The Dafen mountain area is located in the eastern part of Yushan National Park, in the middle reaches of the Lakulaku River. Though lacking both the imposing height and international renown of the main peak of Mt. Jade, Dafen has its own claims to fame. During the Japanese occupation era, it was the site of the famous armed resistance put up by the Bunun Aboriginal people against the Japanese. Moreover, here deep in the cloud-shrouded Central Mountain Range, because there are Japanese blue oak groves everywhere, Formosan black bears-who just love the acorns of the Japanese blue oak-gather here from all directions every winter when the acorns ripen to enjoy a big feast. Because black bears are ordinarily very reclusive, and it is very rare to see them in groups, Dafen has become a paradise for the study of the Formosan black bear.

However, Dafen is located in a high mountain valley right at the intersection of the southern and northern sections of the Central Mountain Range, at about the centermost point of the east-west trail that runs through the range at that latitude. There are few traces of human activity, and a one-way trip requires three days of hiking. Arranging the manpower, supplies, and financing are all problematic.

Twelve years ago, a tall and slender female research student-Hwang Mei-hsiu-nonetheless completed this mission impossible. With the help of Bunun indigenous people, she captured alive 15 black bears, and tagged them for follow-up research. After completing her PhD at the University of Minnesota in the US in 2003, Hwang returned to Taiwan to take up a teaching position in the Institute of Wildlife Conservation at National Pingtung University of Science and Technology. She has since continued to lead research teams to Dafen to study the ecology, genetics, and other aspects of black bears. In recent years her work has extended to surveying the distribution of these creatures across all of Taiwan, slowly piecing together the way Formosan black bears live, in an effort to find a road to survival for this endangered species.

The only way to get into the Dafen mountain area is via the eastern section of the Japanese-era Batongguan Trail; it's 40 kilometers from the trailhead to Dafen. On the fourth day of the Chinese New Year holiday, journalists from Taiwan Panorama accompanied Hwang Mei-hsiu's research team as they departed from the Nan'an trailhead in Zhuolu Township, Hualien County. The seven team members shared out the research equipment and 10 days of supplies, with each person packing 20 to 30 kilograms on their back, as the three-day journey into the mountains got underway.

The first 13 kilometers of the old Japanese trail, which follows the winding path of the Lakulaku River, are open to ordinary travelers, and we passed many vacationing hikers along the way, exchanging traditional New Year greetings. The waterfalls and fern plants along the way were reminiscent of Jurassic Park. Once you pass Walami Cabin, you enter the ecological conservation zone. Here there are few signs of human activity. From time to time we were driven to distraction by the "biting cats" (stinging nettles) and tick-trefoil, but the skeletons of the hickory trees, with all their leaves fallen to the ground, standing amidst the cloudy mist, lent a certain poeticism to the path.

The more deeply we penetrated the mountains, the more signs there were of wildlife. The feces of mountain goats, like black pearls, with more than 100 pellets to a pile, were often sighted along the roadside, while oval-shaped feces of sambar and muntjac were scattered about like coffee beans.

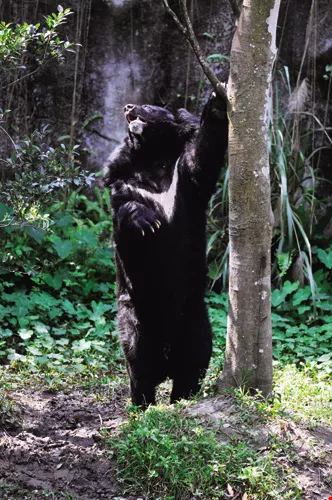

The Formosan black bear, black from head to toe except for V-shaped markings on the chest, is a Taiwanese subspecies of the Asian black bear. It is the largest living land animal of the order Carnivora in Taiwan.

Our three-day journey, with the drizzle interrupted only by pouring rain, is taken at a slow walk. Enveloped in mountain mists, even when it is only raining lightly your whole body, encased in raingear, is soaked through. Though it is not cold when you are walking, as soon as you put down the backpack for a rest or lunch, you find yourself starting to shiver after just a few minutes. All you can do is catch your breath for a few moments then hit the trail again.

