Almost no one in Taiwan is unfamiliar with the illustrious Linwang the Elephant, who resides at the Taipei Zoo, located in the suburb of Mucha. He is the old "grandpa" that many kids specifically ask to see when they visit the zoo. When surveys have been taken of the most popular animal, Linwang always sits unbudgeable in first place.

The principal cause of Linwang's renown is that he is the zoo's oldest occupant. But few people know that in the past, he trudged, step by step, in the company of Chinese soldiers who had been stationed in India, as they marched in World War II.

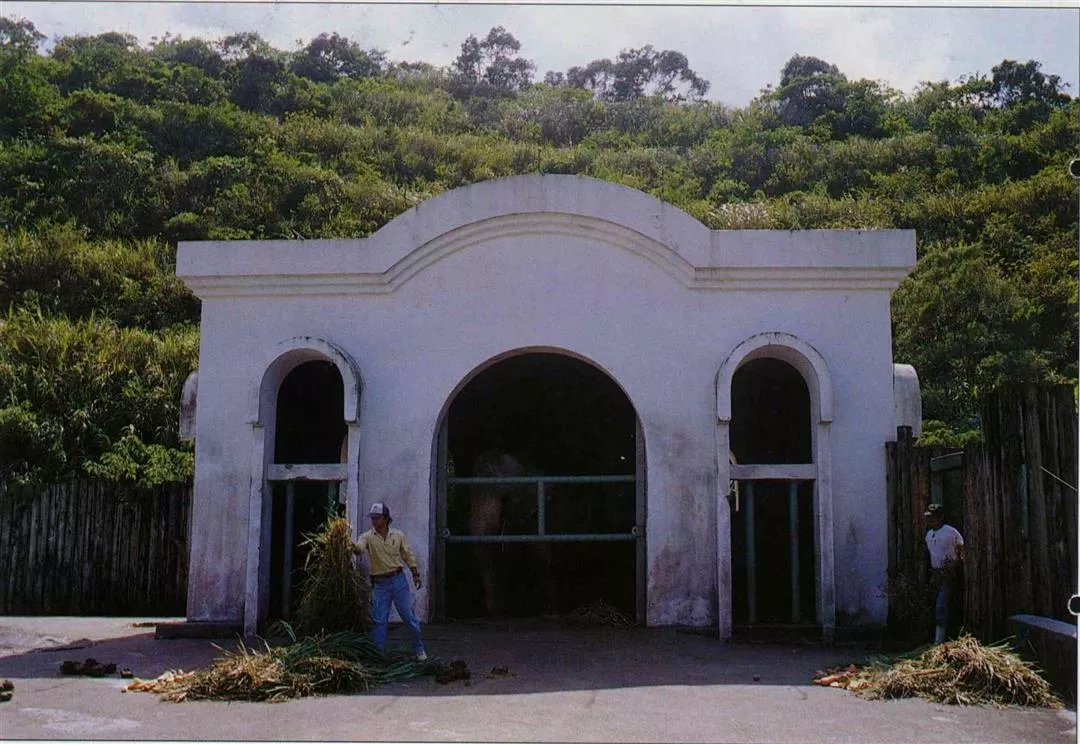

In the last few months, Linwang and his wife Malan have been taking a long vacation, because their home, the zoo's "Asia and the Americas" section, is currently being expanded. Normally, when it's time to "go to work," they walk to the viewing area from their living quarters, the "White House," and they face pair after pair of visitors' eyes, wide with curiosity. Now all they look out upon is rolling mud.

