“We want a better democracy, a fuller democracy with compassion and loving kindness…. Values like love and compassion should be part of politics because justice must always be tempered by compassion.” This is the hope expressed by Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of the democratic movement in Myanmar.

Refined, learned, elegant, charismatic, with tremendous leadership skills and even a sense of humor, Aung San Suu Kyi spent decades under house arrest for opposing the Myanmar regime. She was finally released after the general election of November 2010. She has made her contribution to political reform in Myanmar with a combination of gentility and endurance that could be considered a distinctively female approach to resisting authority. This heroine, who was recently praised as “the conscience of a nation” when she went to Norway to receive her Nobel Peace Prize, is today a major force for world harmony.

Women are today a powerful force in politics around the globe, and openness to women’s participation in government is one of the primary indicators of structural change in a society. Though women politicians in Taiwan have gotten into office through different routes—some through their politically powerful families, others standing in for victims of repression, others through professional expertise, and others through fresh and clean images—together they have staked out a solid claim in the world of politics for a worldview and wisdom that are uniquely female, and created new space for the sharing of government power between the sexes.

The Oscar-winning film The Iron Lady depicts the struggles and inner world of former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher; it has generated worldwide sympathy for this pivotal figure, the first woman prime minister in British history.

Thatcher started her 10-plus years in office with the British economy in decline, and her market-oriented reforms created enormous controversy.

After years of turmoil, finding herself at ideological odds with her own cabinet and faced with a popular anti-tax movement, Thatcher ultimately resigned. But this tough and dominant personality has remained an inspiration to aspiring women political figures everywhere.

Women in Taiwan have even begun to make headway in the military, traditionally the most male-dominated realm of all. The photo shows Army Colonel Ting Liang-jen (second from left) the first woman to head up a branch of a combat field unit.

In recent years it has become increasingly common in many places around the world to see women in the highest positions of political power. According to a study released in March of 2012 by the UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (a.k.a. “UN Women”) and the Inter-Parliamentary Union, at the time of writing there were 17 women presidents or premiers worldwide, compared to only eight in 2005, and the percentage of women ministers had risen from 14.2% in 2005 to 16.7%. Scandinavian countries had the highest percentage of female ministers (48.4%), while the Americas (21.4%) were second.

Taiwan can be proud of the fact that in terms of gender equality and participation by women in politics, it is not only keeping pace with the international community, but has even been setting the standard for achievement in Asia.

One of the main indicators used to weigh women’s political and economic power is the “Gender Empowerment Measure,” with the item “seats in parliament held by women” being one of the most widely watched numbers.

Statistics from 2009 show that in Taiwan the percentage of seats in parliament held by women rose from 21.5% in 2003 (ranked 40th) to 31% in 2009 (16th). This figure put Taiwan well ahead of Singapore (24%, 34th), the Republic of Korea (14%, 70th), and Japan (12%, 77th), and even ahead of long-established democracies like the UK (20%) and US (17%). (See Fig. 1.)

However, the raising of women’s status in the decision-making centers of government has gone more slowly. Before 2000, only a few women had ever served as ministers. In 2000, the DPP won the presidential election, bringing to power president Chen Shui-bian and his female vice-president Annette Lu. This marked the beginning of a new era of more equal gender participation in government, and the percentage of women in the cabinet leaped to 25%. Since then the figure has been in the 15 –25% range.

Are there any special features that distinguish Taiwan’s model for participation by women in politics? Have the times made the heroines? Or the heroines the times?

Looking back, in the early days women who got involved in politics in Taiwan fit the same basic type as in most less developed countries, but in the wake of the development of civil society, social activism, and political parties, women political figures have become increasingly self-made and diversified.

Li Ming-juinn, director of research at the Taiwan Brain Trust, points out that in almost all countries participation in politics by women only got started in the 1950s, but that the career paths of women in developed countries have generally differed from those in developing countries. Though female leaders have emerged in Latin America and Southeast Asia, almost all have been successors to powerful male relatives or spouses. (This is not, of course, to take away from the courage and sense of responsibility they have displayed, often under repressive conditions.) In contrast, women have been able to succeed in politics in North America and Europe largely because of their individual skills and expertise.

