00:00

To withstand the force of ocean waves and currents, the dikes of stone fish weirs are built with a slope.

With the permission of the International Satoumi Program, a case study on Taiwanese stone fish weirs has been published on the website of the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative by the Agency of Rural Development and Soil and Water Conservation of Taiwan’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Scudding clouds are reflected in the glistening seawater in the pool of a stone fish weir. As we walk along the top of the weir dike, we feel through our shoes the pointed shapes of the rocks from which it is built.

But Xu Hongzhe, a member of the supervisory board at the Taoyuan Stone Tidal Weirs Association, walks nimbly over these same dikes like a hero from a wuxia novel. When he sees a spot with a stone missing, he crouches down and uses a nearby rock to fill the gap.

The nine stone fish weirs in the Kejian area of Taoyuan’s Xinwu District, as well as many of the weirs in Penghu, are regularly inspected and maintained by local residents. Surviving the tests of time and tides, many are still used to catch fish.

Austronesian origins

Many scholars have concluded that the locations of stone fish weirs have a high degree of overlap with the migration routes of the Austronesian-speaking peoples. Lee Ming-ju, a professor in the Department of Tourism and Leisure at National Penghu University of Science and Technology, says: “Although there is no direct evidence to support this hypothesis, based on phenomenology and timelines, I believe that stone fish weirs were used by the Austronesian peoples earlier than by Han Chinese.”

When Lee did field research in the Houlong‡Tongxiao area of Miaoli County, elders told him that long ago in the area there were stone fish weirs built by Pingpu indigenous peoples. Meanwhile, two or three years ago ocean waves uncovered the remains of an old fish weir in Xinwu District, encrusted with oyster shells, which could very well have been constructed by indigenous peoples.

Xu Hongzhe recalls that when he was a child, if adults did not have enough free time, they left checking on the fish weirs to the kids. If the children saw a lot of fish, they would run back and tell the grown-ups to come and catch them.

The Taoyuan Stone Tidal Weirs Association offers experiential activities at fish weirs along Taoyuan’s coast.

Use by migrant workers

It’s interesting that many Filipino migrant workers who use their time off to camp in the windbreak woods at Kejian also know how to catch fish from the weirs. They are even more expert than Taiwanese, using traditional fish spears to catch fish and their bare hands to catch aggressive red-eyed reef crabs.

However, the migrant workers often remove stones to search for crabs hiding in the crevices between them, and the action of the waves moves the remaining stones so that the ones that were removed cannot simply be reinserted into the space. Xu Hongzhe warns that when catching seafood it is best to keep sustainability in mind, and says that local Taiwanese residents only catch large crabs, leaving the small ones to grow up before hauling them in.

A guide explains how to catch fish with a triangular net.

Along the Oyster Shell Trail in Taoyuan’s Xinwu District, visitors can learn about coastal plant life.

How to build a fish weir

The design and construction of tidal fish weirs demonstrates how our forebears knew how to take advantage of marine ecology and tidal regularity. Xu emphasizes that the building of stone weirs requires attention to three key aspects: three contact points, stone shape, and gap filling.

He says that every stone must have at least three contact points with the surrounding stones, as only then will the structure remain stable. When placing later stones, craftsmen must assess their shape to select appropriate rocks. Meanwhile, there are invariably interstices between stones, so it is necessary to find a rock that is slightly bigger than the opening and knock it into place to “fill the gap.” Stones that are too small will be washed out of place by the waves.

For the top layer, stones are placed upright rather than being inclined. The angles are different for every layer, and like the game Jenga, if one rock is removed it could cause the whole structure to collapse.

Lee Ming-ju states that generally speaking for stones to be stable they must be placed horizontally. However, tidal weirs have to withstand the force of sea waves striking them from all directions, so the stacked stones need to form a slope. Though our ancestors had no conception of fluid mechanics, they understood the need to temper the force of the waves.

Hu Chia-chun, secretary of the Taoyuan Stone Tidal Weirs Association, notes that this year the association will guide and assist the repair of fish weirs in Taoyuan’s Xinfeng District and New Taipei’s Sanzhi District. They also offer free classes in weir-building techniques, and newcomers or volunteers who are passionate about environmental education are welcome to attend.

Tides and ocean currents bring aquatic life into fish weirs in intertidal zones.