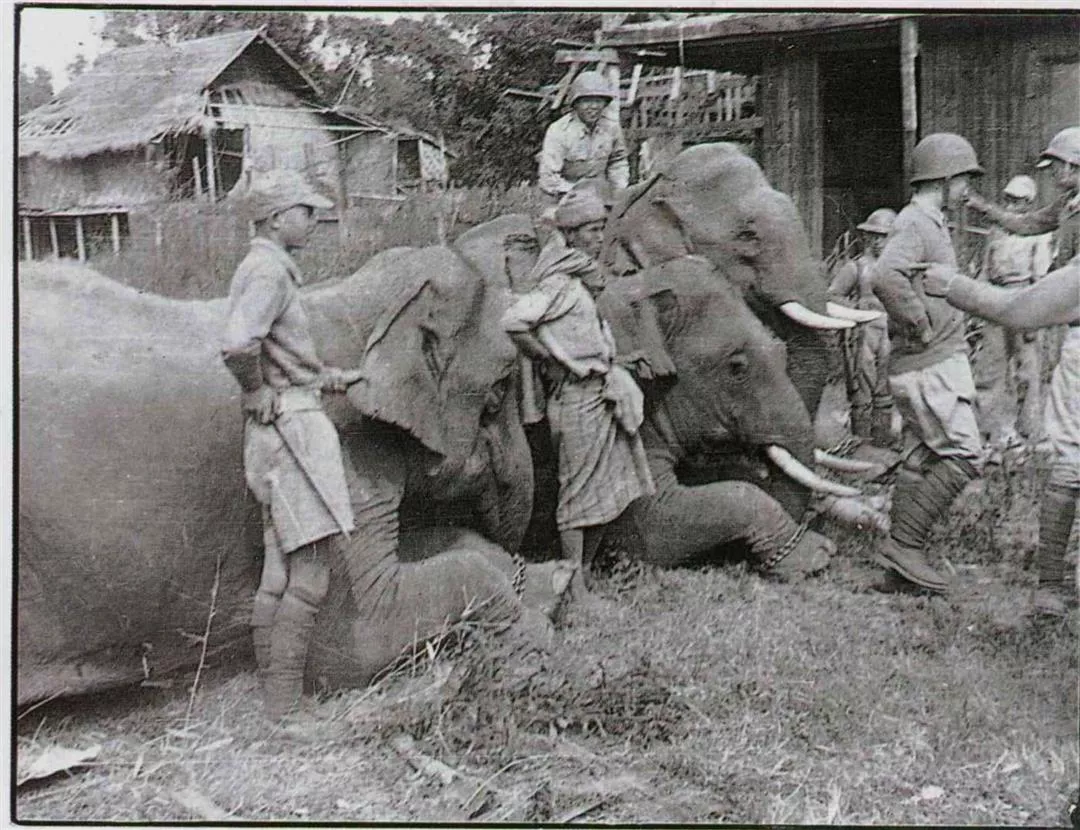

The elephant transport team, acquired by the army in the Burmese theater during World War Ⅱ. (photo courtesy of Luo Chao-chun)

The peculiar combatant

At two in the afternoon, the keeper brings the couple their lunch--bundled-up Chinese pennisetum reeds as an entree, and side orders of carrots, bread and corn. Linwang is already blocking up the left side of the White House where the feeding station is located. Malan, whose body is a size smaller than her hubby's, has no way to take up the number one position and can only find an emptal niche from which to stretch out her long trunk and let out a greeting in the direction of the food, expressing her delight at its arrival.

It is quite a sight when Linwang curls and swings his trunk, promptly grabbing a mouthful of reeds. First he makes a couple of motions in the air, shaking off the mud and dust, and while he's at it scratching an itchy spot for a moment. Then he drops the reeds under his enormous foot, breaking off the thicker stems with a snap. Only then does he stick them in his mouth with satisfaction. Afterwards, he'll complement them with a few carrots. Mixing his main course with side dishes, he delightedly munches.

Sometimes, when he has not yet swallowed the food in his mouth, the next batch has already been made ready, and loathe to tire himself out holding it, he simply wedges it between trunk and tusk. When he's ready, he just lightly uses the tip of his trunk like a finger to firmly pluck up the grass without dropping a single strand. This was a movement he often used when he was young, moving logs in Burma.

A bulldozer thunderously bears its fangs and scuffs its paws in front of Linwang, but he is already used to it, and hardly even moves. This, however, is only a recent turn of events. Wen Yung-chang, curator of the Taipei zoo's collection department, says that in the past whenever Linwang heard any loud mechanical noise, he would become a nervous wreck. When construction had just begun, one could frequently witness Linwang blocking up the ditch, waving his trunk in protest at the two excavators.

Or perhaps, with his keen memory, was a recollection floating to the surface of his mind, of a battlefield deep in the tropical virgin forest, permeated by gunsmoke, stray bullets flying in all directions?

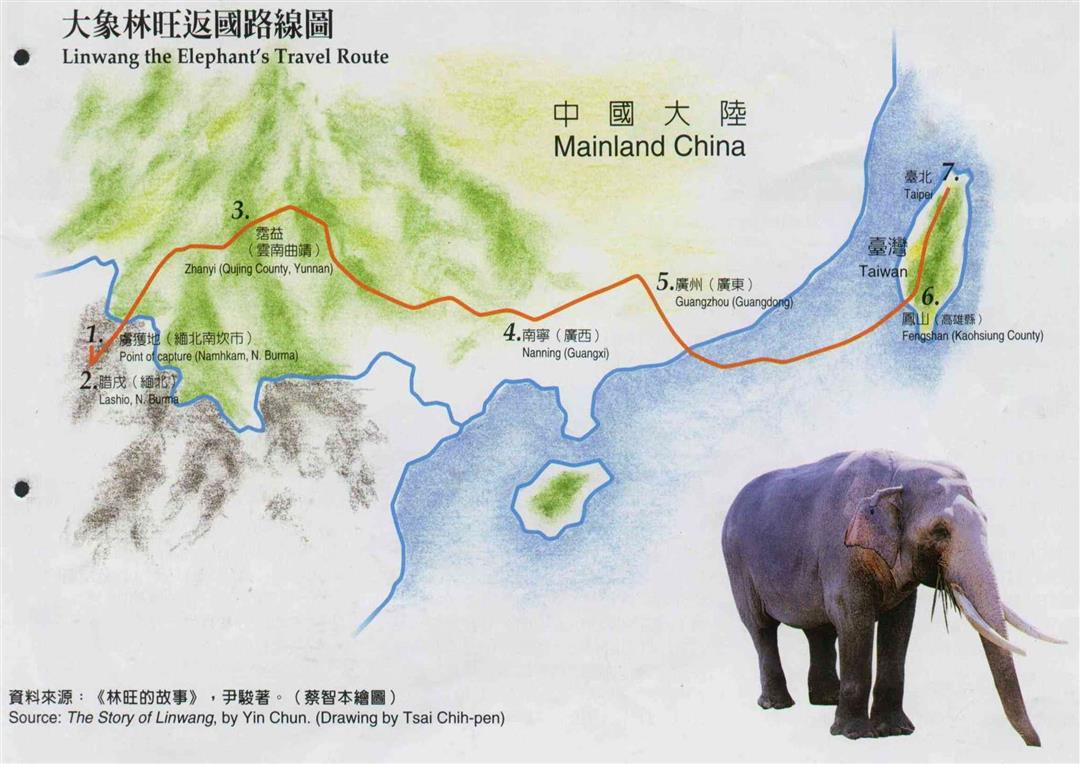

Linwang the Elephant's Travel Route Source: The Story of Linwang, by Yin Chun. (Drawing by Tsai Chih-pen)

