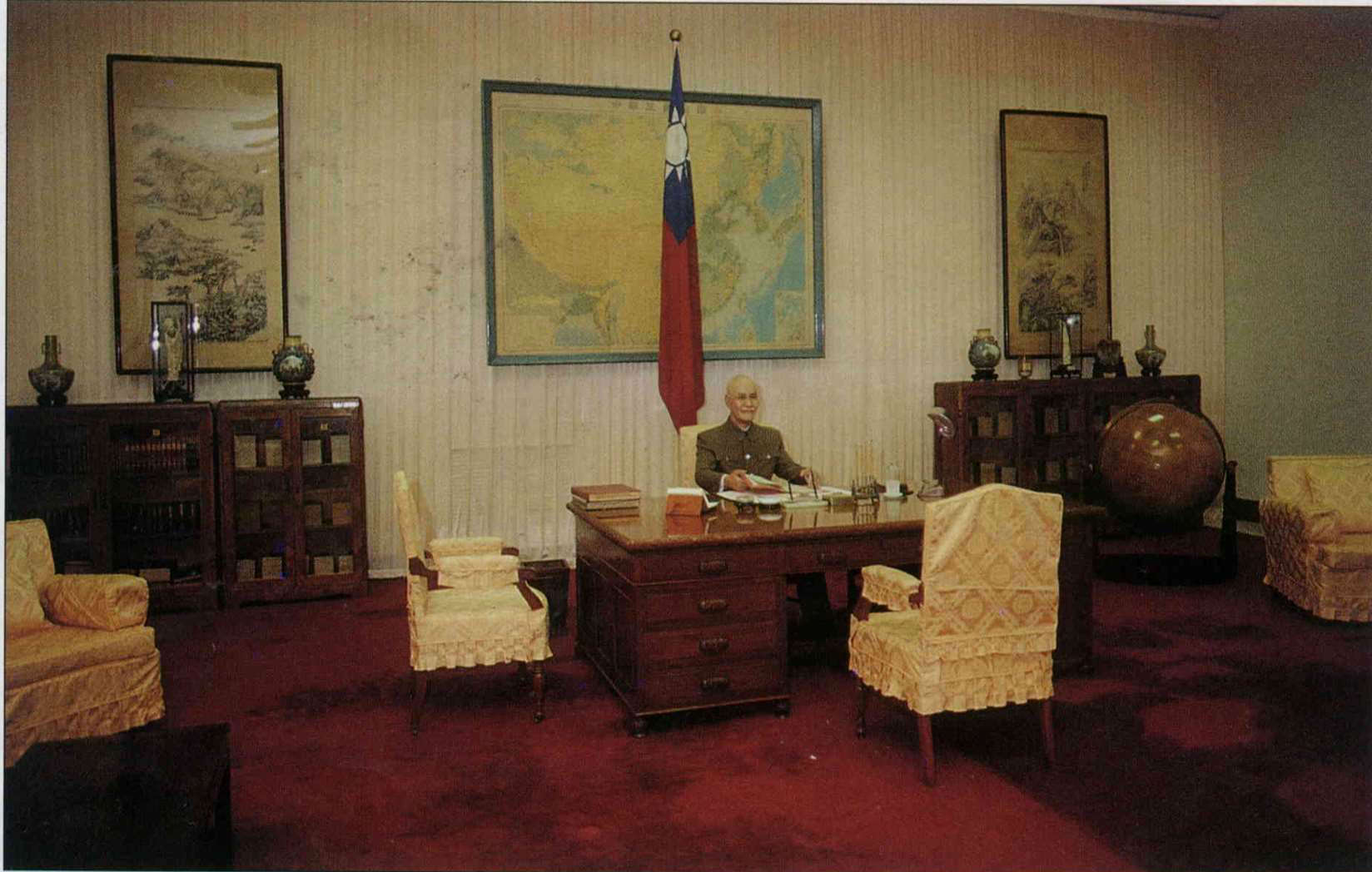

After Chiang Kai-shek's death, the Office of the President preserved his office in its original state as a permanent memorial. But to enable the public to see it, President Chiang's office has now been moved to the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, where it has been reconstructed in its original form and has been open to the public since October. Meanwhile the original room in the Presidential Palace has been refurbished to house a display of medals of honor, awards and gifts presented to ROC presidents by other countries over the years.

