Building Paradise in the Classroom

Laura Li / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Phil Newell

February 2002

As the lunar new year approaches, so does the university aptitude examination for the 2001-2002 academic year. This exam, which will be held in early February, has been in use for only two years, and the subject matter remains undefined. Across the entire country, the families of more than 146,000 students expected to take part are gearing up for battle.

The introduction of aptitude tests and the separation of the examination process from the university entrance process is but one link in the major reforms introduced into education in recent years. Ever since more than 100 non-governmental organizations staged the "410 education reform march" on April 10, 1994, the education reform movement has taken the country by storm, with wave after wave of new policies emerging, so quickly that it is difficult for observers to keep up. Education in Taiwan is now in a state of trial-and-error and friction as a new system gradually takes shape.

1. You receive a beautiful traditional wedding invitation. On it is written: "On Y year and D day, a wedding will be held for our son XX and our daughter XX." What is the full name of the bride?

2. You have a kerosene lamp, a beaker of water, and a bowl filled with a white powdered substance. What is the substance?

The first question comes from the Chinese section of the first national high school basic aptitude test, held last year. This question stumped a lot of bookworms who spend all their time memorizing texts and poring over reference books, but who pay no attention to family matters like weddings and funerals. The latter question, which comes from the recommendation system for the department of medicine at National Taiwan University, is even more interesting: It is said that many top students from famous high schools touched and smelled the white powder and ended up venturing meaningless answers like "colorless and odorless crystal substance." Only one student, a kid from southern Taiwan who obviously knows her way around a kitchen, said nothing, but lit the kerosene lamp, and dumped the substance into the boiling water. Eureka! It turned out to be powdered egg white.

New questions for a new era. If one were to describe education in Taiwan in the past as "exam-oriented," then from these surprising new questions, anyone would have to admit that education today is somewhat different.

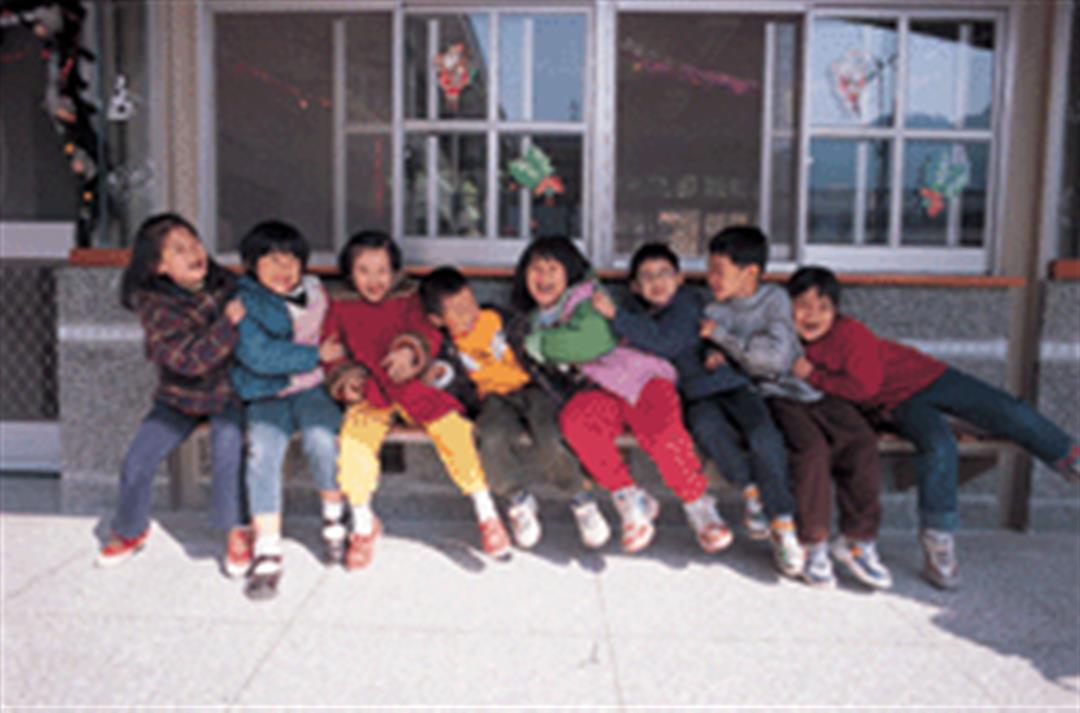

Check out how carefree these children look! The biggest goal of education reform is that each child can learn happily in a way most appropriate to his or her individuality.

