Arriving in the Yuli township of Hualien county, you might come to the conclusion that people are playing a joke on God. Observing the Chingshui (which means clear water) and Lele (which is a Mandarin transcription of word that means murky in Taiwanese), one can't help but think that the names should be swapped.

But it's not that our forefathers misunderstood Mother Nature's will but rather that the disrespect shown by recent generations for their natural inheritance has taken its toll.

The two rivers run parallel from the Central Mountain Range east, flowing out of the mountains and into the valleys, past lush forests and rocks, until they meet in Yuli of Hualien, where they empty into the Hsiukuluan River.

Because of the differences between the mountain areas from which they start, these two principal tributaries of the Hsiukuluan have dissimilar appearances and different destinies.

Proclaiming the Eternity of Nature: The main source of water for the Chingshui, the southern of the two, is the Chingshui Valley, which is 700 meters above sea level in the Central Mountain Range. The geology there is formed of interlocking sandstone and serpentine. The river bed was petrologically stable. The river was originally strewn with large green chunks of serpentine, and the water was transparent green, clear in spite of the erosion brought on by the violent rains of the typhoons, which hit the area straight on every year.

To the north, the Lele River draws its water from such peaks as Mt. Hsiukuluan, which at 3,800 meters above sea level is the highest peak of the Central range, as well as Mt. Tashuiku and Mt. Tafenchien. The main branch of this white water river runs for a course of 53 kilometers. Upstream it has almost 10 tributaries. It flows between steep mountains, and its two banks are primarily made up of easily collapsing sandstone and shale. Hence its waters are good for crops and rich with minerals. Even on clear days it is still a bit cloudy, and thus the Taiwanese downstream called it "the murky river."

But the natural color of the Lele River did not detract from its great beauty. The two rivers flowed between the grandiose mountains with a steady flow of water and abundant water resources as if to announce the eternity of nature. . . .

The Chingshui River--Past and Present: The Chingshui River began to change first.

"When I was small, I'd have to take a winding path between the mountains and climb over huge boulders to come to play in the Chingshui," recalls fifty-something Lien Chen-te. In 1970 the river downstream had a depth of half a man's height, and from time to time you could catch eels weighing more than 13 pounds.

Hsu Kai-jung, 70, remembers that during the period of the Japanese occupation, the Japanese would come every year to worship at their Shinto shrines. They'd order aboriginal youths to pick trifoliate jewelvine, which would be ground up and dumped in the river. Poisoned zacco and other fish could be seen from the upper stretches of the Chingshui to the mouth of the Hsiukuluan.

Teeming with life, the river also had a remarkably active course--which has changed from being bounded by steep U-shaped canyons to having a wide and shallow river bed. Ordinarily this process occurs over the course of thousands of years and cannot be observed in a human lifetime. But the Chingshui has had a new incarnation in only two decades.

From Yuli upstream, "the river channel today is twice as wide as it was 15 years ago," says Lin Wu-lang, who works for the Yuli Work Station of the Forestry Bureau, while sitting in a jeep that seems almost to be jumping as it bumps along the Chingshui's river bed. Wherever one turn is are small and large chunks of rock being continually pushed down stream. When piles of them block the way, the water spills in all directions, washing away the river banks. Hence, the earth and rocks, after becoming loosened, are continuously collapsing.

A Murky River? A Dry River? Now the rainy season is bringing rock and sand rumbling down like the cavalry, and the downstream stretches of the Chingshui are full of sand and mud, making the river hundreds of times more turbid than the Lele, a naturally "murky river." In Changliang borough of Yuli township, there are over 146,000 square yards of rice paddies irrigated with river water from where the Chingshui and Lele meet. Because of the sand and mud in the Chingshui, two irrigation water inlets have been buried under the bed of the river. "Only one is left, and the dredger has to be there at all times, ready to clear it of mud," says Chang Chih-chao of the Yuli Work Station of the Hualien Irrigation Association. In six or seven years, some NT$20 million has been spent on dredging fees.

Today the river will be dry for a period only to flood shortly thereafter. If there's rain, the water will arrive so fast that the banks will suddenly overflow. The Chingshui dike, on the right bank of the lower Chingshui, has been cut up by floods three years running. But the river dries up after a few days without rain, and during the dry season, even a small trickle of a stream is too much to ask for. The Chingshui river dries up at times like this and the catching of fish and shrimp has become a lost art along its banks. "The river is already hydrologically dead--there's simply no way to stop it," says Chang Chih-chao. "We should have given up long ago."

While the Chingshui has gone from being a small clear stream to being a "raging river," the Lele River has taken the same path it has since time immemorial.

Renewable Resource: People who visit Yuli notice that the families there all raise a fish neither colorful nor of interesting shape. Differing markedly from the colorful tropical fish raised by people on the west coast, these fish are in fact Varicorhinus alticorpus, a species unique to Taiwan, that have been pulled out of the Lele River. Although there are regulations against keeping rare species, the conservation laws have to adapt to "local needs and possibilities." "Just cast a line in the Lele, and you're bound to catch one," says a Yuli resident. The director of the Nanan Station of the Yushan National Park Administration confirms that the river has lots of Varicorhinus alticorpus.

