An Upstream Battle to Save the Salmon

Chang Chin-ju / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Phil Newell

January 1995

Ten years ago--before Taiwan had its Wildlife Conservation Law, when no one had any experience breeding endangered species, and when in fact many citizens had no conception of ecological protection at all--the story of the brook masu salmon became the first chapter in the history of the conservation of wildlife in Taiwan.

Thus far nearly NT$100 million has been invested in efforts by more than a dozen agencies to breed the species, which exists in the wild only in the upstream portion of the Tachia River. Sadly, not only have its numbers not increased, none of the seven people who have earned PhDs or MAs through the breeding program hold out very optimistic hopes for the fate of the brook masu salmon.

People have not the power to create life, and to restore a creature with millions of years of evolutionary history behind it to its original state is no simple task. Already more than 3000 days of work have been put in on this project, and the results have been disappointing to the experts. What problems remain? What will happen to conservation efforts on behalf of the brook masu salmon? What have we learned in the process of trying to save a life form from extinction?

On March 26, 1988, more than 200 brook masu salmon fry, each of them tagged for identification, prepared to leave the propagation center built for them by human beings and set out to return "home"--to the Chichiawan Stream at Lishan in central Taiwan.

James Wang, then still a graduate student earning a doctorate in animal ecology from the University of Iowa in the United States, carried the bags of brook masu salmon, each fish representing an investment of NT$300,000. Wang struggled forward, always apprehensive that he would lose his footing on the slippery rocks and wipe out the fish. Finally, the researchers reached the selected spot along the river, and gingerly set their precious cargo of "fish full of dollars" free.