China soldiers goodbye

At first Linwang had a Burmese name which meant "King of the Jungle." Later on, the media picked up on the Chinese name Linwang (林 王), which has the same meaning, and later the character for "Wang" was slightly modified (林 旺). This male Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) was born in Burma, sometime around 1918. Throughout Burma, the local people have the custom of catching and taming wild elephants, turning them into beasts of burden, "living machines" that move lumber. Originally Linwang was one of these, but in 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when World War II spread to Southeast Asia, Linwang found himself conscripted as "porter." But the armed force which drafted him was not the Allies, but the Japanese.

At the time the Japanese had occupied Indochina and were advancing northward along the Burma Road, planning to sever transport of military supplies into China. For this purpose, they commandeered elephants they found along the way to carry guns, provisions and ammunition. China organized three corps of more than 100,000 troops comprising the "China Expeditionary Force," assisting the British forces of the Burmese colonial government in combat, in what became the first major hostilities in the Burmese theater. Later on, the British forces suffered heavy losses and retreated into India. The Chinese forces, who were responsible for covering the retreat, made their way, under the leadership of the late General Sun Li-jen, through savage and undeveloped western Burma, rendezvousing in India.

After a period of retraining, the Chinese troops which had made their way to Ranchi in India were renamed the "Chinese India Corps." Of these, the New Number One Corps received orders in 1943 to retrace their steps in a counter-attack as part of the second phase of warfare in the Burmese theater. Retired serviceman Yin Chun relates that the Number One Corps won battle after battle, and the Japanese gradually retreated. All that was left were the words "China soldiers goodbye," carved into a tree.

Thereafter, when the Number One Corps' Thirtieth Division was ordered to occupy Namhkam, they encountered a predicament. The Ruili River, 100 to 200 meters wide and two to three meters deep, cut across their path. If they were to cross the river by boat, they would easily become the targets of enemy fire. Coincidentally, the troops captured a Japanese prisoner, and it was the reconnaissance team staff officer Yin Chun's responsibility to interrogate him. He revealed that it was possible to use elephants to act as the pillars of a temporary bridge. After reporting to his superiors, Yin Chun led a five-man squad, crossing the river in search of elephants.

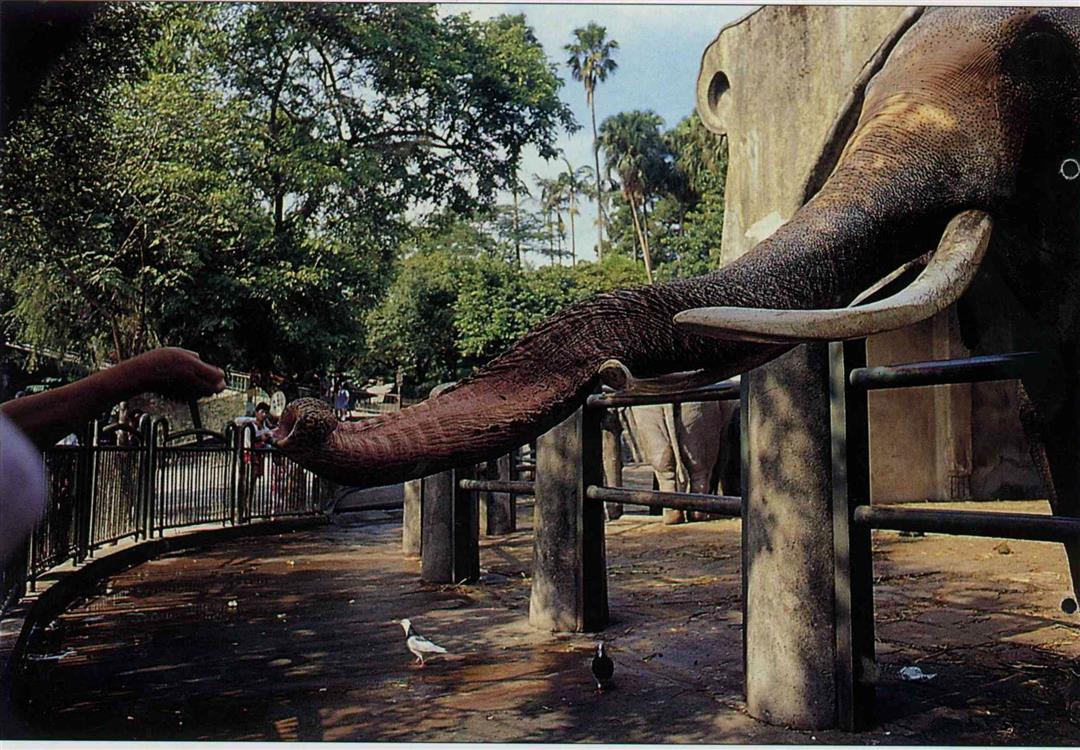

Linwang's nimble proboscis, with which he nips snacks from visitors' hands, is the very same "hand" with which he labored in the jungles duringthe war. (photo by Fu Chun)

Trapping tuskers

"At that time, we encountered heavy rain, which kept up for several days. The width of the river suddenly increased to more than 400 meters. Finally, we got to the other side. We pulled out Burmese garments to disguise ourselves. We wandered around in the forests for some time, and then finally in a bamboo grove at the foot of a mountain we discovered a group of enormous black shapes. When we saw them--why, they were the elephants we were looking for! There was still rice tied to their backs, and there were several Burmese elephant drivers tending them.

