In the late 1980s, when a great number of people plunged into the soaring stock market and speculated on real estate, some called Taiwan "Greed Island." Over the past two years, there have been a series of deadly fires in public places, prompting the nickname "Fire Island." Recently, because the long-term problem of final disposal of garbage has never been resolved, towns seem to be competing to dump their waste on top of each other, inspiring some to dub Taiwan "Trash Island." Early this year, a British citizen in a custody battle with his Taiwanese ex-wife claimed before a British court that Taiwan is "unfit for human habitation."

"Ilha Formosa." In Portuguese it means "Beautiful Island," and for a long time it was the name used by the international community for Taiwan. But is seems this name has been obscured of late by a flurry of more negative monikers.

Why did 16th century Portuguese sailors exclaim "Beautiful Island" upon seeing Taiwan? What exactly was "formosa" about Formosa? How has this beauty fared over the past 400 years? Faced with unflattering new nicknames, can we perhaps gain some food for thought about where Taiwan's natural beauty has come from and where it is going by looking back on Formosa?

A metal construction fence rings a site on the sand dunes just behind the seaside at Yenliao on Taiwan's northeast coast. The view of the dense forest which flanks the northeast coastal highway is blocked off here by the ongoing construction.

This June, the long-stalled budget for the Fourth Nuclear Power Plant finally passed the Legislative Yuan. Work on the plant, long shelved, was once again taken up in earnest. On sand dunes once held together by a mixed variety of trees, excavators pile up earth to raise the land to a height of 12 meters above sea level. This is to prevent possible damage to the nuclear power plant should there be a tsunami thrown up by an earthquake.

The northeast coast has become one of the most popular tourist destinations for people in northern Taiwan. The 70-km-long coastline is highlighted by fascinating natural features carved by Mother Nature using shifting seasonal winds, sea erosion, and volcanic eruptions. The nuclear power plant, covering 48O hectares, before long will have supplanted the abandoned Chinkuashih copper mines as the most prominent manmade landmark on the coast.

Going west along the northeast coast for an hour or so you come to Chinshan Rural Township, which is actually the north central part of the coast. This is where Taiwan's northernmost mountain range, the Tatun Mountains, runs into the sea. As such, with its view of a wide expanse of water and green coastal ridges, the area is said to have especially auspicious geomantic properties. Thus the hillsides are covered with cemeteries advertised as "Fit for an Emperor or King," "Home of the Dragon and Den of the Tiger," or "Paradise." For businessmen to build these cemeteries--the most expensive and delightfully-sited on the island--they had to first level the mountainsides and uproot the woods.

Economic development is changing the face of Taiwan's northern and northeastern coasts, where the coming together of mountains, plains, sea, and sand have created some of the island's most interesting scenery. Of course there's nothing peculiar about development transforming parts of Taiwan. What is special in this case, however, is that the northern coast is, in the view of many scholars, the very place which inspired the name "Formosa," the appellation by which Taiwan was known in the international community.

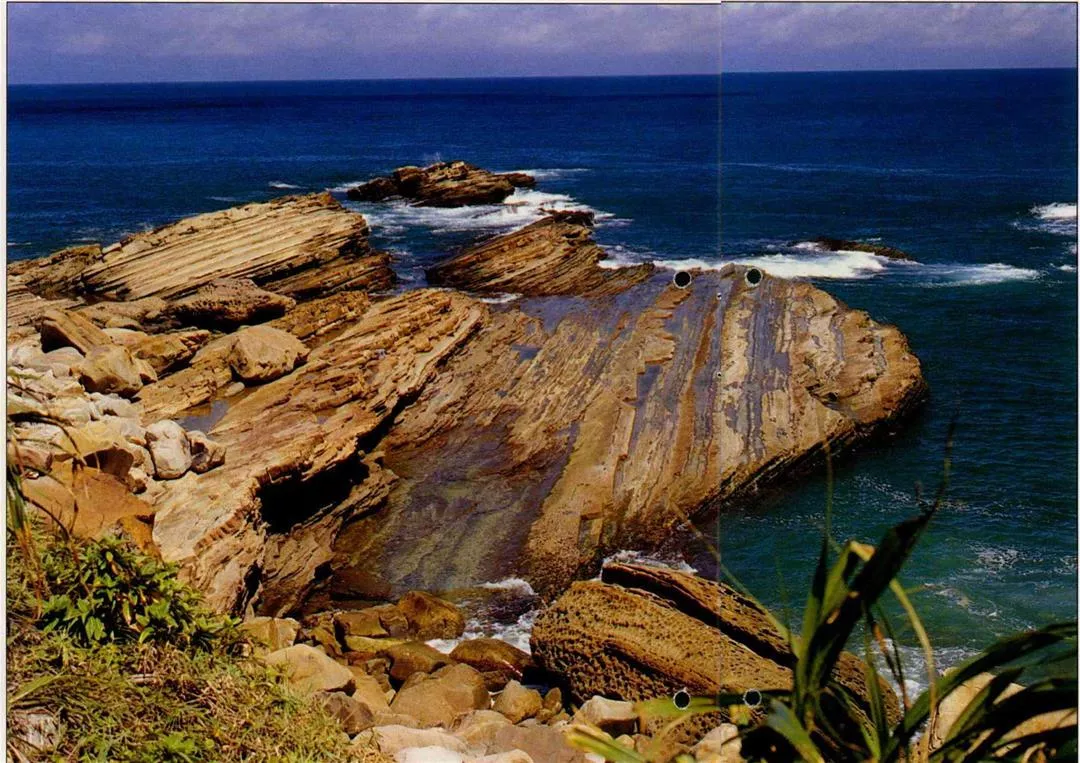

The topography of the northeast coast, shaped by sea erosion, is unique.(photo by Cheng Ying-sheng)

What a beautiful island!

