No matter where Chinese go in the world, it is easy to identify them as "children of the Yellow Emperor" from their one syllable surnames. A small number of countries such as Japan and Thailand require immigrants to adopt local names, a policy which causes quite a let of Chinese to think twice before migrating there.

Surnames have long been one of the "trademarks" of the Chinese. So how much do you know about Chinese family names?

When Wang An, the renowned computer manufacturer, first got famous in the United States, all Chinese felt proud. Because they could tell just by looking at his family name, spelled phonetically in English, that he is a Chinese.

In recent years, the economy has not been in very good shape overseas, and it has been hard to find a job. One American overseas Chinese relates that though by law employers are not supposed to take into consideration the race or nationality of potential employees, they know who is Chinese just from looking at the resumes--that one-syllable surname is a dead giveaway.

In fact, Koreans and Vietnamese also have one-syllable surnames.

"Some people of Korean origin in Hawaii will add the word 'Korean' in parentheses after their family name to indicate that they are not Chinese," says Yuan Chang-rue, curator of the Department of Anthropology at the Taiwan Museum. He notes that Korea and Vietnam used to be under Chinese rule, so it is not strange to find that their people have adopted Chinese-type surnames.

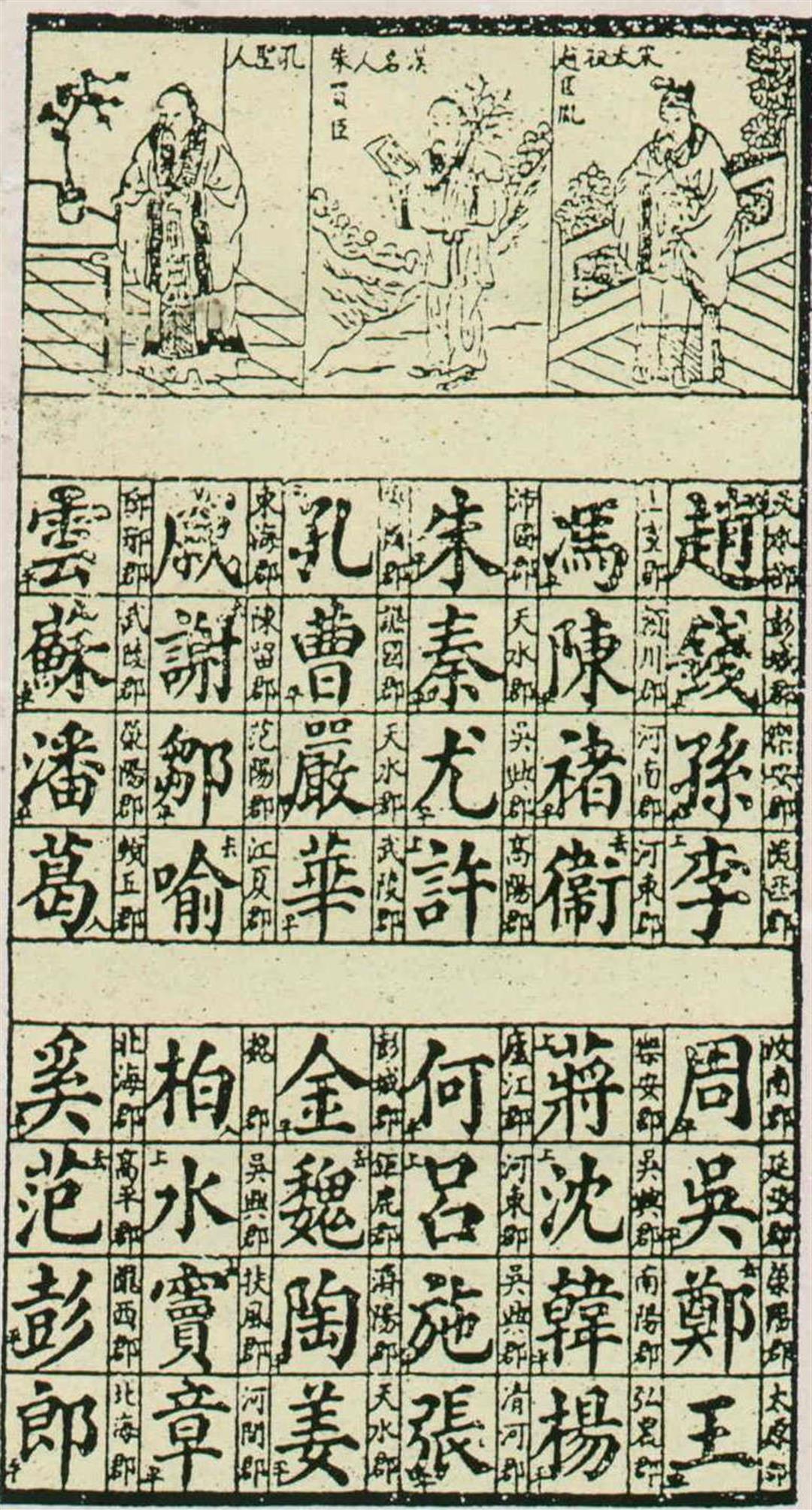

The Book of Family Names is a classic primer for children in China.