"An intelligence officer who could speak Burmese pretended to be passing down orders from the Japanese military, and told them to march forward. We walked and walked, then the elephant drivers figured out that we were heading in the wrong direction, and refused to go any further. At that time, we had no choice but to pull out our guns and announce our identity. Then the frightened elephant drivers scattered in a big flurry, leaving behind thirteen elephants, big and small, male and female. Linwang was the youngest and strongest of them.

"But because the water's current was simply too swift, even the elephants couldn't stand their ground in it. So we used an old method. Everyone lashed together bamboo rafts, and we used them to pull two thick ropes to the other side. Then we clambered across. In an afternoon, we retook Namhkam. Three days later we held a press conference on the battle site. Those thirteen elephants instantly became the focus of media attention. Their picture even got circulated all over the world."

From then on, Linwang and his chums stayed in the trucking business, becoming the elephant transport team, carrying munitions and food supplies along with the original mule team. And they became a source of amusement for the troops.

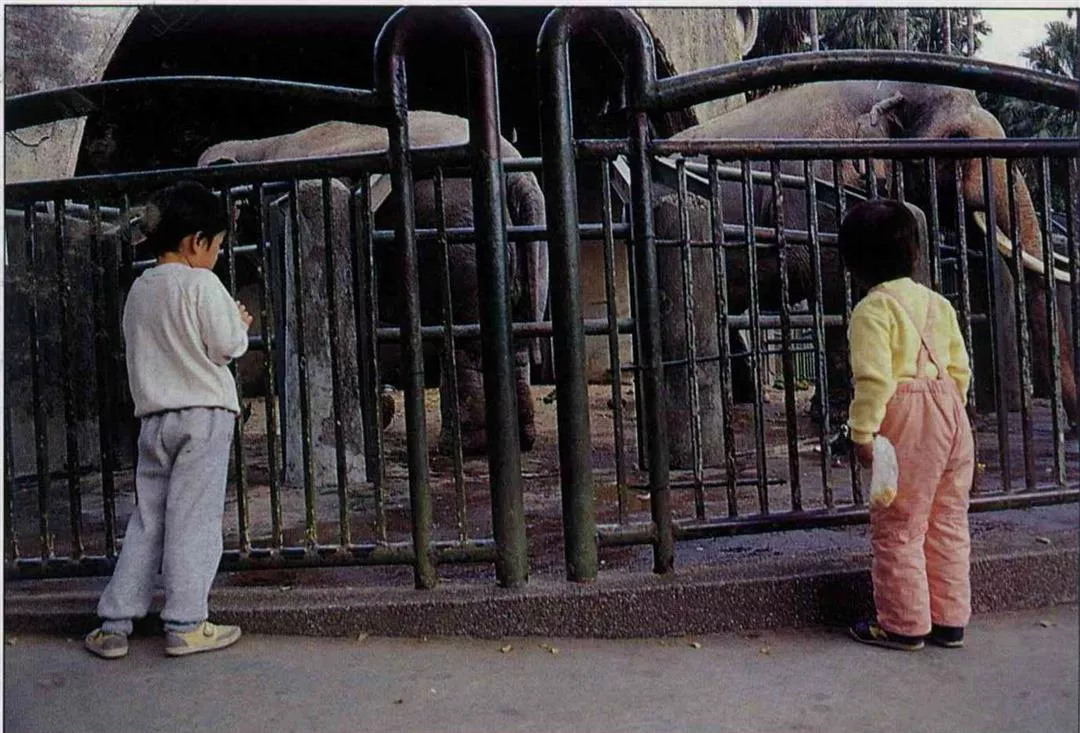

Linwang is the old "grandpa" that many kids specifically ask to see when they visit the zoo. Malan his wife is on the left. (photo by Fu Chun)

Splish splash

In his book The Story of Linwang, Yin Chun writes that all the elephants "would wrap their trunks around crate after crate of ammunition and carry them onto the big cargo trucks. Sometimes they would also help us rescue trucks that were bogged down deep in the mud. They had tremendous strength and worked fast. They were really good helpers, useful in a lot of different ways."

According to the recollection of retired soldier Lan Wei-chiang, who enlisted in the intelligence service at the age of 17, Linwang was a playful friend. Lan didn't directly take care of the elephant team, but he was good friends with the soldiers who did. They added a lot of fun to the tough military life.

"Linwang loved water. As soon as the team took a break, he would jump into the water, taking a bath along with us, who were all soaked with sweat. He would suck up water with his trunk and then spray us, and we would use a water basin to splash him back. Quite often, I'd also feed him, filling up my metal teacup with rice, corn or whatever. His trunk was like a vacuum cleaner. In an instant he'd snuffle it up and eat everything."

In April of 1945, the Chinese India Corps was ordered to return to China. The mule and elephant teams were not able to fly in airplanes, so they had no choice but to advance step by step along the Burma Road. Along the way from Lashio in Burma to Qujing County in Yunnan Province, they were escorted by Yin Chun, as well as two elephant trainers. In the second half of the journey, responsibility was handed over to military intelligence platoon leader Shang Hsueh-ching.