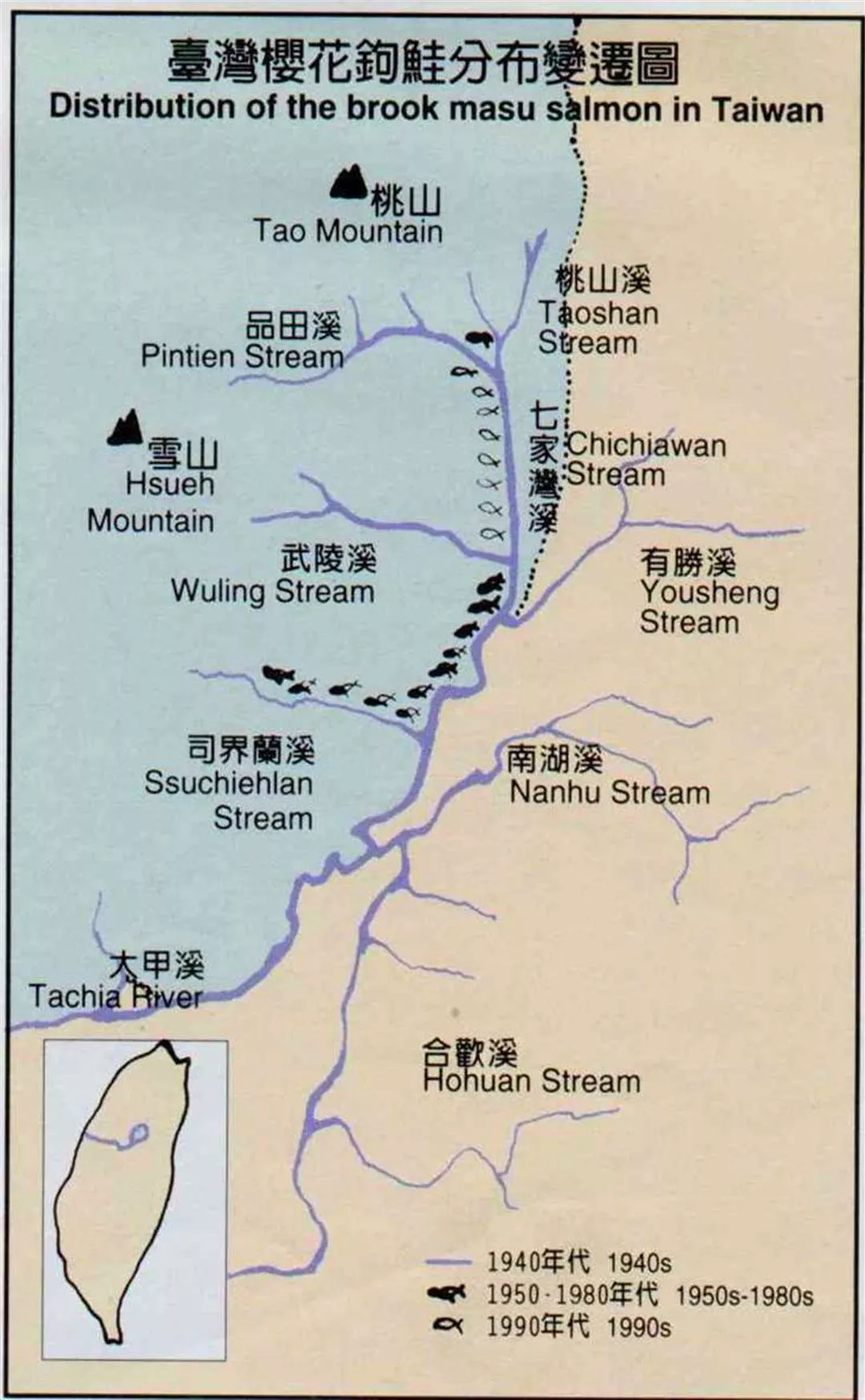

Swimming against the current

Records and scholarly studies indicate that before the 1970s the brook masu salmon could be found in six tributaries feeding into the upstream portion of the Tachia River. Today, a brief twenty years later, ichthyologists have found that there are only about 2,000 of the fish left, and these only in a five-kilometer stretch of the Chichiawan Stream.

Salmon are typically cold-water fish which live in the open sea. It was in the Japanese occupation era that people discovered to their surprise that "there are salmon in the mountains of subtropical Taiwan." Since such a discovery had been unthinkable to scholars of the geographic distribution of species, Taiwan's brook masu salmon (known as the "cherry blossom salmon" in Chinese and sometimes called the "cherry salmon," the "Formosa salmon" or the "Taiwan trout" in English) took on immediate importance. It offers important evidence about geologic history, and has gained international attention. The Japanese declared the fish a natural asset of historic importance, and banned development of the area within 300 meters of either bank of the river.

When it was found in 1984 that this universally famous living fossil was on the verge of extinction, the Council for Cultural Planning and Development listed it under the "Cultural Heritage Preservation Act" as the equivalent of an historic artifact, thus giving the salmon protection under the law. At the same time, the Council of Agriculture initiated a program to bring the brook masu salmon back to its state of nature.

Seeing that few survivors remained of this isolated and precious "national treasure" fish, all of which could be wiped out by an unexpected cold spell, it was not enough to simply patrol the river and to educate citizens. The main effort to restore the salmon population became managed breeding. Not only was a propagation center built on the banks of the Chichiawan Stream, experts were brought up the mountains from the Lukang Branch of the Taiwan Fisheries Research Institute, located on Taiwan's west coast, to select the healthiest young salmon for reproduction.

Lack of coordination among government units has made it difficult to improve the salmon's environment. Though beautiful, the fish faces an uncertain future. (photo courtesy of Shei-Pa National Park)

The return of the prodigal fry

Nevertheless, propagation is but one stage in the process of the restoration of a species. In order to allow the fish to return to and thrive in its natural setting in the Tachia River and its tributaries, it was necessary to understand the reasons why its numbers had been falling, and to find the right solutions to address the fundamental causes of its decline.

In the past, research on the brook masu salmon had revolved around explaining its presence in Taiwan, and in correctly naming and classifying the fish. Today top naturalists at the Academia Sinica, National Taiwan University, and National Normal University are studying changes in the brook masu salmon population, analyzing the water quality in the area where the fish resides, exploring fish pathology, and doing research into the insects the fish feeds on. Scientists have been working together to help the salmon get through this most difficult period in the effort to extend the life of the species.

After two years of work, salmon breeding in Taiwan reached the end of its first phase. Compared to similar work abroad, the reproductive rate was low in Taiwan. Still, there were 250 one-year-old salmon ready to begin the trip back home.

Unfortunately, the Chichiawan Stream little resembled the place that their predecessor generation left behind two years previously.

People have their growth process--from being protected by their family to making their way through school and into society--in which they draw on different environments, and fish likewise have theirs. The brook masu salmon makes different demands on its environment at each stage of its maturation.