Children of the Yellow Emperor

Chinese surnames are not only distinguished by being one syllable long. Compared to surnames in other cultures, Chinese family names were used much earlier and have been seen as more meaningful.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, surnames in Europe originated in the 11th century and became fixed by the 16th, whereas the Chinese already had the custom of passing along the family name as early as the 4th century BC.

According to Chinese legend, surnames originated 5,000 years ago when the Yellow Emperor enfeoffed 14 of his more capable sons. The earliest documented use is in the Spring and Autumn of Confucius, in which he mentions 22 different family monikers. The Spring and Autumn period began 770 years before the birth of Christ.

Most people assume that the Japanese, having sent an emissary to the court of the Tang dynasty (670 to 907 AD) to study Chinese culture, must have picked up the habit of using surnames quite early on. But the custom of surnames belonged only to the nobility, while commoners simply had single appellations. At most, people would distinguish commoners by adding their place of origin or occupation before their names. For ordinary Japanese to have surnames is only something that has come about in the last century.

Chinese surnames came into use so early, explains Yuan Chang-rue, because of unique features of the national culture. Western peoples worship deities, and emphasize the relationship between man and the Supreme Being. Chinese, on the other hand, emphasize relationships between people, and worship their ancestors. Take for example "clan temples," which are maintained by those of the same family name. Then there are "surname associations," which are social organizations. Detailed family genealogies" are maintained, recording the family history. All of these things are closely related to the existence of surnames.

The Chinese have long used the expression "children of the Yellow Emperor," (an early ruler of China), to describe their pedigree. In order to distinguish themselves from the "barbarians" who periodically invaded and settled in China, Chinese have over time clung even more firmly to their precious family names.

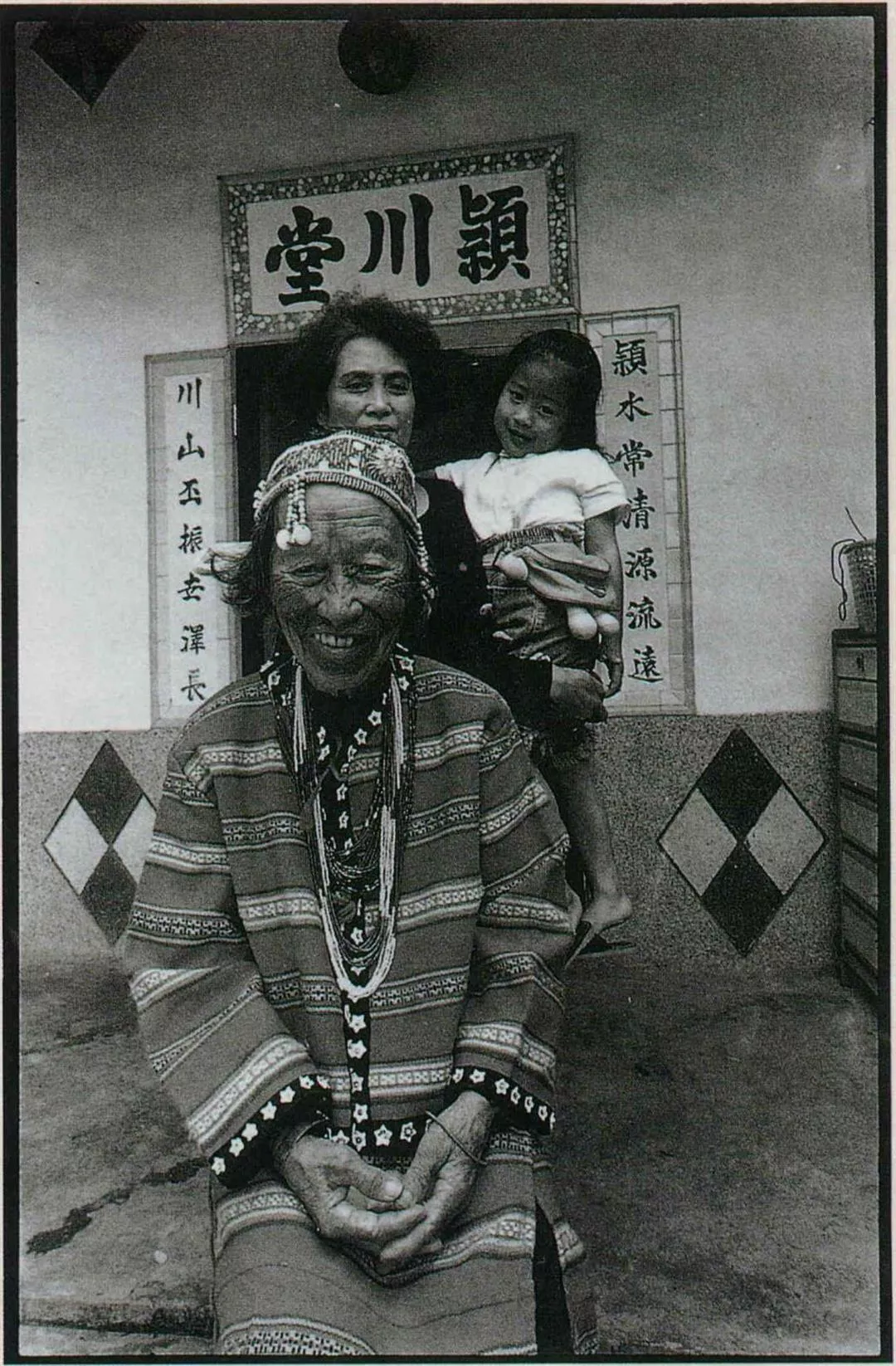

The surname Chen comes from Yingchuan in Henan Province, so many Chens put the characters for Yingchuan on their homes. This family of Atayal aborigines, who have Sinified their surname to Chen, is no exception, despite the fact that their ancestors probably never even heard of Henan! (photo by Ma Teng-yue)

Adopting the wife's surname

In order to ensure the continuation of the family name, Chinese place great importance on sons. If it happens that the family line is interrupted, there are ways to save the situation, such as adopting a son-in-law to carry on the family name.