In the past, when the late President Chiang Kai-shek was in his office, he would often change out of his military uniform or Sun Yat-sen suit and into a long smock. On many occasions the sound of him admonishing high-ranking officers or officials would ring through the quiet corridors. Li Mu-chang, who from 1950 onwards served the president tea and kept his offices clean, remembers how sometimes when officials emerged from Chiang's office they would be pouring with sweat and would even turn the wrong way along the corridor.

President Chiang also often received visitors in his office, but he made it his rule never to drink tea during a meeting. When his aide-de-camp called for tea to be sent in, this was a sign that it was time for the guests to be on their way. "Even foreigners knew about this rule. When tea was served, you took your leave."

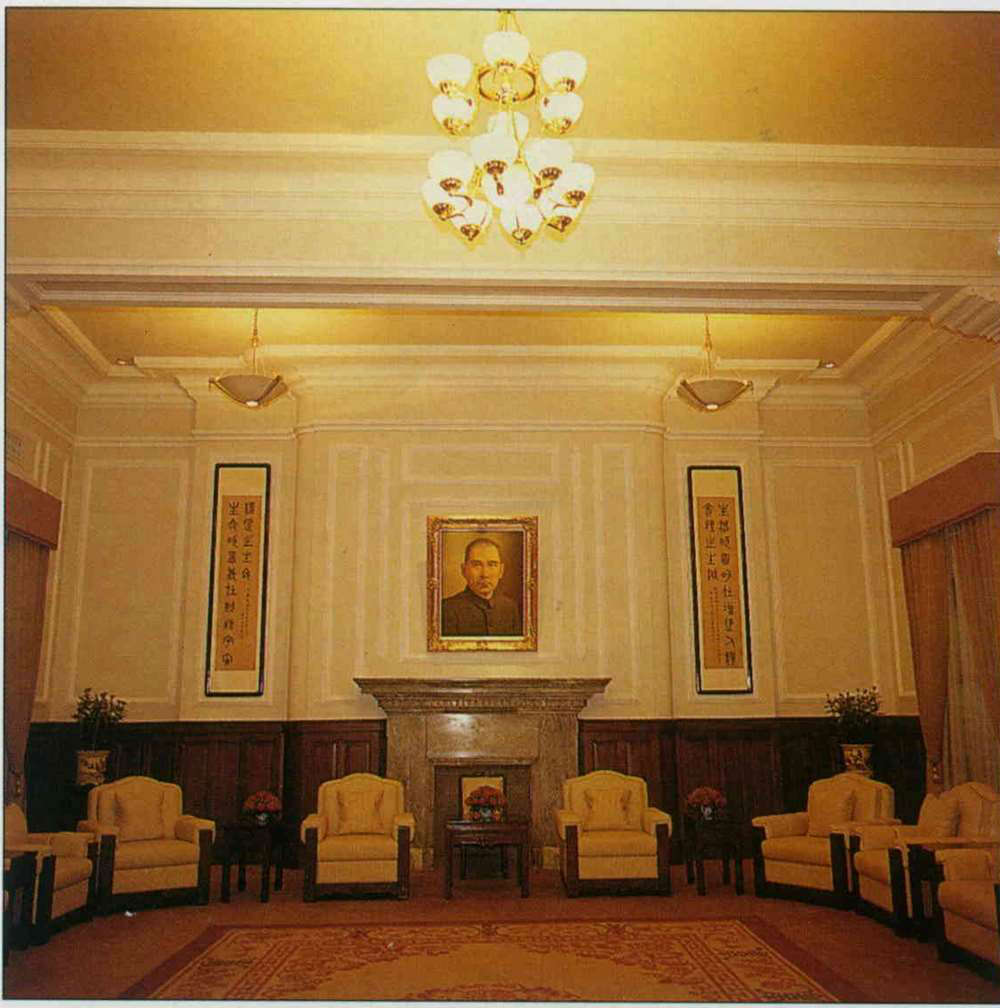

Next to Chiang Kai-shek's office is the president's reception room. A small corridor which runs between the two contains a number of yellow armchairs where guests' attendants or bodyguards can relax. The armchairs were taken out of the reception room a few years ago when it was refurnished and rearranged.