The second day, sitting in the shadow of the mountains under a very basic canvas tent munching on bread, Hwang Mei-hsiu recalls a time when they were coming back down the mountains and reached this place cold and wet in the darkness. One team member was too exhausted to go on, so they changed their original plan of spending the night in Walami Cabin, and decided to stay here. Unfortunately, the rice they had "hidden" here on the way up the mountain was gone (they assumed that workers on some project had eaten it all up), so the seven or eight of them had to endure a very hungry night on just one pot of mushroom soup. To top it all off, during the night wind blew the rain in from all directions, and they were virtually "steeped" in water under their canvas like leaves in a teabag.

The third day of our journey up the trail, we passed by Duomeili, the site of a former Japanese police outpost. The impressive walls made of piled-up flagstones, surrounded by ancient trees, evoked a time long gone... but sadly we were too overcome by wetness and exhaustion to really appreciate it. When we later crossed a steel suspension bridge, Hwang pointed to the remnants of a wooden bridge hung below, and talked about how they used to cross that bridge, which was covered in moss and rotten in places, with just a few none-too-dependable-looking steel cables holding the thing precariously up-each step was an act of daring. In those days you had to cross several dangerous bridges much like it. Some had no wooden planks at all, leaving the research team members to tiptoe across rusty steel cables like high-wire performers in a circus, while far below was deep fast-running water.

Today, thanks to the years of effort put in by the Yushan National Park authorities, the current trail to Dafen seems like a piece of cake to Hwang. Small wonder that she described the hike on the third day, which turned out to be a major test for the journalists and volunteers, as merely "a little bit harder than the rest." On the third day, because one section of the Japanese cross-mountain trail was wiped out by a huge landslide, we had to go straight over a mountaintop, followed by a steeply sloping descent of 1000 meters. The path was uneven and slippery, and after three or four hours it became a challenge to decide if we were more wet or more exhausted, until each step became a struggle. After crossing the river valley at the bottom, it was back up a hill, so steep that we had to pull ourselves up with the rope that is left permanently there, and it was only when we reached the ridgeline of that rise that we finally saw Dafen Cabin-albeit on the opposite slope! At least at that point we could get back on the relatively smooth Japanese-era trail, and after another hour winding around a mountain, we finally reached Dafen.

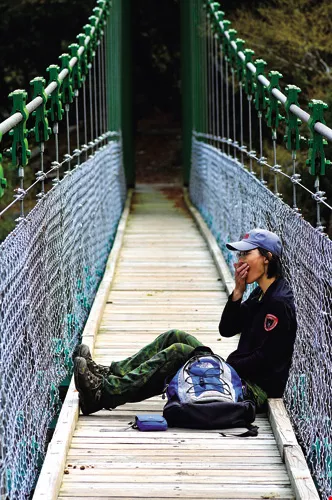

After a whole day trekking through wilderness, on the way back from Saike to Dafen Hwang Mei-hsiu sits on the Dafen suspension bridge and scarfs down a snack to bolster her energy level.

Hwang's students and volunteers have since last October made this journey across mountains and rivers to the Dafen area once a month, or five times in all. Going all the way back to 2006, when the Yushan National Park Headquarters commissioned the black bear research program, this marks the fifth year of struggling up to Dafen.

Hwang's fateful connection with Dafen dates back to her PhD dissertation. When she went to the US in 1996 to begin her doctoral studies, she originally thought to continue working on the subject of her MA thesis: the crab-eating mongoose. But because she came to admire the work of the ursologist David Garshelis, she suddenly decided to become his student and thrust herself body and soul into the very difficult field of bear research.

At that time there was very little knowledge about the black bear among academics in Taiwan. Wang Ying of the Department of Life Science at National Taiwan Normal University had done a preliminary survey of the distribution of black bears across the island, but that was about it. There wasn't even any basic data about the habits of black bears or their numbers.

In order to better understand the habits and range of black bears in the wild, it was necessary to do traditional trapping and tagging. After returning to Taiwan for her doctoral research, Hwang put out bear bait in more than 60 locations on Mt. Lala and Mt. Chuyun and in Yushan National Park where black bears were most likely to appear. The place with the most bears would be the place where she would do the actual trapping. Unfortunately, virtually all of the bait went untouched; the only place where there were claw marks was on a tree on the way to Walami in the Yushan National Park.

Later on, when interviewing Bunun hunters, she found that they all had the same advice: "If you want to trap bears, go to Dafen." They knew that the bears congregate there every winter to eat the acorns of the Japanese blue oak. Hwang then visited the site herself and discovered bear feces, claw marks, footprints, and other signs. So she steeled herself to working in Dafen, a place that the academic community had previously seen as too forbidding to venture into.