But it is quite difficult for a man to change his family name by marrying in to another household. Chinese believe that "a real man will never change his name no matter what." Most of those compelled to accept the wife's family name feel that they have betrayed and besmirched their ancestors in doing so.

Therefore, in Guangdong, Fujian, Taiwan, and other places, there is the custom of "sow-names," or "collecting the sow tax," which means that when a man and woman become betrothed, they agree that some of their sons will take the mother's ancestral name, like a tax in kind.

Recently, with the rise of feminism in Taiwan, some people have argued that it should not be legally mandatory for children to take the paternal moniker. Huang Yu-hsiu, a professor in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at National Taiwan University, once applied to adopt her mother's family name of Liu, though her application was refused.

In fact, male chauvinists need not see this idea as "revolutionary." At most, it marks the revival of an ancient custom. That's because Chinese in earliest times took the mother's clan appellation.

According to Yuan Chang-rue, in ancient times, when scattered settlements were coalescing into the feudal system, existing symbols of places of origin evolved into the written characters for family names. China was at that time a matrilineal society, and in fact the Chinese word for surname, hsing, [姓 姓 ] is a composite of the characters for "woman" [女 女] and "birth," [生 生] and can be literally explicated as "the child to whom a woman gave birth."

Moreover, historical records indicate that most of the earliest Chinese family names used the radical for "woman" in the character itself. Thus we can find names like Chi [姬 姬] (the surname of the imperial family of the Chou dynasty), Jiang [姜姜] (the ruling family of the kingdom of Chi), and Ying [嬴 贏] (the rulers of the kingdom of Chin). The ancient Chinese of this matrilineal society understood the idea of eugenics, and developed surnames to avoid marriage between persons of very close bloodlines.

Eventually, as China evolved into a patrilineal society, the old surnames changed. The feudal nobility of Chou took local place names to identify their clans; the use of these shih surnames (as distinct from the hsing or matrilineal family names) became a mark of the aristocracy, and it became a matter of pride to have a shih. Naturally, in adopting shih, clans gave up their hsing.

"By the Warring States period, there were enormous changes in society," states Chen Chieh-hsien, director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the United Daily News. "Confucius' teaching was spread to all without making any class distinctions, and many ordinary people rose to become high officials." Also, in the Chin and Han eras (from the 3rd century BC to the 2nd century AD), an imperial bureaucratic system was established, and the feudal system disintegrated. Shih no longer indicated high rank or power, and the distinction in status between the matrilineal hsing and the patrilineal shih was lost. Reflecting this, today the words hsing and shih, as well as the combined form hsing-shih, are essentially interchangeable in modern Chinese.

The uniting of two family names in wedlock is a great event for Chinese people.

All in the family

No matter how far apart they may be in time or space, people with the same hsing-shih need only go back far enough in their family genealogy to discover common ancestors. Thus, for example, the ancestors of those named Chen trace their lineage back to the Emperor Shun, while those of the Lin clan trace their roots to Pi Kan, an aristocrat of the Shang dynasty era. This is what Chinese mean when they say, "all the same family if you go back 500 years."

In Fuhsing Rural Township in Changhua County, Taiwan, there is a "surname association" for the Nien clan. According to their genealogy they are the descendants of a great Jurchen warrior. Despite their non-Chinese origins (the Jurchen being ancestors of the Manchus), three hundred years after first migrating to Taiwan, many of the Nien clan can speak only Taiwanese. Nevertheless, says Nien Huo-ying, the director of the surname association, when they hold their great ancestor worship ceremony each year on March 31, an event to which five or six hundred of the 6,000 Niens in Taiwan will come, they follow Jurchen tradition in their dress and ceremonies.

In today's industrial society, many people have lost this sense of identification with the clan name. Especially for those with the most common surnames, there is little sense of camaraderie upon meeting someone of the same name. It has even gotten to the point where the ancient taboo against marriages among people of the same surname has been dispensed with.

But for those who bear unusual surnames, there is still some sense of family when meeting someone sharing the moniker.

Teng Sue-feng, who works in a magazine, has been very clear about the origins of her hsing-shih ever since high school, when she read in Mencius that "Teng is the name of a small country." When she went to the United States to study, she ran into a classmate of the same name, and the two joked that they almost certainly were long-lost sisters.

On the mainland, where it is still common for people of the same surname to be concentrated in the same place of residence, the feeling among those with common surnames is very close. If you offend someone, you might just be offending their whole village, and this has caused many inter-clan feuds which have lasted centuries.