The president's reception room is where the president receives his visitors, such as foreign VIPs and officials, groups of farmers, fishermen, industrialists or business people from within the ROC, each year's "ten outstanding young people," citizens commended for their good deeds, and so on. In President Chiang Kai-shek's day, the Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, US President Eisenhower, King Hussain of Jordan, the Shah of Iran and many other foreign heads of state came here. And because of the tense national and international political situation of the time, President Chiang would also often hold meetings around long tables set up in this room. On the day in 1963 when northern Taiwan was struck by the powerful typhoon Gloria, water and electricity supplies to the Presidential Palace were cut off, but President Chiang still continued work as usual and met with high-ranking military officers.

The scholarly President Yen Chia-kan was well known for the pleasure he took in receiving guests. One year, when the Ministry of Education invited some 50 presidents of world-famous universities to visit Taiwan, President Yen received each of them individually; and because of his special love of art and culture, he also received many people active in these fields.

In President Chiang Ching-kuo's time in office, with his populist style, many ordinary people were visitors here, including his "11 old friends" whom people loved so much to talk about; and after President Lee Teng-hui took office, following the great changes in the ROC's political environment, families of February 28th Incident victims, opposition party leaders and representatives, students demonstrating against major state policies and other dissident figures began to appear among the visitors here.

For 40 years, the Office of the President has always served its guests Lungching tea. Li Mu-chang, who is still in charge of the president's reception room today, has observed that guests rarely drink all their tea, especially women. "They're probably afraid they'll need to go to the toilet," he says with a laugh.

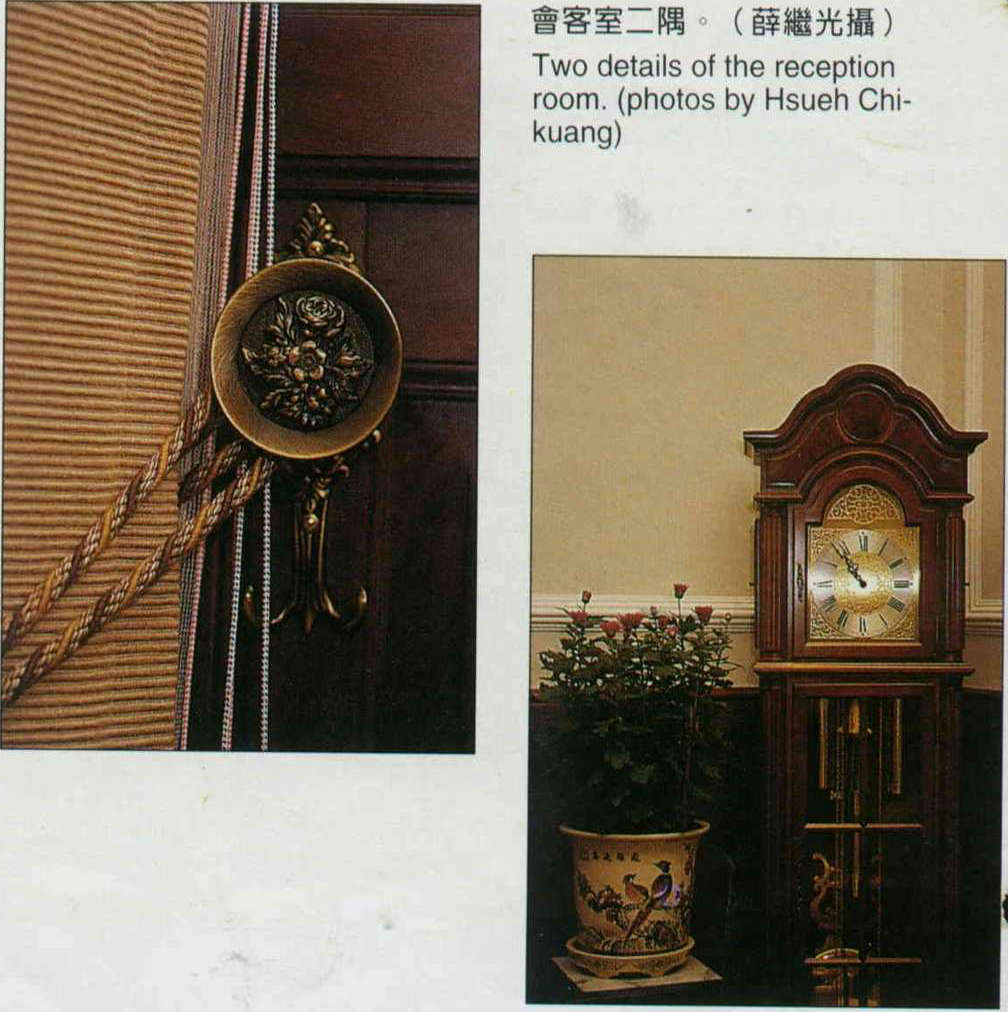

The reception room has long been the part of the Presidential Palace that has received the greatest public exposure. Two years ago, the simple old carpet and armchairs from the frugal days of national reconstruction were replaced. Now the walls and furniture are all coordinated in a gentle cream color, and the carpet is decorated with Chinese motifs.

