That's Fresh! --Seafood in Chinese Culture

Chang Chin-ju / photos courtesy of the National Palace Museum / tr. by Robert Taylor

February 1999

From the raw fish eaten in Guangdong, to the wine-soused live prawns and crabs eaten in Zhejiang; from Su Dongpo, who gambled his life eating pufferfish and raw oysters, to emperors who had Reeve's shad transported hundreds of miles in ice boats and by express courier to their tables: over thousands of years the Chinese have sampled every kind of creature from their country's waters, and have tried all kinds of ways-from cold storage to cooking, drying or pickling-to keep their seafood tasting fresh. In doing so they have written a page in Chinese cultural history no less remarkable than the current craze for live seafood in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The world's most avid seafood eaters today must be the Japanese, and Japanese restaurants offer a great variety of refined and exquisite seafood dishes. Seafood cuisine in Taiwan has been influenced by the Japanese in the past. But if we delve further back into history, we find that the dishes the Taiwanese learned from Japan may well have been invented by their own Chinese ancestors.

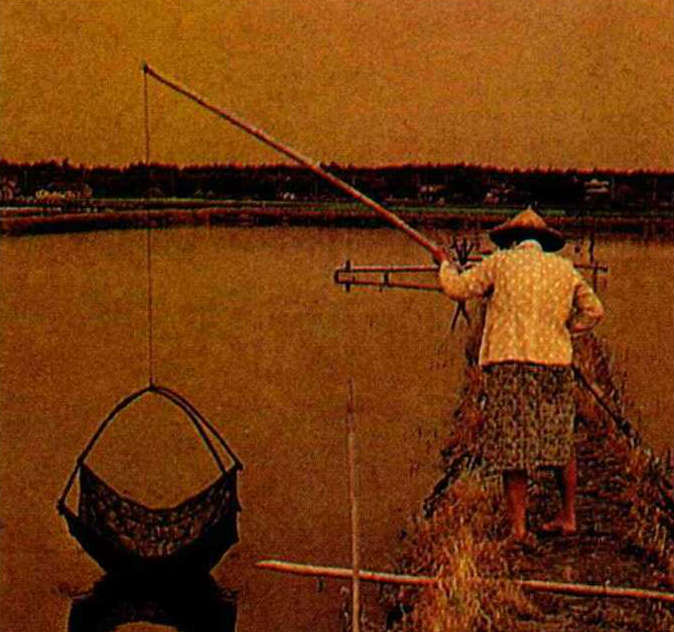

One is a woman by a shrimp pool in Ilan County; the other, an old fisherman in the 15th-century painting Fishing, by Ni Duan. Yet both are using the same equipment. Just as net designs have been passed down, so have Chinese traditions of eating aquatic produce, from the inland freshwater fish and crustaceans of the earliest times to the wide variety of marine and freshwater species eaten by Chinese today.

Sashimi's pedigree

Dr. Hung Chien-te of Taipei's Yangming Hospital encourages people to eat fish, and has also studied the history of fish eating. He says the "fish sushi" served in Japanese restaurants today has its earliest origins in the raw, marinated minced fish and pork mentioned in the Book of Songs from the late Zhou dynasty (c. 11th century BC-256 BC).

In ancient China, salted fish was also wrapped in rice and allowed to ferment. Foods fermented in this way, with their characteristic vinegary taste, reached the height of popularity in the Tang (618-907). At that time members of the Japanese nobility took chefs skilled in making this dish back to their own kitchens in Japan, and there it developed into a form in which fish is placed into vinegar-soaked rice, Hung Chien-te explains in his "Sashimi Legends" series of articles.

Back in the Zhou dynasty, Confucius (551-479 BC) said: "Food can never be too refined; kuai can never be sliced too thin." "Kuai" was thinly sliced fresh raw fish, beef or mutton. In ancient China it was eaten with different condiments according to the season, such as scallions in spring or leaf mustard in autumn.

One is a woman by a shrimp pool in Ilan County; the other, an old fisherman in the 15th-century painting Fishing, by Ni Duan. Yet both are using the same equipment. Just as net designs have been passed down, so have Chinese traditions of eating aquatic produce, from the inland freshwater fish and crustaceans of the earliest times to the wide variety of marine and freshwater species eaten by Chinese today.

