Tracing the Roots of Taiwanese Rice

Cathy Teng / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Scott Williams

July 2016

Turn off Taipei’s Roosevelt Road onto Zhoushan Road, then turn again into the National Taiwan University Farm, and you’ll see a small Japanese-style bungalow to the left of the path. Constructed of Taiwania wood in 1925, the building has stood quiet witness to the passing of the seasons on the farm. Through the many years that it served as the NTU Department of Agronomy’s plant breeding room, it was a place where countless scientists prepared for work in the fields. Though the bungalow was never out of use, no one had ever really examined its history until Liu Chien-fu, then a graduate teaching assistant, discovered a pile of manuscripts in its darkroom in 2003. Those documents ultimately revealed the building’s story and the origins of Taiwan’s “penglai” rice varieties.

Liu Chien-fu can have had no idea that he would awaken the general public’s interest in the history of Taiwanese rice when he walked into the NTU Department of Agronomy’s plant breeding room that day in 2003. After all, he was often in and out of the building during his student years. But on that particular visit he happened to come across a book and a pile of yellowing manuscripts, all written in Japanese, in an old cupboard. There was the character ji (pronounced “iso” in Japanese) in red on the cover. “The round ji seal made me think that the documents were somehow related to Eikichi Iso,” says Liu.

Liu immediately informed the agronomy department that he had found what looked like some of Iso’s work. Unfortunately, the department knew very little about the Japanese professor.

Who was Eikichi Iso? Born in Hiroshima in 1886, he graduated from the Tohoku Imperial University Faculty of Agriculture (now Hokkaido University) in 1911. In 1912 Iso came to Taiwan, where he worked for an agricultural research station belonging to the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan. He retired and returned to Japan in 1957 after a 45-year career in Taiwanese rice research.

Iso founded the Taihoku Imperial University Crop Science Faculty, one of the predecessors to NTU’s Department of Agronomy. He was also one of the few Japanese to remain in Taiwan after World War II, though he only taught at NTU for a short time during the post-war era. Instead, he moved to the Taiwan Provincial Government as a consultant on rice production, and was slowly forgotten by NTU.

Cleaning up the “Iso House”

The plant breeding building in which Iso’s texts were found originally belonged to the Advanced Academy of Agriculture and Forestry. A long, wooden structure, it has several rooms, including a rainy-day workshop, a tool storage room, a seed prep room, and a cultivation room. Many agronomy students spent a large portion of their academic career working inside.

The Taipei City Cultural Affairs Bureau designated the building a municipal historic site in 2009. A group of NTU faculty and students went on to establish the Eikichi Iso Historical Association in 2013 to clean it up and turn it into a historical exhibit. They now call it the “Iso House,” and hope it will help them share the story of Taiwanese rice.

The NTU Library took custody of the more than 4,000 manuscripts Liu found and used them to create an Eikichi Iso collection. Hsieh Jaw-shu, a professor emeritus in the agronomy department, spent more than two years organizing and cataloguing them all. He now uses the association’s annual gathering to retell the story of Taiwanese rice.