Back in President Chiang Kai-shek's day, the walls were hung with his own calligraphy and Mme Chiang's Chinese-style paintings. But in recent years these have all been moved to the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, leaving only a treasured scroll presented to Chiang by Sun Yat-sen in 1923 with the inscription "Seek a matter's cause in its origins; Seek its beginnings in the inception of the idea," and a pair of large-character scrolls in the hand of the old party and national leader Wu Chih-hui, inscribed "Our purpose in living is to improve the lives of all humankind; The significance of our lives is in creating the continuing life of the universe."

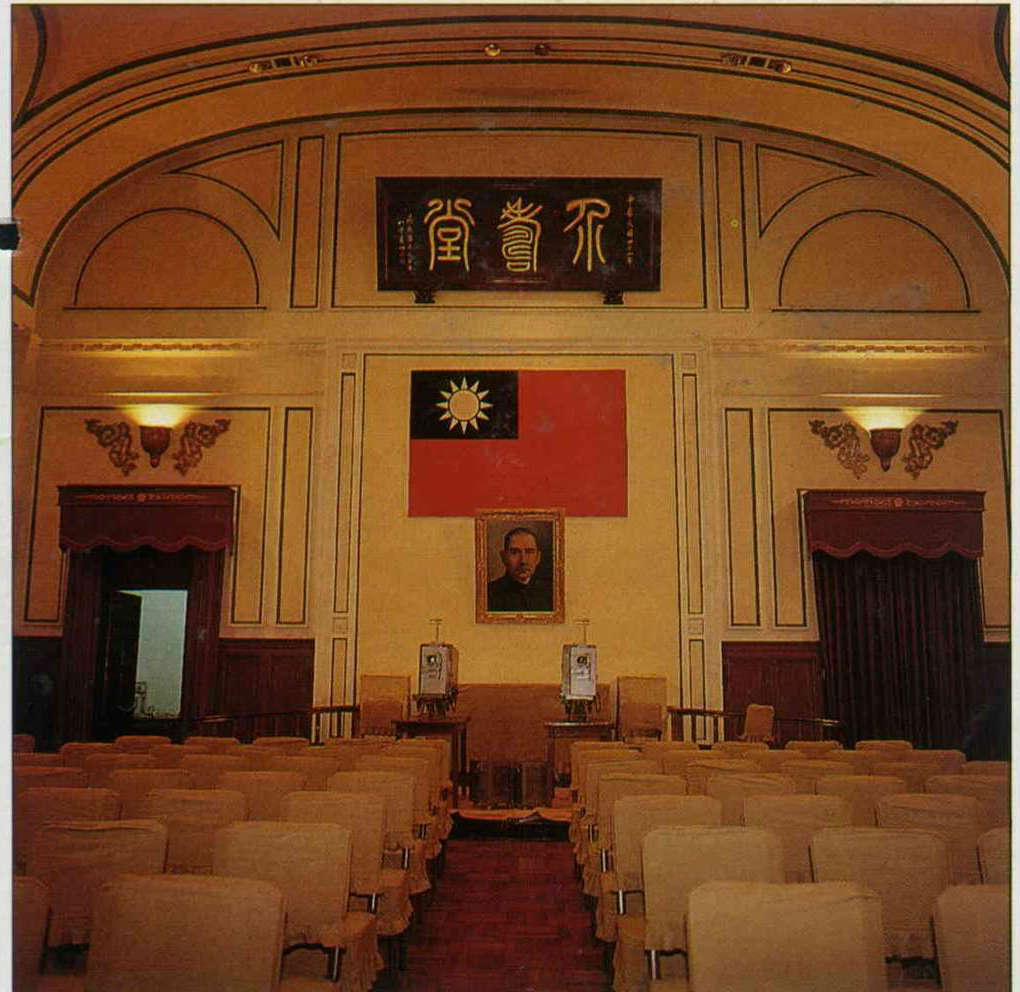

"Chiehshou Hall," which in recent years has become well known as the venue for the Presidential Palace concerts, is the ROC's highest-ranking meeting room, and can seat around 400 people. Ever since the building's days as the Japanese Governor-General's Office, it has been a place where many matters of state policy, national livelihood and military strategy have been decided, and is also where presidents down the years have taken their oaths of office. Furthermore, the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Meeting on the morning of the first Monday of every month, the president's tea parties, the president's press conferences, the Presidential Palace concerts, and even meetings of Presidential Palace staff, are all held here. This is where, at just such a monthly meeting, industrialist Shih Chen-jung put forward his idea that Taiwan should become a "Silicon Island," and Academia Sinica president Li Yuen-tseh has also been here to report on Taiwan's science and technology policies. Chiehshou Hall itself is a large meeting room. The special curvature of its high, domed ceiling gives it an especially good acoustic resonance. It is said that when someone is speaking on the stage, even without a microphone, they can be heard clearly in every part of the room. Violinist Lin Chao-liang, who has performed here, has said that Chiehshou Hall's acoustic almost rivals that of many European palace concert halls.

Above the stage hangs a plaque inscribed with characters in the ancient great seal script, written by Wu Chih-hui himself at the age of 88. Because President Chiang Ching-kuo was wheelchair-bound in his latter years, to make it easier for him to get on and off the stage, ramps were installed on both sides, and these have been retained to this day.

Chiehshou Hall also has another important function, for this is where state banquets are held. Generally speaking, Chinese food is served in the Western style. The meals are cooked and served by chefs and waiters from the Grand Hotel, and accompanied by live performances of Chinese classical music. Protocol at state banquets demands that the Chinese and foreign guests should sit alternately, but one person who has been involved in planning state banquets observes that if the guests are from a non-English-speaking country, the language barrier often creates an atmosphere of awkwardness. "Apart from the two heads of state, for most of the other guests the meal is rather heavy going." And because the hall can only accommodate around 100 dinner guests--usually divided equally between the two countries--and as all the officials are invited together with their spouses, the number of invitations is limited. "This makes compiling the guest list for any state banquet a big headache."

