The Changing Face of the Lunar New Year

Lin Hsin-ching / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Scott Williams

February 2011

Whether living in Taiwan, mainland China, or elsewhere, ethnic Chinese around the world agree that the Lunar New Year was the most important holiday of our agrarian past, a time for replacing the old with the new, thanking Heaven, and getting together with family.

But critiques that the holiday "doesn't feel like the New Year's of old" and that it is even "annoying and dreaded" have begun to replace the boisterousness and sense of busy anticipation of yore.

People today seem to agree that the holiday "feels less and less like 'New Year's.'" Certainly, the Lunar New Year has changed. Commercial manipulation, social change, and the attenuation of familial relationships have all contributed to making it a quieter holiday. There's also been a complex shift in the psychology of the holiday.

In the hours before the clock struck 2011, a warm, festive atmosphere blanketed the whole of Taiwan as 53 New Year's events kicked off around the island, from the streets of Taipei to the slopes of Mt. Ali, from the northeast tip of the island to Orchid Island and the beaches of Kenting. An estimated 1.74 million people gathered in the chilly winter air, braving temperatures of just 5°C to count the seconds until 2011, send the old year on its way, and welcome in the new.

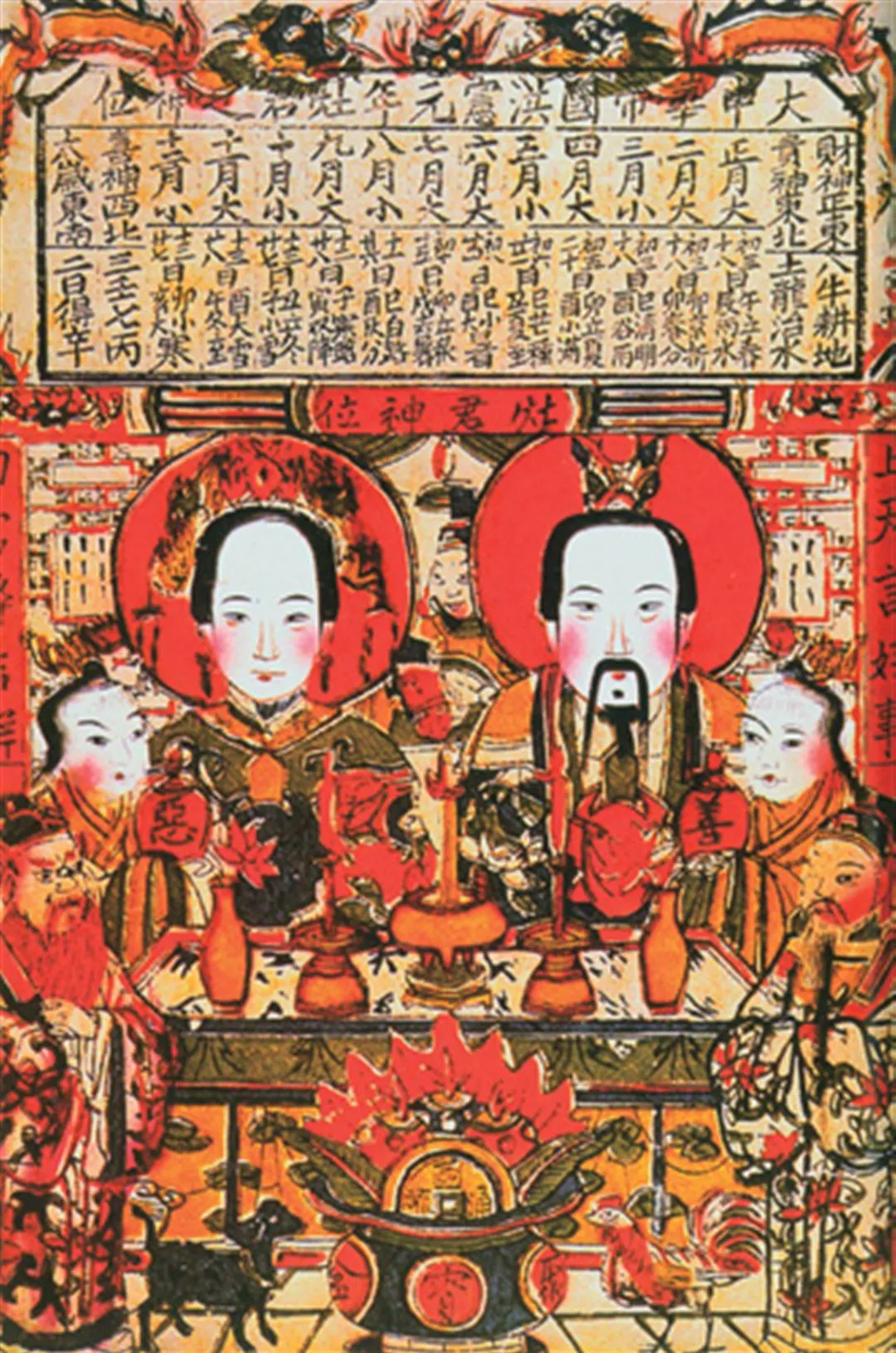

Traditionally, the Lunar New Year's festivities begin on the eighth day of the 12th month of the lunar calendar. The 16th and the 24th are also important days for feasting and making offerings. The festive atmosphere lasts at least until the Lantern Festival, which occurs on the 15th day of the first month of the new year. The photo shows a woodblock print of the Kitchen God and the Kitchen God's wife.

Taiwan has enjoyed these kinds of big, national celebrations of the arrival of the Western-calendar New Year for only a decade or so.

Taipei paved the way to them in 1995, during the tenure of Chen Shui-bian as mayor, when it held its first city-sponsored New Year's Eve event. It cleared the plaza in front of City Hall and invited citizens to count down to the New Year with pop stars and other performers. The event was a great success and received such widespread acclaim that city and county governments around the island began emulating it. Such New Year's gatherings have evolved since then and are now as entrenched in local customs as the barbeques of the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Meanwhile, the Lunar New Year, a holiday deeply connected with Chinese cultural values, has somehow come to elicit laments that it no longer means what it once did.

A few years ago Lan Pei-chia, an assistant professor with National Taiwan University's Department of Sociology, began wondering if other people disliked the Lunar New Year as much as she did. Many of us can surely relate. Lan's studies revealed that men don't like the Lunar New Year because giving holiday money in red envelopes to family members is expensive, but the act represents a performance of their social roles as fathers and sons. In addition, they have to participate in conversations about the size of annual bo-nuses that come up casually over games of mah-jong, and feel that this part of the Lunar New Year's experience subtly reflects on their performance at work and even their manliness.