During more than two years of research, working with Bunun people and national park ranger Lin Yuan-yuan, they set up many traps, and trapped 15 black bears, far exceeding their expectations.

Hwang recalls the situation the very first time they trapped a bear: It was pouring with rain, the bear was roaring and struggling, and the blow darts with the anesthetic either didn't hit the mark or were shaken off by the bear. After their second and third bears, they gradually got more practiced at doping their subjects, but it was still necessary to accurately insert the anesthetic with the bear right up in your face, and then rapidly complete weighing and measuring, taking a blood sample, inserting a chip, attaching a transmitter, and other tasks. Even then, the process was not considered to be a success until the team, hidden not far away, confirmed that the bear had safely walked away.

And that was just the preliminaries! After attaching wireless transmitters on one bear after another, Hwang and her volunteers then had to undertake the long and patient mission of "bear tracking" deep in the mountains.

Where there's no trail, climb; where there's no bridge, wade-this is how Hwang Mei-hsiu and her team have sharpened their wilderness skills and endurance.

"Every time you track a bear you need two teams, in two different positions, each with a wireless receiver to search for the transmitter signal," explains Hwang. When the animal is active, the receiver gets a rapid beep-beep sound, but when the animal is stationary the beeping will slow down and stabilize. However, receiving the signal only tells you the direction of the animal's activity. You have to have two receivers getting a signal from the same bear simultaneously, and then you have to find the intersection of the directional lines on a map to determine the bear's position (this is called triangulation).

Mountain topography is complex, and the wireless signal can be cut off by undulations in the terrain, causing frequent misjudgments as to direction. Or it often happens that the two signal directions are dissimilar, or that an intersection point cannot be found. Or one second the receiver is getting a signal as clear as if the bear were within arm's length, but the next second, as the creature crosses the crest of a ridge, the signal virtually disappears. This game of hide and seek deep in the mountains can be exhausting, frustrating, and infuriating for the research teams.

After more than two years of dogged tracking, they were able to come up with an outline of the activity of Yushan black bears. The bears spend about 54-57% of each day in active mode. They are mainly active during daylight hours. But during the fall and winter when the acorns and nuts ripen on trees of the family Fagaceae (of which the Japanese blue oak is one) in large amounts, in order to take in more food, the bears also become "night owls." (Unlike temperate-zone bears, Formosan black bears do not hibernate in winter.)

The majority of bear activity occurs between 1000 and 2500 meters altitude. The range of activity of any individual bear is roughly 30 to 100 square kilometers, though a few reach as high as 200 square kilometers (or one fifth of the area of Yushan National Park). About half of the bears left the area of the park at some point, exposing themselves to risk outside the protected zone. At the same time, the researchers found that black bears do not, as Aboriginal sources suggested, all move to lower altitude areas or return to the Dafen area during winter. In addition to seasonal factors, their range of activity is also clearly related to food availability, mating, and human activity.

Most worrisome is that, "of the 15 bears that we tagged," says Hwang, "two of them had lost a paw and six others had lost toes, meaning that the injury rate was 53%!" If over half of the bears deep in the Central Mountain Range and moreover inside a national park (i.e. a relatively well managed area in terms of conservation) have limb injuries, who knows how many black bears in other areas die in traps.

Hwang relates: "Illegal hunting is currently the greatest threat to the black bear, with the damage caused being much greater than from shrinking of its habitat." In fact, Aboriginal people aren't deliberately hunting bears (the bears are generally caught in traps made for other animals), so the authorities should make more effort to involve them in future bear conservation measures. (See p. 89.)

For the five days that the research team spent in Dafen, work was divided up and people were dispatched near and far to do surveys. The route to Saike (to the south) is very rugged, without even a simple path, so skilled veterans like Lin Kuan-fu are needed to lead the way.

As the tagging research on Yushan black bears reached a certain point, new questions arose. What is the total black bear population in Yushan? Is there a risk of excessive inbreeding if the population is too small? What methods could be used to track rises and falls in the population and give off warning signals? The fact that so many mysteries remain unsolved is the reason why Hwang has continued to stay locked on to Dafen for research.

"Since beginning surveys of the Dafen area in 2006, when we were commissioned to do so by the Yushan National Park, there has been a direct correlation between the number of acorns and black bear activity," states Hwang. After four years of surveys, they have discovered that in years when the oaks produce more acorns, not only does the number of bears that appear increase, the food also attracts other large mammals like boar, goats, and sambar. "The impact is far greater than we had assumed." In 2008, when there was peak acorn production, 60 or 70 bears showed up to join in the feast! Based on this she surmises that the resident bear population in Yushan National Park is between 50 and 150.