Chiehshou Hall is located in the central crossbar of the "日" character, and from the corridors here one can look out into both the northern and the southern courtyards. Under the Japanese occupation, the courtyards were used for parking bicycles, but today they are the place where Ministry of National Defense staff do their morning exercises.

Leaving Chiehshou Hall, one is almost at the end of the visit route. Before going down the stairs to the Great West Door, one passes solid, heavy pillars of Hualien marble, which is nearly as hard as Taiwan jade. Because the rear part of the Presidential Palace is almost entirely occupied by offices of the Ministry of National Defense, the Great West Door is the one through which the defense minister enters and leaves the building. The visiting public will leave by this door.

Because the Presidential Palace houses the highest organ of state power, ever since the Japanese occupation era there have been many popular rumors of its "secrets." The most widespread one is the story of the "tunnels."

Rumor has it that beneath the palace are several tunnels, one leading to the Bank of Taiwan on the other side of Paoching Road, another leading to the Taipei Guest House, and even one which reputedly goes all the way to the president's official residence in Shihlin, to give the head of state an escape route in emergencies. There are even rumors which claim that below the Presidential Palace there is an underground military base.

"It really is all completely imaginary," one high-ranking official who has worked in the Presidential Palace for over 10 years says half despairingly. "There is a military base, but it's not underground, it's above ground: everyone knows that in the rear part of the Presidential Palace there are offices of the Ministry of National Defense and the General Political Warfare Department." Under the Japanese occupation, there really was a tunnel linking the Governor-General's Office to what is now the Bank of Taiwan, and it was used as an air raid shelter during allied air attacks; but it has since been sealed off. Today there is an ordinary underpass under Po-ai Road connecting the Presidential Palace with the Ministry of National Defense, for the convenience of MND staff passing between the two. But an officer at the MND reveals that at several points in this subway there are heavily-locked steel doors; we are told that these lead to emergency air raid shelters.

The tall central tower on top of the Presidential Palace is also the object of much curiosity. Every day at dawn and at 5:50 each afternoon, the public can watch the flag raising and lowering ceremonies, in which two military policemen hoist or take down the national flag on top of the tower. But just what kind of world is hidden inside the tower?