Women, on the other hand, dislike the Lunar New Year because "spring cleaning" and preparing large holiday meals are heavy burdens that leave them even busier than normal in the run-up to the holiday. In addition, they have to play the daughter-in-law during the obligatory holiday visit to their husband's home, increasing the risk that latent mother/daughter-in-law and family conflicts will rear their heads.

"Singles also dislike the Lunar New Year, especially those whose parents have passed away or whose parents live with siblings," says Lan. "Where to spend the holiday is an awkward question for them. The prospect of friends and family asking them at get-togethers when they plan to get married is a source of anxiety and stress."

In addition, gay individuals who don't necessarily fit into the heterosexual family structure, single parents, and financially straitened families, as well as new immigrants unable to visit their natal families, are all likely to feel uncomfortable with the holiday's assumptions about family hier-archy, social relationships, and family reunions.

The central and southern parts of Taiwan, with their large farming populations and traditional clans, have a more festive New Year atmosphere than the north. In the photo, Lugang Township, Changhua County, joyously welcomes in the New Year with lanterns.

Cost is also an issue. There's a Cantonese saying that runs, "Rich people celebrate the Lunar New Year. The poor survive it." Getting through the holiday represents a real challenge to disadvantaged families. Chen Peiru, secretary-general of Taiwan Lifeline International, says that the number of people calling the group's 1995 hotline during the two months leading up to the Lunar New Year has been growing slightly every year. The majority want help with the economic and human sides of the holiday. The burden the holiday puts on family finances is frequently a source of profound fear and anxiety.

Prior to the start of the Lunar New Year in 2009, the Child Welfare League conducted a survey of nearly 800 disadvantaged families it serves. The results showed that 66% were experiencing a "moneyless Lunar New Year holiday." And some 20% had had their financial circumstances worsened further by the death, departure, serious illness or incarceration of the family's primary provider, making the holiday's traditional family gathering an impossibility.

Wang Yu-min, the league's executive director, says that the New Year's customs most of us take for granted-wearing new clothing, receiving a red envelope, and laying out a bountiful holiday meal-are luxuries beyond the reach of these families. "The celebratory atmosphere of the New Year that fills the streets can all too easily lead those who don't share in the good fortune to wonder why they suffer so and sometimes even cause them to take their own lives."