Taiwan today has in common with advanced democracies government by competing political parties, but also inherits the traditional Asian emphasis on family. Even today political clans can be a powerful resource for aspiring female politicians, though this by no means should obscure any individual’s personal commitment, determination, and/or ability.

Following the supplementary legislative elections of 1989, eight women legislators from the Kuomintang organized their own caucus, a tough and well-informed elite group that made quite an impact on the political scene back then. From left: Chou Chuan, Chu Fong-chi, Hsiao Chin-lan, Hung Tung-kuei, Hung Hsiu-chu, Ko Yu-chin, Shen Chih-hwei, Wang Suh-yun.

Ma Wen-chun is currently a Kuomintang legislator from Nantou County. She started her political career back in 1994 when, at only 29, she was elected as an independent (non-party) county assemblywoman. Her father, Ma Rongji, was a long-serving local politician, serving in turn as a member of the Puli Township Council, mayor of Puli Township, and a provincial assemblyman. Wen-chun reveals: “I had never sought a political career. It’s just that at that time my father unexpectedly passed away, and the election was scheduled to come only a month after the funeral. His supporters were very insistent, so my only option was to grit my teeth and jump into the race.”

Ma had previously limited herself to being a silent bystander to the dedication shown by her parents. (Though only her Dad was elected to office, her Mom worked side by side with him serving local voters.) Wen-chun, after being elected herself, didn’t disappoint her constituents, and at age 37 she was elected mayor of Puli. In her eight years in office she led Puli’s re-emergence from the disaster of the September 21, 1999 earthquake and its repositioning as a center of the recreational farm industry. In 2009, running under the KMT banner, she won a by-election for the Legislative Yuan, and she was re-elected in 2012.

“The greatest lesson I learned from my father was to not fear those in authority, but to persist and do the right thing,” says Ma, in a self-evaluation. “But I am at my best when I can bring into play the feminine traits of softness and accommodation, rather than always butting heads and refusing to compromise.”

Incumbent DPP legislator Hsiao Bi-khim, like Ma, got into politics at an early age, but her career has followed a very different route. She started out by working as a party official, then moved into a trusted position in the executive branch of government, before finally getting into an elective office.