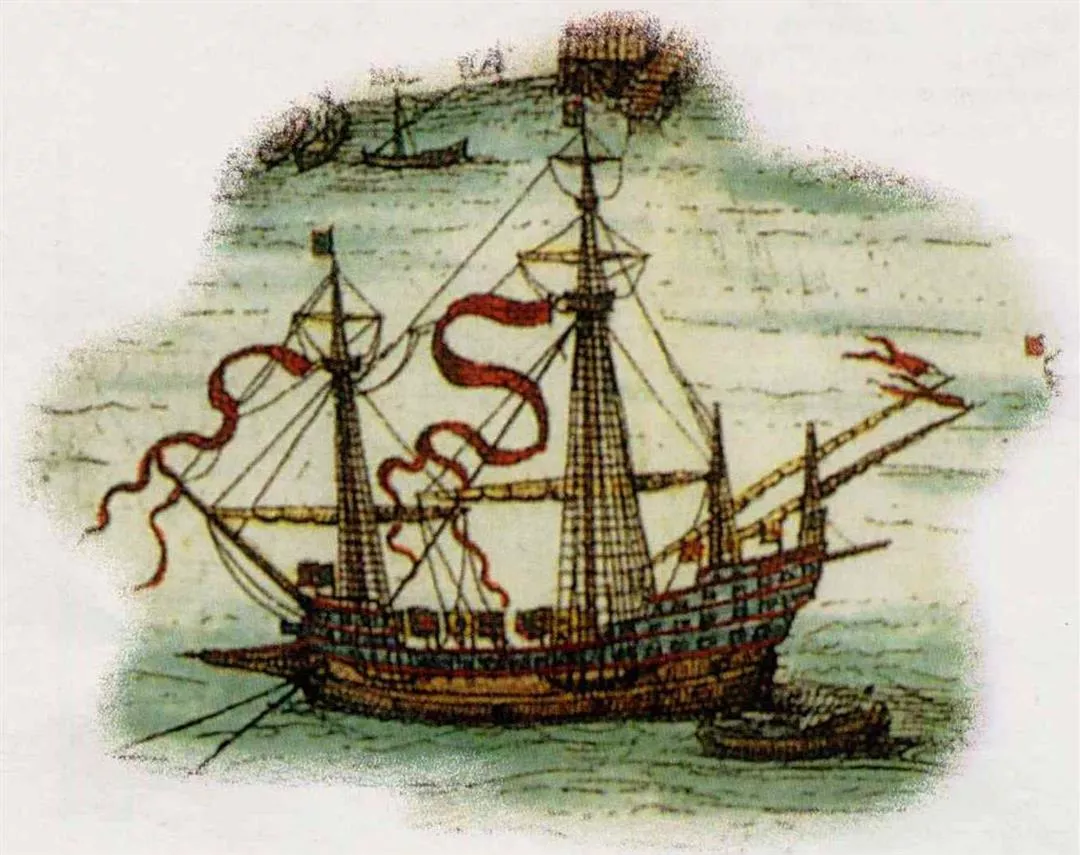

In the mid-16th century, Portuguese sailors were utilizing new navigational techniques to explore the globe. "As they sailed north from the South China Sea, to the starboard side they suddenly saw a splendorous island rising out of the waves. Some sailors were so astonished that they blurted out, 'Ilha Formosa!' [What a beautiful island!]"

This story, as recorded in the diary of an official of the Japanese occupation era, is familiar to virtually all of Taiwan's residents.

The question here is this: Precisely which part of Taiwan was it that the Portuguese sailors saw that inspired the name Formosa, a name that would last 400 years?

Europeans had been fascinated with the legendary beauty of the Orient ever since Marco Polo's diaries of the 13th century and the spread of stories about the splendor of Japan's golden temples and religious statuary. Intrepid explorers and businessmen took their crews across the vast oceans to the mythical "golden isles" of the Far East.

At that time in China, the Ming dynasty was at its height. The imperial court had banned coastal trade, only permitting foreign missions to bring "tribute" to the capital. But more and more foreign ships appeared on the coast, and both Western traders and local pirates greedily eyed Chinese silk, tea, and porcelain, as well as Indian pepper and ivory, and a variety of exotic products from Southeast Asia.

Wong Chia-yin, a lecturer in the Department of History at National Taiwan University, points out that the South China Sea was the prime route for trade and smuggling between Europe, Southeast Asia, China, and Japan, and Taiwan found itself on this maritime highway.

Back then Taiwan was known as "Little Ryukyu" among the Chinese, and it was only the Portuguese who christened it Formosa. When Taiwan was drawn onto Western seafaring maps as "Formosa," the name became the most common appellation used for this island among Western nations. Even today it remains a virtual synonym for Taiwan.

Twelve Formosas?

Yet, as anyone familiar with 16th and 17th century history will tell you, Taiwan wasn't the only place called "Formosa." Hsu Hsueh-chi, a researcher in the Institute of Modern History at the Academia Sinica, reminds us that the whole world looked fresh and exotic to those intensely curious early adventurers, and they called many of the places they saw along the way "Formosa," which after all to them merely meant "beautiful," and therefore did not refer to any particular location. According to the book Kumen de Taiwan by Wang Yu-teh, there were more than a dozen places tagged Formosa in those days, including spots in Central America, Asia, and Africa.

Yet today, when you flip to the entry for "Formosa" in the Encyclopedia Britannica, only Taiwan and a province in northern Argentina are identified with this word. And, as botanist Huang Juei-hsiang (now director of the Office of Agriculture of the Taipei Municipal Government) notes, the name Formosa is only used in the academic names of those plants that are especially beautiful or which originated in Taiwan.