The many different events that occurred during this period of time have still remained fresh in Yin Chun's mind. At first, within the borders of Burma, everything was more or less smooth, but once inside China, the elephants started to show signs of not adjusting properly.

Together Linwang and Malan eat 500 to 600 kilograms of feed a day. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

It's a long read home

The weather tended to be hot and dry, and the road went from being asphalt or grass to an uneven stone surface, strewn with pot-holes. As they rushed their journey both day and night, the elephants' feet quickly blistered and tore, even becoming infected and festering. When they saw this, the soldiers felt great pity for them and took off their uniforms to bind the elephants' feet. In two-man teams, they supported the elephants, silently marching forward. Once they came upon some water, the elephants would frequently grow lethargic and refuse to get up. Only when the soldiers bound the back of the elephants' legs with thick ropes or burned their bums with fire, could they force them to stand up again.

At the same time, because the elephant team did not belong to the formal military organization, they were not apportioned feed, so besides sharing the mules' feed with them, the soldiers had to exchange things for money along the way or straightforwardly "solicit donations" in order to raise funds to feed them. But due to cumulative fatigue and malnutrition, in less than two weeks, six elephants collapsed from exhaustion. And all one had to do was look at the ones who remained, as their gait became increasingly wobbly, to know that they were sick. The story goes that Linwang suffered from night blindness, and the troops used a traditional method of treatment: They stuffed opium in a pear and fed it to him, then he was cured.

When Yin Chun saw the first signs of something wrong, he hurriedly requested his superiors to change the mode of transport to trucks. In that way, they safely sent the remaining seven elephants to the military camp in Zhanyi, Qujing County. There he handed them over to Shang Hsueh-ching, and after they were nursed back to health, they continued on. The original elephant trainers had taught the pachyderms a few simple movements, such as carrying things on their heads, raising their front hooves and lying down. After the soldiers had mastered the verbal commands, these small skills unexpectedly became their tools for making a living.

Elephants really love water. Although it's only a little muddy pool, Linwang looks like he's discovered something precious. (photo by Cheng Chih-wen)

Traveling circus

At the time, many villagers had never seen an elephant. So in order to preserve the sense of novelty, every time they arrived at a different village, the soldiers would enter the town at night, choosing to put up camp somewhere with an open square, such as a school or temple. The next day they would bang gongs and beat drums, calling everyone from all over to come see these living "spoils of war" perform. If the audience was impressed with the show, they could pitch in a little to feed them, giving the procession a bit of the flavor of a traveling circus.

The seven elephants and their handlers spent about half a year in this way, until they finally reached their intended destination, Guangzhou. At that time they were settled in a big courtyard near the Pearl River Bridge, where the city's residents could view them. The proceeds were donated for famine relief in Hunan.

In order to spread the fame of the Chinese India Corps' military exploits all over the land, Sun Li-jen subsequently chose four elephants to be sent individually to zoos in Peking, Nanjing, Shanghai and Changsha. That only left the male elephant Linwang and two females, Ah-Pei and Ah-Lan, who were kept at the Guangzhou Park. Nevertheless, they weren't allowed much time to rest. When the Army Number One India-Burma Corps Memorial Military Cemetery was being constructed, the three elephants were once again recruited to carry building supplies.

In 1947, Sun Li-jen was ordered to go to Taiwan to train new soldiers, and the three elephants were also hoisted up in huge nets aboard a ship (the Haiji), in which they made their imposing way across the sea to Fengshan in Kaohsiung County. The Echo Children's Encyclopedia contains an article introducing Linwang, which quotes an old soldier, Chou Ho-ting, who at the time took care of the elephants aboard ship. He said that Linwang tended to get seasick, but if he had eaten to his content, he was quite well behaved.

Nevertheless, the amount of feed had not been properly planned out, and a good part of it was blown overboard by the wind, so the three elephants, tied down to the deck of the ship, became so hungry that they even ate the canvas that was used to block the rain. For five days, they jostled around on the high seas. They could not walk at all, and they must have been miserable.