Wang says that several years ago, when the Taiwanese economy was in a rut, there was a rash of suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning among the unemployed and disadvantaged. Thereafter, several charities, the league among them, began providing Lunar New Year's meals and red envelopes to families in difficult circumstances to enable them to pass the holiday with greater peace of mind.

Paul Shiao, head of social services at the Taiwan Fund for Children and Families, stresses that families that suffer unexpected traumas such as the loss of a job, a divorce, or the death of a loved one aren't targeted for government or charitable services. Given that it's especially easy to feel down over the Lunar New Year holiday, people have to turn to family, friends, or even neighbors for support if they are to pull through.

Members of Taiwan's gay community don't like the odd looks they get at family gatherings. "Madame Yu," owner of Ximending's Hanshi Sauna, shares a little seasonal cheer with an annual Lunar New Year's Eve banquet for those who can't go home for the holidays.

Our endless chains of interpersonal relationships are another reason people don't much enjoy the Lunar New Year. In fact, mainland China has seen the emergence of a new word in recent years: kongguizu, those who fear returning home. The media has even gone so far as to delineate this group's five fears: "fear of the dinner-party merry-go-round," "fear of the spring rush" (a reference to the mobbed transportation system), "fear of parental pressures to marry," "fear of social obligations," and "fear of the post-holiday hangover."

Mainland China and Taiwan differ in many respects, but intensely interconnected social networks are a point of similarity among ethnic-Chinese communities the world over. It's therefore not surprising that many Taiwanese share the anxieties of the kongguizu. It's easy to imagine heightened mother/daughter-in-law tensions and greater numbers of marital spats during the long holiday, which leaves us with nowhere to hide from family gatherings. Taiwanese also have to deal with the pressure to marry and produce offspring, as well as the one-upmanship between siblings and in-laws in conversations about work, social standing, income, and their children's achievements.

A Ms. Huang says she experienced just such an awkward situation one New Year. Her husband was out of the country on business and, with money a little tight, she had only put a few thousand NT dollars in the red envelope for her mother-in-law. She didn't know that her husband's younger sister and husband would be coming back to Taiwan from their home abroad, bringing with them a red envelope stuffed with NT$120,000. "It was very embarrassing," she says. "The red envelope I'd prepared was so thin in comparison that I just couldn't give it to her. I held onto it rather than have my mother-in-law compare it to theirs and make me feel worse."

Taiwan's own well known Mama Jan Matchmaking says that in the few months prior to every Lunar New Year, the number of "prospective spouse meetings" between its members jumps by 20% to as many as 400 per month. Zhu Lili, who runs Mama Jan, says that singles often become the focus of attention at family gatherings dominated by couples, and that women face even greater pressure to marry than men, especially those in the 28-35 age range. At the outset, friends and family may urge them not to be "too picky," before moving on to the more pointed reminder that "when women get older, they can no longer have children and nobody wants them anymore." Men, on the other hand, are chided for being "unfilial" if they haven't married and had children. These pressures are what lead to Taiwan's pre-Lunar-New-Year rush to meet with prospective spouses and the mainland's "rent a spouse for the Lunar New Year" phenomenon.

A "gradual loss of meaning" has also contributed to the declining interest in the Lunar New Year.

For many, the Lunar New Year has long since ceased to be much more than a long holiday.

According to Cai Ying, who manages Danshui's Qifu Baosheng Shrine and has studied traditional New Year's customs extensively, the Lunar New Year knits the customs of agrarian society together with Confucian ethics. For example, making offerings to the gods and one's ancestors reaffirms the relationship between the gods and hu-man-ity to ensure the blessings of the gods on the coming year's harvest. The younger generation's paying of respect to their elders and the older generation's gifts of red envelopes to the younger reaffirm the generational hierarchy and filial values. The exceptionally rich New Year's feast and the custom of wearing new clothing serve as a counterpoint to the backbreaking labor and frugality of everyday life.

With Taiwan's transition from an agrarian to an industrial society, its people became much wealthier and a large number of once-beloved holiday rituals ceased to be special.

Take the customs of wearing new clothing and receiving red envelopes, for example. In leaner times, children naturally looked forward to such gifts. But today the majority of children have new clothes and pocket money aplenty, and are therefore much less excited by the prospect of New Year's gifts.

Similarly, to the busy, overfed people of the modern era the bountiful Lunar New Year's Eve feast is more negative than positive from the standpoints of both time and health. "Who's going to be excited about the delicacies on offer at the Lunar New Year when they're eating big meals the whole year round?" asks Cai Ying.