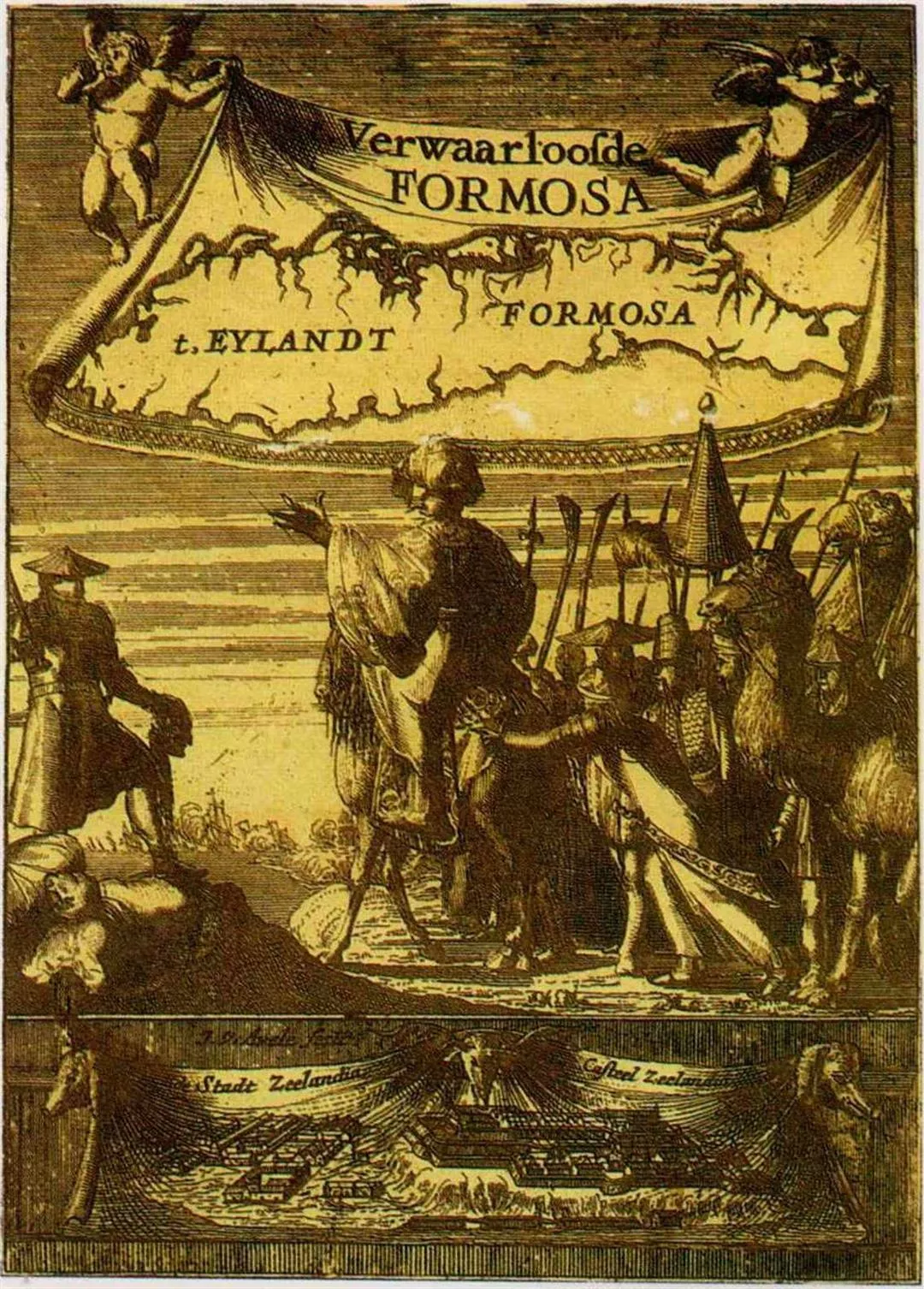

So why has this one word, carelessly bandied about, stuck to Taiwan? Liu Ko-hsiang, a veteran nature observer and explorer of old trails in Taiwan, argues that the answer is to be found in history. He says that it is related to the expulsion of the Dutch from Taiwan by the Chinese general Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) in the 17th century. "Zheng was the first one to push Westerners out of the South China Sea, so the name Formosa made an especially deep impression on Westerners. Thereafter, Western historians often referred to the story of Koxinga and the Dutch, spreading the name Formosa among Western historians." In fact, even in the 17th century the Dutch had already published a number of documents on Taiwan. The most famous was written by Frederic Coyett, the last Dutch governor and the man defeated by Zheng, and it has long served as an important source about Taiwan for historians.

Perhaps Taiwan has hung on to the name Formosa for historical reasons. But that doesn't mean that the name wasn't deserved in the first place!

This 17th century Dutch book Verwaarloosde Formosa gives a detailed account of the Dutch withdrawal from Taiwan. The text remains important for studies of Taiwan's history. (photo courtesy of the Southern Materials Center)

North by northeast

In the spring of 1875, a Canadian doctor and missionary named Mackay sailed to the mouth of the Tanshui River for the first time. As the ship sailed upstream, he stood silently upon the deck gazing out at the impressive mountains and wide waterway. "Truly beautiful," is how he later described the view in his memoirs. The lofty mountains inspired in him loftier thoughts, while the tall, thick forests reminded a companion of his home in Scotland. The dignified, ethereal scene so impressed this man of God that he even believed he heard a voice saying to him clearly, "This is where you shall serve."

"I most love to admire its awesome peaks, to look down into its broad and deep gorges, and sail on its turbulent sea," wrote Mackay in describing his emotional attachment to Taiwan. He devoted 30 years of his life to service on the island. Before his death he selected a burial spot on high ground overlooking the Tanshui River so that even after he had passed on he would have a view of his beloved green fields and the distant sea.