As James Wang, the first person to earn a PhD researching this national treasure, explains, in their adolescence the fish must beware of being eaten by birds or by other river creatures, so they often spend their days in the dark places formed where there are many small stones. In typhoon season, they seek out deep pools as refuges so that they won't be washed downstream by the floodwaters. Adults are predisposed to lay their eggs in shallow spots in stretches of the river where the current is not so strong, so that the eggs can more easily settle into the fissures in the rocks.

The brook masu salmon needs different types of habitats as it grows. Eggs are usually laid in places where the water is shallow and the current is gentle, where the eggs will sink easily and lodge between rocks. Fry, on the other hand, tend to select dark places, in order to avoid predators. (photo courtesy of Shei-Pa National Park)

You can't go home again

Therefore, the brook masu salmon needs a river which has gentle as well as rapid currents, and deposits of small stones as well as large boulders. Thus, naturally winding rivers, which carve out deep pools and leave shallow areas near the banks and can offer all types of river topography evenly spaced along their length, are the ideal places for salmon to make their homes.

Sadly, as the brook masu salmon were growing to maturity in their hothouse environment, the environment of the Chichiawan Stream was growing less and less suitable for aquatic life. Tai Yung-ti, the second PhD specializing in the brook masu salmon and currently an associate professor at the National Pingtung Polytechnic Institute, recalls that in the early stages of the restoration project, the only way he could observe the behavior of the fish was to strap on an oxygen tank and go into deep pools. Gradually, as the river became wider, straighter, and shallower, the fish could be observed from the surface of the river.

Although fishing has been strictly prohibited in the area, and the brook masu salmon population increased after the fish were released into the river, such a uniform river could not serve to sustain and protect this precious fish. Ultimately, scholars' worst fears came to pass: After a series of summer typhoons, many of the salmon on whom the hopes of extending the species rested had disappeared. Add to this that there were few suitable spawning grounds and other reasons, and the number of brook masu salmon fell to 500-600, the level at which they remain today.

The key question is this: After investing so much money and bringing together so many talented people, why has it proved impossible to preserve the short five kilometers of the Chichiawan Stream where the species resides?

Tai Yung-ti, who has observed the decline in the fish population since 1986 and is determined to discover the reasons for it, states that the fate of the brook masu salmon is intimately intertwined with the overall development of the Chichiawan Stream.

The brook masu salmon needs different types of habitats as it grows. Eggs are usually laid in places where the water is shallow and the current is gentle, where the eggs will sink easily and lodge between rocks. Fry, on the other hand, tend to select dark places, in order to avoid predators. (photo courtesy of Shei-Pa National Park)

Landlocked salmon

In the 1940s a Japanese zoologist named Shikano Tadao drew up cross-section diagrams of the rivers in western Taiwan. He discovered that most rivers at altitudes of 1500-1700 meters are located on steep slopes and run very rapidly. In comparison, the Tachia River--at about the same altitude--is on a gentler slope. Moreover, it is located in central Taiwan where there are fewer typhoons, so it offers unusually good natural conditions.

As a result of these special conditions, tens of millions of years ago, during the ice age, when salmon could freely swim up and down Taiwan's waterways, groups of salmon, relying on their memory of the water's chemical composition, would swim upstream at spawning season to lay their eggs in the upstream portions of various rivers in Taiwan. In an extreme example of the principle of natural selection, only the strongest could survive the journey home, thus maintaining the durability and health of the whole species. However, when the ice receded, many brook masu salmon were left stranded, unable to return to the sea. They had no choice but to become "landlocked" salmon. But of Taiwan's many waterways, only the Tachia River offered the conditions for the salmon to survive to the present.

Today the Tachia River watershed is no longer what it once was. After the cross-island highway, which follows the Tachia River, was completed, the forests were cut down and orchards planted. Since then, the Tachia has become muddy and turbulent, and the downstream portion has suffered a number of disasters. The brook masu salmon was the first to feel the effects of all this. Agricultural activities have caused the average water temperature to rise by five degrees over the past three decades, and many stretches of the river are now unlivable for the salmon, which does best in water of 17 degrees Celsius.