A future perspective

Education reform has in fact been a natural product of changes in Taiwan's political and economic environment.

In politics, since the lifting of martial law in 1987, a new democratic system has taken shape. Not only has the Democratic Progressive Party wrested political control from the once dominant Kuomintang, social movements-on behalf of labour, women, environmental protection, Taiwanese culture, and more-have arisen like gathering clouds. Schools, with their long rigidified practices, have naturally been brought under public scrutiny as well. The education reform movement arose as a result, with ordinary citizens taking action at the base level to change their environment.

In terms of economics, since the late 1980s Taiwan's currency has appreciated, traditional industries have largely left Taiwan to invest elsewhere, the country has rapidly transformed from traditional industry to high-tech, and now Taiwan faces the growing challenges of the knowledge-based economy and global competition. Education, which in the industrial era was molded to a framework of "uniform specifications and mass production," inevitably has been found in need of an overhaul.

"The term education reform means using new concepts and new methods to educate children so that they can cope with the new era of the future," says Michael H.C. Tseng, commissioner of the Bureau of Education in the Kaohsiung Municipal Government. Tseng, who was previously executive secretary of the Education Reform Committee of the Executive Yuan, defines education reform thus: "Respecting the right of every child to learn, and allowing each child to develop his or her personal potential to become a complete person."

These were the kinds of ideals guiding the work of the Education Reform Committee, led by Lee Yuan-tseh, president of the Academia Sinica. After three years of visiting schools at all levels, at the end of 1996 this commission produced five main proposals for the modernization of education in Taiwan. These were: relaxing restrictions, treating every student appropriately depending on his or her individual nature, expanding channels for and reducing the hardship of advancement to higher levels, raising the quality of education, and establishing a lifetime-learning society. Based on these five themes, the Ministry of Education produced a 12-point action plan, which went into effect at the end of 1998. Today, three years down the road, results are becoming increasingly visible.

Education reform, from defining directions to concrete implementation, has been an enormous project. Can the stultified old system get through this transformational stress test? Can the deeply entrenched attitude in society that everything should be oriented toward test scores be modified? These are two key factors that will determine the success or failure of education reform.