Because the black bears stay close when food is plentiful, when acorns are in short supply they are more likely to wander outside the national park to search for sustenance. Therefore, if researchers can discover any cyclical pattern in the Japanese blue oak (as has been done in Japan, where there is a peak in acorn production every six or seven years), then in periods of shortfall, they can recommend that the park authorities increase patrols along the park's borders to reduce the likelihood of bears "crossing the line" and getting caught in traps.

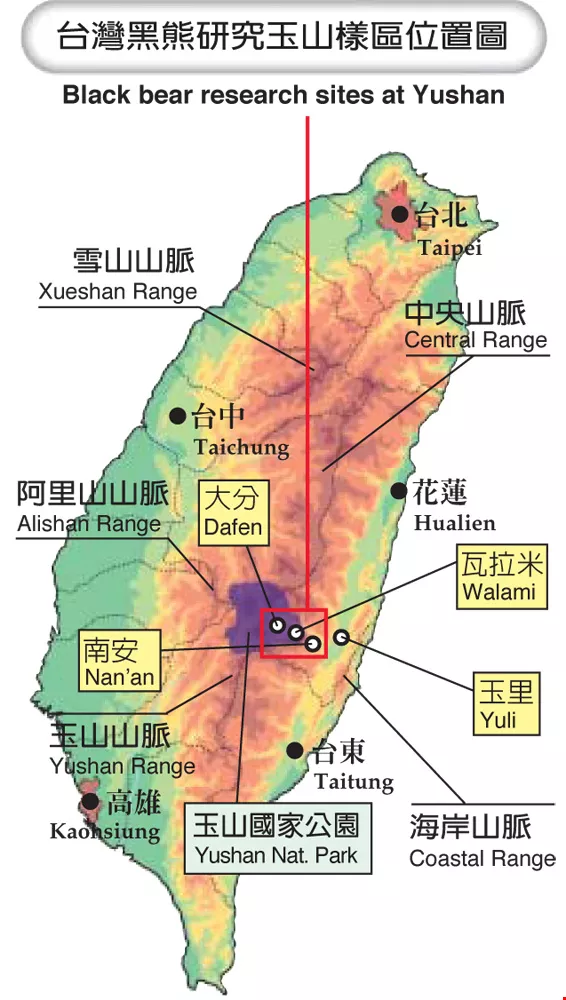

Black bear research sites at Yushan

Hwang says, "It is so difficult just to come up here that we try to collect as many different kinds of data at the same time as we can." Besides gathering long-term data and calculating the number of acorns in each year, they also collect three other sets of info: statistics on bear hairs, feces, and claw marks in the oak trees. These basic numbers are collected once a month during the acorn ripening season (October to January). The research team has laid out eight "transects" (essentially fixed paths in the woods) at different altitudes and terrain for routine surveys (each transect being 200 to 1000 meters long), and data is collected on these in a regular sequence.

At just after seven in the morning on our second day in Dafen, everyone is already in place when we come to the first transect, which is about 500 meters long. All I can see is that one or two nets have been hung between two trees every 50 meters as "seed traps" (each trap surveys one sample tree). Volunteers first count the number of acorns in each net, and after placing the acorns into a sealable plastic bag, bend over to count the number of fallen acorns on the ground within one meter of each sample tree, in order to learn how many fallen acorns are eaten by animals. Another group, led by Hwang and a graduate student, goes along the transect to look for broken branches, bear claw marks, and feces. "The usual habit of the black bear is to climb into the tree while picking and eating the acorns all around." By the time this survey of 20 nets and traces of bear activity is finished, noon has snuck up on us.

Data are collected on two transects during this day. This same night, six feces samples are placed separately into alcohol (for later DNA analysis) or formalin (for parasite analysis), or put into sealable plastic bags (for food analysis). Each is assigned a number and details-including whether the feces is fresh or not, the location found, the surroundings, and the type of food found in the feces-are meticulously recorded in a notebook. Claw marks and bear hairs also have to be individually numbered and recorded. When the recording process is finished, there is a meeting to review the day's work and discuss the next day's itinerary. It is already late at night when this meeting finishes.

