Fataan: The Village Beneath Mt. Mahsi

Laura Li / photos Hsueh Chi-kuang / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

September 2002

In recent years, as well as working to develop the economy, many caring people in Taiwan have come to attach importance to community regeneration, and in the process of exercising "good-neighborly concern," have brought a more individual and cultured aspect to previously drab communities. If we look more closely at the success stories among efforts toward community regeneration, we see that they all involve felicitous combinations of the three factors of "individual contributions," "unique characteristics," and "effective strategies," through which some communities have been able to create an attractive sense of warmth.

To give readers inside and outside Taiwan an insight into the current situation and the strategies being adopted in community regeneration in the ROC, Sinorama is collaborating with the Council for Cultural Affairs to produce a series of reports introducing distinctive communities in Taiwan, which we hope readers will find informative and enjoyable.

The village of Fataan belongs to one branch of the "Hsiuku Amis," and under ROC government administration is part of Kuangfu Rural Township in Hualien County. Kuangfu Rural Township has a population of 16,000, of which Fataan accounts for about one-third. Its population of over 5000 is equally divided between Amis and Han Chinese. Affluent Fataan was selected by the Council for Cultural Affairs for the first round of "holistic community building" eight years ago. The results have been outstanding.

On a gorgeous August day, our car drives out from Hualien City on Provincial Route 7, southward along the coast, through Fenglin and across the Fataan Bridge to the largest Amis tribal village in all of Taiwan: Fataan.