No taste like home

Old Confucius was not the only one who was partial to raw fish. Poet Zhang Han of the Western Jin (265-317) was appointed an official in the capital Luoyang. But when the autumn winds began to blow he was so overcome with nostalgia for the thick watershield soup and sliced raw sea bass of his native Suzhou that he said: "What matters most in life is to be content. How can one be tethered so far from home just for the sake of rank?" Zhang Han's willingness to give up his official post for the dishes of his native place has earned him a lasting place in the affections of Chinese epicures.

This act brought raw sea bass to fame, but when the immortal poet Li Bai (701-762), whose greatest passion in life was to roam the land visiting famous mountains, came to Sheng County in Zhejiang Province, he was quick to avert any unwarranted suspicions: he had not gone there for the sea bass, but purely to admire the landscape. Another Tang poet even carried a knife with him at all times so as not to let slip any opportunity to eat sashimi. A third, Du Fu (712-770), wrote: "Lovers tread upon the rocks, fresh fish comes from the river"-though mainly preoccupied with the wellbeing of the nation and the people, he was evidently also a sashimi fan.

The biggest problem with eating raw seafood is the possible danger to health. History of the Latter Han records how a prefect of Yangzhou felt an oppressive irritation in his chest, was red in the face and could not swallow food. After taking some medicine given him by the great physician Hua Tuo, he spat up half a gallon of worms, mixed with fragments of raw fish.

Perhaps because the difficulty of keeping food fresh in ancient times made eating raw fish a health hazard, by the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) the Chinese rarely ate fish raw. But the habit of eating raw fish did not die out completely, and the Qing-dynasty travelogue Notes on Annam describes how the Cantonese ate pufferfish: "They slice it thinly; the red flesh is streaked with white. Slices so light they lift when blown; as thin as a cicada's wing, they melt in the mouth." Slices of fish so thin that they take to the air-this description seems to betray a skill with the knife which many modern-day chefs would be hard put to equal.

It is said that today it is only in congee and noodle restaurants in Guangzhou and Hong Kong that one can still buy live grass carp to be cut into thin slices and served mixed with shredded scallions and ginger, and spotted with pungent oil. "This is a last surviving vestige of the kuai of old," writes Professor Lu Yao-tung of National Taiwan University's history department in his book Going Out to Visit the Past. He also quotes an ancient folk song which describes how in Guangdong, "At the winter solstice the aroma of raw fish is everywhere." But, he adds, "Anyone who has lived in Hong Kong knows that nowadays raw fish is not eaten only at the winter solstice."