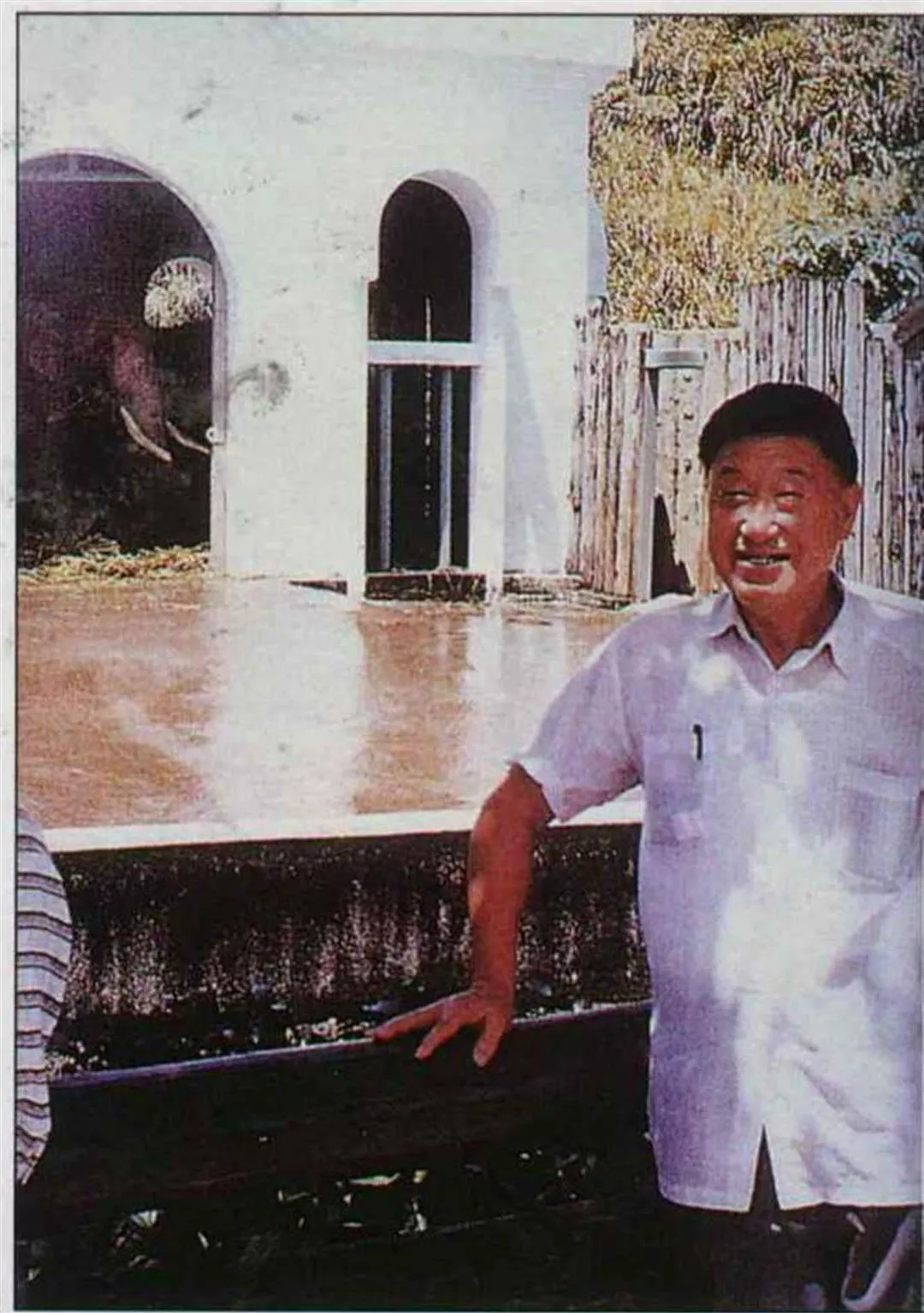

The retired soldier Yin Chun, who seized Linwang away from the Japanese army, still returns to the zoo to gaze at his old war buddy. (photo courtesy of Yin Chun)

The elephant veteran

When they arrived at the military base at the head of Fengshan Bay, Ah-Lan passed away, perhaps because she could not adjust to the new environs. And because the military was not actively engaged, the remaining two elephants could only look forward to retirement. Later on, they were sent straight up to the Taipei Zoo, then located in the northern suburb of Yuanshan. In 1954, Linwang and Ah-Pei were formally discharged from military service.

Not long after, Ah-Pei also breathed her last, and her remains were sent to the provincial museum as a specimen. Linwang could no longer see his last remaining companion, with whom he had struggled through thick and thin. He became the one-and-only surviving elephant "veteran."

Every year, male Indian elephants go through two musts, when their temperaments become irascible and restless. For this reason, most zoos do not favor raising them. Linwang, however, was the only surviving elephant to have served in the Burmese theater during World WarII, and the nation wanted to spare no efforts in caring for him. When he was around 35 years old, the zoo administration decided to marry him off to a lovely young lass named Malan.

On the other hand, "marry" might not be the most appropriate term. Malan, who had arrived at the zoo two years before Linwang, was only three years old when they paired up. "Old Master" Chen Teh-ho, collection department specialist at the Taipei Zoo, taught her to perform since she was little. He recalls that at the time, Malan stood only one meter tall. Often in the evening, when no one was watching, she would jump at the chance to lie on her side and push her way through the railings. Then she would roam all over the zoo grounds in the night. The difference in age makes the domestic scene between the two very tranquil. But from the viewpoint of human beings, it might be fitting for Linwang, thirty years her senior, to be her father instead of her husband.

After Linwang arrived, whenever it was time to practice performing, Malan would hide behind Linwang, shirking her duties. Finally, they simply gave up training them. Since they feel so good about each other, their love ought to have quickly produced issue, but reality is far from what we would like to believe. Chen Teh-ho says that because of the difference in ages, they are constantly playing a game of "hide-and-go-seek."