According to a recent report in the Hong Kong Ming Pao Daily News, in the mainland some feuds that have lain dormant for 40 years have recently been rekindled. In a certain county in Sichuan, the Liu and Hsu clans, living in neighboring villages. have been going at it for more than a century, generation after generation. The Liu family entered the origins of the quarrel into the family genealogy, and banned marriage between any Liu descendant and a Hsu. Alas, love blossomed between a Liu family lass and a Hsu family lad, which so incensed the patriarch of the Liu that he gathered together his clansmen and went to war against the Hsu, leaving two dead and more than 30 injured.

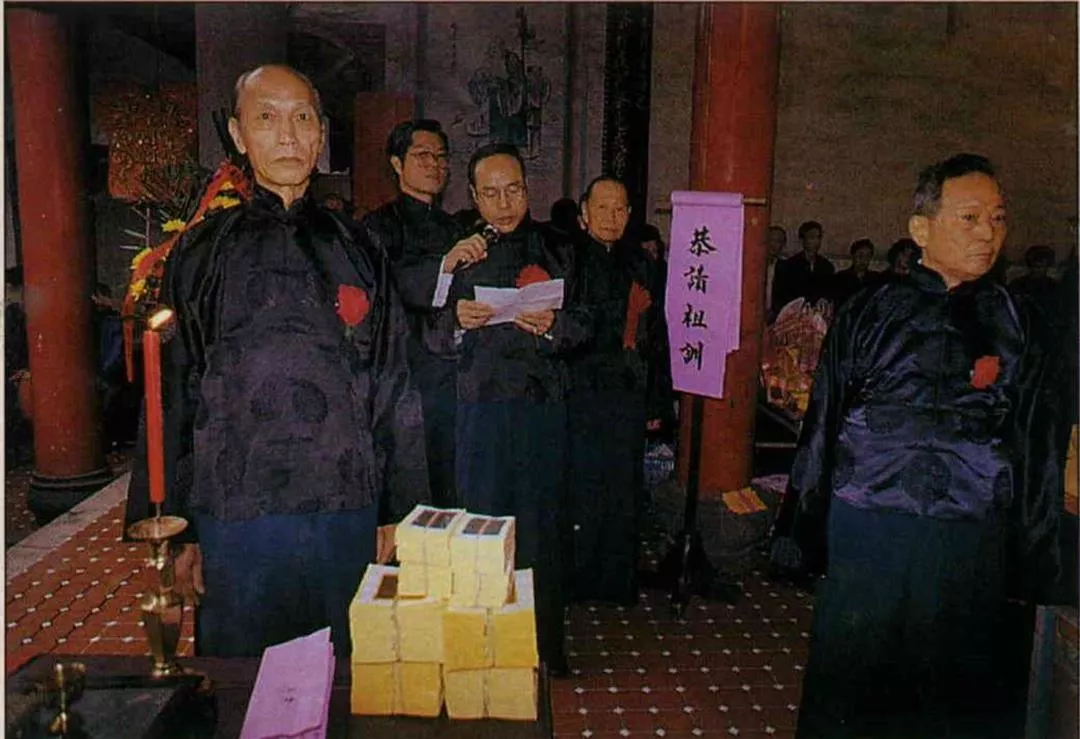

Ancestor worship ceremonies are very solemn occasions. (photo by Diago Chiu)

Surnames from the void

Because of the importance Chinese people assign to surnames, one of the basic primers for schoolchildren is the Book of Family Names. Everyone can recite "Chao, Chien, Sun, and Li; Chou, Wu, Cheng, and Wang" from memory.

Though the Book of Family Names is known in Chinese as the Hundred Family Names, are there really only 100 surnames for Chinese? Ask that question in the Han dynasty and the answer would have probably been "yes." But today there are at least five or six thousand.

Since family names derive from one's ancestors, and some family lines have died out, it would only be logical that the number of hsing-shih decline over time. Obviously, then, a lot of Chinese names appear to have come from nowhere.

The Han dynasty work Feng Su Tung Yi (Penetrating Popular Ways) divides the 100 surnames of that era into nine categories, according to origin: ancestral surnames, posthumous titles, style names, aristocratic names, official posts, names of feudal lands, places of residence, special activities or skills, and profession.

Later, some people had their names changed by the emperor either because of some outstanding achievement for the nation or because of some crime. People of the former category got surnames identical to that of the emperor's own family name. Those of the latter type were dubbed after inauspicious objects, leading to handles like Huei, meaning "venomous snake." Some surnames were changed to avoid bad fates. Thus Confucius' student Tzu Kung had the double surname Tuan Mu, but his descendants changed the name to Mu to avoid being targeted by members of a clan with a feud against the Tuan Mu line.

Other hsing-shih developed because people omitted some brush strokes when writing to save trouble, adopted characters to match the sound of their names, or just plain wrote the originals incorrectly. Thus sometimes the surname Chang, originally looking like

鄣, mutated into this: 章.

Another major reason for the increase in the number of names was that many people with double surnames (now a rarity) changed them into single characters. In fact, the single-syllable surname, now considered a "trademark" of Chinese, was by no means the mainstream in the early days. In the dynasties Shang (1766 to 1154BC) and Chou (1122 to 255 BC), more than half of surnames were double characters. But these were continually simplified so that by the time people in the Sung dynasty (960 to 1120 AD) collated the Book of Family Names, double surnames were only about one-tenth of the total.