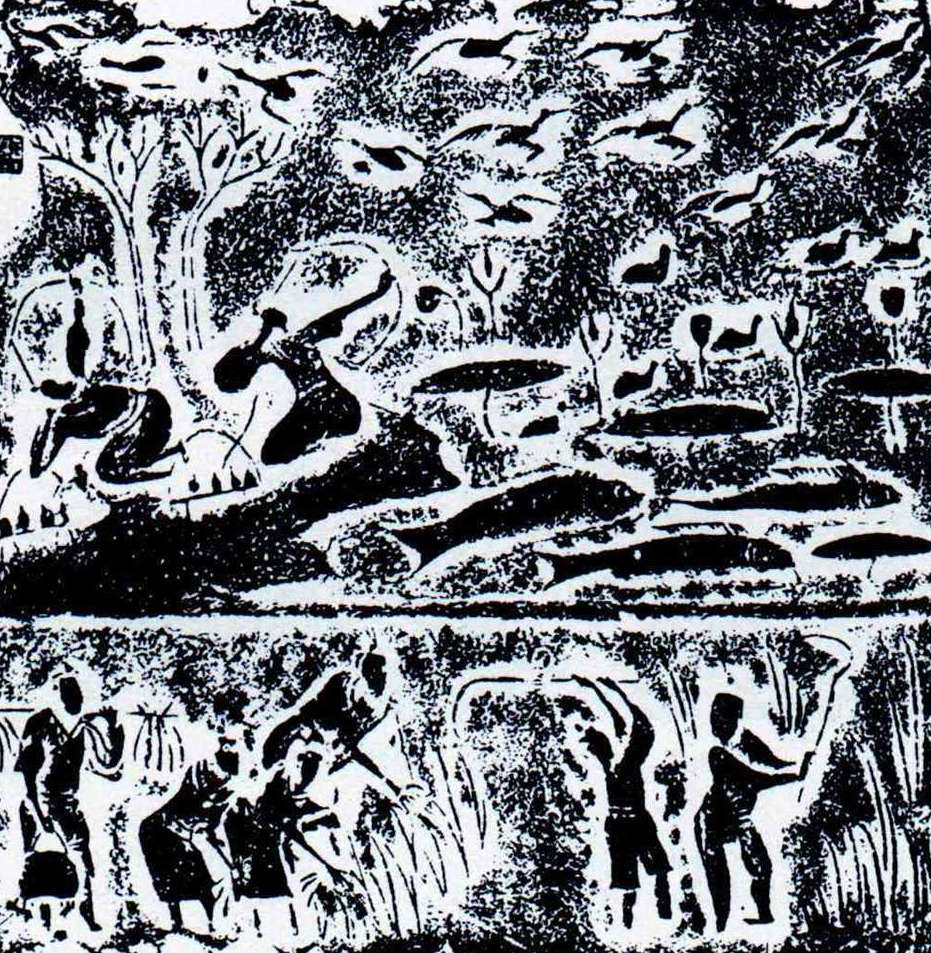

The autumn leaves fall, the pond is full of water, fish sport among the ducks bob contentedly-- these images from a carved Han tile discovered in Sichuan show that the ancient Chinese lived not only by farming, but also by fishing and hunting.

A raw deal

Eating foods cooked speeds up the digestive process, enabling humans to extract nutrients more quickly, thus raising their IQ and boosting the development of civilization. But traces of the age when our ancestors ate all their food raw have not completely disappeared; instead, raw foods have been developed into delicacies. Today, many nations still retain the ancients' habit of eating raw foods, particularly seafood. In France they eat raw oysters, and in Holland raw herring, with no less gusto than the Chinese.

If we "analyze" the fresh flavor of seafoods using modern scientific methods, we find that in fact seafoods-along with pork, mutton and beef-are rich in proteins, which contain amino acids and small quantities of nucleic acids, both of which produce the fresh flavor so pleasing to human tastebuds. But seafoods have a high water content, their flesh is delicate, and they are stored in a wet environment; all these factors encourage microorganisms to multiply rapidly. Because seafood goes bad so easily, it is particularly important to eat it fresh.

(facing page) The fresh seafood served in Hong Kong's floating restaurants attracts diners of every nationality.

Three rivers, four seas and five lakes

Gourmets today divide Chinese cuisine into three regions coinciding with three great rivers: the Yellow River, the Yangtze and the Pearl River. Although the political center of China in ancient times was in cities far from the sea such as Chang'an (modern Xi'an) and Luoyang, those who lived close to rivers ate food from the rivers, and those who lived close to lakes ate food from the lakes. The Yellow River basin-the cradle of Chinese culture-provided a rich harvest of freshwater fish and crustaceans, and thus gave birth to Chinese people's taste for eating all kinds of aquatic produce fresh from the "three rivers, four seas and five lakes."

Even the paleolithic inhabitants of the Upper Cave at Zhoukoudian near Beijing left behind fossilized remains of common carp and grass carp, and the gourmets of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256 BC) must have done a good job of promoting the local Yellow River delicacies of carp and blunt snout bream, as these critical lines from the Book of Songs suggest: "If you eat fish, must it be bream from the Yellow River?"; "If you eat fish, must it be carp from the Yellow River?"-evidently everyone was eating bream and carp. To congratulate Confucius on the birth of his son, Duke Zhao of Lu presented him with a gift of carp, so Confucius named his child "Carp." But when Mencius (c. 372-289 BC) had to choose between eating fish or eating bear's paw, he preferred bear's paw. Could it be that he too frowned on the fashion for fish?

Although each region differs in what foods are available, it would be wrong to suppose that people living far from the sea in ancient China never tasted genuine seafood from the ocean. "History of the Xia" in Records of the Historian tells how when Yu was taming the flood waters around the 21st century BC, he also made tours of inspection throughout the land, and identified the best local produce of each area. After he established the Xia dynasty, the tributes he commanded to be brought from all over his empire included not only fish from the Huai River basin, but also "sea produce" from the Shandong peninsula.