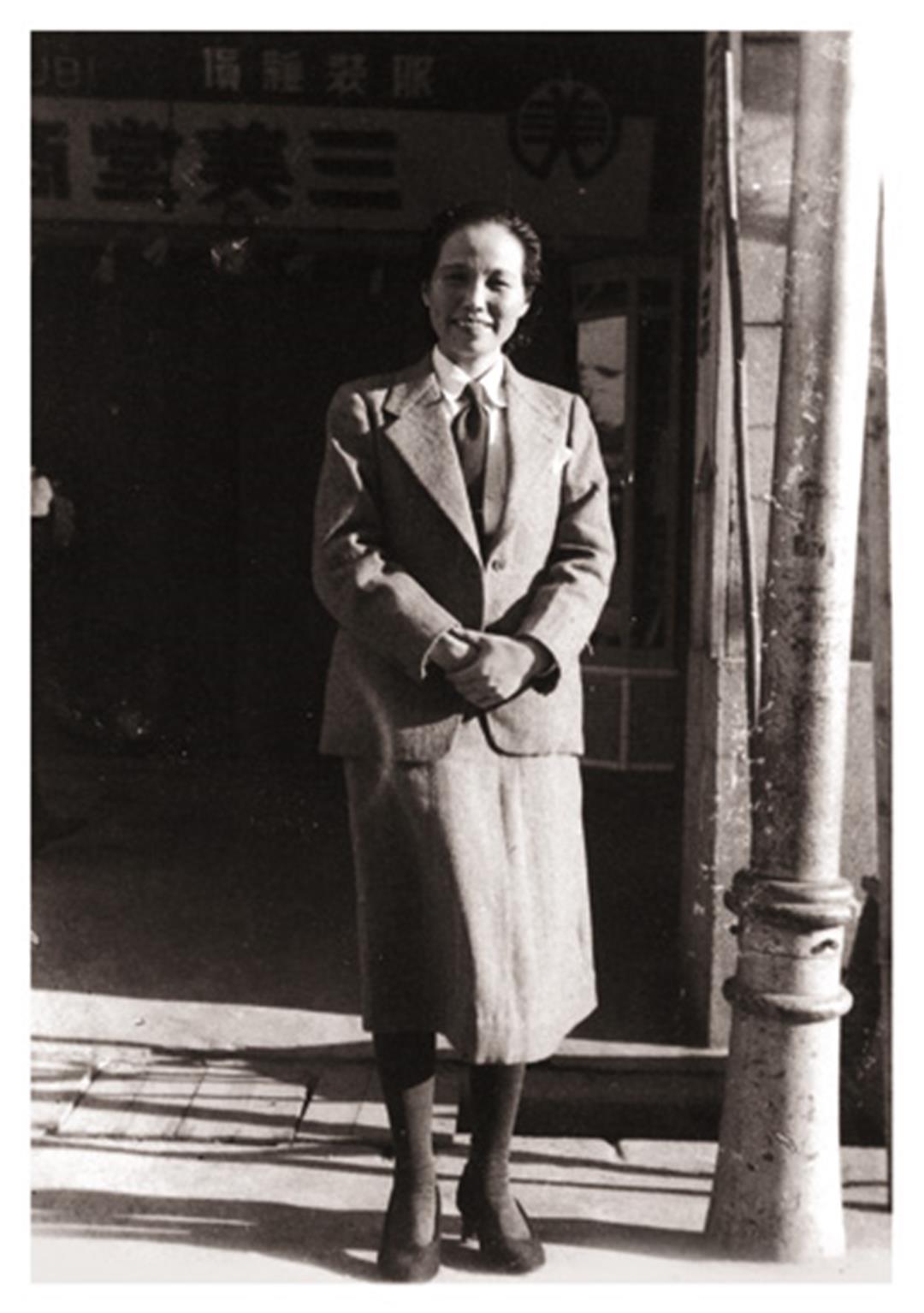

Holding an MA in political science from Columbia University and having a multi-ethnic background, she attended both high school and university overseas. But she closely followed the history of Taiwan’s democratic movement, and was profoundly inspired by important women political figures like Xie Xuehong, Annette Lu, and Chen Chu. At the age of only 26 she was named director of the DPP’s Department of International Affairs, and since then she has devoted most of her attention to promoting international relations. She is also one of the party’s most important experts on cross-strait affairs.

Aung San Suu Kyi (right), the leader of the democratic movement in Myanmar, has been an inspiration to countless other women to get involved in politics. Recently several women leaders from the Democratic Progressive Party, led by legislator Hsiao Bi-khim, personally visited Aung San Suu Kyi to express their respect and best wishes.

The high success rate of women in politics in Taiwan is inseparable from the systemic reforms promoted for so many years by the women’s movement and academics.

Fan Yun, an associate professor of sociology at National Taiwan University, says that the women’s movement invested a lot of energy in breaking down structural factors underlying gender inequality. In politics, besides keeping a close eye on the political parties to ensure that they kept their promises of bringing more women into government, activists also successfully promoted reforms in the electoral system that would benefit women.

Fan Yun explains that many advanced countries have adopted quota systems as pro-active corrective measures, which can be applied to both elective offices and positions in the executive branch. The purpose is to increase opportunities for women to participate in politics and achieve substantive power sharing.

In Taiwan’s case, the ROC constitution had long stipulated a 10% quota for women in all elective bodies, but since the 1990s women’s groups in Taiwan have been actively pushing to far surpass that figure. While the idea of amending the constitution itself is not on the table, in 1999 the new Local Government Act set a quota of 25% of elective seats for women at the local level, and there are still hopes of raising that figure to one-third.