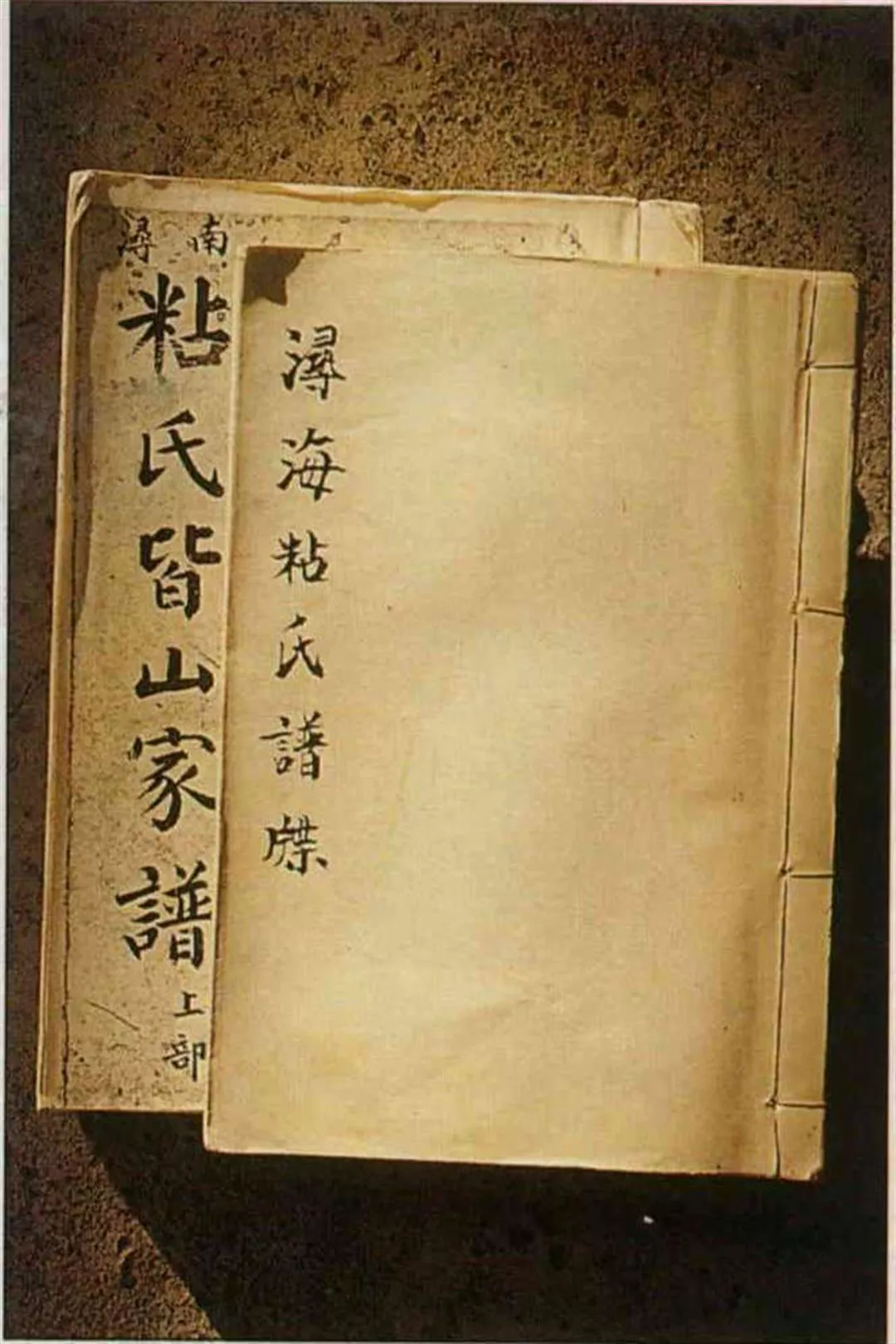

From their family genealogy, the members of Taiwan's Nien clan know that they are descendants of a great Jurchen warrior.

Rice, Fields

Amidst the wave of new Chinese hsing-shih, it is especially interesting to take note of the sinification of the names of non-Han minorities.

Like Europeans, minorities on the Chinese periphery have polysyllabic names, like Ashingoro, the family name of the Manchu emperors of the Ch'ing dynasty. In the process of sinification, to avoid discrimination, many of these people dropped their obviously non-Han surnames in an attempt to fit into mainstream society. Thus, for example, when the Hsiao Wen emperor of the Northern Wei dynasty undertook the enforced assimilation of peoples, all the Hsienpei people adopted Chinese hsing-shih.

In the time of the Ch'ing dynasty, because their Manchu clan names would have been extremely long if written out phonetically in Chinese, only given names were used in the historical records. Later on, revolutionaries trying to discredit the regime told people that the Manchus had no surnames at all, a scandalous idea to Han Chinese. "This is because in China, only bastard children lacked family names," explains Chen Chieh-hsien. After the founding of the Republic of China, many Manchus who were worried about being mistreated adopted monosyllabic surnames.

In Taiwan, the local indigenous people have also had their surnames altered. First, in the Japanese occupation era they were forced to take on Japanese names. Then, after the arrival of the Republican government, their names were sinified for the convenience of the residential registration system.

As for how their names were altered, many aborigines still knew their original surnames, and adopted Chinese names based on the sounds or the meaning of the original. For example, there is a clan among the Ami whose aboriginal name, Patsilal, means "sun," so they are now called either Jih ("sun") or Yang ("sunlight") in Chinese. There are other cases in which the residential registration officers "donated" their own family names to indigenous households, truly a case of "using materials that happen to be close to hand."