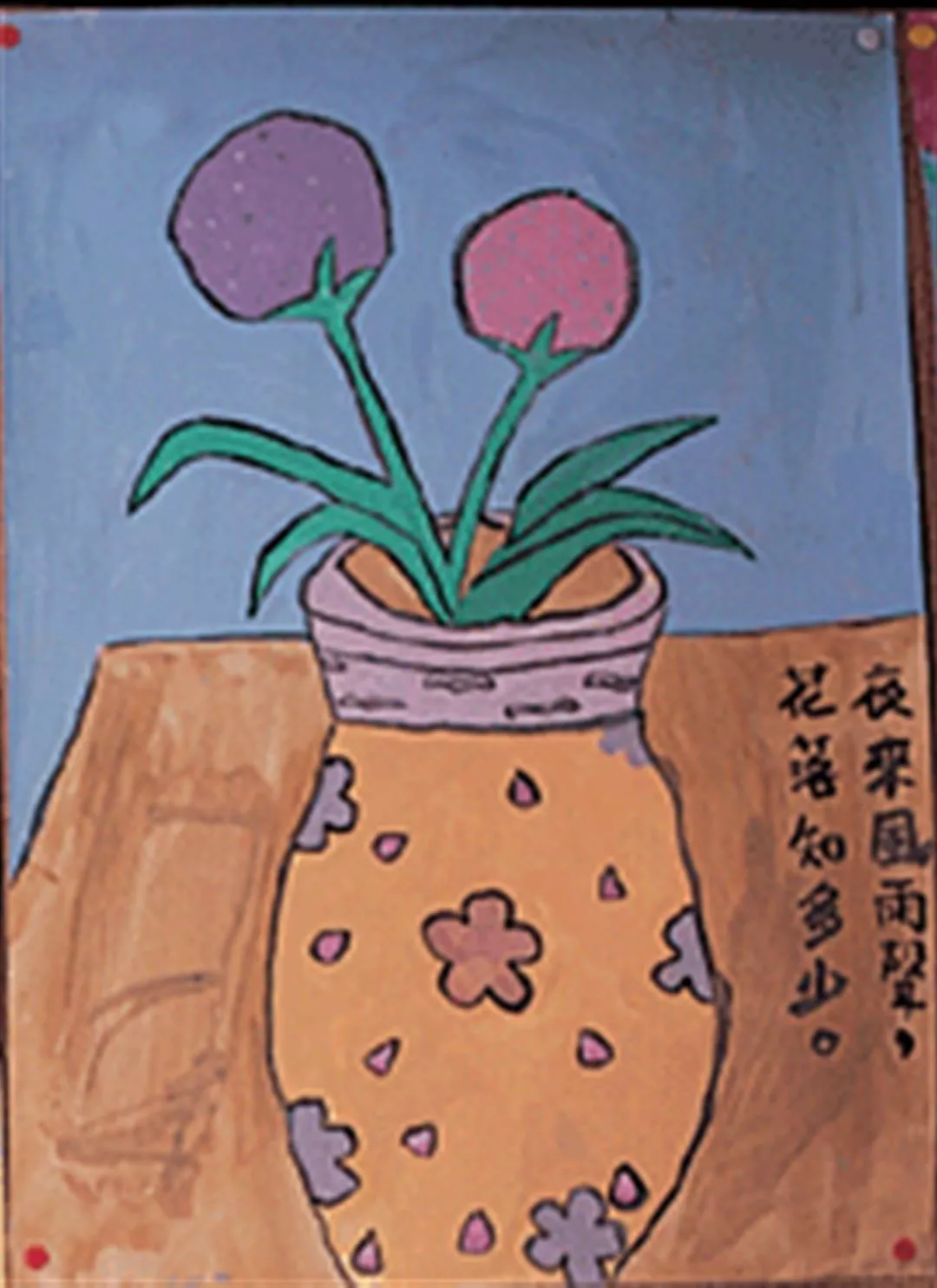

Children can learn anytime, anywhere, even in after school games and in calligraphy and painting practice.

One country, many systems

In terms of transforming the educational structure, Michael Tseng believes that education must be loosened from its previous straitjacket so that schools can be like "educational enterprises," with dynamism, flexibility, and autonomy, so that they can rebuild professionalism and self-confidence.

For a long time, the Ministry of Education treated all schools, public and private, regardless of level, as bureaucratic agencies over which it had control. The MOE exercised detailed management of all aspects of school life, including personnel, accounting, curriculum, and examinations. However, since passage of the Education Basic Law in 1999, power over education has been steadily devolved, and the bureaus of education in each city and county can now make different adjustments depending on their own needs and ideas.

Primary school English is a case in point. To meet the challenge of globalization, one of the main issues of education reform has been when to begin teaching English. Although MOE regulations state that English classes must begin by the fifth grade, Taipei City, which is financially better off, recently announced that starting in September English classes will begin in first grade, while Hsinchu City, which has the golden-egg laying Science-Based Industrial Park, has moved its English classes up two years, beginning them in third grade. Indeed, even within a single city or county, individual schools can speed up or slow down depending upon their resources. To have "one country, many systems" like this is something that was unimaginable under the old regime, in which every action was determined by a specific order from the top.

With the devolution of power and "one country, many systems," various cities and counties have entered into friendly competition, with many new ideas springing up. However, for the poorer or more remote cities and counties, not only are many of the educational policies of urban areas difficult to implement, they are not necessarily even seen as appropriate.

Huang-Lin Shuang-bu, director of the Bureau of Education in Pingtung County, which is located at the very tail end of Taiwan, points out that Pingtung is sparsely populated and has 31 schools in remote areas with less than 100 students each. Many schools lack the funds even for nurses or teachers of art or music, so students do not even have the right to have a stomach ache, much less English language classes.

Huang-Lin further has his doubts about central government concepts like "the global village." These are rather vague and abstract to him, and he would rather put his resources to use teaching students Taiwanese, to develop "real Taiwanese" who know and love their own homeland. Teacher training in Pingtung County focuses mainly on knowledge about Taiwan and concern for local life.

The devolution of power over education means that local governments are now the ones in charge. Not surprisingly, various groups have arisen which are asserting their rights to participate in and monitor educational decision-making at this level. These can complement and balance new local government powers. The most representative are teachers' associations and parents' associations.