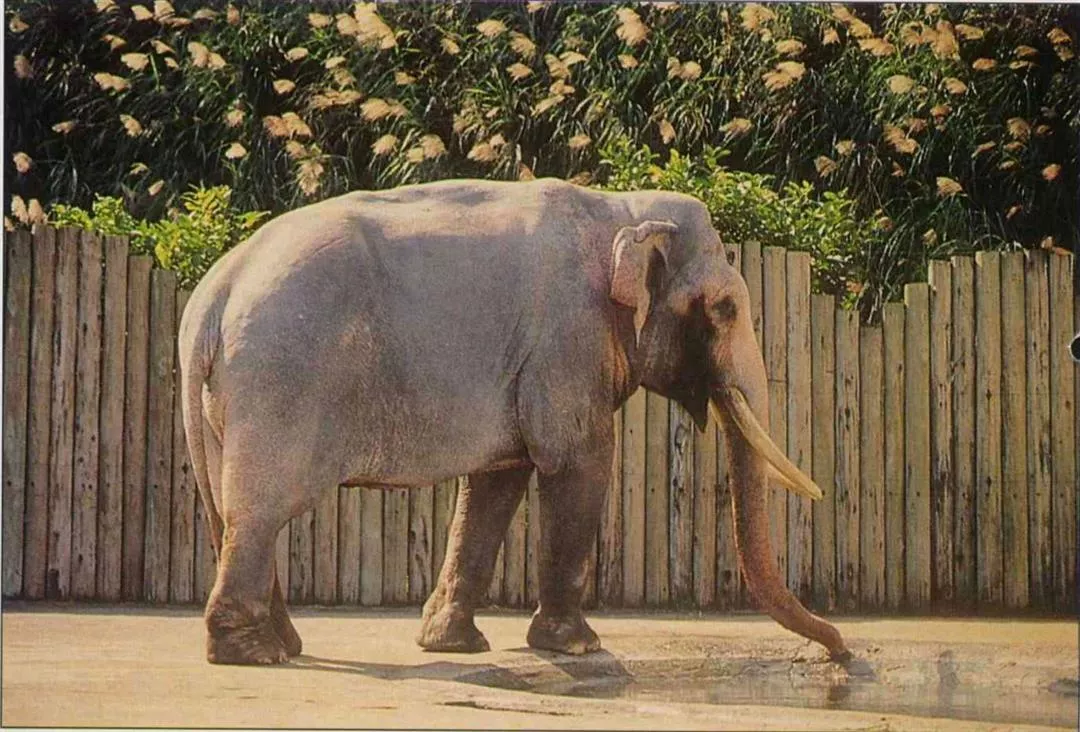

The bride and groom grow old together. Elderly Linwang, who spent his youth assisting young Chinese soldiers in World War Ⅱ, peacefully enjoys his waning yea rs in the zoo. He is the one on the right with tusks. (photo by Cheng Chih-wen)

The old gent and his child bride

When Linwang was rutting, Malan was still too young. More than a decade later, when Malan had grown up, Linwang had no keen interest in being intimate. For this reason, one can often see Malan snuggling up to Linwang's side, but he rudely drives her away with his tusks. Linwang can certainly not evade responsibility for the many wounds on Malan's body.

Wen Yung-chang relates that one morning a keeper came to feed them, but to his surprise, Malan was nowhere to be found. It turned out that Linwang had pushed her into the moat. Chen Teh-ho and a member of hardy fellows had to poke Malan's buttocks with a bamboo pole to coerce her to lumber out.

On an ordinary day, however, the couple live very much at peace. They pass their time wandering about the compound, sleeping, bathing, and enjoying breakfast and dinner, which they receive at set times every day. The memories of war have already faded in the distance. But when he was more than fifty years old, Linwang was diagnosed as having a tumor of the rectum, and his personality made a 180°turn.

Chen Teh-ho explains that twenty years ago, techniques to treat this kind of disease were still very backward. The zoo used a "rough-shod" approach. They hobbled Linwang's feet and tied every part of his body with rope. Then they directly pierced the afflicted area with tools, performing electrotherapy and applying medicine. Linwang was tormented in this way for several hours, and eventually he was cured. But with his remarkably acute memory, he virtually came to equate zoo workers with pain. Therefore, the only people he lets approach him are keeper Wang Wan-chun, who fed him for over forty years and only retired two years ago, and a few other folks with whom he is very familiar. And "Old Master" Chen Teh-ho, who led him along the distant journey from Fengshan to Yuanshan, describes their relationship as: "I know he can't stand me, but he also fears me, so he doesn't dare to be reckless."

Bearing witness to history

That "well-behaved" Linwang the Elephant, who would happily perform tricks on command, is now basically nowhere to be seen. There are even unconfirmed reports that he slaps his wife with his trunk to let off steam.

Looking back over more than forty years of memories, the old soldiers who were his friends during the war seem to be filled with sorrow. At a veteran's reunion, one old soldier from the Number One Corps remarked with quite a lot of sympathy, "His old buddies that fought by his side have all died. His wife is so much younger than him, and he has no children. You tell me, how could he not be lonely?"

During Linwang's big 66th birthday celebration, Lan Wei-chiang especially brought his metal teacup, rushing from Tungshih, Taichung County to see his pachyderm pal again. He filled the cup with popcorn, and standing in front of the railing, lifted it up high. Linwang quickly walked forward, and twisting his trunk, transported the popcorn into his mouth. "When I saw that his head was all shiny and bald, and he moved so slowly, and he was covered with age spots, I felt so sad. Ah! He's old, he's all used up."

Recently a group of old friends from the Number One Corps who still keep in touch have been cooking up the idea of returning to Guangzhou and rebuilding the Number One Corps memorial, which was demolished during the Cultural Revolution. In their minds, it was a reminder of China's glorious military contribution to a foreign campaign. "I've heard that elephants can live to be a hundred. Maybe the last surviving member of the Number One Corps will be Linwang," one old veteran muttered to himself.

Without a doubt, Linwang's comrades-in-arms either perished on the battlefields of yesterday, their remains deserted and covered with weeds, their names long forgotten, or they have gradually withered with the passing of years. But at this time when we pay heed to the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World WarII, taciturn Linwang tenaciously stands as a clear-sighted witness.