"Many descendants of the Pingpu [a long-assimilated group of aborigines] are surnamed Pan [潘]. They were told that this in an excellent character because it includes the characters for rice [ 米], and fields [田] next to a water radical. But in fact, it really was insulting them, because,"points out Chen Chieh-hsien, “looked at another way the character for rice and fields add up to the character for 'barbarian.'" [番]

There are also many indigenous people surnamed Kao(meaning “high”) because they live in the forests, or Tai(because they are people of Taiwan).

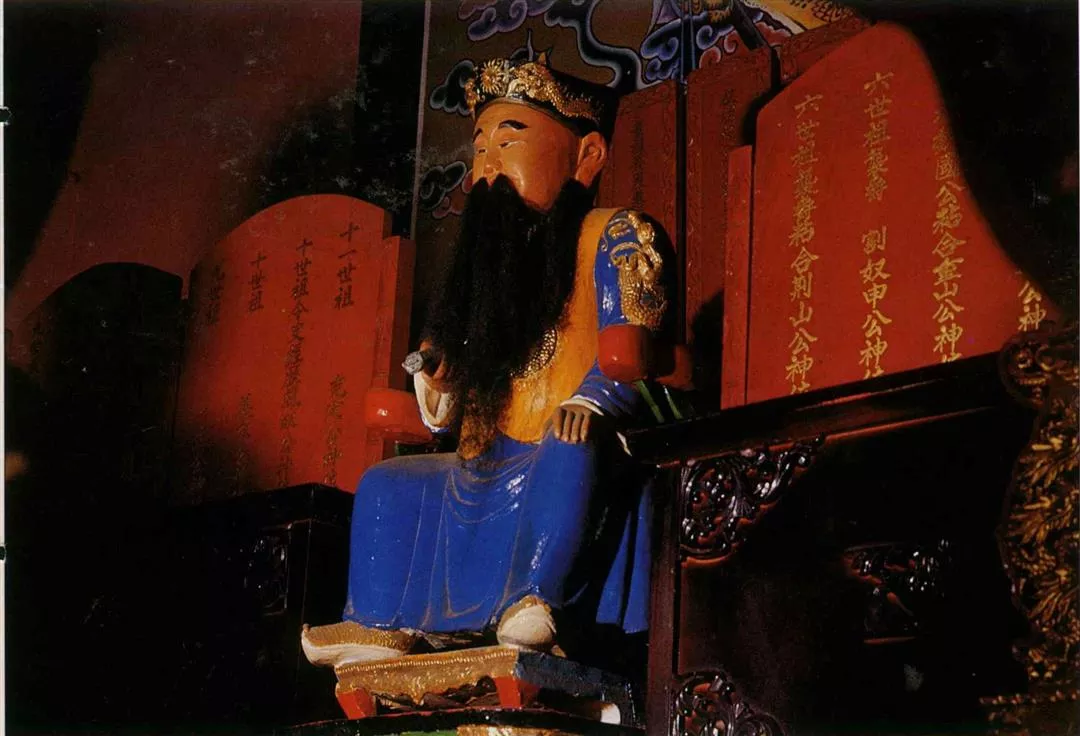

This statue and these ancestral tablets are part of the Nien clan ancestral hall.

Atayal descended from Confucius?

Tai Ching-nung, a professor at National Taiwan University who hailed from Anhui Province in mainland China, once tried to find out if he had relatives anywhere in Taiwan. Through the Ministry of the Interior he discovered several households surnamed Tai, but they all turned out to be aborigines.

In Jen-ai Rural Township of Nantou County there are several families named Kung, the family name of Confucius. But they are 100% Atayal aborigine, not likely to be related to the Sage. It looks like this refutes the idea that because the Kung family line has continued uninterrupted since Confucius that all those surnamed Kung "come from this family alone, and no other."

In general, Chinese people take their hsing-shih seriously, and would never change unless absolutely compelled to .But there are exceptions to every rule. In the traditional hierarchy of the five relationships in China, the emperor-subject relation ranks above the family relationship. Thus if one is given a surname by the emperor, it is an honor to accept it.

Take for example Cheng Cheng-kung, a general of the Ming dynasty who resisted the Ch'ing dynasty to the end. He was given the surname "Chu" by the Ming emperor, which, as everyone knew, was the surname of the imperial family, or the kuohsing. In order to honor Cheng Cheng-kung's achievements in Taiwan, there is a rural township in Nantou County called "Kuohsing," as well as "Kuohsing" wells in both Taichung and Changhua. Cheng is commonly known in Western histories as "Koxinga," derived from the Chinese kuohsingyeh, meaning "Lord of the Imperial Surname." The tradition of giving kuohsing can be traced back as far as the Tang dynasty. After Li Shih-min established the dynasty, he dubbed his most accomplished ministers Li, so that today Li (or Lee) is the most widespread surname among Chinese.

It's strange that Chinese people are so superstitious about names, yet are so willing to donate their surnames to others. Not only did the emperor act this way, wealthy families would also assign their family names to their servants, just as the Jia family does in the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber. But Yuan Chang-rue explains the apparent paradox: "If I give you my surname, it means that henceforth we are of the same clan, and you must be loyal to me."