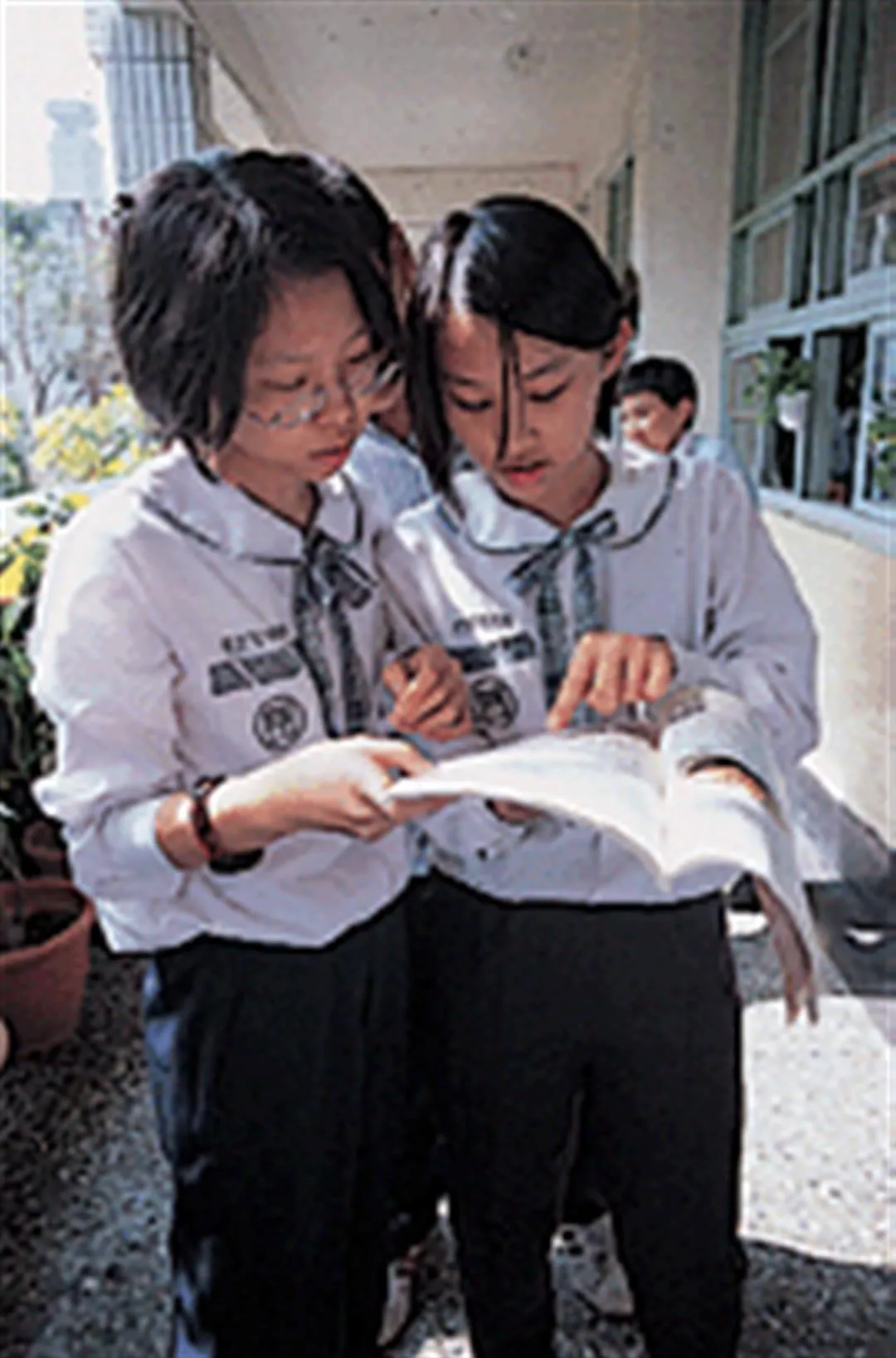

These junior high school students take advantage of a break in their three days of final exams to compare answers; kids are still under a lot of competitive pressure when it comes to advancement to higher grades.

Return to professionalism

With the relaxation of controls over education, power has moved from the central government to local governments and down to individual schools and teachers. The scope of relaxation has been broadened from administrative matters to educational content. Over the past two years, "school-centric" has become one of the most "in" slogans in education. Each school has the right to hire its own teachers, and choose its own textbooks. So now the qualifications of teachers are coming under close scrutiny.

Chan Cheng-tao is a junior high school teacher and director of the education research department of the National Teachers' Association. Based on his own experience, he recalls that early on education in Taiwan was a political tool, so there were all kinds of restrictions and burdens on the teachers colleges, which wanted to avoid developing any capacity for independent thought, skepticism, or critical thinking in their students. Their political philosophy, which he sums up as "Don't think too much and don't do anything out of the ordinary," was reflected not only in rules governing uniforms, hair length, and shoes, but also in prohibiting professors and students from discussing the nature of education itself.