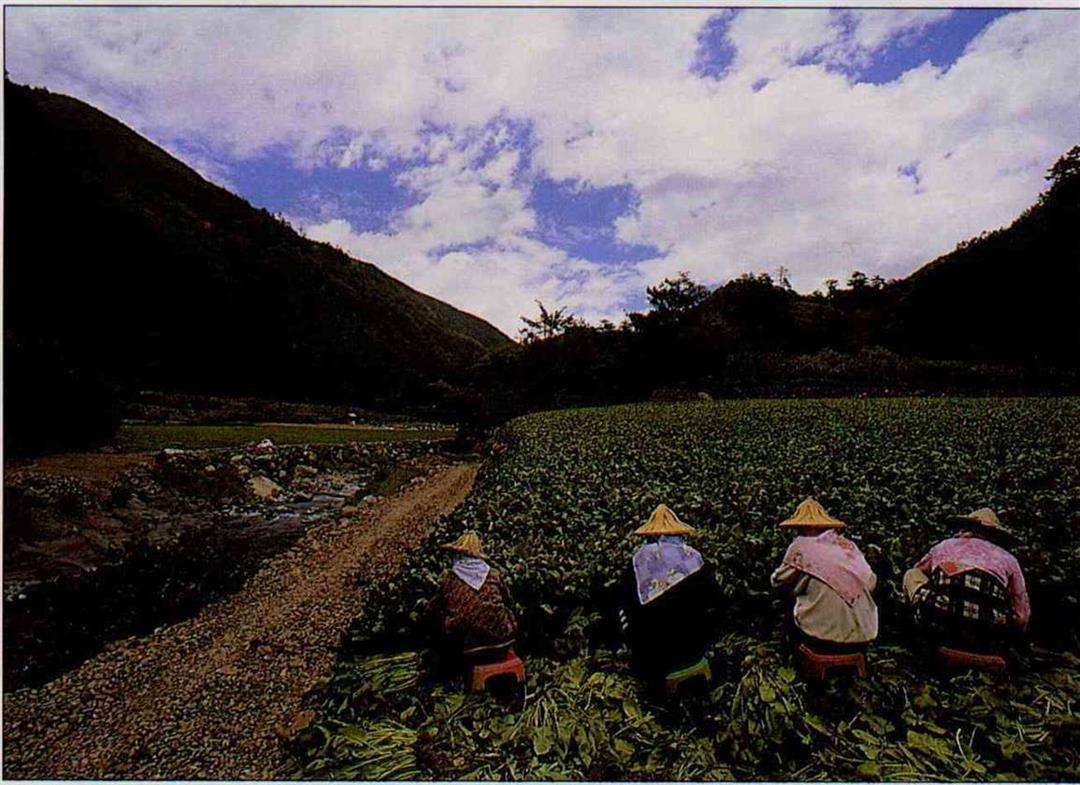

The salmon has been a victim of high altitude agriculture. Yet people are even more the losers. (photo by Vincent Chang)