Hwang Mei-hsiu says that some of the data collected still has not been analyzed, and will only become useful when follow-up funding becomes available or related research projects are done in the future. For example, last year funding was received to do very expensive DNA analysis. From the DNA in feces it was discovered that the genetic diversity among Yushan black bears is still quite good, so there is likely no immediate species endangerment from inbreeding. But whether the black bear population can be sustained is also connected to whether or not there is compartmentalization separating the genes of the Yushan population from those of Xueshan, Lalashan, and other areas. The basic data collected from Yushan bears can be kept in reserve to help answer this question in future.

This pile of bear feces sitting amidst pine needles is a month or two old.

The afternoon of the second day in Dafen, someone discovers the still fresh carcass of a sambar. Hwang immediately brings the team forward to put up "bear hair traps" (generally using odorant as bait to attract the bears and collect some of their coat hairs) and an automated camera. Hwang and the students deftly put up, at a radius of five meters from the carcass, two barbed wires strung across four trees at heights of 20 and 50 centimeters above the ground. "This way, in addition to getting hair samples, we will be able to see how many bears come to share the carcass, and also photograph how the bears (or other animals) get past the metal wire trap, in order to understand more kinds of behavior."

In the dense forest, there is close interaction between plant and animal life, which could be another factor affecting black bear populations. Just as the cyclical changes in the number of acorns will affect the populations of black bears and other large mammals, the team asks: What has been the effect on black bears of the rise in the sambar population over the last 10 years? Will these deer-like creatures, who love the bark of cherry trees so much that they actually eat the trees to death, compete with the bears for food? Why has there been an increase in the number of sambar carcasses this year? What has been the impact on bears? The complexity of ecological phenomena means that such questions can only be answered through complementary work in many academic fields.

"Unfortunately, despite the fact that Dafen is a paradise for research on wild plants and animals, it is asking a lot to hope that other teams will come here to do research." Hwang points out that the round-trip journey alone takes up seven days, so that besides the extreme physical tests and the isolation and difficulty of the environment, there is also an investment of time. How many researchers are willing to accept such a "low return on investment"?

Once she faced up to the practical limitations, Hwang changed her research strategy. "It doesn't matter if no one else comes up here for research. I'll have the data and interesting subjects to explore and then everyone can contribute." For example, her materials could lead to further research on bear epidemiology or biology-if enough feces can be collected, the chances for cooperative work with researchers in such fields will greatly increase.

After discovering a dead sambar, researchers immediately set up a barbed-wire perimeter around the carcass as well as an automatic camera to capture images of how black bears get past the wire, and to observe how many animals will come for a share of the food.

Ever since Hwang began her research trapping and tagging bears, she has gotten a lot of media attention. There has been a stream of television and newspaper reports on Formosan black bears and on this "Mama Bear" and her adventures. Also, national parks and forestry agencies have provided her with a series of grants to carry on related research. But behind this apparent success story, there is another side: a chronic shortage of funds and a lack of consistency in staffing.

In terms of government funding, most grants are restricted to NT$1 million over one year, with a limit of one research assistant. "Government agencies, it seems, have never considered that field research may require a whole team to be done properly," says Hwang. Therefore she must resort to organizing her own students, students from other departments to whom she is a co-advisor, and volunteers to form research teams in order to keep the work of collecting data in Dafen uninterrupted.

Besides funding problems, "You have to try to figure out how to retain students," says Hwang. A student will have to spend an extra year or two in school if he or she wants to research black bears as compared to studying smaller animals, so the field is at an innate disadvantage. Then you add in the hardships of the fieldwork-for example, graduate student Lin Kuan-fu, who is working with Hwang, has been to Dafen 23 times over the past two years and in autumn and winter spends half his life in the forest-it is hard for students to stay the course unless they have exceptional interest and determination.

"The safety of the students is an even bigger concern." Hwang recalls one incident that occurred during Typhoon Morakot last year. Three students were in the third day of their journey to Dafen, and one of them, a girl in the veterinary medicine department, was already exhausted by the time they got to Duomeili. The team leader wanted to make a dash for Dafen Cabin, the best-equipped place to ride out the storm. But unfortunately the girl had become increasingly fearful after walking several cliff paths, and she couldn't go on. The team leader, who hadn't even noticed this problem, much less dealt with it in a timely way, had no idea what to do, and called Hwang on the satellite phone for help. "I had to virtually scream at him to pull the team back to the shelter of the previous stop!" Hwang says the team needed to stick together, and moreover that to get to Dafen they would have had to cross another river. If the typhoon had caused a flash flood, the consequences would have been unthinkable.