When teachers produced by these colleges entered campuses, they taught children based on the same model, and, using the uniform textbooks edited and printed by the national government, implemented a system of rote memorization of dead facts. Taiwan education became increasingly rigidified, headed for a dead end.

With the unfurling of the banner of educational reform, educational content is no longer dictated by a single source. In September of 1996, the government, starting at the first grade level, began steadily allowing private publishers to produce textbooks on their own, with schools having the right to choose among those offerings which pass a government review.

"Education in the new era emphasizes closeness to real life and localization. It is hoped that students will begin to construct a system of knowledge beginning with the environment around them. In that case, every locality should be encouraged to bring its own special nature to the forefront," said Mike Lee, chairman of the KST Education Corporation, whose primary school textbooks are number one in Taiwan.

The new "integrated nine year curriculum," which came online last September, places schools in the driver's seat, with teachers developing their own teaching materials and textbooks. This should significantly alter future educational content in Taiwan, and has been called another "quiet revolution" in educational reform.

In 1997 the constitutional article requiring a certain percentage of the national budget to go to education was revoked, bringing protesters out into the streets. The evidence shows, fortunately, that education funding has not in fact declined.

Small classes, happy students

Moreover, points out Ou Yung-sheng, a professor at National Taipei Teachers College, "As the content of education is transformed, pedagogy must follow suit and modernize as well." In the knowledge-based economy, countries do not compete in terms of discipline or hard work, but creativity, diversity, and adaptability. To meet these new demands, academe must move in the direction of "lively education" and "creative education."

A critical condition for realizing "lively education" in practice is small classes. The MOE has spent nearly NT$17 billion building more than 10,000 new classrooms and hiring new teachers. Currently, nearly 2600 primary schools around the country have reached the target of no more than 35 students in a class for first through third grade. Teachers entering a classroom formerly faced the pressures of dealing with more than 50 kids; that pressure will now be much reduced.

Professor Ou notes that "the pedagogical spirit of the small class is dynamic education and animated education, so teachers have to put in a lot of extra effort." Field trips are one example of the new philosophy in action. In the past it was very difficult for teachers to take their students outside of class, but that's all changed. This is due in part to the smaller number of students in class. In addition, teachers now have the flexibility to put new outside resources to good use to benefit from the richness and diversity of society. Given the greater amount of wealth in society, there are many volunteer moms with money and free time to support activities, and there has also been a tremendous increase in the number of public and private museums, exhibitions, and performances.

In the three years since the promotion of "the small classroom spirit" went into effect, an educational revolution has been taking place in primary schools. However, the creation of a happier learning environment in elementary school is now running up against the hard reality of regular examinations and competitive pressures to advance in junior high school, which still operates along more traditional lines. This disparity in learning environments may actually make things more difficult for many students, and this is a tremendous fault line running through the ideals of educational reform.

"They relax restraints here and relax restraints there, but in the end kids are still tied into the examination system for advancement," says a frustrated Lu Shu-yuan, principal of the Sanmin Junior High School, which has long been the top junior high school in Kaohsiung City.