In fact, the only purpose the tower serves is to allow the flag to fly a little higher; there is nothing special inside it. An elevator inside the tower from the Japanese occupation period was long ago sealed off for safety reasons, and today when the MPs want to raise the flag they must climb up a winding wooden staircase. The flag-raising platform on the outside of the tower is high and windy, and so the MPs must attach themselves to the inside of the tower using mountaineering karabiners. There has never been a single accident, except for once when an MP's helmet was blown off by the wind.

It is worth mentioning that the tower's flagpole, which has been jokingly called "The Greatest Pole Under Heaven," is made up of five large, medium and small cannon barrels joined together. A few years ago when the flagpole had to be replaced because of rust, the president's office specially commissioned a fengshui master to calculate an auspicious day for raising the new pole.

The Presidential Palace, which arouses so much curiosity and bears so many associations for people on the outside, is opening its doors. Although behind the veil of mystery there are no scenes of breathtaking splendor, its significance as a symbol of the nation and its historical value make it well worth visiting nonetheless.

[Picture Caption]

p.6

A photograph of the governor-general's office taken in the 1920s, shortly after it was completed. The Japanese flag is flying outside, and soldiers can be clearly seen in the arcades. (courtesy of Li Chung-yao)

p.7

The majestic, towering Presidential Palace has stood for almost eighty years, and is still the seat of the ROC's highest leader.

p.8

All the entrances to the Presidential Palace are guarded by military police. They must remember every face which goes in or out, and the registration number of every high-ranking official's car, to maintain strict security. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.9

A bronze lamp standard base in renaissance style, outside the main entrance. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.10