In fact, many aquatic creatures are adapted to both marine and river habitats. The Classic of Mountains and Seas, from the Warring States period (475-221 BC), records that pufferfish are poisonous, and Wang Chong (27-c. 97) of the Han dynasty further notes that the poison is in the fishes' ovaries and liver. Su Dongpo (1037-1101) of the Northern Song once said, "If you have the chance to eat pufferfish, isn't it worth the danger?" He is said to have been more than willing to risk his life to eat the pufferfish that live along China's coasts. Every spring when their breeding season comes around, the pufferfish swim up the Yangtze, Liao and Bai Rivers. This is why when Su Dongpo wrote: "When the river flows warm in spring, the ducks are the first to know," he followed it with the line: "This is when the pufferfish yearn to swim upriver."

The best known fishing grounds for Reeve's shad, which from the Ming dynasty onward was always an item of tribute, were the Qiantang River in Zhejiang, the Xi River in Guangdong, and the Yangtze. But this particular migratory fish does not swim upriver to spawn until the fourth or fifth lunar month. Astute humans gathered to catch the fish as they moved upstream, so although Reeve's shad were caught in rivers, to refer to them as seafood is in no way mistaken.

On the River at Tomb-Sweeping Festival, by Zhang Zeduan of the Northern Song, shows how in the flourishing city of Kaifeng, thousands of baskets of fresh fish were carried into the city every day, and restaurants served all kinds of seafood dishes.

The product of a fish-eating culture?

However, although the daring fishermen of the coastal state of Qi in the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC) were already sailing far out to sea to fish all night, they did not compare with today's deep-sea fishing fleets which can roam the oceans throughout the year. Thus quick-witted people developed aquaculture, to bring fresh, live fish within customers' easy reach. Jia Sixie of the Northern Wei (386-534), who was all in favor of fish farming, said that without it, "Unless you are close to a river or lake, you can't get a three-foot carp for love or money."

After military strategist Fan Li of the late Spring and Autumn period had helped King Goujian of Yue rebuild the fortunes of his realm, he retired to the seclusion of the mountains and forests of Tao, in what is now Shandong Province. But in fact this was the start of a second career, for the earthenware tubs in which he raised carp covered an area of several hundred hectares, no less than that of many fish farms in Taiwan's Pingtung County today. Fan also wrote China's first fish farming manual, thus paving the way for the aquaculture industry of later generations. From the Tang dynasty onwards, it became common practice to raise such fish as common carp, mud carp, blunt snout bream, black carp and grass carp together, with the different species-some carnivorous and some herbivorous-occupying different niches within the waters of the same pond. "From a modern perspective this was very scientific, and consistent with maintaining an ecological balance," says aquaculture nutritionist Chuang Chien-lung.

With a growing variety and quantity of fresh fish coming from the seas, rivers, lakes and fish farms, our ancestors developed an increasingly comprehensive set of "tools" for eating them. Though many suppose the Chinese adopted chopsticks for ease of picking food out of soup, some have noted that it is easier to pick up delicate fish meat with chopsticks than with a knife and fork. Entrepreneur and gastronome Chiu Yung-han favors the idea that "chopsticks are the product of a fish-eating culture."

As early as the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties, there was the practice of cutting blocks of ice from frozen rivers in winter to use for the cold storage of the fresh and dried fish sent in tribute from throughout the empire. Every winter an official called the "iceman" would send people out to cut blocks of ice to be stored in the imperial icehouse, which had close to a hundred workers. Feudal kings such as Helu of Wu and Goujian of Yue also had their own icehouses.

In The Dream of the Red Chamber, a crab banquet at the Jia residence costs as much as ordinary folk would spend on food in a year. Details from the Qing-dynasty painting Sea Produce (facing page) illustrate how, as their taste for crab developed, the Chinese came to make ever finer distinctions between different kinds of crabs.

All the fruits of earth and sea

The Han-dynasty dictionary Shuo Wen Jie Zi, completed in 100 AD, lists over 70 fish species; the people of the time were growing more and more sophisticated in their categorization of fish and their ways of preparing them. But people in olden times made the best use they could of all the resources of both land and sea, so naturally they did not only eat fish. By the beginning of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC), mussels, clams and whelks had all reached the imperial dining table.