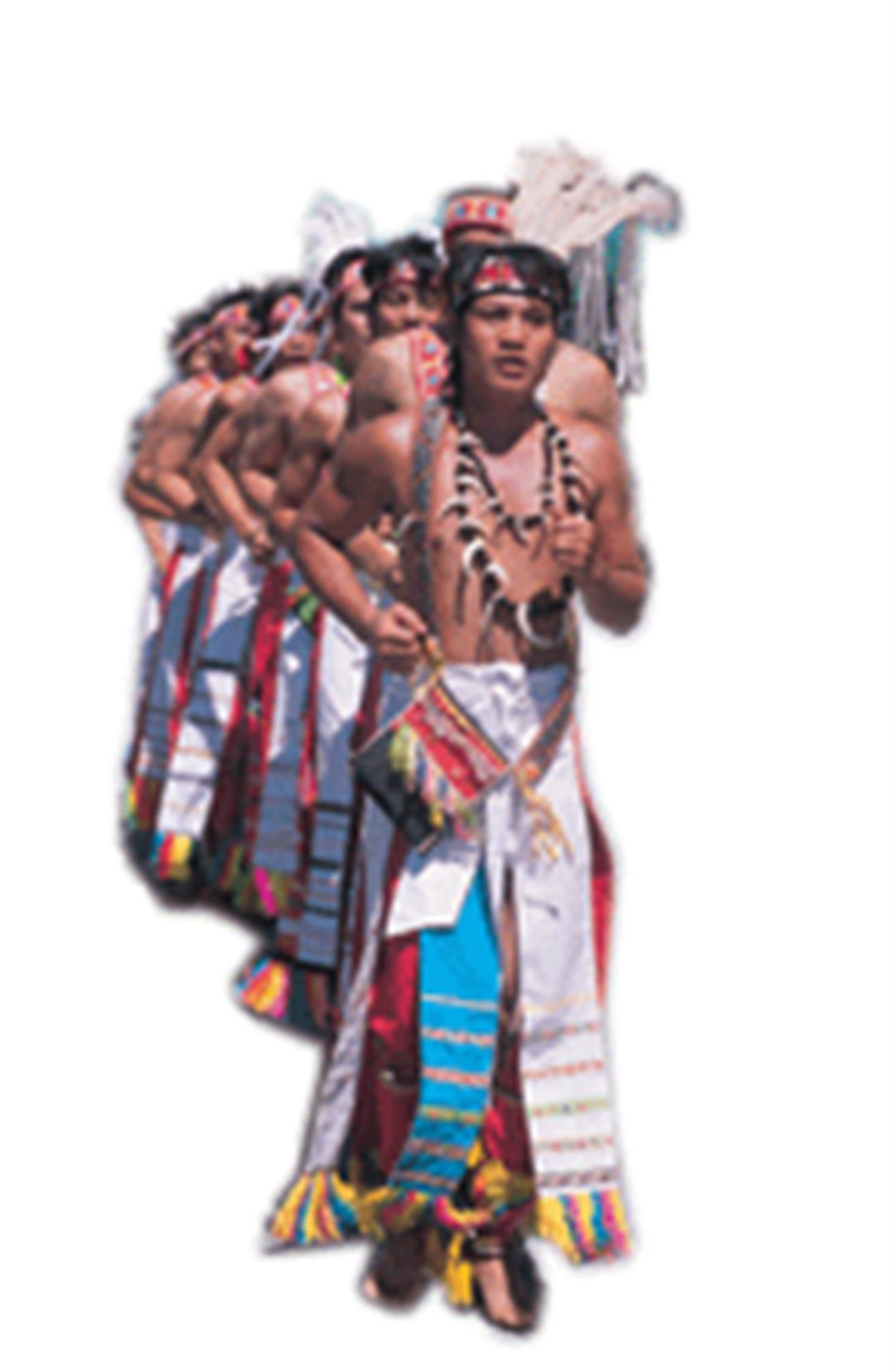

(facing page) Fataan is the main village of the Hsiuku Amis. The are numerous local sub-branches. This group of Amis youths from another village, with feathers in their hair and necklaces of wild boars' teeth dangling from their necks, are reporting to the chief at Fataan about their own Harvest Festival celebration.

Sustainable tourism

To the right of the tribal village is the holy mountain Mahsi, which rises to nearly 2000 meters and is shrouded in cloud and fog all year long. Traditional Amis balakau fish ponds form a line in the swampy land at the foot of the mountain. The flat land on the other side of them is dotted with lotus pools, with a few flowers still in bloom. The peaceful landscape looks like it could have been the subject for a painter-poet of ancient times. Last year in July Typhoon Toraji provided horrifying scenes of mudslides and flooding here. By now, they have nearly been forgotten.

"The Aboriginal tribesmen have an amazing vitality and resilience; they have the ancient wisdom of how to coexist with nature," says Tsai Yi-chang (Lalan-Wunake), amid the displays of wooden carvings and ancient implements at the Fataan Cultural Hall. Tsai, who has much expertise in the area of Aboriginal culture, works on the government's "holistic community building" program here.

Weekends and summer vacations are when Tsai is busiest. The program has been going for several years, and Fataan has become famous for its Aboriginal lifestyle. The "lifestyle district" to the right side of Route 9 is one of its main tourist attractions.

Calling for "sustainable tourism," Tsai Yi-chang explains that he hopes that each time tourists visit they can come away with different experiences of joy and surprise. The first time they arrive they can observe how the Amis gather wild plants, and how the children make mud turtles under the trees as their grandmothers shell lotus seeds. At night, after having their fill of freshly caught fish and enjoying some short harvest festival ceremonies, they can follow fireflies along a path and observe some Moltreche's green tree frogs. Or else they can gaze skyward at the many twinkling stars. Tsai guarantees that visitors won't want to go to bed until late at night.

The second time tourists come they might want to learn wilderness survival skills for an hour; and then study the tribe's religious beliefs and complex social structures.

"I believe that tourists won't want to passively come to 'look at' Aborigines. Why would Aborigines want to let you look at them, anyway? Tourists coming here will want to lean and interact with the Aborigines," says Tsai Yi-chang, who is incomparably proud of his own culture.

Having been raised in a matriarchal society, Amis men have good-natured and humorous dispositions. Tsai Yi-chang (Lalan-Wunake), who is known for his erudition about Aboriginal affairs, speaks in a manner that is always humorous and right to the point.

Three-story fish houses

Indeed, with community holistic building promoting "cultural enterprises and entrepreneurial culture," Fataan is marching in the direction of tourism that puts an emphasis on understanding the native culture and way of life. Gold nuggets found amid the tribe's traditions are also having a big impact on the community's long-term development.