Fish out of water

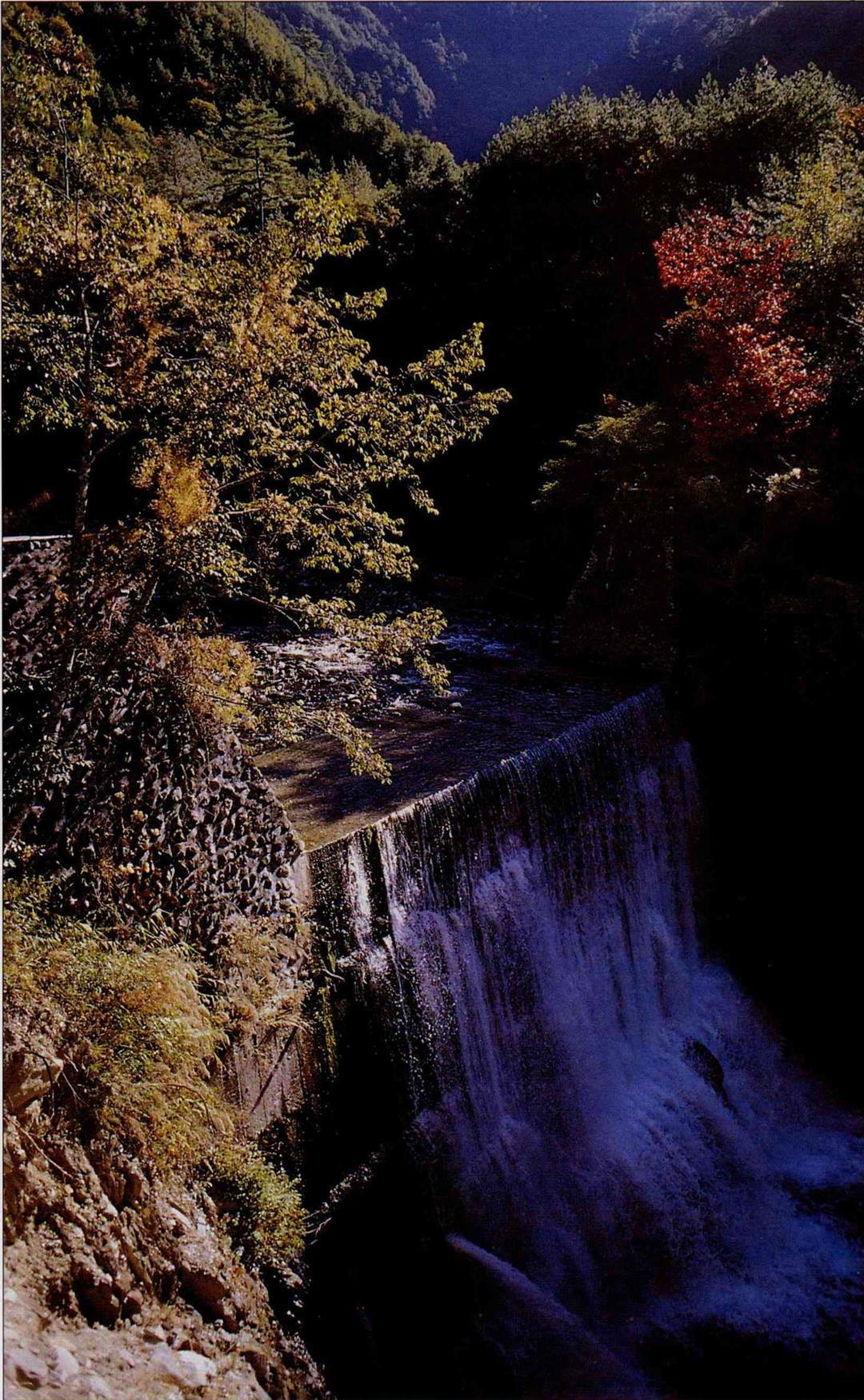

In the 1970s, with the development of the Taichung metropolitan area, many reservoirs were constructed in the Tachia River watershed. The river current became stagnant. The brook masu salmon, being selective about its environment, could not live in a waterway so lacking in vitality. Moreover, agricultural development along the banks of the river caused soil erosion and led to landslides, depositing large amounts of silt and rocks in the reservoirs. The authorities responded by building up sand retention dams. The river increasingly came to resemble a blocked digestive system. Over the years, soil and rocks have accumulated around the sand retention dams, making the river shallower and slowing the current.

Previously salmon had taken advantage of different types of topography to adapt to natural disasters. Today there are no pools for them to escape to, and when heavy rains come the fish are washed downstream. No fish, no matter how strong, can overcome the meters-high dams to get back upstream, so they are left to die from the higher water temperatures downstream.

For the Taiwan brook masu salmon, already landlocked and unable to interact with other groups of the same species, the subdivision of its living space by the sand retention dams means a further narrowing of the gene pool and a serious problem of inbreeding. In the past, the fish would do battle for mates, but today they don't even have to have an argument over it. Lacking competition, the remaining salmon grow less vigorous with each generation, and lose their resistance to disease. They are "fish out of water," unable to build up their defenses against modern civilization.

Although sand retention dams are devastating to the salmon, they cannot be removed carelessly, or a second disaster could result.

Forebodings of death

Thus various factors have combined to eliminate all the brook masu salmon except in a small segment of the Chichiawan Stream. But the deterioration of the environment is now being extended even to the Chichiawan, in which so many people place their hopes.

Like those able to foresee the deaths of others, the staff in charge of the restoration effort can only see the fish they have saved as creatures without a future.

"In fact, scholars are very clear that propagation can only treat the symptoms," says Chuang Ling-chuan, who has already turned to studying another fish species unique to Taiwan, the ku fish. Scholars can certainly achieve results in their breeding research simply by working harder, but the fate of the salmon will depend on more than their effort; it also involves overall policy decisions and coordination among many government agencies.