Isle.Travel works with fish weir craftsmen to offer courses on weir repair and how to coexist with the sea. (courtesy of Isle.Travel)

The diverse shapes of fish weirs

Because of the variations in ocean currents and topography in different locations, there are differences between the fish weirs around the Penghu archipelago and those around the island of Taiwan. Lee Ming-ju notes that the usually arc-shaped tidal weirs on the coast of Taiwan proper rarely have enclosed pools within them, because the intertidal zones are mostly narrow. In some places a second weir is constructed behind the first, creating a fish-scale pattern.

Lee adds that because the intertidal zones in Penghu are generally broad, in order to concentrate the catch the builders constructed a smaller pool (known as a pound or atrium) inside or outside of the curved weirs. The pound is generally heart-shaped, with two long “arms” attached that can be straight or curved. In response to local tidal conditions and topography, stone fish weirs are built in various shapes, with one, two or even three pounds.

There are also “substructures” within the pounds. For example, there might be a narrow passageway to catch rabbitfish or neritic squid, or a “tooth” (a short projecting levee for fishers to stand on) to catch silver-stripe round herring.

In Penghu there is a “stone fish weir song” about inspecting and building fish weirs, with lyrics in Taiwanese. It records the unique soundscape of stone tidal weirs.

Taiwan’s Executive Yuan has designated Penghu’s cluster of stone fish weirs as a potential World Heritage Site. The Bureau of Cultural Heritage of the Ministry of Culture has prepared Chinese and English language introductory texts for their inclusion on the World Heritage List.

Moreover, in combination with multiple aspects including youth participation, fishing village regeneration, ecotourism, and intertidal zone conservation, stone fish weirs represent the spirit of sustainability and peaceful co-existence with nature. In response to an application from the Agency of Rural Development and Soil and Water Conservation of the Ministry of Agriculture, the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI) has published a case study of Penghu’s fish weirs on its website.

Stone fish weirs can serve as centerpieces of ecotourism itineraries, promoting eco-friendly fishing methods and enhancing public awareness of marine environmental conservation.

Visitors experience the feeling of catching fish with a Taiwanese beach seine.

Making a list

Lee Ming-ju says that stone fish weirs are actually not as accessible as one might imagine. They are often covered by the tide, and can only be reached for two to three hours of daylight each day.

In 2018, Lee’s students Yang Fu-tzu and Jerry Tseng founded the social enterprise Isle.Travel Studio based on their love of stone fish weirs. Working with weir owners in Penghu, from March through November they offer a variety of itineraries including “Stone Weir Nightwalker,” “Stone Weir Explorer,” and “Stone Weir Restorer.” Activities include nighttime sand shrimp fishing with lights and searching for horseshoe crabs. The enterprise donates 5% of profits to restoration work and also provides opportunities for customers to take part in such work. It’s a sustainable business model.

Isle.Travel has also recreated a traditional fish processing workshop for a local community. Completed in 2022 after three years of effort, it offers clients a chance to try their hands at Penghu’s longstanding food preservation culture. Since this is one of the foundations of fish weir culture, it forms a starting point for exploring weirs.

Jerry Tseng not only leads tours but also manages the “Stoneweir.info” platform, where he documents weir building techniques, structures, and local sayings. He has compiled a public registry of 654 stone fish weirs with names, GPS locations, history, and structural details.