Take the traditional balakau fish ponds, which are unique to the Amis. "Five years ago when Tsai Yi-chang said that he wanted to revive this method of catching fish, all of the village elders berated him, asking him why he would want to build balakau in this day and age," laughs Cheng Shun-cheng, a village resident who has worked with Tsai for several years on holistic community building. Cheng had never expected that this method of raising fish, which reflected wisdom gleaned from adapting to the primitive, swamp-like conditions hereabouts, would today become one of Fataan's biggest selling points.

Not more than five square meters in area, with water no deeper than a man's waist, balakau are "three-story houses" built for fish. In the barrel-like lowest level, which is constructed out of bamboo, live "shy fish without clothes" (or rather scales), such as walking catfish and swamp eels. The middle level, built out of sticks of Chinese crape myrtle, is for shrimp. Smart and nimble scaly fish inhabit the top level, which is built out of bamboo that overlaps with the second level and is topped with water grasses.

When the excrement from the top layer of fish seeps down to the middle layer, it acts as an "organic farm" producing algae that keep the shrimp well fed. And when the shrimp grow well, this helps to produce ample yields of all varieties of fish in the Hualien River.

Apart from the ecologically marvelous design, "the balakau also have meaning as part of the living cultural inheritance of Fataan. The Amis were the only Aboriginal tribe in Taiwan to develop a system of 'private fishing areas.' A balakau can be passed down from generation to generation and last for a century.

Typically, after a funeral or a celebration, respected elders will hold a "fish pool maintenance" ceremony to help people settle down emotionally. While they perform the maintenance, the whole clan will gather together and form different age-based squads to do the work. At the same time, they cultivate discipline and leadership skills in every age group.

(facing page) Fataan is the main village of the Hsiuku Amis. The are numerous local sub-branches. This group of Amis youths from another village, with feathers in their hair and necklaces of wild boars' teeth dangling from their necks, are reporting to the chief at Fataan about their own Harvest Festival celebration.

One for all, and all for one

"It could be said that 'holistic community development' reveals the basic nature of our traditional Amis culture," says Tsai Yi-chang. Whether for harvesting crops, hunting, building bridges and roads, or going into battle, tribal life required solidarity.

"In the past no one was afraid of earthquakes and fires, and they weren't worried about having to replace their thatch roofs every three years either," Tsai points out. Three days after a fire, the new building would be up again with the help of your neighbors. A little incident would become an "excuse" for everyone to get together and have a good time.

"The Amis have always been a society in which people help each other out and share," says Tseng Kuo-fan, the former village head of Tatung Village in Kuangfu Rural Township, who worked with Tsai promoting holistic community building. Unfortunately, with all the best intentions, past governments built cement dykes along the rivers, and filled in the swamps. As a result, the fish pools dried up. The thatched houses, out of sanitary considerations, were replaced with reinforced concrete residences.

With this wave of "modernization," the traditional festivals of the "balakau culture" were replaced with "pig-slaughtering culture." Because the slaughter of pigs was so brutal, underage children were not permitted to come near, which made it just that much harder to pass along the culture. At the same time, sturdy concrete buildings will stand for a century, and so neighbors have fallen out of the habit of helping each other and have thus lost an opportunity to gain a sense of interconnectedness.

In 1995, in response to the government's call to move industry to the East Coast, Tsai prepared to take his lead pipe processing company back to his hometown. In his boredom as he was waiting, Tsai took up a camera and started to take pictures all around the tribal village. Much to his surprise, it awoke his long dormant love of the old ways.

"In comparison to other tribal villages, Fataan is affluent and has a high level of culture," says Tsai. "It even has a 'strivers' row' lined with impressive houses."

It's just that behind these large homes were stories of untold suffering. Particularly in the 1970s, people of his clan left to build the North Link Rail Line, or to work on fishing boats far out at sea, or even to build highways in the desert sands of Saudi Arabia. After being away from home for so many years, you would trade up for a fancy house, but you would discover that your children had picked up bad habits and your wife had fallen out of love with you. People became more calculating and lost some of the tribal people's innocence and happy-go-lucky qualities.

"With the promotion of 'holistic community building,' I began to think about how tribal people could use their local and traditional culture and develop their native talents so that they wouldn't need to leave home to make a living."