These coordination problems arise because, before the beginning of the restoration project, a number of units--including the Department of Forestry of the Taiwan Provincial Government (in charge of the forest), the Teh Chi Reservoir Management Commission (overseeing the water), and the Vocational Assistance Commission for Retired Servicemen (VACRS, which promotes high altitude agriculture in the area)--had some degree of control over the Chichiawan Stream area. The restoration program has run into thorny and complex problems because the work of each agency affects that of the other agencies.

The Department of Zoology at National Taiwan University demonstrated long ago that the Wuling Hotel, a 200-bed lodge located alongside the Chichiawan Stream and operated by the Department of Forestry, releases pollutants into the water. During the dry season, when there is not enough water to dilute the pollutants, they severely damage the water quality in Chichiawan Stream. Yet, after more than a decade, the Wuling Hotel has still not installed waste water treatment equipment.

The success of the restoration program cannot be judged by the number of fish alone. The by-product of environmental education is even more important in the long run. The photo is of Liao Man-ying, a guide at Shei-Pa National Park, explaining to visitors about the crisis faced by the salmon.

Planting the seeds of destruction

The Wuling Farm, which promotes high-altitude fruit and vegetable farming, and is also located next to the Chichiawan Stream, has long been criticized because its unrestrained exploitation of slope land has shortened the life expectancy of the reservoirs. But because VACRS operations are closely tied to the lives of military veterans, the problems caused by the farm have been difficult to resolve. After the Council of Agriculture listed the Chichiawan Stream as a protected ecological area, it was stipulated that no agricultural activity should be permitted within 30 meters of its banks. But VACRS, which runs the farm, has demanded a large amount of money to allow those now farming in the area to change professions. The impasse remains unresolved.

Though this is the most expensive species restoration program in Taiwan's history, compared to funding for other types of construction in Taiwan, conservation appropriations are grossly inadequate. Add to this that the agencies involved all look after their own priorities first, and the result is that the salmon restoration project can deal only with the symptoms, not the fundamental problems.

In the Japanese occupation era, there was a 300-meter wide protective belt on both sides of the river in order to insulate the river against manmade pollution. Today, orchards and rows of vegetable plants are less than 10 meters from the stream's edge.

These days, you can see mud pouring continuously from the cultivated land into both sides of the Chichiawan Stream. The water is filled with silt, greatly reducing the oxygen permeability. In addition, chemical fertilizers from the farm have caused an overgrowth in the algae on the rocks. As a consequence, both the rate at which eggs are produced and the rate at which the eggs hatch have been in decline.

Powerless

Since 1985, this most costly restoration project in the history of the Republic of China has produced seven specialists with doctorates or master's degrees, more than 20 studies, and the foundations for a biological data bank. How sad, then, that it will all prove useless so long as the changes in the environment continue unchecked.

"I have found out from this process that I am powerless to stop this disaster from happening. So when you ask about the fate of this fish, I more or less know what is coming," concludes Tai Yung-ti. He is grateful enough that today, only ten years after conservation was unknown to the general public, one could go to jail for catching protected fish, and he doesn't dare hope for too much all at once.

In fact, the problem of the salmon reflects the larger issue of inefficient use of land and water resources. Although every agency working in the Chichiawan Stream watershed has its particular mission to fulfill, use and management of the steep slopes along the upstream portion of the Chichiawan should not be overly diversified. This is because it is not the area with the highest economic output value. If efforts are made to simultaneously develop agriculture, recreation, and electricity generation, then the salmon must be sacrificed.

Wu Hsiang-chien, the chief of the Conservation Division at the Shei-Pa National Park, takes a different perspective in looking at the development of the Tachia River. "Even if there were no fish, it would still be necessary to halt development of the upstream portion of the Tachia River, because the river takes care of the two million people in the greater Taichung metropolitan area." The protection of the river, and of the salmon, will in the end most benefit people.

Fillet of soul

The Tachia River, flowing between blue skies and green peaks, is the water source for Taichung City. "The water the people of Taichung drink originates in the home of these fish, so there is a little of the soul of the salmon in every living being in Taichung," suggests James Wang, who is today an associate professor in the Graduate Institute of Environmental Education at National Normal University. If it is impossible for a few small fish to survive in the upstream portion of the river, this means that everyone's quality of life must be declining.

As with the air and water, the fate of the salmon is a symptom of the human quality of life. Only if the salmon is able to remain healthy and survive can the quality of human life be raised. Taiwan has already spent hundreds of millions of dollars cleaning up the downstream sections of many of its rivers. If it proves impossible to save the salmon, it will only be a matter of time before cleanup work will have to move up the mountains.