In practice, women have surpassed the 33% level in city councils of special municipalities and, most importantly, at the level of the central government, women account for 33.6% of legislators in the current (8th) Legislative Yuan. This is the highest percentage in history. (See Fig. 2.)

The Green Party was the first party in the world to have at least one-third of its nominees in any given election be women. This photo was taken at an event hosted by the Taiwan Green Party for environmental activists from all over Asia.

The ROC legislative election system includes at-large seats, with each party nominating a slate of candidates who are then assigned at-large seats according to the party’s proportion of the total vote. This allows parties to nominate people who transcend factional or regional power bases, bringing more diversified voices into the parliament. The rules also require that one-half of all at-large seats for any given party go to women. Over the past two elections, this has become an important entrée for forward-thinking and intellectual women to find places in the Legislative Yuan.

KMT legislator Lo Shu-lei, first elected to an at-large seat in 2007, is an accountant by profession, and has all the characteristic traits of that trade—pragmatic, hard-headed, meticulous, trustworthy. She has become known for her close scrutiny of the budget, winning accolades for her role in a number of prominent cases: the “fat cats” at the Financial Supervisory Commission, phony promissory notes at the Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation, and falsified reporting at the Aerospace Industrial Development Corporation. She has five times been cited as an outstanding legislator by Citizen Congress Watch, who also named her the top-ranked member of the legislature’s finance and transportation committees.

However, she has also become isolated within her party in recent times for her straightforward comments on two controversial issues—the increase in fuel and electricity prices, and the dispute over imports of beef from the US. “A lot of people think that legislators from the same party as the president should just be a rubber stamp for the executive branch, but this is unacceptable. I came into the legislature determined to protect the general good. I have no interest in fame or fortune, and seek only to keep a clean conscience.”

Lin Shih-chia just took office as an at-large legislator for the Taiwan Solidarity Union. Her rebellious spirit has grown out of many years of social activism. For more than a decade now, she has flown to the annual meeting of the General Assembly of the World Health Organization in Geneva every year, wearing a vest emblazoned with the word “Taiwan,” representing the Medical Professionals Alliance in Taiwan, to protest and observe on the margins of the meeting site. This May, in her status as a legislator, she finally got into the meeting itself, but because of the “sensitive” wording on her vest, she was asked to leave. But she does not feel it was a waste of time, for in a democratic society it is completely normal for people to express their opinions.

Yang Wan-ying, professor of political science at National Chengchi University, says that traditionally men have held the rudder in politics, which has been infused with paternalistic traditions and ideas, and of course these are tied into complex sets of interests and struggles over resources. The only way to relax the grip that paternalistic ideas and interests have on politics is for women to hang in there, and deepen their participation over time.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Margaret Thatcher was way ahead of her time, smashing through the dual barriers of gender and class to reach the summit of power. The photo comes from the biopic The Iron Lady, with Meryl Streep playing Thatcher.

Although on the surface politics are now open to women, the fact is that women trying to make a career in politics still face a lot of obstacles.

Fan Yun says that society still fails to affirm and respect women’s abilities. If a man simply occupies a high-status position, people rarely question his ability, but when women gain positions of power, they are still looked at skeptically and must prove themselves constantly. For example, it has been said: “Anyone in a skirt will never make a good commander-in-chief” (referring to the president’s role as C-in-C of the armed forces).

Women who achieve higher-ranking positions in the civil service are also held back from opportunities for further promotion, compared to their male colleagues, by expectations that they should play a bigger role in taking care of their families.

Also, Taiwan society has always had a moral bias and strong sense of voyeurism with regard to women in politics, which intimidates many women from getting into political life.

Yang Tsui, a professor in the Department of Sinophone Literatures at Dong Hwa University, says that there is a double standard in society toward gender and power. Men who are ambitious for power are seen as “staying aggressive out there,” as showing admirable masculinity and toughness, but a woman who aspires for power is often subconsciously seen as “showing the ugly side of her character,” or is even demonized.