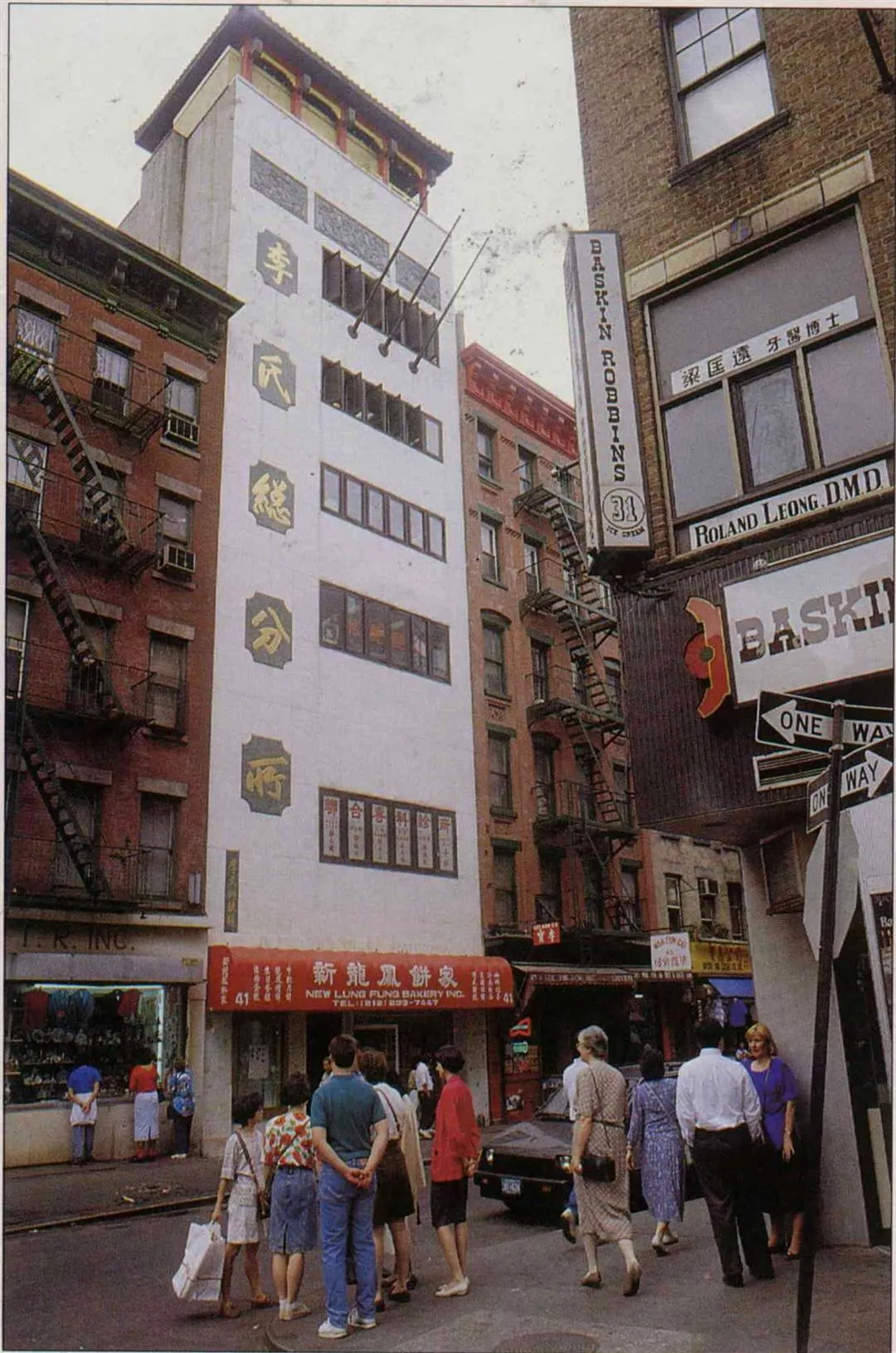

Surname associations are a "trademark" for Chinese overseas as well as at home; the photo was taken in New York. (photo by Pu Hua-chih)

Taiwan's Japanese surnames

"Those who are not of my kind must also think differently than I." Japanese seem to believe this rather firmly. At the end of the Japanese occupation era in Taiwan, the colonial regime attempted to "Japanify" the Taiwanese, part of which was the adoption of Japanese surnames.

Though Chinese have always attached great importance to family names, after 50 years of Japanese rule in Taiwan many Chinese traditional concepts had weakened; moreover the Japanese offered incentives (more rations) to those households which adopted Japanese appellations. Moreover, it was not just anybody who could take a Japanese name-- only civil servants, teachers, village mayors, or local notables were eligible even to apply, and the application had to be reviewed and approved--so that, in a way, the Japanese turned the unpalatable change in surnames into a kind of honor comparable to the traditional imperial surname.

Chen Kuo-tai, who runs a glass shop in Hsinying, recalls that his father, a primary school teacher, applied for the surname Motoyama, which in Chinese characters means "Yuan Mountain," because a mountain near the family ancestral home in Fujian Province was called by that title. His motive was like that of Chinese surnamed Chang who emigrate to Japan, who change their name to Nagayumi (which in character form is [長弓], the combination of which two characters makes the character for Chang [張]): All want to make clear that they have not forgotten their Chinese ancestry. In Chen's case, the Japanese were defeated before the name change could go through.