Today it is this precious national fish, tomorrow it will be another creature. If we allow our own rare species to pass away in this generation, then saving the rhino or the elephant will mean little more than good public relations work. Like a row of dominoes, Taiwan's own animals will fall one after another.

"After a decade of study, it is no longer a matter of theory for the salmon. The moment of decision-- life or death--is upon us," says James Wang, who is at once pessimistic and hopeful. This precious fish has survived countless disasters over a million years, but these few years will decide whether it can continue on. If the Chichiawan Stream is to be the fount of life for the salmon, the problem of development in the mountains must be resolved as quickly as possible.

Today the salmon, tomorrow the world

Today the salmon is in the "intensive care unit." Everyone must be patient, and reduce interference to a minimum. When conservation has proved successful, then further development can be discussed.

Wang, still refusing to admit defeat, says that if VACRS insists on getting its money before it stops cultivation in the area, then more money should be spent on behalf of the salmon. "What is it that Taiwan can be proud of? What do tourists come here to see? The Taiwan salmon, unique in the world, is indubitably of great value."

But he also knows that it will be very difficult for the salmon to recover, and that extraordinary measures are called for. Many people will have to appeal for its life. Only through policy changes and negotiations can the production situation along the banks of the river be altered.

Today restoration work is in its second decade. The salmon were the main reason for the establishment of the country's fifth national park (the Shei-Pa National Park) by the Ministry of the Interior.

National parks are founded for the purposes of conservation and environmental education. It is hoped that the management of the resources of the Tachia River can be simplified , with top priority being given to preserving the diversity of species, so that the Tachia River can begin to breathe easier and recover its strength.

The battle over the brook masu salmon is an important milestone in the history of ecological conservation in Taiwan. In this process the public, government agencies, and the environmentalist community are all learning the logic of sustainable development, and are coming to understand how to save a creature which is struggling on the edge of extinction.

"Although they have lived here much longer than we have, it is uncertain whether they will be able to survive us," says Wang. This is an issue that all the people of this piece of the earth must face.

The question is whether or not people will be able to clean up the mess we have created. Perhaps the salmon is the best chance to learn how.

[Picture Caption]