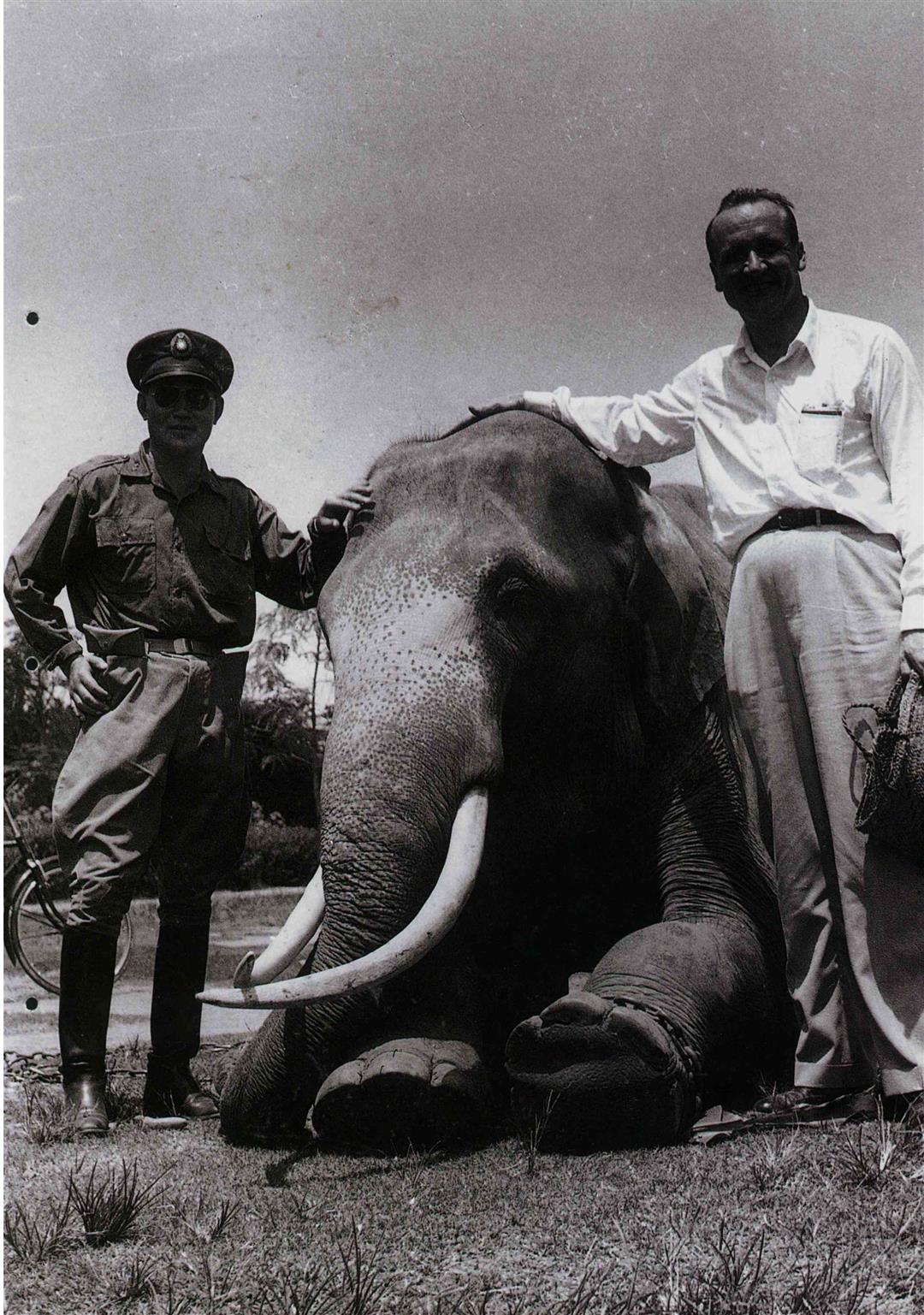

[Picture Caption]

p.109

Linwang was a proud "comrade-in-arms" of the late General Sun Li-jen. On the left, Commander-in-Chief Sun Li-jen. On the right, "friend of China" US Senator Knowland, both pictured with Linwang at Fengshan. (photo courtesy of Luo Chao-chun)

p.110

The elephant transport team, acquired by the army in the Burmese theater during World War II. (photo courtesy of Luo Chao-chun)

p.111

Linwang the Elephant's Travel Route

Source: The Story of Linwang, by Yin Chun. (Drawing by Tsai Chih-pen)

p.112

Linwang's nimble proboscis, with which he nips snacks from visitors' hands, is the very same "hand" with which he labored in the jungles duringthe war. (photo by Fu Chun)

p.113

Linwang is the old "grandpa" that many kids specifically ask to see when they visit the zoo. Malan his wife is on the left. (photo by Fu Chun)

p.114

Together Linwang and Malan eat 500 to 600 kilograms of feed a day. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

p.114

Elephants really love water. Although it's only a little muddy pool, Linwang looks like he's discovered something precious. (photo by Cheng Chih-wen)

p.115

The retired soldier Yin Chun, who seized Linwang away from the Japanese army, still returns to the zoo to gaze at his old war buddy. (photo courtesy of Yin Chun)

P.116

The bride and groom grow old together. Elderly Linwang, who spent his youth assisting young Chinese soldiers in World War II, peacefully enjoys his waning yea rs in the zoo. He is the one on the right with tusks. (photo by Cheng Chih-wen)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)