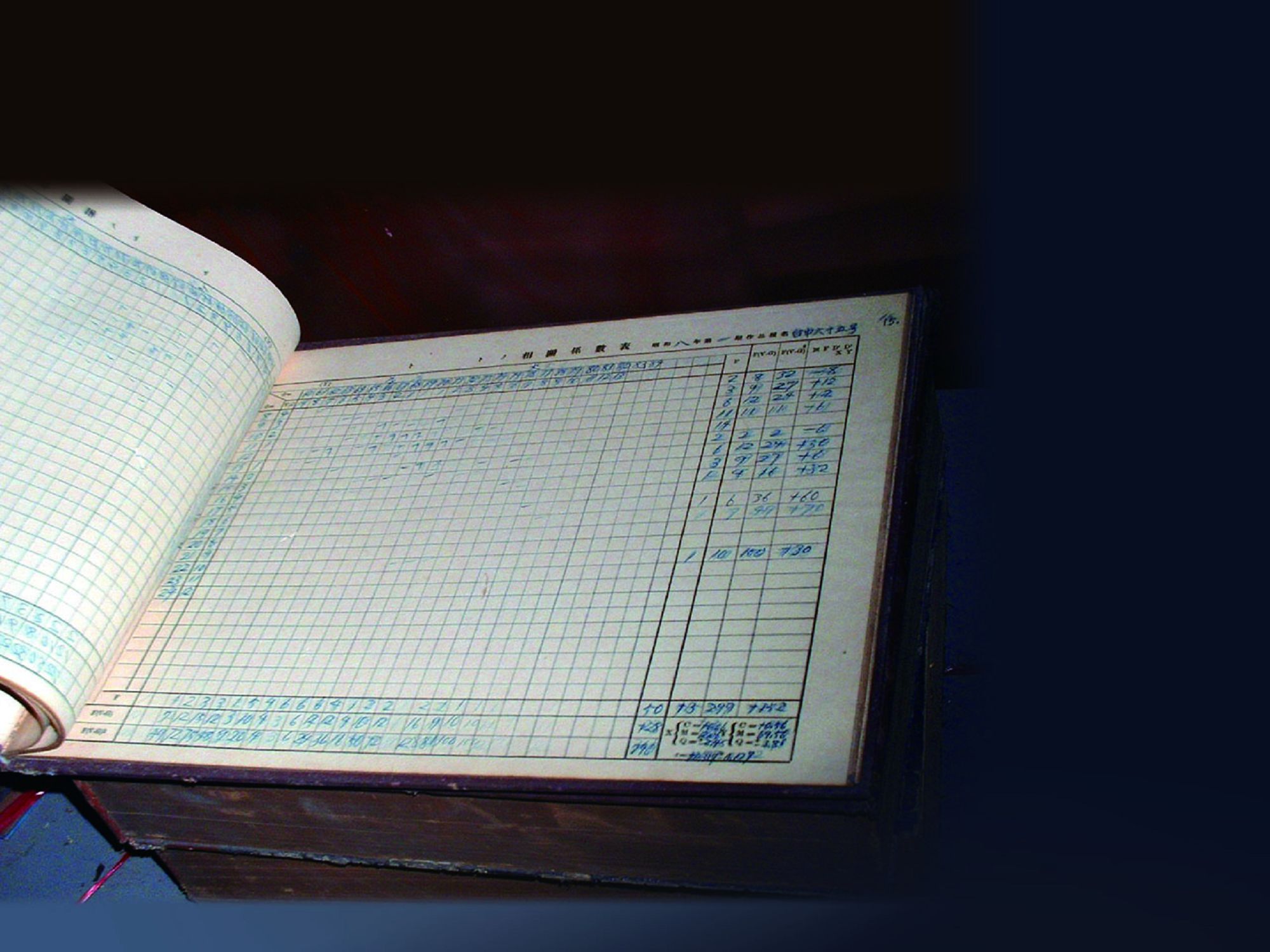

The Eikichi Iso Historical Association has renovated a portion of the Iso House and turned it into a museum for the records of Iso’s experiments. Displays include rice samples, old-fashioned laboratory equipment, and experiment logs. (inset photo courtesy of Iso House)

Japonica vs. indica

The Japanese had a slogan during the period they ruled Taiwan (1895–1945): “Agricultural Taiwan, industrial Japan.” They brought several varieties of Japanese rice to Taiwan and began working to improve them in hopes of developing a variety that would grow in Taiwan, but suit Japanese tastes. These “japonica” varieties produced rounder grains than the “indica” varieties already grown in Taiwan, whose grains were longer and firmer. The japonicas also had a chewier texture and a somewhat stickier mouthfeel.

In those days, there were two schools of thought among Japanese rice experts in Taiwan. The first, led by Bunzo Hashiguchi (1853–1903), director of the Production Industries Division of the Japanese colonial government, advocated importing and improving Japanese rice varieties. Yoshiharu Fujine (1864–1941) carried on Hashiguchi’s vision by introducing Japanese rice into Taiwan after Hashiguchi’s passing.

Japanese rice grown in Taiwan had a serious problem: it flowered too early. Hoping to overcome the issue, scholars sought out places in Taiwan with a climate similar to Kyushu’s to conduct their research. They settled on locations in the mountains near Taipei, including spots in the areas around Zhuzihu, Tamsui, and Jinshan. Although scientists achieved good yields in the mountains with the Nakamura and Edo japonica varieties, their efforts to grow japonicas on Taiwan’s plains utterly failed.

The other school, led by Tsune Nagasaki (1864–1939), advocated improving Taiwanese rices. Their primary contribution to this endeavor was eliminating weedy rice from Taiwan’s indica strains. These indica rices happened to include a variety called Tuan-Kung-Hua-Lou that was similar in appearance and proportion to the Japanese rice. Researchers had hoped to use it to achieve their breeding objectives, but their progress stalled when they couldn’t find a way to improve its flavor.

Iso joined the Taichu (Taichung) Prefecture agricultural research station in 1914 as a rice improvement technician. Here he met Megumu Suenaga, who would become his research partner.

Iso and Suenaga chose to continue work on japonicas even though the Office of the Governor-General had made it clear in 1910 that it wouldn’t reward such efforts.

Iso focused on 17 characteristic traits of the 547 indica varieties the Governor-General’s office had recommended for cultivation, using the Nakamura japonica as a control.

His work showed that Tuan-Kung-Hua-Lou’s shape was unique among the indica rices and its only point of similarity to japonica varieties, shattering the Tsune Nagasaki school of thought’s dream of creating indicas that taste like japonicas.