“The tactics for demonizing women are very obvious in the authority structure,” says Yang Tsui, pointing to the following example: Xie Xuehong (1901–1970) was one of the pioneers of political activism by women in Taiwan. She became politically active in the 1920s during the May Fourth era, later joined the Taiwanese Communist Party, and after the February 28th Incident of 1947 was forced to flee to mainland China. She was portrayed by the authorities in Taiwan as avid for power, material gain, and sexual pleasure, as a “demon seducing the country.” Or consider the fact that many women opposition leaders in the Third World, forced by circumstances to separate from their families, have then been accused by the authorities of failing as mothers and lacking in love for their families.

But there are obstacles faced by women in politics that are well nigh immovable. These are mainly in the difficult-to-discuss realm of inequality in “private life.” “It is said that behind every great man is a woman, but when women get involved in politics, they don’t expect to have any man to back them up—it’s enough if the man simply doesn’t clog the road forward!” quips Fan Yun.

Legislator Ma Wen-chun relates that if she has a meeting or legislative session in Taipei, she insists on returning home to Nantou at night no matter how late the hour, because “I at least want my children to be able to see their Mom when they get up in the morning.” She is also grateful to her mother and husband for helping out with many household responsibilities. Legislator Lin Shih-chia, who has two toddlers (one son, one daughter), is happy to be an at-large legislator because she does not have to spend her evenings serving district constituents, and is also thankful to have a husband who treats her as an equal. The only hitch is that her husband, a professor well versed in feminism, sometimes says to her when they argue: “Don’t be using those political infighting tactics with me!”

The brash political and social commentator Ellen Huang, who has been active in political circles since the early 1980s, when opposition parties were still illegal, says: “It is backward thinking to ask women political figures to ‘explain’ themselves or ‘apologize’ for being single. Is it even remotely possible that being single can affect the public interest? If so, all state institutions should have special matchmaking departments; otherwise, shut up about it!” She says that in modern society remaining single is a matter of choice, not a matter of right and wrong. “For women in politics remaining single is a choice allowing them to devote themselves more fully to their duties.”

“Gender equality means allowing everyone to live a life of value.” Feminist pioneer Ellen Huang has dared to dream and has become an iconic figure in her own right.

One of the most interesting questions related to the history of women in politics is whether having women leaders will automatically bring changes of priority or method to political decision-making and society as a whole.

Back in the 1980s, some intellectuals theorized that women have different moral values from men, that they devote more attention to interpersonal relationships, responsibilities, and concern for others. Men, the argument runs, invest more in competition, success, and the protection of individual rights and interests. This distinction, reflecting different socialization processes, means that men and women may very well have different perspectives on politics, with correspondingly different behaviors and priorities.

For example, Huang Chang-ling, an associate professor of political science at National Taiwan University, says that research in Taiwan has found that corruption at the level of township politics is closely intertwined with the male culture of heavy drinking parties at hostess bars. Therefore an increase in the percentage of women in local politics could reduce the opportunities for corruption.

However, these days feminists are less inclined to see differences as resulting from the “nature” of men vs. women. “If women are able to alter traditional political culture,” Huang elaborates, “it will be because they promote a more reasonable and transparent distribution of resources and power.”

Fan Yun believes, on the other hand, that women are still able to come up with public policies that have a gender consciousness. For example, Wu Jiali, whose background was in the women’s movement, promoted gender equality reforms in state examinations for the police, foreign ministry, and other agencies, when she served as a member of the Examination Yuan, making it more possible for women to cross over into many professions for which they had previously been considered unsuitable.

“From the point of view of the women’s movement,” says Fan Yun, “the goal for the next stage could be for feminists and political activists to work toward challenging the economic mindset of marketization and reshaping the future outlook for the country.”

Politics and women, goes one comparison, are like guns and roses. In this metaphor, women may look disarmed, but by applying intelligence and flexibility, they have successfully stormed many a fortress in the history of politics. Let us look forward to a future in which men and women govern side by side, where democracy and equality are more than just words, but are part of the everyday practice of government.

The election of Chen Shui-bian as president and Annette Lu as vice-president back in 2000 was a milestone for participation by women in the decision-making center of power.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)