The modern diversity of family structures has also served to raise doubts about the meaning and form of the traditionally obligatory family gathering. Wendy Shieh, the head of Shih Chien University's Department of Social Work, says that though the majority of Taiwanese families are currently nuclear families, we also have growing numbers of single-parent families, couples cohabiting without marriage, homosexual couples, and even households comprised of couples with children from previous relationships. Singles living alone or with a pet constitute yet another type of "family" that has arisen in recent years.

With the evolution of these trends, people are wondering who, besides their parents and siblings, counts as family. They are also asking themselves who they really want to celebrate the holiday with and what kind of get-together they want to have. In the modern era, people can't help but revisit these kinds of questions as the holiday approaches.

For example, whose family should a gay couple or an unmarried-but-cohabiting heterosexual couple spend their Lunar New Year's Eve with? Should they visit both families? Should they face together the pressures to marry and uncomfortable looks that are part and parcel of family gatherings?

As Taiwan's gay community has come to put it: "You can hide during the Mid-Autumn Festival, but you can't hide on the Lunar New Year." Chien Chih-chieh, secretary-general of the Awakening Foundation, a proponent of both the proposed Spouse Act and the proposed Gay Marriage Act, notes that whether out of the closet or not, the compulsion to visit family at the New Year brings a lot of stress. Those still in the closet are likely to worry that they will be "outed," while those who are already out worry that their "difference" will cause talk among friends and family.

"The New Year also requires people to spend time away from their partners. As a consequence, not only do gay persons not get to enjoy the -friendly interactions associated with the New Year, they must also suffer the absence of their partners."

Chien adds that the phenomenon of gay people fearing family gatherings isn't limited to Taiwan. Research has revealed that gay individuals residing in other nations often suffer from a form of depression linked to family gatherings during the Christmas season, and that those who are severely afflicted may even contemplate suicide. Over time, many gays either establish boundaries between themselves and their families, or simply avoid large family gatherings entirely.

Couples with children from previous relationships face a similar issue: which set of grandparents do they take the kids to see on the holiday? No matter what they choose, someone's going to be unhappy.

A Mr. Zhu, who lost his spouse many years ago, has been reluctant to marry his girlfriend of more than 10 years, herself a single parent, for precisely this reason. He says that by remaining unmarried, he is free to take his kids to see their maternal grandparents over the holiday. His girlfriend's children are also able to enjoy a fairly stress-free visit with their father.

"If we were to marry, our New Year's planning would have to account for four families," says Zhu. "My girlfriend and her child would probably have to come with me to my parents' home, which would make things much more complicated. Life is short enough already. Why should we make it more difficult than it already is?"

The disputes arising out of the weakening of family relationships can often make people wonder why they should feel obligated to attend a get-together at such a sensitive time. That, in turn, makes it easier to contemplate spending the holiday traveling, -whether in Taiwan or abroad.

In "Getting Far Away for the New Year," author Lolita Hu insightfully observed that when families were more closely bound by blood ties, the Lunar New Year served as a ceremonial means of bringing relatives together from near and far. Nowadays, familial relationships aren't as close and this ceremony of returning has lost its former, almost mythic character. Consequently, the holiday has become one of the year's rare opportunities for a vacation.

For the modern middle class, which used to travel home for the holiday, "Lunar New Year travel now means getting away," says Hu. "The holiday's arrival is a signal to scatter." Hu thinks that in the future staying home for the New Year may well give rise to social pressures, a marker that says that your family hasn't done well for itself in the previous year, that your kids are going to grow up to be provincials ignorant of the larger world, and that you don't know how to lead an interesting life.

Vincent Lin, deputy general manager of Lion Travel, confirms that many people do make a beeline out of Taiwan over the Lunar New Year holiday. He says that over the last 15 years, the industry has come to regard it, rather than the summer and winter vacations, as its peak season.

"In years past, the thinking was that you went abroad after you finished with the Lunar New Year's feast," says Lin. "In recent years, more and more people in northern Taiwan have chosen to leave the country before Lunar New Year's Eve. This may reflect the shift to nuclear families and the growing egocentrism of the modern urban population, which ignores the traditional restrictions on New Year's behavior."

copy.jpg?w=1080&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

Has the Lunar New Year really lost its savor? The holiday, which centers around reuniting with family, offering thanks, and welcoming the new, is still the most important traditional festival in the Chinese-speaking world. But changes in contemporary society and in family relationships have lessened its importance. The photo shows Miaoli's Sanshan Guowang Temple.