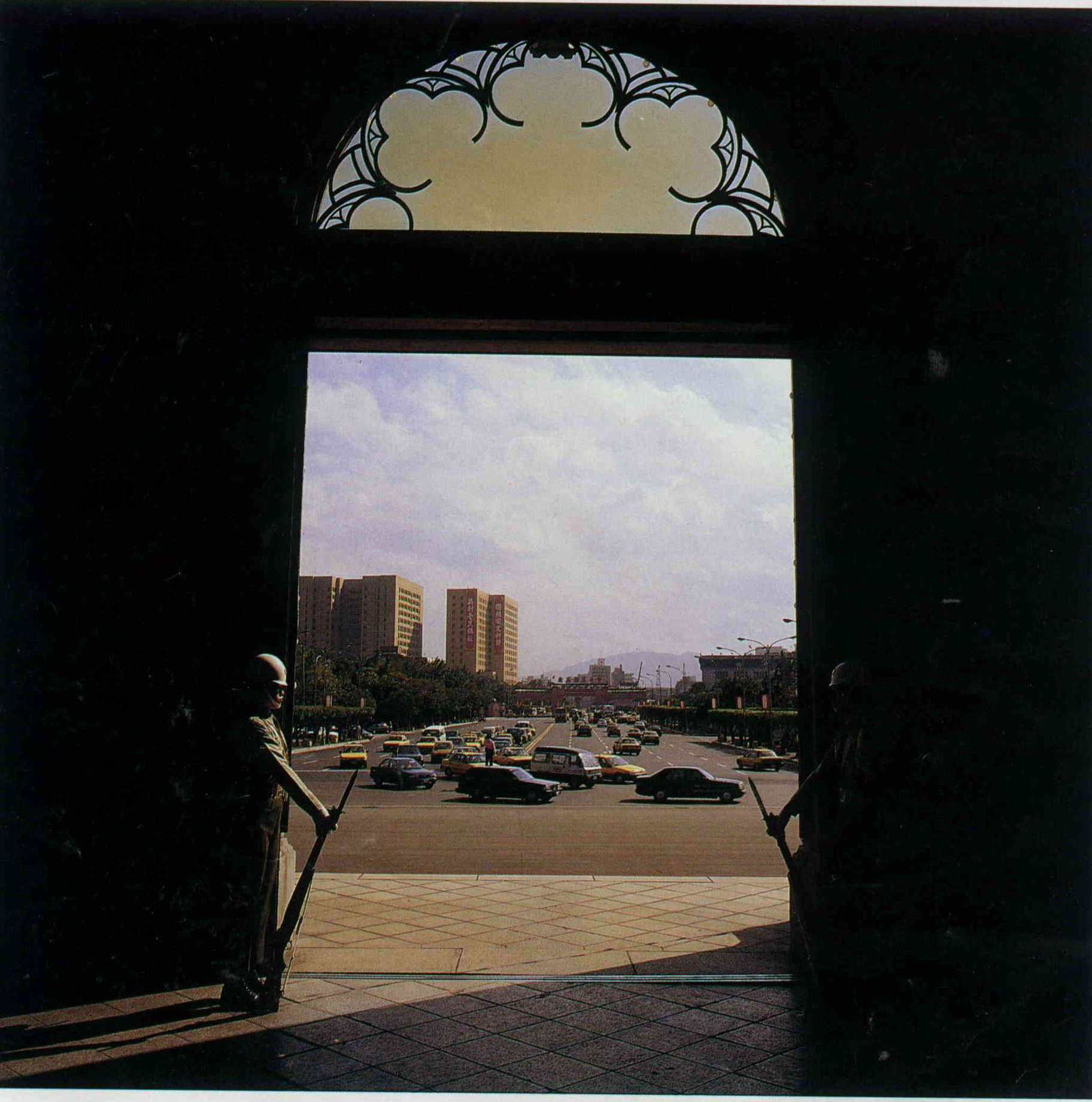

The public at large has always only been able to look at the Presidential Palace from the outside and imagine, but do you know what the world looks like from the inside, looking out?

p.11

The stylish main door of the Presidential Palace is used by the president and his guests of honor. Other officials, even including the president's secretary general and cabinet ministers, cannot use this door.

p.12

The stylish, light-filled lobby is the route by which foreign dignitaries enter the Presidential Palace. From here, the famous branching staircase leads up to the main function rooms. Many foreign guests like to have their pictures taken here.

p.13

A bust of Dr Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China, stands over the center of the staircase.

p.13

The rear lobby is around four storeys high. The curvature of the ceiling concentrates sound. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.13

A neoclassical Corinthian pillar. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.13

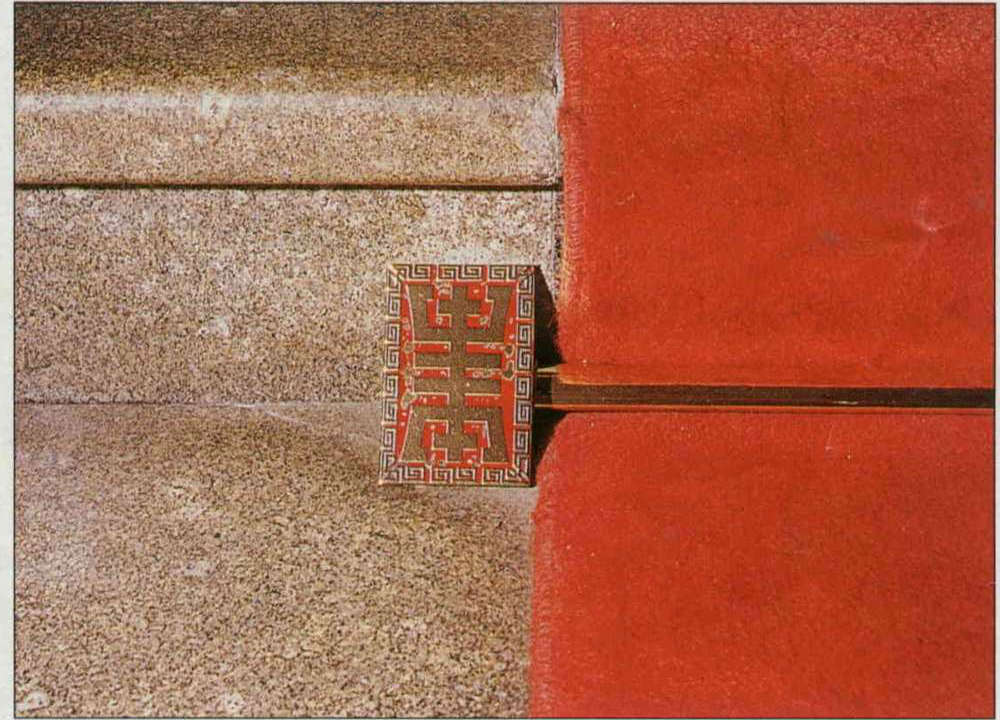

An exquisitely designed stair rod. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.14