The mountains that moved Mackay to thank the Supreme Being are the Tatun Mountains of northern Taiwan. It is widely believed today that these are the peaks which inspired the Portuguese sailors to utter "Formosa."

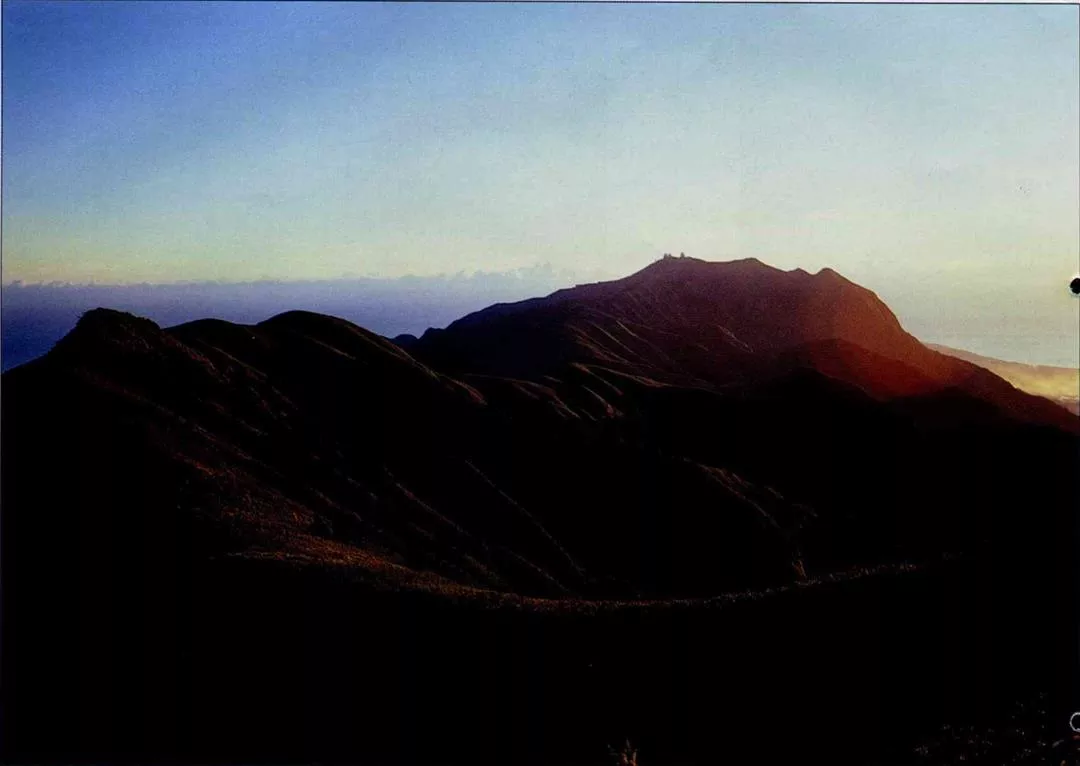

Geologically speaking, the Tatun mountain area includes the Tatun, Chihsing, Chutzu, and Hsiao Kuanyin chains. This mountain grouping was formed by volcanic eruptions between 2.8 million and 350,000 years ago. Although their highest point is only about 1000 meters above sea level, because of the dazzling array of them and the fact that the mountain folds overlook the sea, these mountains form the most impressive natural sight in northern Taiwan. They are visible across Taiwan's western plains all the way from the Lungtan exchange on the North-South freeway, which is in Taoyuan County. They are an even more pronounced landmark when viewed from the sea.

Liu Ko-hsiang points out that by the 16th century the kingdom of the Ryukyus (Okinawa), located between China and Japan, had long been sending tribute to the Chinese imperial court. When you look at the navigational lines, the frequent tribute and diplomatic journeys between Fujian and Naha (capital of the Ryukyus) must have gone right past Taiwan's northern coast.

The Tatun Mountains are Taiwan's only volcanic mountains; they have well-formed, symmetrical shapes. Many scholars believe that these provided the scenery which inspired Portuguese sailors to call Taiwan "Beautiful Island." (photo by Lin Tsung-sheng)

A Formosan mystery

Chen Kan, a 16th century Ming official, left behind the most famous Chinese writing on East Asian navigation after a trip to the Ryukyus and back. In it he recorded that, embarking on turbulent seas from Fujian, he followed the eastward route as had all Ming ambassadors for a century before him. On the second day, "we vaguely saw a small mountain in the distance; it was Little Ryukyu." In fact, it must have been northern Taiwan. The third day, they sped along, powered by a strong southerly wind, turning northward around the islands we now know as Pengchia (off Keelung) and Tiaoyutai. They reached the port of Naha in the Ryukyus on the 11th day.

"When the Portuguese came to Asia looking for Japan, which they thought of as the 'islands of gold,' due to considerations of safety they must have followed the existing Ming maritime routes. If this is indeed the case, they would have first seen the Tatun mountains, the most obvious landmark on Taiwan's northern coast," reasons Liu Ko-hsiang.

However, since Portuguese ships had already explored Southeast Asia by then, some people today argue that what they called Formosa was in fact the precipitous cliffs of eastern Taiwan, which they would have passed to their west as they sailed northward toward Japan. Or perhaps, it was the coral reefs and sea erosion around Kenting, on the Bashi Channel on the southern tip of Taiwan, that so astonished them. Still other historians argue that the Formosa that the Portuguese saw was the towering peaks of the Central Mountain Range, which they might have glimpsed while pushing their way north against the currents through the Taiwan Strait.