In the Sui dynasty (581-618) the Grand Canal was opened, and this accelerated cultural and economic exchange between north and south. Hubei and Hunan, and the river and lake country south of the lower Yangtze and in Guangdong and Guangxi, supplied all kinds of aquatic produce to other regions.

Aquaculture flourished, and even during the Sui people began seeding Lake Tai with artificially bred predatory carp eggs; in the Tang, specialist fish fry hatcheries emerged. In the Song (960-1279) the laver of Pingtan in Fujian was added to the list of tribute items. A poem by Mei Yaochen (1002-1060) describes how the fisher folk of his time made bamboo enclosures along the sea shore to raise oysters, and how the little oysters thrived amid the briny waves. By the early Qing, the area of the Guangdong coast covered by oyster farms sometimes reached one to two thousand hectares.

The late epicure Tang Lu-sun once described how the people of Ningbo in Zhejiang traditionally ate raw oysters by the plateful, scooping the plump, sweet flesh straight from the shells. In fact, dietary habits are influenced by available resources, so for people who live by the sea to eat large quantities of seafood is not merely a matter of preference. The raw oysters served in the French style in the restaurants of Taipei's luxury hotels today are flown in, and are so expensive that they are counted out one by one, making it impossible to eat one's fill in the way coastal dwellers are accustomed to.

Written records of the Chinese eating crab go back 3,000 years, but what they first ate were not sea crabs, but lake crabs from the Yangtze River basin. The great lakes which absorb the Yangtze's excess flow also gave the crab its place in Chinese cuisine. The Tang dynasty saw the first monograph on crabs; its author Lu Chun praised their flavor as unmatched by any other food.

Freshwater crabs include both river crabs and lake crabs. Li Dou of the Qing dynasty wrote that the crabs of the River Huai, though large, had little flavor, so lake crabs should be the connoisseur's choice. During the turbulent years at the end of the Yuan dynasty, Ni Zan (1306-1374), one of the greatest painters of his day, plied the waters of Lake Tai in a small skiff, wearing a grass raincoat and bamboo hat. His Food and Drink of Yunlin Hall records only a modest number of dishes, but because his home was by the lakeside they are all "seafood" recipes of the kind most popular in Taiwan today; they feature fish, prawns, crabs, river snails, clams and pen shells. Ni boiled crabs with ginger, purple perilla, Chinese cinnamon and salt; when the water boiled, the whole thing was stirred, and when it boiled again the crabs were ready to eat. He stressed that they should be eaten as soon as they were boiled, and only a one-person portion-two crabs-should be cooked at a time; one should not put them on until one was ready to eat. Ni's recipes seem little different from today's, though less varied and simpler-crab boiled in a light broth is now little seen.

Incurably crabby

In his epic novel The Dream of the Red Chamber, Qing author Cao Xueqin (d. 1763) puts these words into the mouth of Lin Daiyu: "Pincers swelled with jade-white tender flesh, a shell replete with lumps of fragrant red," to describe the crab's full but tender white meat and the aromatic eggs which fill its bulging shell. Jia Baoyu also says: "I greedily forget the cold in its belly, the scent on my fingers won't wash away."

Seafood has to be eaten fresh, for it is quick to spoil. Often only a fine line divides freshness from rankness, and Xue Baocha has a different view of the "inner life" of the crab. She complains: "When wine cannot wash away its rankness, we resort to chrysanthemum; to ward off its coldness, ginger is required." The crab's abdomen is full of black and yellow detritus, and when several draughts of wine fail to clear the rank flavor from one's mouth, one has to drink chrysanthemum tea to finish the job. Also, to counteract the excessively "cooling" nature of crab meat (according to traditional Chinese medicinal thinking), it has to be eaten with ginger. Xue Baocha's words reflect the well-known Chinese saying that where gourmet food is concerned, a little goes a long way.

Since Cao Xueqin lived only in Beijing and Nanjing, Chuang Chien-lung surmises that the crabs he ate were lake crabs. Thanks to several hundred years of advertising in The Dream of the Red Chamber, Chinese today still love to eat the Chinese mitten crabs of Jiangsu Province's Lake Yangcheng. Lu Yao-tung recalls how in the 1940s film The Spring Waters Flow East, which is set during the war with Japan, someone talks about "crabs riding in aeroplanes." This refers to how after Jiangsu had fallen to the Japanese, mitten crabs were shipped to Hong Kong and then flown to Chongqing, the temporary capital. Despite the war and the bombing, people could not forget their age-old love for this delicacy.