Chiang Kai-shek's office, which has now been moved and put on display in the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, reveals Chiang's frugal character and the austerity of the period of national re construction. (photo by Cheng Yuan-ching)

p.15

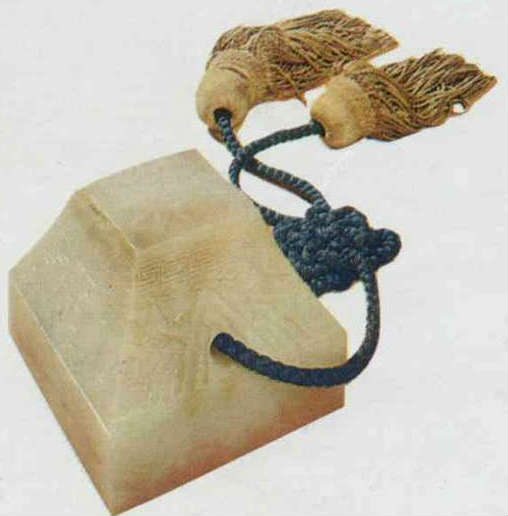

The Seal of the Republic of China represents the nation and is used on diplomatic documents such as credentials, instruments of ratification and acceptance, full powers and exequaturs. Cut from green jade, it weighs 3.2 kilograms. (courtesy of the Office of the President)

p.16

The Seal of Honor is used by the president when conferring honors and decorations, and is applied to citations for medals, commendations and other honors. It is made of white "mutton fat" jade and weighs 4.3 kilograms. (courtesy of the Office of the President)

p.17

The president's reception room is where he receives guests from all walks of life, and is the part of the Presidential Palace which receives the most media exposure.

p.17

Two details of the reception room. (photos by Hsueh Chi kuang)

p.18

Chiehshou Hall is an important meeting room for state occasions. Many historic events have been played out here.

p.18

Chiehshou Hall's domed ceiling gives it a superb acoustic, making it an excellent place for meetings and concerts alike.

p.19

The pillars one passes before descending the stairs to the Great West Door are in marble almost as hard as Taiwan jade.

p.20

Visitor's Route Through the Presidential Palace

Presidential Palace floor plan

(Plan drawn by Lee Su-ling from materials coutesy of Li Chung-yao)

The majestic, towering Presidential Palace has stood for almost eighty years, and is still the seat of the ROC's highest leader.

All the entrances to the Presidential Palace are guarded by military police. They must remember every face which goes in or out, and the registration number of every high-ranking official's car, to maintain strict security. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

A bronze lamp standard base in renaissance style, outside the main entrance. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

The public at large has always only been able to look at the Presidential Palace from the outside and imagine, but do you know what the world looks like from the inside, looking out?

The stylish main door of the Presidential Palace is used by the president and his guests of honor. Other officials, even including the president's secretary general and cabinet ministers, cannot use this door.

The stylish, light-filled lobby is the route by which foreign dignitaries enter the Presidential Palace. From here, the famous branching staircase leads up to the main function rooms. Many foreign guests like to have their pictures taken here.

A bust of Dr Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Republic of China, stands over the center of the staircase.

A neoclassical Corinthian pillar. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

The rear lobby is around four storeys high. The curvature of the ceiling concentrates sound. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

An exquisitely designed stair rod. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Chiang Kai-shek's office, which has now been moved and put on display in the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, reveals Chiang's frugal character and the austerity of the period of national re construction. (photo by Cheng Yuan-ching)

The Seal of the Republic of China represents the nation and is used on diplomatic documents such as credentials, instruments of ratification and acceptance, full powers and exequaturs. Cut from green jade, it weighs 3.2 kilograms. (courtesy of the Office of the President)

The Seal of Honor is used by the president when conferring honors and decorations, and is applied to citations for medals, commendations and other honors. It is made of white "mutton fat" jade and weighs 4.3 kilograms. (courtesy of the Office of the President)

The president's reception room is where he receives guests from all walks of life, and is the part of the Presidential Palace which receives the most media exposure.

Two details of the reception room. (photos by Hsueh Chi kuang)

Chiehshou Halls an important meeting room for state occasions. Many historic events have been played out here.

Chiehshou Hall's domed ceiling gives it a superb acoustic, making it an excellent place for meetings and concerts alike.

The pillars one passes before descending the stairs to the Great West Door are in marble almost as hard as Taiwan jade.

Visitor's Route Through the Presidential Palace Presidential Palace floor plan (Plan drawn by Lee Su-ling from materials coutesy of Li Chung-yao)