Although there is still no clear-cut answer available, it is still fun to pursue the mystery of "Formosa," for each side has its own logic. Those who place their bets on northern Taiwan say that Taiwan's west coast is flat and monotonous, with the sea often stuck in muddy tidepools. Moreover, sailors in the Taiwan Strait couldn't have seen much of the Central Mountain Range, since it is usually shrouded in fog. In any case, according to 16th century records, what they did see of it they thought to be a separate island in its own right, not Taiwan. So, runs their argument, "Formosa" couldn't have been western Taiwan.

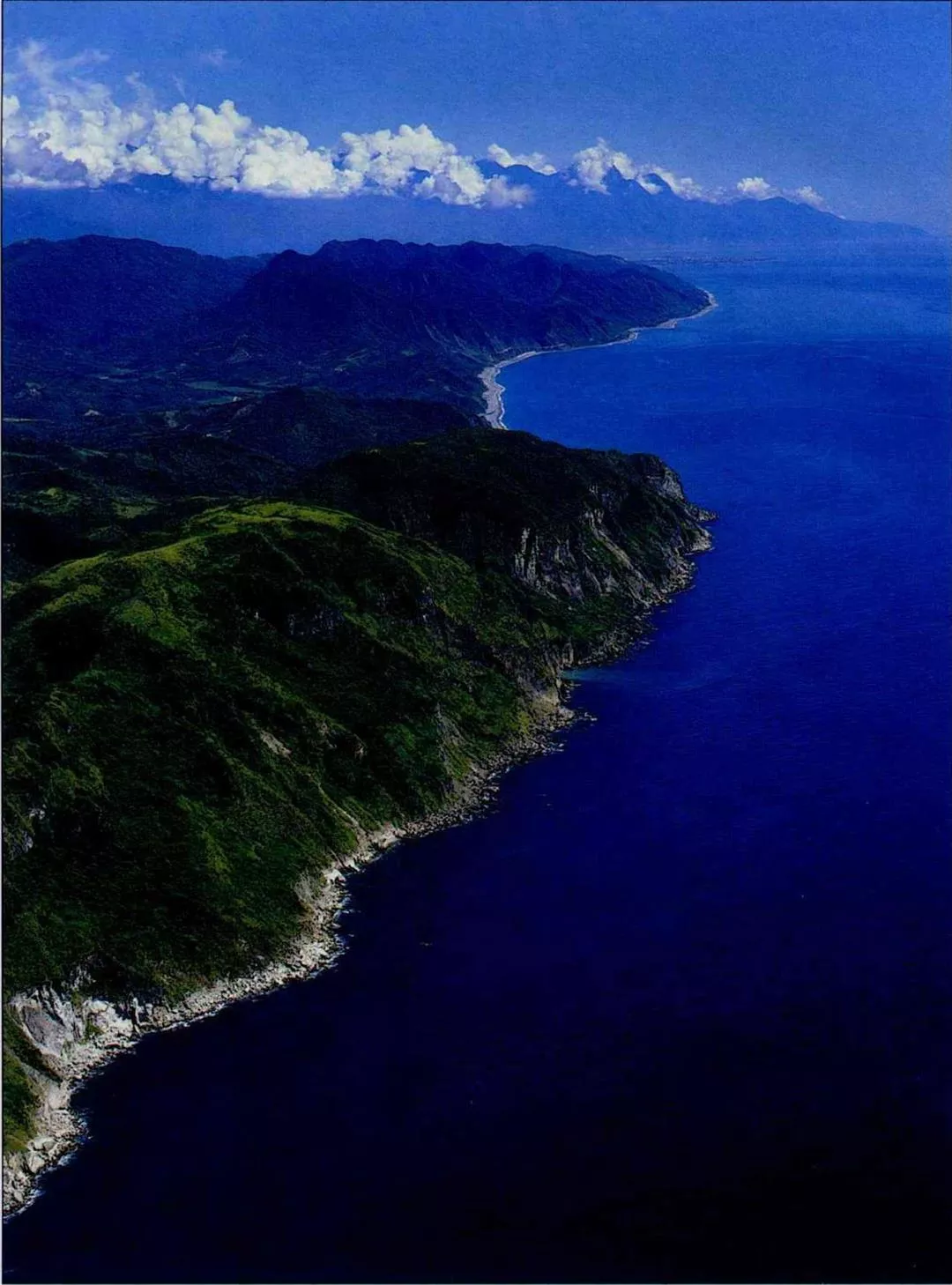

What about the east coast? A 19th century English naturalist, exploring the clear waters and sharp cliffs, recorded the stunning impression these imposing precipices by the sea made on him: "The Portuguese must have first seen this island from the north or the south, for if they had seen it from the east, they would not have chosen a word as mundane as 'beautiful' to describe it."

As for the southern tip of the island, its climate and environment are similar to the lands of Southeast Asia. However beautiful it may be, it is unlikely to have elicited gasps of delight from Portuguese mariners who had already seen all the beauties of Southeast Asia.

Chinese people set great store by geomancy. A place that "faces the sea with its back against mountains" is especially blessed. Such areas are often developed into cemeteries. Sadly, this frequently occurs with no concern for the impact of environmental damage on future generations. (photo by Vincent Chang)

In the eye of the beholder

So, it seems, the north coast still gets the most votes from members of the scholarly community.

"In early morning, before sunup, when the rays of the sun are just beginning to filter in, the Tatun mountain group is a majestic sight. The sunlight first flashes on the verdant topmost peaks like lanterns being lit. Then, like the opening of a stage curtain, the light unveils the mountains gradually, until the entire chain appears." This is how Huang Juei-hsiang excitedly describes the unforgettable impression the mountains made on him over two decades ago when he sailed into Keelung harbor after completing his military service in Matsu.