The Eikichi Iso Historical Association has renovated a portion of the Iso House and turned it into a museum for the records of Iso’s experiments. Displays include rice samples, old-fashioned laboratory equipment, and experiment logs. (inset photo courtesy of Iso House)

The introduction of penglai rice

With the support and encouragement of Iso, Suenaga proposed a new method for transplanting seedlings in 1923. By shrinking the time spent cultivating seedlings and by delaying flowering, he changed the plant’s life cycle and solved the problem of japonicas flowering too early in Taiwan’s climate.

His method, which used Nakamura rice, proved that at least one japonica could be grown on Taiwan’s plains using improved farming methods. As Liu says: “The Nakamura variety established a beachhead for japonicas in Taiwan.”

At Iso’s suggestion, in 1926 Governor-General Takio Izawa dubbed japonicas grown in Taiwan “hōrai” rice (penglai in Mandarin, also spelled ponlai). The name comes from Mt. Penglai (Mt. Hōrai), a fabled land in Chinese and Japanese mythology that is sometimes associated with Taiwan.

Suenaga continued crossbreeding varieties of japonica and in 1929 succeeded in producing “Taichung 65,” a flavorful, adaptable, high-yield rice. It became the most widely cultivated rice in Taiwan, and at one time was grown commercially in Japan, the Ryukyu Islands, Nepal, and Iran as well.

The research conducted during Iso’s day provided Taiwan’s wet rice cultivation with a scientific foundation. Later scholars built on that foundation, improving the flavor, aroma, and quality of Taiwanese rice varieties. But until recently no one really knew the history of penglai rice and its connection to place.

In that period the Zhuzihu area of Yangmingshan was an ideal location for producing seed stock: its climate resembled that of Kyushu and its topography made natural cross-pollination unlikely. The Japanese began producing seeds in the area in 1921, and established the Zhuzihu Seed Farm in 1923.

But Zhuzihu switched to cultivating alpine vegetables, calla lilies, and other cash crops after harvesting its last parcel of paddy rice in 1976. No rice has been grown there commercially in 40 years.

It was only after the Taipei City Cultural Affairs Bureau’s designation of the Beitou Granary, the Iso House and the Zhuzihu Penglai Rice Seed Farm as historic sites that Zhuzihu residents realized they had such a precious cultural asset. They responded by founding a club aimed at reviving local rice cultivation. The club is also working with the food and agriculture programs of two nearby elementary schools to get kids into the fields to do a bit of farm work. Walking backwards and bent over while transplanting young rice plants into the paddies, the kids grasp for themselves the origins of the saying, “backing up is actually moving forward.”

Pong Yun-ming, secretary-general of the Eikichi Iso Historical Association, has worked hard to preserve the house, which was ground zero for the development of Taiwan’s penglai rice.

Nakamura comes home

Nakamura comes up frequently in the context of Taiwanese penglai rice. Suenaga’s seedling transplantation method made it possible to grow Nakamura rice on Taiwan’s plains, but the variety was vulnerable to rice blast and soon disappeared from Taiwanese paddies.

In 2013, the Eikichi Iso Historical Association made a goal of bringing Nakamura rice back into cultivation. The association obtained ten Nakamura seeds from Japan’s National Institute of Genetics, but the seeds, which had been frozen for 30 years, failed to germinate. The institute gave the association another 50 seeds in 2014, three of which germinated. Planted in front of the Iso House, they were harvested in the fall of 2015.

Nakamura rice returned to Zhuzihu in 2016. Members of the Iso association transplanted seedlings to the paddies in April. By June, those seedlings had grown to 30 centimeters in height. While the harvest is still a few months away, Nakamura rice has come home at last. This homecoming is important because it spotlights a crucial period in the history of Taiwanese rice, and honors all the people who committed their lives to its development.

“Who knows how much hardship went into each grain of rice that we eat?” Once you grasp the history of Taiwanese rice, you realize that the “hardship” in every grain extends beyond the farmers to the scientists and plant breeders who devoted decades of their lives to its development. The next time you hold a bowl of rice in your hand, be sure to savor the delicious flavor that took so very much effort to create.

This tableau in the Zhuzihu Ponlai Rice Foundation’s Seed Field Story House depicts a farmer stripping ears of rice by hand to obtain seed grain.

The Story House recreates a 1916 scene at the Taichu Prefecture agricultural research station. Eikichi Iso is on the right, dressed in white. Megumu Suenaga is seated on the left, dressed in black. Their efforts were crucial to the development of penglai rice.

The Nakamura strain of japonica rice returned to Yangmingshan’s Zhuzihu, its first home in Taiwan, on a drizzly day in the spring of 2016. Professor emeritus Hsieh Jaw-shu (center) drove the effort to restart cultivation of Nakamura rice. (photo by Huang Xizhu, Iso House)

Nakamura rice growing in front of the Iso House.

City children rarely experience holding an ear of rice in their hands, stepping into the soft mud of a paddy, and walking among rice plants nearly half as tall as they are. But that’s exactly what the children of Wego Elementary School are doing as part of their farming internships. (courtesy of Wego Elementary School)