In ancient times, rivers and lakes did not suffer the eutrophication of today, nor was there competition from introduced fish species such as tilapia. Just like the crustaceans and fish caught in Taiwan's rivers and mountain streams today, the aquatic produce from China's vast lakes and broad rivers was considered no less fresh or tasty than the fruits of the sea. In Taiwan's seafood restaurants, river produce is served alongside marine produce, yet it is consumed with no less gusto by one and all. To eat mitten crabs, some people even fly off to Hong Kong, or set up trading companies to import them.

Seafood in the eastern capital

As well as continuing the age-old tradition of eating oysters and lake crabs, the Song dynasty saw great advances in the making of fishing nets. In Zhejiang, large funnel-shaped trap nets began to be used to catch croceine croaker, and gill nets were used to catch seerfish. When the great shoals of silver-skinned, swallowtailed seerfish came swimming along with the tide, the fishermen would hang out "curtains" to catch them. These "curtains," several hundred feet long, were stretched out between two boats and weighted with iron so that they hung down to the sea bed. The ribbon-like gill nets were placed in the fishes' path, and countless fish were caught in their meshes. "The fishermen of Fujian Province still call gill nets 'curtains' today," says the mainland book A History of the Fishing Industry in China.

As fishing equipment developed, the harvest from the sea grew ever more plentiful. The lobsters caught off the coast of Shandong were said to have rich, full flesh and abundant eggs, more delicious than crab eggs. The family recipes handed down among Confucius's descendants include lobster dishes. Did the Sage eat those selfsame offshore lobsters?

The fishmonger's shops which appeared on city streets in the Song dynasty continued with the method known since the Zhou of using blocks of natural ice to keep their wares fresh. The fishmongers also placed the frozen fish heads, anchovies and croakers shipped from afar into shallow vats of clear water, covered them in willow leaves and hawked them through the streets. In the Northern Song capital Bianjing (modern Kaifeng), restaurants sprang up everywhere, and the food industry became even more "commercialized" as restaurateurs developed numerous fresh fish dishes to cater to southerners who couldn't adapt to northern cuisine. These included "fish souls," made from the lips cut from live sturgeon; "Xi Shi's bosom," made with white fat from pufferfish bellies and named after a famous beauty; and the "gold soup and jade slices" served by Mrs. Song outside Qiantang Gate, which comprised a thick wild rice stem soup and sliced raw common carp and crucian carp. Chefs of the time would serve different parts of a fish dry-grilled, sweet-and-sour and in head-and-tail soup, thus beginning the tradition-still practiced today-of making several different dishes from the same fish.

Crabs no match for clams?

From the Spring and Autumn period to the Tang, a broad distinction already existed between northern and southern Chinese cuisines. In the major cities of Song dynasty China, in addition to vegetarian and Moslem cooking, the food served in restaurants could be roughly divided into four styles: Sichuanese, Shandong, Jiangsu-Zhejiang and Cantonese. Lin Nai-shen writes in his Chinese Culinary Culture that among these four major cuisines the cooking of landlocked Sichuan lacked seafood, but Jiangsu-Zhejiang cooking came from the lower reaches of the Yangtze close to the East China Sea, where both fish farming and sea fishing were well developed. Hence dishes based on river produce were a particularly prominent feature. Canton adjoined the South China Sea, and was rich in both mountain produce and seafood. Shandong cuisine was a product of the middle to lower reaches of the Yellow River, but was also well supplied with predatory carp, crab's legs and surf clams from the Songhua River in the northeast, and with sea cucumber from the Gulf of Bohai and the coast near Haishenwei (now Vladivostok).

In fact, throughout history the chefs of every province have always exchanged ideas and kept themselves up to date. Thus even Sichuan, which has been seen as having little in the way of seafood, was influenced by Jiangsu-Zhejiang cooking and acquired such dishes as "dry-grilled shark fin" and "home-style sea cucumber."

The cuisine of Qing-dynasty Beijing was based on Shandong cooking, and when Wu Weiye of Taicang County in Jiangsu went there to take up an official post, he complained bitterly that he could not eat the fine foods of his homeland south of the Yangtze. He said, "Only a good soup can help me force down a few mouthfuls of rice." Nothing but a soup of fresh surf clams could whet his appetite, but in Beijing there were no clams to go with his wine, nor yet the oysters of his homeland.