Liu Ko-hsiang served in the navy, and has done ecological survey work in the islets around Pengchia Island. Looked at from the ocean, he says, the volcanic mountains of the Tatun group appear to be perfectly rounded and smooth, presenting a markedly different picture from the craggy peaks of southern Taiwan. For Portuguese mariners who had already been through the Straits of Malacca and past Luzon Island it is Taiwan's northern scenery that must have seemed especially remarkable and fresh.

Although we have Ming era charts showing the sea route as passing along the northern coast of Taiwan past the Tatun Mountains and then turning left at the islands around Keelung to head up to Okinawa, it stands to reason that ships following this route would not have seen the northeast coast of Taiwan, which is to the east of Keelung. Yet the Belgian historian Vertente contended that it was precisely the blue peaks of the northeast coast that caused Portuguese sailors to sigh, "Formosa."

No matter whether you are talking about the Tatun Mountains or the tail end of the Huoshan and Hsuehshan Mountains toward Keelung, anyone looking from a ship at sea would not have seen some narrow, specific little point. Perhaps we will never be able to figure out which place it was that inspired "Formosa," but the most reasonable explanation still seems to be that ships were passing Taiwan's northern edge. This theory also says something about the unique aesthetic of this region's coastline.

"Look at the special features of European geography--the Alps, the Pyrenees... They are marked by jutting stone. And Portugal itself is a mishmash of forest and rocky slopes. The overall lush and verdant effect of Taiwan's northern coast would have been an unusual sight to Europeans," avers teaching assistant Chi Shih-ching of the Department of Geography at National Taiwan Normal University.

Looking at the other parts of the world on the same latitude as Taiwan, in Africa there is the Sahara desert, while in North America are the "badlands" around the US-Mexico border. But Taiwan's northern coast is covered with a range of vegetation. "You have to give the northeast seasonal winds the credit for that," says Huang Juei-hsiung.

Because the north and northeast coasts face directly into the seasonal northeasterly winds, the area is soaked in rain for the better part of the year, allowing vegetation to flourish. And of course 400 years ago this area was still completely undeveloped, so the primeval forest was intact.

Paradise lost

In fact, as far as many scholars are concerned, it doesn't really matter which part of Taiwan those Portuguese seamen saw first. "Today, what 'Formosa' should stand for is a good, clean environment," suggests Huang Juei-hsiang. The most important thing about tracking down the historical Formosa is to allow us to see what has changed over the past four centuries.

Today, when ships approach the mouth of the Tanshui River and pass the Tatun mountains, are their crews still moved to utter words of praise?

Look today at the mouth of the Tanshui, which long ago inspired Mackay to spend his life in Taiwan. These days apartment buildings crowd the slopes of the hills in the surrounding districts of Pali, Tanshui, and Kuantu, and about the only green spaces visible are decorative lawns in front of the houses.

And the Tatun mountains at which Mackay gazed in wonder from a distance have been through an even longer period of development, as Lu Li-chang, director of guide services at Yangmingshan National Park, explains: At the end of the 17th century, during the early years of the Qing dynasty, You Yonghe, a native of Zhejiang, started to gather sulfur here. At that time, the Tatun mountains were still covered with intact primeval forest, and the only residents were a few aborigines scattered next to rivers. Later, the Qianlong emperor (1736-1796), fearing that local bandits would use the sulfur to make gunpowder, ordered that the forests around the sulfur springs be burned away to deny the bandits any hiding places.

Next came waves of immigrants from the Quanzhou and Changzhou regions of Fujian, who undertook large-scale transformation of northern Taiwan. They cut irrigation ditches to tap the mountain rivers, cut down the trees for building materials, and engaged in slash-and-burn agriculture. In order to make furniture, they planted bamboo widely. In addition, they planted huge tracts of tea and daqing (used to make dyes) for export, leading to further deforestation. Settlers also transplanted acacia trees from Hengchun in southernmost Taiwan to cultivate for firewood. Thus the area's original low altitude vegetation was almost completely replaced, and the area of primeval forest rapidly declined.

In the 19th century, with the popularity of Indian and Ceylonese teas, and the invention of manmade dying agents, prices fell for local teas and daqing lost its market. Land that had been used for these two crops was left fallow, and was soon overgrown with wild grass. That is how the local residents came to call this stretch of peaks Tsaoshan, meaning "the Grass Mountains."

In the Japanese occupation area, in an effort to protect the water resources of the northern Taiwan area, the authorities restricted development in the Grass Mountains and promoted large-scale reforestation. The Grass Mountains rapidly became a forested area of "black pine" (Pinus thunbergii), "Ryukyu pine," Formosan sweet gum (Liquidumbar formosana Hance), and fir trees. And for the visit of the heir to the Japanese throne to Taiwan, the roads were lined with cherry trees.

Today, there are only a few small areas, within the jurisdiction of a national park, where one can see the primeval forest that was so "Formosa" to observers 400 years ago.

Fortunately, about ten years ago most of the Tatun mountain chain was included in the scope of the Yangmingshan National Park. With legislation passed to conserve the local environment, at least the current state of the area's ecology can be sustained, waiting for an opportunity to return it to its original condition.