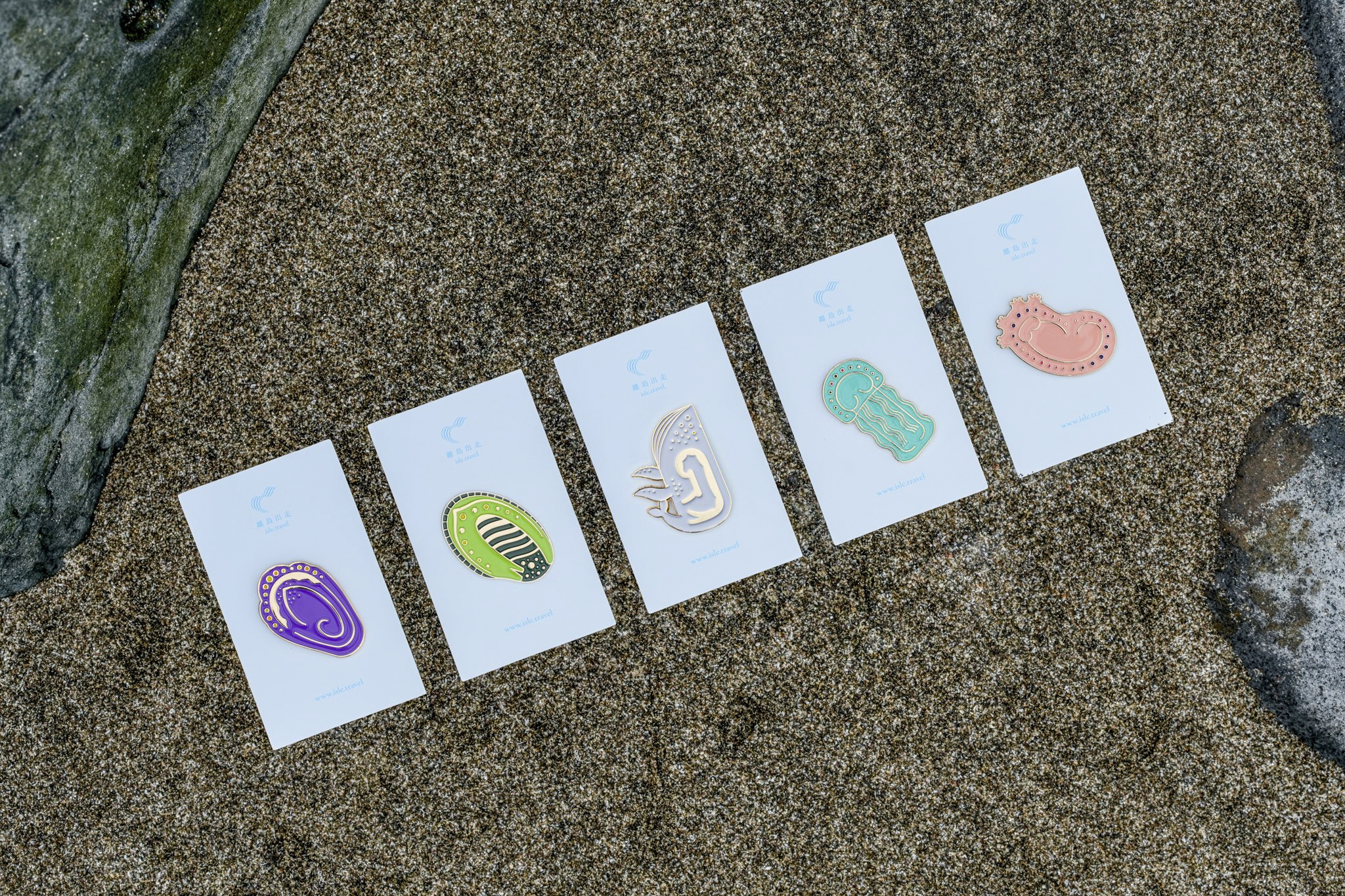

Cultural and creative products related to stone fish weirs. (courtesy of Isle.Travel)

The vitality of fish weirs

The Taoyuan Stone Tidal Weirs Association also offers an ecotour in Kejian. Visitors can go directly into the weirs to experience the fun of fishing with nets. In summer, there are schools of anchovies and silver herrings off Xinwu Township. In winter, when waves are bigger, schools of fish don’t approach the shore, but there are still nibblers, sea bass, Japanese seaperch, fourfinger threadfin, and even large East Asian fourfinger threadfin to be caught.

Yang Fu-tzu notes that the practice of catching fish with stone weirs has flourished over many generations. Visiting fish weirs today, one can not only enjoy marine ecosystems, but also reflect on how humans can peacefully coexist with the sea. Many foreign visitors in particular are impressed at how such a small archipelago as Penghu can offer such world-class scenery.

Lee Ming-ju says that it is unfailingly astonishing to experience these weirs. Once on a visit to Tudigong Islet in Penghu he swam into the pound of a fish weir, where the water was over his head. Inside the pound, which was bigger than a classroom, a huge school of silver herring were swimming about, glittering in the sunlight that penetrated the water, and he could simply reach out and touch them.

“I’ll never forget that sensation as long as I live, and when I look back over my life, I feel that such an experience makes it all worthwhile.” This is the vitality brought to fish weirs by the combination of tides and ocean currents.

Taiwan’s Executive Yuan regards Penghu’s stone fish weirs as a potential World Heritage Site. (courtesy of Lee Ming-ju)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)