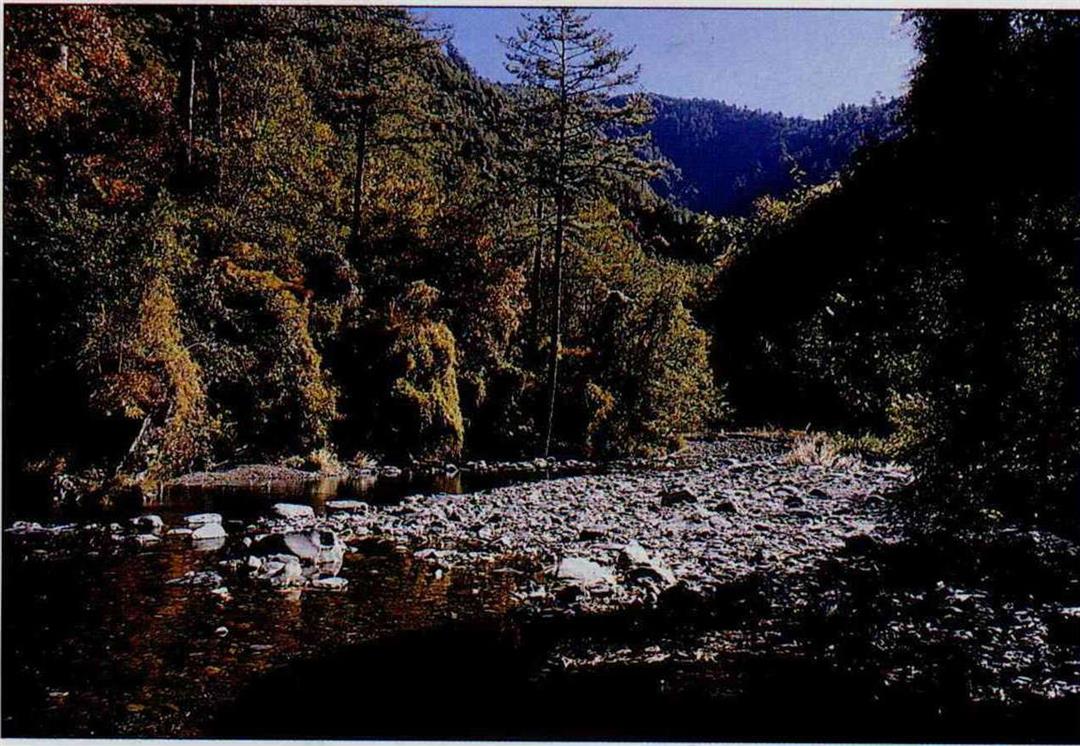

p.46

After ten years of restoration work, the academic community has accumulated a rich supply of information about the habitat of the brook masu salmon. But the habitat itself continues to deteriorate.

p.47

Lack of coordination among government units has made it difficult to improve the salmon's environment. Though beautiful, the fish faces an uncertain future. (photo courtesy of Shei-Pa National Park)

p.48

The brook masu salmon needs different types of habitats as it grows. Eggs are usually laid in places where the water is shallow and the current is gentle, where the eggs will sink easily and lodge between rocks. Fry, on the other hand, tend to select dark places, in order to avoid predators. (photo courtesy of Shei-Pa National Park)

p.50

The salmon has been a victim of high altitude agriculture. Yet people are even more the losers. (photo by Vincent Chang)

p.51

Although sand retention dams are devastating to the salmon, they cannot be removed carelessly, or a second disaster could result.

p.52

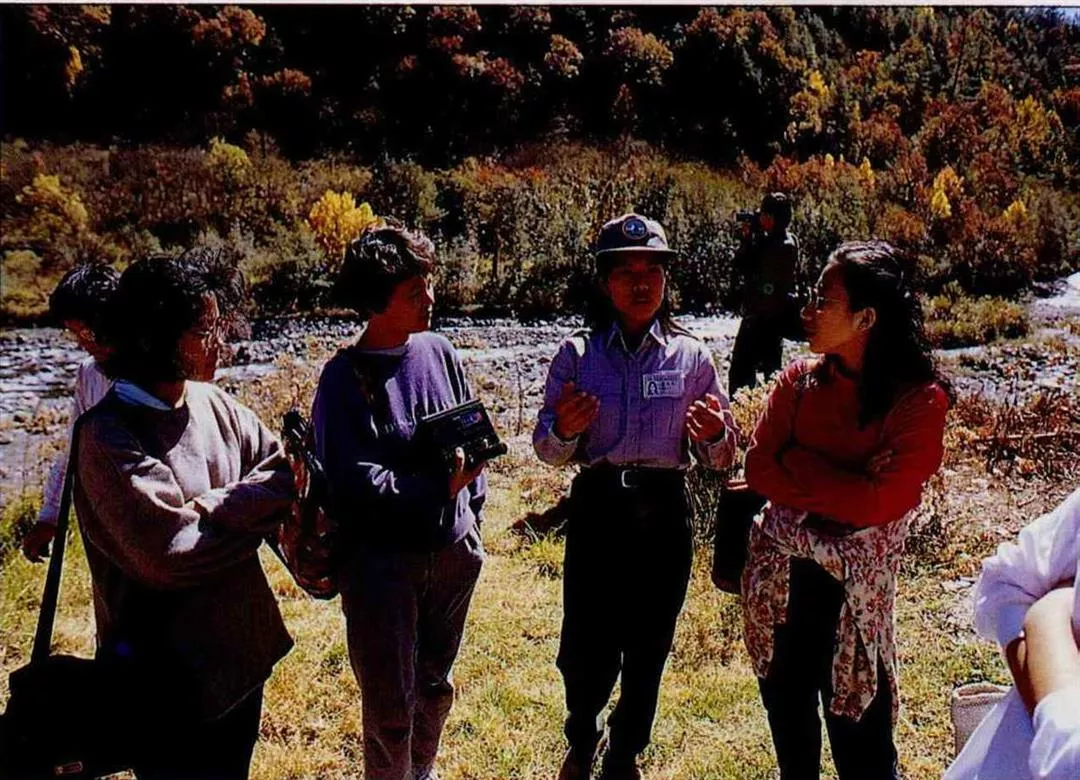

The success of the restoration program cannot be judged by the number of fish alone. The by-product of environmental education is even more important in the long run. The photo is of Liao Man-ying, a guide at Shei-Pa National Park, explaining to visitors about the crisis faced by the salmon.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)