Tsai points out that when you stay in the tribal village you can see your children grow up. At the same time, it's the only way to give the village a new lease on life. When the Council for Cultural Affairs began to promote "holistic community development" all around Taiwan, Tsai grabbed hold of the opportunity and threw himself into this difficult social undertaking.

The method of raising fish in balakau, three-storied tanks, bears witness to the wisdom of Fataan's ancestors. Taking good care of these balakau shows the discipline of a family and maintains its honor.

Don't break a leg!

The first approach that Tsai thought of taking was developing wood carving. Wood carving had been a traditional Aboriginal art form, but had gradually declined over the past century with the Christian taboo against "graven images." Tsai specially invited Lin Ah-lung, a famous Tabalong carver who was a director at the Tabalong Elementary School, to come and teach classes. As intended, these classes pricked the local tribesmen's interest.

This is the fourth year these classes have been offered, and by now more than 100 locals have enrolled. Six or seven have already graduated and established their own workshops. And there have also been classes offered in ceramic beads, dance, and growing lotuses.

Yang Ching-te (Lawasi), a member of the first carving class who has now become quite famous as a carver himself, recalls that he used to do odd jobs as a metal worker in Hualien. When he heard that there were going to be carving classes offered back home, the idea of trying something new and fresh attracted him. When he first started, the right and left legs of the people he carved were indistinguishable, and he would get the five fingers reversed. He never expected to get so addicted to carving.

"When you take a chisel to a piece of wood, you've got to have an image in mind." He doesn't drink any more, he says, "because a drunken hand will shake. If I got drunk and broke my own arm or leg, that wouldn't be a big deal. But if I broke the leg or arm of one of my carvings, that would be true heartache!"

During those recent years when the economy was booming, Yang Ching-te was making from NT$60,000 a month to more than NT$100,000, relying on groups from big hotels or independent tourists who visited his workshop. He came to understand that "you really could make money from unique culture!"

With the current hard times, Yang Ching-te's income has sharply declined. But he's not discouraged. "I'm working hard to finish a hundred excellent works, and then I'm going to hold an exhibit," he says. "Just like Han Chinese artists, I'll invite the media to make reports and increase my name recognition!" With this he grins, exposing his teeth, which are stained red from chewing betel nuts.

(facing page) Yang Ching-te, who stepped into the world of wood carving out of curiosity, has now entirely immersed himself in it. It's completely changed his life.

Persevering for the tribe

This year Huang Ko-jung and Chang Chiu-ying, a husband and wife in their fifties, enrolled in the dance and lotus growing classes. The backgrounds of students in these classes are quite varied- from ship captains to form setters for building concrete structures. In the summer they put on a "Lotus Festival," and they regularly practice traditional dances. They understand and identify with the concepts behind holistic community building and developing local enterprise.

Recently, as the tourist season has peaked with the Harvest Festival being celebrated in villages all over eastern Taiwan, they have all been carrying cell phones so that the head of the dancing group can contact them at a moment's notice.

"Most of our sons and daughters have gone to the city to work, and it's a big deal when they find the time to come back," says Chang Hsiu-ying. "Hence, we old folk have to do the work of promoting and carrying on our cultural legacy." Their performances not only entertain honored guests, but they also make their grandchildren in the audience proud of them for being so important. Making children proud of their own culture is the best kind of education.

Yet it cannot be denied that the recent hard times have impacted the economic opportunities for these cultural enterprises. Tourists are adopting the strategy of traveling without buying souvenirs, and this has put the cultural workers here under tremendous pressure. With cultural tourism and "leisure farming" losing some of their luster, the villagers are most concerned about this question: "How are we going to make ends meet?"

These are hard times economically, but Fataan at least has a certain cachet as "the most authentically traditional of Amis villages," allowing holistic community building to continue working to some degree.

"Our mission is to restore community values," says a determined Tsai Yi-chang. "No matter what, we're going to keep at it!"

(facing page) Fataan is the main village of the Hsiuku Amis. The are numerous local sub-branches. This group of Amis youths from another village, with feathers in their hair and necklaces of wild boars' teeth dangling from their necks, are reporting to the chief at Fataan about their own Harvest Festival celebration.

Sending off their eldest grandson to military school, the clan gathers at dusk, eating grilled fish, singing traditional songs, and enjoying themselves.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)