"In those days there were those who envied families who could change to a Japanese surname, as well as those who cursed such families," says Chen. In general, the envious were those of relatively low knowledge and understanding. The better educated, on the other hand, knew that people only changed to Japanese names for some material return, and most turned their noses up at this betrayal of one's own forebears. Therefore, many people who met the qualifications to change their names did not do so. "But," adds Chen, "most families were like my own, and didn't really care one way or the other."

Fortunately the "Japanification" of Taiwan got a late start, or else many people in Taiwan today might not know their ancestral surnames.

In Okinawa, though persons of Chinese ancestry must use Japanese surnames in life, they mainly use their Chinese family names on their graves. Is it a way of making up to one's ancestors? (photo by Huang Li-li)

Surnames and genetics

Perhaps there are those who wonder what difference it can make what your ancestral hsing-shih was. But data suggests that there is a subtle relationship between surnames and genetic inheritance.

You could say that the surname Chang, one of the three most common among Chinese, is a "martial surname." One third of the famous Changs in history are military figures. Legend has it that one of the sons of the Yellow Emperor invented the longbow (the character for which is [弓]), and was consequently given the surname Chang [ 張] (the radical for which is, obviously, "bow").

Meanwhile, China's most common surname, Li (or Lee), has produced countless political leaders, from Li Shih-min, founder of the Tang dynasty, to preeminent figures in contemporary Taiwan (President Lee Teng-hui), mainland China (Li Peng), and Singapore (Lee Kuan-yew).

Now, whatever your surname may have brought you in the past, be it glory or disgrace, don't you feel just a little bit closer to your ancestors?

[Picture Caption]

p.20

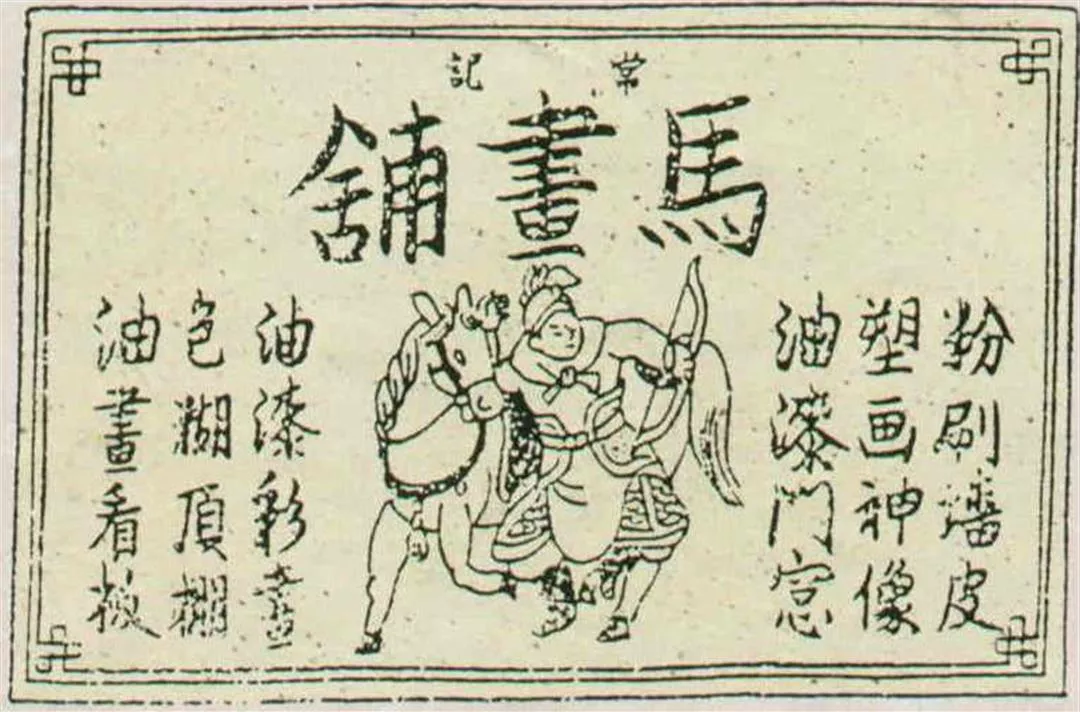

In old China, you could often know the surname of the owner from the shop name. The owner's name--Chang--is clearly marked on this shop that specializes in paintings of horses.

p.20

The Book of Family Names is a classic primer for children in China.

p.21

The surname Chen comes from Yingchuan in Henan Province, so many Chens put the characters for Yingchuan on their homes. This family of Atayal aborigines, who have Sinified their surname to Chen, is no exception, despite the fact that their ancestors probably never even heard of Henan! (photo by Ma Teng-yue)

p.22

The uniting of two family names in wedlock is a great event for Chinese people.

p.23

Ancestor worship ceremonies are very solemn occasions. (photo by Diago Chiu)

p.24

From their family genealogy, the members of Taiwan's Nien clan know that they are descendants of a great Jurchen warrior.

p.25

This statue and these ancestral tablets are part of the Nien clan ancestral hall.

p.26

Surname associations are a "trademark" for Chinese overseas as well as at home; the photo was taken in New York. (photo by Pu Hua-chih)

p.27

In Okinawa, though persons of Chinese ancestry must use Japanese surnames in life, they mainly use their Chinese family names on their graves. Is it a way of making up to one's ancestors? (photo by Huang Li-li)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)