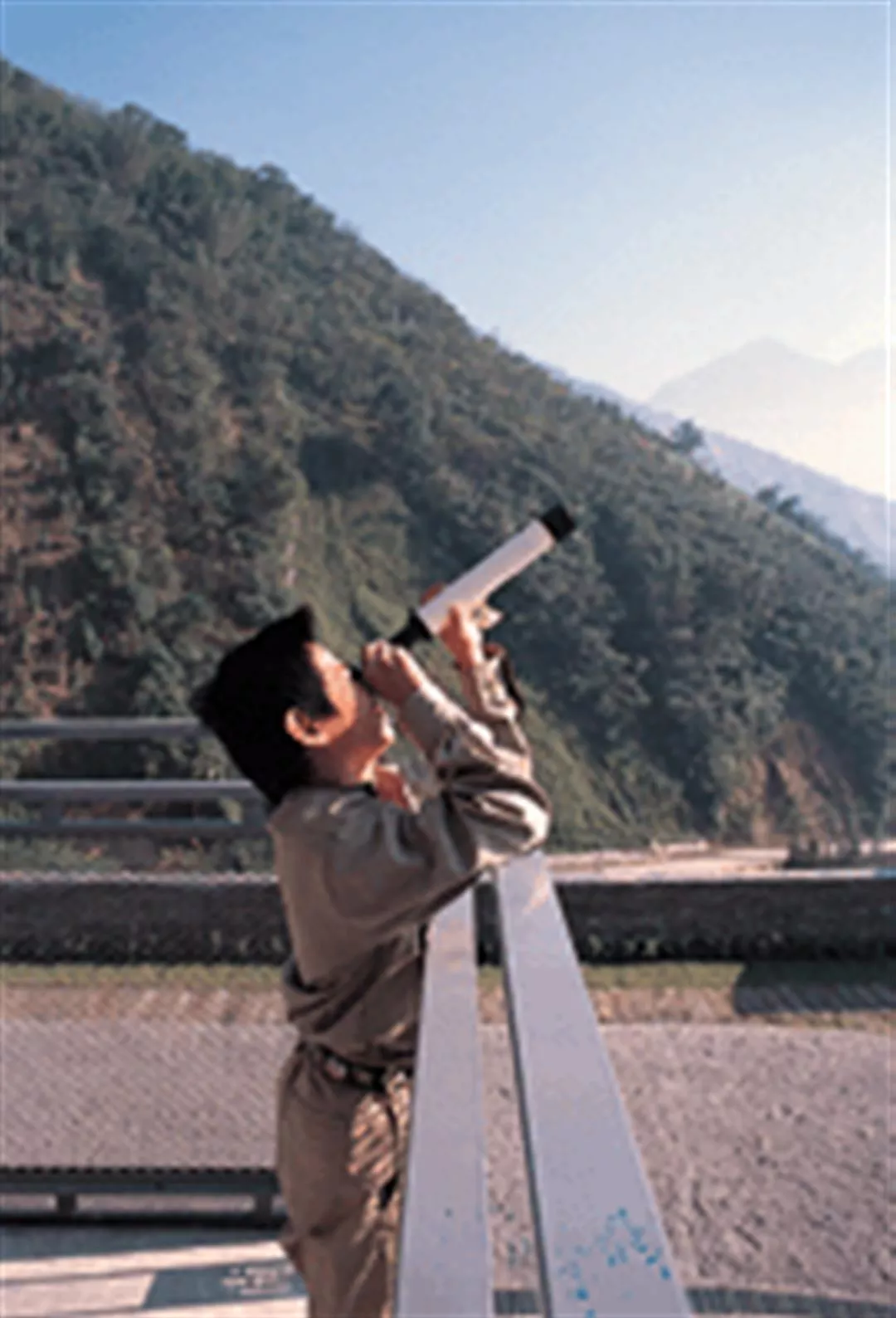

Once they get outside the box, kids find that the universe offers limitless room.

Multiplication and division

To be sure, one of the most difficult challenges for education reform is making advancement less stressful for students.

Going back to the root of the problem, Chou Chih-hung explains that there are two types of high school in Taiwan: academic high schools which prepare students to take the college entrance exams, and vocational schools which train skilled labor for the workforce. From the 1970s to the beginning of 1990s, entrance to these schools was fixed at a ratio of 30:70. No matter how strong the desire of students to continue toward university, seven out of every ten were forced out of the university track and into the vocational track right after leaving junior high (i.e. just before their tenth year in school). These have been the real victims left on the school advancement battlefield.

In an attempt to excise the cancer in Taiwan education-the pressure of advancement-the 410 Education Reform Alliance called for building more academic high schools and universities. In his education reform report, Lee Yuan-tseh suggested that in the future the mainstream of high school organization should be comprehensive high schools (including both academic and vocational curricula). This would sharply increase the number of students who could study in university-track courses, and prevent the excessively early streaming of students.

Since 1991 more than 100 new public and private high schools (including comprehensive high schools) have been founded, so now there are more than 270 such institutions. Meanwhile, the ratio of students entering academic vs. vocational tracks has been adjusted to 45:55. This means that today more than 40% of kids can keep their university dream alive after junior high school.

At the same time, there has been an explosive increase in the number of colleges and universities, from 50 or so only 10 years ago to 127 today. The percentage of students seeking admission who are accepted has risen from less than 30% in the past to about 60% today.

Check out how carefree these children look! The biggest goal of education reform is that each child can learn happily in a way most appropriate to his or her individuality.

New bottle, old wine?

"Multiple channels for advancement and elimination of the joint entrance exam" was to have been another stake through the heart of the high stress system. The MOE has announced new measures for diversifying ways to get into high school and university, and the joint entrance exam has become a thing of the past. In its place is the basic aptitude test, part of the new system of "separating examinations from recruitment."