It is true that Beijing is some way from the ocean, but having been an imperial capital for many centuries, in Wu Weiye's day it had no lack of fine foods from mountain and sea. If he had only been a little more adventurous: there were no fresh oysters or clams, but as gastronome Tang Lu-sun reminds us, outside Qianmen Gate merchants sold rich, plump, fresh crabs of such exquisite flavor that even Emperor Qianlong was apt to slip out of the Forbidden City in disguise to sample them.

In hock for seafood

In the Qing, seafood was as popular in China as ever. When poet Yuan Mei (1716-1798) wrote his Recipes of the Sui Garden, he noted this popularity, and accordingly included a whole section of seafood recipes.

But what is important with seafood is to bring out its natural flavor, so however many recipes are created they are all designed to make it even more fresh and delicious. As today's bons-vivants put it: "Raw is best, grilled beats boiled." Our ancient ancestors would have known just what they were talking about. The soused prawns and crab eaten in Jiangsu and Zhejiang are submerged in wine and the lid put on. To eat them, you lift the lid, grab a prawn and put it straight into your mouth-still kicking and wriggling.

The "jumping prawns" eaten in Taiwan today may come from a different source and the species may differ from those eaten in days of yore, but the way they are eaten has not changed in a thousand years. In both Japan and Taiwan, fish soup is boiled with only a little shredded ginger for seasoning, and the fish soup of the Tang dynasty was also flavored only with raw ginger and radish. Snack vendors in Taiwan serve seafoods parboiled in water or else grilled or steamed, and accompanied by small dishes of condiments such as soya sauce, raw garlic paste and vinegar to use as dips; this seems no different from the way Oriental weatherfish were eaten back in the Song: after being grilled slowly over charcoal, they were eaten with garlic and vinegar dips.

A poem by You Diao of the Qing records how there were 24 icehouses outside Suzhou's Fengxi Gate, all established to store seafood. During the Qing, eating ice-fresh croaker became very fashionable. Every summer, the fish merchants would go out in huge boats, and shouting loudly would spread their nets to catch the croakers, which they would then transport to the icehouses of Suzhou to await sale. During the reign of the Emperor Kangxi (ruled 1662-1722), Shen Chao, a native of Suzhou, reminisced: "Suzhou was best; in summer we ate fish kept fresh on ice, yellow croaker wrapped in lotus leaves, snow-white shad stuck on willow twigs, and the boats of fish vendors were everywhere." The little boats, marked with small red pennants, would crowd together as the vendors beat gongs and shouted their wares. Some buyers were prepared to pay any price for croaker, and even to visit the pawnshop to raise the funds. Such a passion for seafood seems no less over the top than that of certain people in Taiwan who, when the season comes around, fly off to Hong Kong to eat mitten crab.

Gastronome meets gastropod

In the Song dynasty, China engaged in maritime trade with over 20 countries, and this commerce brought such dried goods as scallops, abalone and mussels to Chinese dining tables. But if we value seafood for its fresh flavor, it does not mean that only food plucked fresh from the sea is "fresh," for the flavor of many seafoods which will not keep unless pickled or dried actually seems fresher than when they really were fresh.

Indeed, it was the fact that abalone, sea cucumber and shark fin need to be dried that helped them to their status as exclusive and eternally fashionable seafoods. In the seafood section of his recipe book, Yuan Mei wrote that sea cucumber "will only be soft if boiled the day before the guests are invited," while hard shark fin required two days' boiling to soften. But abalone was even more recalcitrant: "So tough that it is impossible to bite through; only after simmering for three days does it yield to the knife." Some have said that these dried seafoods do not compare with the fresh variety, but gourmet entrepreneur Chiu Yung-han says that in fact the best abalone is that which has been naturally dried, for "sun drying brings out 'inosite' sugars from the muscle fibers, giving the abalone a unique flavor."