The area of primeval forest in the Tatun Mountains was dramatically reduced by land clearance for the planting of cash crops. It was only after these crops lost their economic viability and the land was left fallow that the vanguard of vegetation--wild grass--could grow back. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

The changing sea

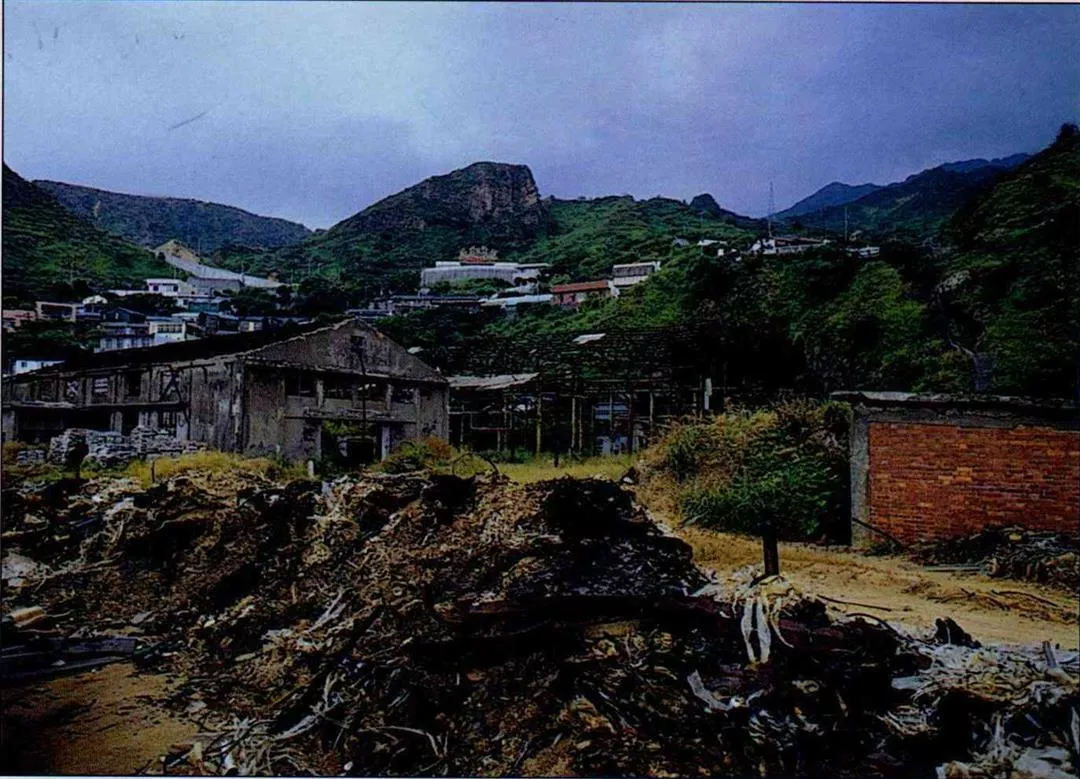

But the northeast coast, with its rock formations, cliffs, and eroded coastline, is not capable of recovering from manmade destruction as easily as are the Tatun Mountains. Abandoned mines, the "Yin Yang Sea," and the remnants of pisciculture ponds are all scars marking the changing scenery.

The tops of the mountains of Chinkuashih are scarred by one abandoned mine after another, each one surrounded by a patch of wilderness land. Meanwhile, down below the mountains, there is a body of water whose proper name is Lientung Bay. But, as the surface of the water is clouded with a yellowish mud, the local residents have taken to calling it "the Yin Yang Sea."

There had been rumors of the availability of coal in the Keelung region as early as the Dutch occupation period. But it was only in 1847, with the rediscovery of coal mines near Keelung by a Briton, that the area's mining production began to draw the attention of the imperial court and the international Community.

In the second half of the 19th century, coal was mined on a large scale around Keelung as part of the development program of governor Liu Mingchuan. Then coal miners found gold nuggets in the Keelung River valley, generating a wave of prospecting and mining. It is said that at the peak of the rush, the veins around Hsiaochinkua, Chiufen, and Chinkua-shih had attracted 100,000 prospectors.

Chinkuashih, from where you can look down upon Lientung Bay, was one of the three largest gold mines in the Keelung area in terms of both area covered and wealth yielded. Because Keelung has a rainy climate, water often seeped through the ground, emerging in the mines as copper mineral water. The Japanese channeled the water into deep pits or steel barrels to get it out of the mines, and the rust-colored water--contaminated with iron waste--was channeled into Lientung Bay. Because the sea currents in the area lack the strength to disperse the pollutants from the bay, heavy metals including iron, copper, and zinc have accumulated in the water. After retrocession, the Taiwan Metals Mining Corporation set up a copper smelting plant here, and explosives were used to dig up the minerals, causing the "Yin Yang Sea" to spread and become increasingly turgid and contaminated. Thirteen years ago, all work was stopped there thanks to the intervention of environmentalists, but the Yin Yang Sea is still finding it hard to recover.

The development of pisciculture by local residents has also damaged the land formations. When the coastal highway was opened to traffic in 1986, there was a sudden fad for abalone farming here. Excavators were driven right on to the northeastern coastline and dug a whole line of abalone ponds stretching across the sea-eroded flatlands. The Taipei County government, which at that time was in charge of the area, didn't even realize that people were putting up fish ponds in this largest stretch of sea-eroded flatland in all of Southeast Asia. When the authorities found out a year later, they adopted a firm attitude and banned the pisciculture, but the area has been left pocked with holes.

The exquisite scenery of the northeast coast has been pierced by a highway, abalone fish ponds, and recreational areas; there is little left of its former primeval scenery. (photo courtesy of the Northeast Coast National Scenic Area Administration)

Still Formosa?

Liu Ko-hsiang looks beyond the historical Formosa of northeast Taiwan to all of Taiwan. In the Dutch era there were hundreds of thousands of Formosan sika deer roaming the island; now this species only survives by being raised in captivity. The island's mountains were then covered with camphor trees; now the only examples left are ones planted next to city streets by man. And many of the bird species spotted by explorers in the 19th century are gone, never to return.... The whole environment of Formosa has changed, leaving nature reporter Liu to sigh with regret.