Chou Li-yu, principal of the Wanfang Middle School in Taipei City, who is the only professional primary- or middle-school educator to participate actively at the forefront of the reform movement, explains: "Basic aptitude is only the minimum bar for advancement. Whether a student is accepted or not depends on their overall performance, including artistic talent, participation in activities and clubs, or classes in which they show particular excellence."

Because the basic aptitude test is only one hurdle, rather than (as with the previous exams) a one-shot effort to survey everything the student learned in three years of junior high school or high school, it can place more emphasis on the overall capabilities of the child. Thus, the scope is much broader-no longer limited to school textbooks-while the questions can be framed in a much more lively and flexible way.

"You definitely cannot guess or accurately memorize the answers for the aptitude test, and even with an open book test the difference among students can be measured," says Chan Cheng-tao of the National Teachers' Association. The basic aptitude test was held for the first time last year, and the lively nature of the questions was eye-opening for everyone. As long as this trend continues, within a few years, the traditional junior high school pedagogy of rote memorization will naturally have to change as well.

However, after crossing the aptitude hurdle, what criteria are used to determine admission? Currently high schools and universities use several approaches, including recommendation as a result of success in a particular subject matter or in academic competitions, application, and grade point average. However, there have been constant disputes in the three years these methods have been in operation. Is it possible to have both diversification and fairness? Should the education system permit the selection of elite students? Or should all students be treated equally? These questions have no easy answers.

Taipei City was the earliest jurisdiction to implement multiple channels of entry for high schools. Many high schools adopted new criteria for admission, including recommendation, weighting of particular classes, a second round of testing (oral or written), or calculation of the overall junior high school grade point average. However, various observers accused Taipei of "raising entry standards arbitrarily and encouraging elitism." Thus, this year these methods will all be discontinued. With the reduction of autonomy for each school to recruit students, the basic aptitude test will become virtually the only criterion. This is essentially a return to the past, in which one test decides the student's entire future.

This is not a painting, but an explanation of a math problem. The new curriculum employs the concept of structural thinking, establishing math concepts with images and hands-on materials. There is now less attention to just crunching numbers.

I want to go to a good school

Can multiple channels of advancement or increasing the percentage of students accepted to higher levels really reduce the pressures of promotion? A girl in her third year of junior high school relates that, in order to prepare for the first high school aptitude test which will be held in May, her school is giving students an average of four to six tests per day, and all club activities have been suspended. Many schools are keeping all their students until 9:00 at night for cram sessions. Students who fall even slightly behind are immediately kicked into remedial classes. In the face of the realities of competitive advancement, the high-sounding ideals of educational reform are but dust in the wind.

"The reason that it is impossible to reduce the pressures surrounding advancement is not that there are not enough schools for students to attend, but that students want to attend good schools!" says Kuo Wei-fan, a professor at National Taiwan Normal University. Kuo, who as minister of education in 1994 first opened the door to educational reform, reveals an astonishing statistic: In his tenure, 70% of the students who passed the joint university entrance exam came from only 30 high schools. Students from the other 100-plus high schools were only there to "fill in the blanks."

It is precisely because there are such large differences in quality between high schools and universities that it is impossible to undo the obsession with getting into a good school. As a result, many of the lower-quality high schools and universities cannot recruit their full complement of students, while the majority of kids are still killing themselves to squeeze into the star schools.

Faced with the gap between the ideal and the real, Chou Li-yu says straight out that for education reform to succeed requires a complete turning upside down of social values. Taiwan society still suffers from "diploma-ism": Companies decide the salaries of their incoming employees based on their academic backgrounds; the government prides itself on the number of PhDs in the cabinet; and students from National Taiwan University or Tsing Hua University have an easier time finding good jobs.

"If Taiwan could elect a president like former British prime minister John Major, whose highest educational attainment was graduation from primary school, perhaps only then will the perverse custom of everyone trying to advance to a higher level of education gradually disappear," says Chou. With a shake of her head and a sigh, Chou says that the deconstruction of social values will require a great deal of time. So long as this dead weight drags on society, it will be a long time before education can be humanized and normalized.

Clacking "wooden fish" together and singing Taiwanese songs can develop stage presence and give the kids a chance to admire one another's talents. Education should always be this lively.