As long ago as the Han dynasty abalone shells were used in Chinese medicine, and a list of 20 fashionable foods in Xi'an eateries which appears in the Western-Han Proceedings of the Salt and Iron Conference (81 BC) includes "abalone in clear broth" and "white-grilled sliced abalone." But except for the large abalone of the region of Dalian, China produced little abalone, and eating abalone did not in fact become a status symbol in China until it was imported from abroad, especially in the 19th century when many Chinese migrated to California to build the railways and mine for gold. The Californian coast abounded with large abalone, and commercially astute Chinese switched to abalone fishing, shipping the gastropods back to be sold in China. This laid the foundations of the Californian abalone fishery.

Today, Chinese in Hong Kong, Singapore, mainland China and Malaysia are willing to pay high prices for abalone and sea cucumber, but because both these creatures have been overfished their numbers have fallen dramatically, and Chinese have been accused of eating everything that swims in the sea from sea cucumber to jellyfish.

In fact, the Spanish also eat sea cucumber. But the Chinese subscribe to the notion that there is no basic distinction between foods and medicines, and ever since Shen Nong tasted the hundred herbs, all manner of weird and wonderful plants and animals have found their way onto Chinese menus.

Furthermore, due to the popular habit of eating certain foods to cure ailments in similarly shaped parts of the body, or simply for their rarity value, shark fins, mitten crabs and abalone, whether of the dry or fresh variety, have all been in vogue at one time or another.

The fresh fresh fish of home

For many people, the question of whether seafood is fresh has little to do with abalone, sea cucumber, shark fins or fish maw, nor with eating foods raw or even alive. What counts even more is the childhood memories they evoke and the nostalgia they awaken for faraway homelands. Seeing news of Taiwan's fishing boats coming back loaded to the gunwales during the fishing season, Tang Lu-sun recalled the hairtail fishing season at Qingdao in his native Shandong. Vast shoals of hairtail would suddenly make the surface of the azure sea shimmer, their silver scales glistening like swirling snow. During this season the fisher folk would eat nothing but fish. In the markets and at temples, hawkers would shuttle through the crowds carrying large steamer trays from which they sold steamed hairtail; when they lifted the lids the aroma would waft everywhere. The piping-hot four-inch sections of hairtail were meltingly tender. Back in the Qing dynasty, Ke Shaomin of Rizhao in Shandong was appointed an official in Beijing. Whenever friends brought him hairtail from home, though rich banquets beckoned, he preferred to stay in and feast on steamed fish.

And doesn't the poem "Mullet" by Sun Wenke of the Ming dynasty sing a very different tune from Zhang Han's eulogy to sliced perch? "My home is in Yuezhou, the sea close by to the east/ The delicious taste of mullet surpasses that of perch."

Just what is "fresh"? What is "rank"? People from the interior think of seafood as being rank, while coast dwellers can never get used to the muddy taste of river fish. Su Dongpo's predilection for fresh fish has been well known down the ages, yet when he was on Hainan Island, he said of the seafood which people in Hong Kong and Taiwan today flock to eat: "When ill, I dread rankness and saltiness-I do not buy their fish." Many people from the interior of mainland China who have lived in Taiwan for 50 years still shake their heads at fish soup garnished with only a little shredded ginger, and complain that it smells off!

Evidently tables groaning under lobsters, crabs and sashimi are not to everyone's taste. Taiwan's estuarine shellfish live on plankton and organic matter, and heavy metals accumulate in their bodies; the fleshy parts such as the foot and adductor muscle can still be eaten, but the central viscera are best left alone. "Even the 'best' seafood today isn't fit to eat," writes Lin Ming-yu, a reporter with the Min Sheng Pao newspaper, lamenting the difficulty of finding good seafood in Taiwan.

What does it mean to eat seafood "fresh"? If eating seafood is part of our culture, then it cannot simply be eating things raw or alive, for otherwise wouldn't the most primitive people be the most cultured?

Looking down at the rolling waters of the mighty Yangtze and up at the bamboo-clad mountains as he rode towards Huangzhou in the year 1080, Su Dongpo composed these lines: "Seeing the river's broad curves, I sense her fine fish/ The slopes swathed in bamboo remind me of their fragrant shoots"-evidently the old boy was already planning his next meal.

Living in Huangzhou, in the company of fish, prawns, deer and a few good friends, Mr. Su would skillfully pluck large-mouthed, fine-scaled mandarin fish from the river, while Mrs. Su would bring out some old wine. No doubt Su Dongpo in his thatched cottage would have echoed the pithy words of a recent TV beer advert in Taiwan: Now that's what I call "fresh"!

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)