"Do we want to live in a place worthy of the name 'Beautiful Island'? Or will 'Greed Island' or 'Trash Island' replace 'Formosa' and become permanent synonyms for Taiwan?" wonders Huang Juei-hsiang.

Through a search for "Formosa," perhaps we can get to the question that requires even greater thought: How can we sustainably manage Formosa?

[Picture Caption]

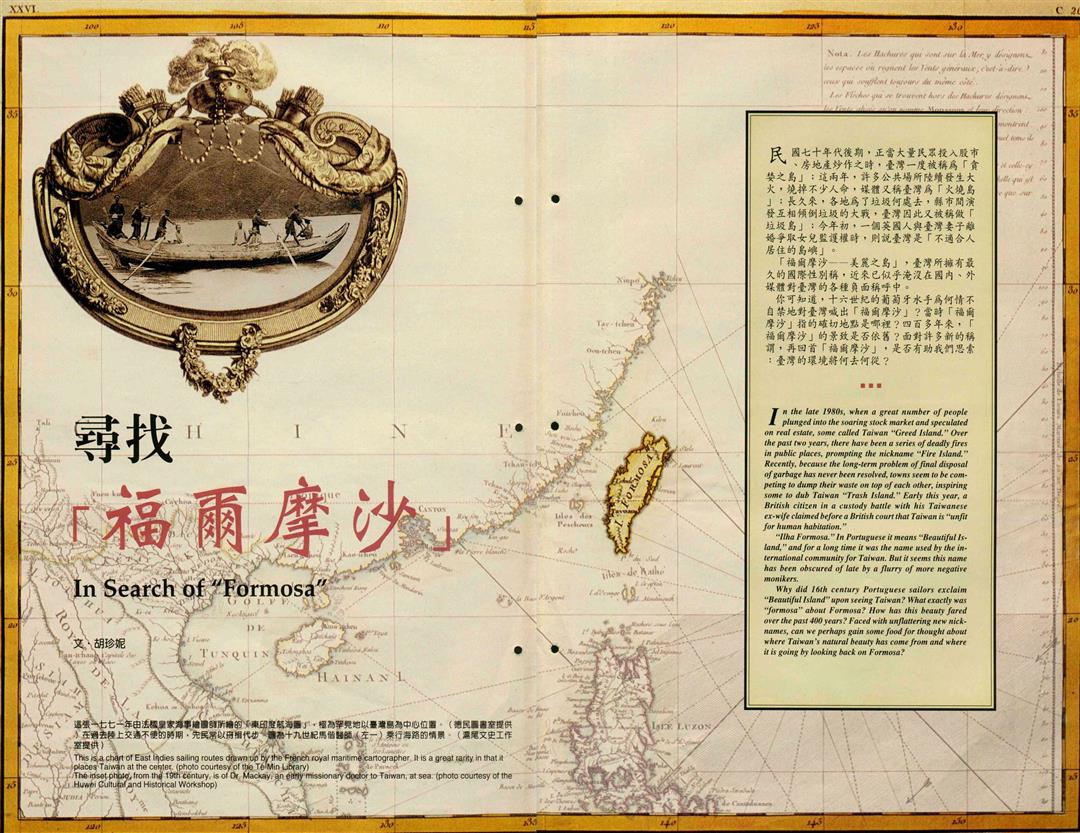

p.36

This is a chart of East Indies sailing routes drawn up by the French royal maritime cartographer. It is a great rarity in that it places Taiwan at the center. (photo courtesy of the Te Min Library) The inset photo, from the 19th century, is of Dr. Mackay, an early missionary doctor to Taiwan, at sea. (photo courtesy of the Huwei Cultural and Historical Workshop)

p.38

The topography of the northeast coast, shaped by sea erosion, is unique.(photo by Cheng Ying-sheng)

p.39

This 17th century Dutch book Verwaarloosde Formosa gives a detailed account of the Dutch withdrawal from Taiwan. The text remains important for studies of Taiwan's history. (photo courtesy of the Southern Materials Center)

p.40

The Tatun Mountains are Taiwan's only volcanic mountains; they have well-formed, symmetrical shapes. Many scholars believe that these provided the scenery which inspired Portuguese sailors to call Taiwan "Beautiful Island." (photo by Lin Tsung-sheng)

p.41

Chinese people set great store by geomancy. A place that "faces the sea with its back against mountains" is especially blessed. Such areas are often developed into cemeteries. Sadly, this frequently occurs with no concern for the impact of environmental damage on future generations. (photo by Vincent Chang)

p.42

The area of primeval forest in the Tatun Mountains was dramatically reduced by land clearance for the planting of cash crops. It was only after these crops lost their economic viability and the land was left fallow that the vanguard of vegetation--wild grass--could grow back. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.43

The exquisite scenery of the northeast coast has been pierced by a highway, abalone fish ponds, and recreational areas; there is little left of its former primeval scenery. (photo courtesy of the Northeast Coast National Scenic Area Administration)

p.43

In the past there was a great deal of mining in the Chinkuashih region. It brought wealth, but at a cost in environmental destruction. The photo is of the old smelting plant, which was shut down more than a decade ago, and is now in decay. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.44

Taiwan was called "Formosa" because of its beautiful verdant scenery. But with population growth and economic development, will it still continue to hold this nickname in th e future? (photo by Chen Min-min)

In the past there was a great deal of mining in the Chinkuashih region. It brought wealth, but at a cost in environmental destruction. The photo is of the old smelting plant, which was shut down more than a decade ago, and is now in decay. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Taiwan was called "Formosa" because of its beautiful verdant scenery. But with population growth and economic development, will it still continue to hold this nickname in th e future? (photo by Chen Min-min)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)