Restaurants and hotels have also replaced the home as a place to spend the holiday. Beth Tsai, a public relations manager with the Regent Taipei, notes that people used to spend their Lunar New Year's Eve at home, preparing a meal and chatting quietly with friends. Restaurants were closed and the city's streets deserted.

But that changed roughly a decade ago. The growing number of young housewives who lacked the time, interest, or ability to prepare the difficult New Year's Eve feast represented a new opportunity. Businesses jumped on it, making tasty, convenient, time-saving restaurant meals a great option for families uninterested in going to the trouble of preparing a feast at home.

The trend has also fed the popularity of "take-out New Year's feasts." The market continued to grow after convenience stores entered the fray five years ago and is now estimated to be worth at least NT$300 million. Modern consumers need only spend a few minutes in front of their computers to put together a New Year's feast that includes every dish they could possibly desire.

People who choose to eat at restaurants not only save time, but also, importantly, enjoy a more festive atmosphere than they would at home.

Tsai says that restaurants and hotels often arrange New Year's events to liven up the atmosphere. For example, the Regent organizes traditional goldfish scooping, couplet writing, and dough sculpting activities, as well as putting on dance performances in its main lobby. "Many guests have told us that going out for a meal is a more festive and interesting way to spend the holiday than staying home watching TV and playing mah-jong."

During the Lunar New Year's holidays, unmarried individuals are sure to be urged to hurry up and find a spouse, which is why many prefer traveling abroad to going home.

The best choice for most people today is a convenient New Year's celebration that meets their personal needs. But while ef-fi-ci-ency and individualism have come to dominate the mainstream, there remain many middle-aged and el-derly persons who miss the old agrarian traditions.

Recognizing this, Caijia Village, a veritable Shangri-la for seniors in New Taipei City's Dan-shui District, several years ago began a program centered around the Qifu Baosheng Shrine that aims to revive the meaning of the Lunar New Year.

On the 16th day of the 12th month of the lunar calendar, every household in the village prepares a dish to share with friends and family at the shrine. There, they offer their respects to the gods and console themselves for the previous year's travails. On Lunar New Year's Eve, villagers feast before gathering in front of the shrine. The adults enter to light incense and talk about family matters, while the children snack and set off fireworks. Shrine workers serve everyone piping-hot tang-yuan soup (a sweet soup containing balls made from glutinous rice flour), and even provide elderly residents with red envelopes containing US$1 to ensure that they have something to give the younger generation. The festivities last until midnight and beyond.

The shrine's Cai Ying says that while the traditional New Year's festivities could possibly be simplified, we shouldn't let go of the cultural significance: the holiday's sense of gratitude for what we have, its family reunions, and its welcoming of the new. Cai-jia Village has therefore racked its brains to come up with holiday activities that bring participants together and connect them to our traditions.

Liu Huan-yueh, who writes on folk customs, has a different take on the holiday. He says that the New Year is really about endings and beginnings. If you think of life as a 10,000-meter race, the New Year is like a brief respite every 100 meters. No matter how you ran the previous 100 meters, no matter how your body responded to it, that portion of the race is done. The next 100 meters are the focus of your hopes.

People today don't know which New Year, the Lunar or the Western, is the real New Year. The whole country therefore spends an indolent month between the Western New Year and the Lunar New Year waiting for their Lunar New Year's holidays to get under-way. Liu believes this is unhealthy.

"People have to transition from endings to beginnings," he argues. "They have to let themselves catch a breath so they can persevere in the face of future challenges. Regardless of which New Year they celebrate, they shouldn't ignore its meaning."

Time rolls on and our ideas about how to properly celebrate the New Year evolve in response to the environment we live in, our experiences growing up, and our financial situation. But whether we stick with tradition or try to simplify, the New Year always represents hope. The key is figuring out how to lead the best possible life in the coming year.

Going to a temple to offer incense and pray for good fortune is an essential New Year activity for many Taiwanese. The photo shows visitors to Lu'ermen Mazu Temple in Tainan passing lucky coins over the temple's incense burner.

As the New Year approaches, the Taipei Lunar New Year Festival Market opens for business offering all kinds of holiday goods and snacks for sale.

On Lunar New Year's Eve, the elderly citizens of Caijia Village in New Taipei City's Danshui District recall the Lunar New Year's celebrations of yore by giving the village's youngsters red envelopes containing one US dollar.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)