Young volunteers delightedly expressed their admiration for the skill shown by Lin Yuan-yuan (right) in starting and tending a campfire.

Hwang sighs, "Sometimes I ask myself why I am so foolish-it's one thing to make life hard for myself, but why do I have to recruit students who I'll then have to worry about?" Calculated at two graduate student recruits per year plus one research assistant, over 20 years of teaching she will have put more than 60 lives at risk in the mountains. She loses as much sleep over this as she does over the fate of the endangered black bears.

But the experiences of students are not nearly as frightful as those Hwang has faced herself. In a book recording her field research, there are many instances of typhoons, of research stations being attacked by bears, of stings by hornets and such that are so painful a whole night of sleep is lost, of trying to track the elusive bears in rain and mountain fogs.... Her experiences have been worthy of the hardiest frontiersman or adventurer.

On this reporter's trip back down the mountain, Lin Yuan-yuan, the same person who helped Hwang trap the bears back when, recalls a time when Mei-hsiu's soul was very nearly separated from her body: At that time Lin and Hwang were walking along a big cliff, and Hwang was hit by a falling rock that had been loosened by a just-passed typhoon. As she slipped down the almost vertical slope, Lin, crouching on top of the cliff, grabbed hold of her. Hwang frantically fought for a foothold on the mountain wall, but rock fragments just sharded off and she couldn't get a grip. After the two had struggled for a long time, and neither could go on much longer, Hwang called out: "Let go, my friend. You have a wife and child!" But Lin, whose sense of duty to a friend is profound, refused to loosen his grip, and in his heart kept calling on his ancestors for help, until finally-literally on the brink of death-Hwang's foot landed on a solid piece of earth and her life was saved.

Looking back at the many near-misses suffered by Hwang and her team over the past decade-plus, could it be that Heaven is looking after this "Mama Bear" who holds nothing back and is willing to face death on behalf of black bears? At the very least, it is certain that some Aboriginal people have given up hunting bear out of respect for "this woman who is really facing hardships in the mountains trying to find bears," and the Taiwanese public, thanks to increased understanding and awareness of the black bear, has taken a further step in accepting conservation.

Over the past five years, Hwang has extended the scope of her research beyond Dafen, and is taking on the even more daunting task of an island-wide survey. Surveys in mountain forests that don't even have old trails suggest that the situation is not good (Taiwan's total black bear population is estimated at 300-800), and you can see many traps spread out over the mountains. When you also consider that habitat areas are being sliced up by roads, so that bears in the coastal mountains and those in the Central Mountain Range cannot interbreed, the possibility that these creatures will become extinct is exacerbated.

Do the black bears of Yushan-these sacred symbols of the "Jade Mountain" which is itself a sacred symbol of Taiwan-have a future? The only way to find the answer will be to do continuous research of even broader scope. Facing uncertainties over funding and manpower, Hwang Mei-hsiu is relying on her undiminished passion and tenacity to try to save the black bears. She doesn't want your applause, she just wants more people to show some concern for the future of endangered species.

The sun finally came out on our second day in Dafen, and everyone hung out their wet clothes to dry.

To get from the trailhead to Dafen, the main area of black bear research, takes three days of hiking with a heavy pack on your back. Our three-day-plus journey was mostly conducted in mist and rain, with everyone soaked and tired.

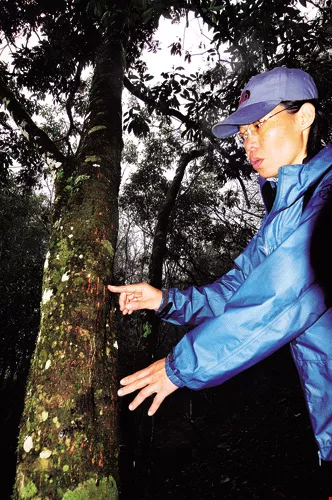

It is not that hard in Dafen to find claw marks left by black bears climbing into trees. Hwang Mei-hsiu explains that this reddish color indicates that the mark is fresh, with the marks becoming darker as time passes.

The mid-altitude zones of the misty Central Mountain Range are the main areas of activity of Taiwan's black bears. "Mama Bear" Hwang Mei-hsiu (center foreground) has been doing field research in these remote forests for many years. She has gotten a lot of public attention, despite her modest and camera-shy personality.

Hwang Mei-hsiu picks up a fallen acorn from the ground and breaks it open to show us the meat inside. This is the black bear's favorite food.