Stability for the long haul

In fact, education reform, transforming the system from its very roots, is a task that could take generations. People should not demand instant results. Many of the criticisms and attacks on education reform derive precisely from this point.

"In education reform in Taiwan, waves of new policies have come along in too much of a rush. It's always the same thing: Before consensus has been built up and supporting measures are in place, the new policies are launched helter-skelter. There are all kinds of disputes and the whole thing goes up in smoke. This kind of thing damages citizens' confidence in education reform," said Sophia Chi-huey Chan, director of the Parents Association in Taipei, who has been involved in education reform since 410.

Take for example the tumultuous launch seven years ago in Taipei City and Taipei County of a trial program to allow junior high school students to pursue self-study. After five years, the program was called to halt. What were the benefits and problems of the self-study plan? How can students be motivated for self-study? How can results of self study be tracked and measured? No answers were ever forthcoming to any of these questions, so that more than 10,000 students served pointlessly as laboratory rats.

The same thing goes for the new primary school curriculum standards implemented as recently as 1996. The new standards were initiated with considerable fanfare, but, even as textbook publishers were editing textbooks for the second semester, suddenly there was the upheaval of the new "integrated nine-year curriculum." One primary school teacher says unhappily: "Those of us who were really enthusiastic about working with the new system are now considered to be fools by our colleagues."

In addition, argues Kuo Wei-fan, who has been following education reform since the beginning, "Too much emphasis has been put on the surface problems, on technical questions, while the spiritual aspect has been ignored." Education reform is supposed to be about humanitarian ideals and building new educational values, but is helpless to do anything about declining morals in schools. Recently there have been a series of incidents of junior high school teachers being insulted or even assaulted by students. These teachers have taken their students to court, trying to have them "reformed" through the judicial system. This suggests that the education system has already lost the capacity to guide students in the right direction.

Education reform certainly has its problems. However, believes Chou Li-yu, after a number of years of education reform, education topics have penetrated into society and the home, and every person can take an interest in and have their say about them. With the development of this kind of open mindset, education, monitored and balanced by various interested parties, will naturally evolve into a form that leaves everyone satisfied.

"So long as the main direction is correct, and progress does not grind to a halt, everything else is a matter of minor adjustments." Like many other persons in the field of education, with regard to the future and the deep problems of education reform, Chou Li-yu is filled with confidence.

Children can learn anytime, anywhere, even in after school games and in calligraphy and painting practice.

Ten Years of Education Reform

1992

April: New plan adopted for junior high school graduates to go on to high school, with two-track system (grades and examination) to replace the old joint exam system.

1994

February: President orders amending of "Teacher Training Law" so that all universities can produce accredited teachers.

April: 410 Education Reform March held by civic organizations.

August: Executive Yuan establishes Education Reform Committee, chaired by Academia Sinica President Lee Yuan-tseh.

1995

July: Civic groups launch "709 Education Reform Train."

August: "Law on Teachers" formally promulgated, allowing teachers to form independent professional associations.

1996

September: Formal implementation of new primary school curriculum, with opening up of primary school textbook market to private publishers starting from first grade texts.

December: Education Reform Committee presents its recommendations.

1997

August: Teachers in primary and junior high schools go on contract system, with schools hiring their own teachers, devolving power over personnel decisions.

September: Ministry of Education announces ten-year compulsory education, with "education vouchers" given to subsidize one year of kindergarten education.

1998

July: Ministry of Education announces introduction of multiple admission channels for high school, and termination after three years of joint entrance exam for academic high schools, vocational high schools, and junior colleges.

September: Ministry of Education announces "integrated nine-year curriculum" for primary and junior high school. Promotion of "Small Class Education Demonstration Plan."

1999

June: "Education Basic Law" completes legislative process.

2000

December: "Education Funding Appropriations and Management Law" announced. Individual schools are allowed to establish endowments; rules governing uses of school funding are relaxed.

2001

May: High school "multiple admission channel plan" fully implemented; beginning of "basic aptitude test."

September: "Integrated nine-year curriculum" goes into effect with incoming first-grade classes.

Source: Ministry of Education, K.S.T. Education Magazine

Clacking "wooden fish" together and singing Taiwanese songs can develop stage presence and give the kids a chance to admire one another's talents. Education should always be this lively.

Check out how carefree these children look! The biggest goal of education reform is that each child can learn happily in a way most appropriate to his or her individuality.

The joint entrance exams for high school and university, which guided education in Taiwan for 40 years, are a thing of past, and pedagogical approaches geared to it are the next to go.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)