In the Nanan Valley, which lies at the side of the Lele river, there is a nursery for raising stout camphor trees managed by the Forest Bureau's Yuli work station, where you can see Formosa Blue Magpies, rock monkeys and muntjac from time to time. "Wild boars often break down the fence," says Wu Chen-jung, of the Yuli station staff. Animals going down to the river to drink pass by here.

People also are relying on the river's water more and more. Now not only has Changliang built a dike for irrigation, but several boroughs in Yuli township on the east bank of the Hsiukuluan River also rely on drawing water from the Lele to supplement their irrigation water during the dry season.

The Lele is one of three rivers in Hualien County with enough water power for a hydroelectric plant. Downstream of the Luming nursery of Chohsi rural township, along the lower stretches of the river, the current is very rapid. "Canoeing is just as exciting here as it is on the Hsiukuluan River," says Wu, who seems not to have had enough of it.

The Old Home Town Changes: The Chingshui river was also once teeming with life. How is it that in a short time, it has all been used up, and the river has been declared "hydrologically dead?"

One hundred and fifty years ago when the camphor industry earned a reputation as the "world's best"--a first for Taiwan--the Chingshui River contributed much of its virgin stout camphor forests along both banks. But the large-scale felling of the forests didn't begin until the era of the Japanese occupation, when the Chingshui and Changliang forest roads were completed, connecting upstream areas of the river. And the forests were the source of the water. With its environment disturbed, the Chingshui began to walk the road to death.

In the 1960s the government struggled to obtain foreign exchange. Under a policy of forcefully pursuing industrial development, record numbers of trees were cut. In 1960 the Yuli Forest District Office was established, and the forest compartments upstream continued to send down such top-grade conifers as red spruce and cypress and such broad-leaved trees as the Nanmu and Formosan Michelia.

The boss of the Hsiehho mill, Chiou Hsien-tsung, remembers that in the 1950s and 60s each forest compartment would be given an area of about 200 hectares and a hundred workers. Around 10,000 cubic meters of forest would be cut in a year. "There would be as many as 10 or 20 workers just responsible for maintaining the roads," he recalls. Almost all of Yuli's laborers of that era worked in the forests and the river was often full of floating logs. "When we were little, we'd go down to the river, pick out a log and ride it to our homes by the Hsiukuluan," says Wu Chen-jung.

From What's on the Land to What's Under It: Truck after truck and train after train of logs would head north out of Yuli to Hualien, where the lumber would be shipped to the west coast or abroad. It went on like this for 20 years until the 1970s--when Taiwan's economy started booming and agriculture gradually took a back seat to industry. In Yuli the trucks hauling lumber were replaced by those hauling serpentine from the quarries.

In the sixties, the east coast had already began exporting marble and ornamental rocks. Most of the rock used for the Ocean Park of Okinawa originated here. Even more resistant to acid than marble and highly prized in furniture, serpentine did not have the good fortune to avoid this second assault, and the serpentine along the Chingshui River was picked clean.

"The river bed was our quarry. We just picked the serpentine we wanted, then lifted it and transported it away." Local residents remember vividly the Chioupao Company, which made the savvy move of applying to mine here first. "Without spending anything, they became rich overnight," say Yuli residents unanimously.

The Days of Prosperity: When the stone downstream was exhausted, the miners went upstream. In 1971, 16 mining companies applied to begin mining the 1500 hectares of Chingshui valley. "At the peak, there were 300 to 400 miners digging in the Chingshui valley and 30 trucks that could each hold 30 tons of rock," says Liu Bao-ching, a supervisor of mining there. In the 20 years since, three-fifths of the serpentine mined in Taiwan has come from this valley.

As lumber and rock were being pulled out of the Chingshui area in full force, the chief residential center of the area, Yuli, which had been a simple little town, prospered to become the east coast's lumber center and third largest city after Hualien and Taitung.

Chen Ching-chi, secretary of Yuli Town Hall, points out that at the peak--after the mining was in full swing but before the logging had gone -- the town had a population of 70,000, twice the current figure. At the time, there was a large population of outsiders, including buyers for lumber companies of Taichung, Kaohsiung and elsewhere. In order to make it convenient for the businessmen who came to negotiate, a branch of the Land Bank was also established there, based at the tiny Yuli train station. "There were more than 20 hotels and dozens and dozens of rickshaws," notes Lin Shou-chang, who runs the 100-year-old Pusheke hotel.

Unconquerable Mountain: In this time of glory for the Chingshui River and Yuli, all was quiet by the Lele. It certainly wasn't that the river lacked natural resources--the middle and upstream stretches of the Lele abound in precious lumber, and the Taiwan Provincial Bureau of Mines discovered abundant deposits of white marble in Walami, along the middle stretches of the river. Thirteen companies applied to mine there and were itching to go.

The development of the Lele can in fact be traced back to the Ching Dynasty. Liu Ming-chuan, in order to connect the east and west coasts, dispatched a high ranking military officer, Wu Kuang-liang, to lay the eastern portions of the ancient Patungkuan road along the Lele River. During the era of Japanese occupation, the Japanese also built the Patungkuan security road in order to control the local aborigines. But the river flows by an untamed mountain wilderness. When one adds to this dangerously wead geology and topography, the challenges to opening a road are great. Only a simple foot path leads into the area now. While the deposits some 30 kilometers from roads grabbed the miners' attention, there was no way they could transport the stone out, and hence the area around the Lele remained in its original wild state.

In 1977 the Taiwan Highway Bureau planned a new Cross Island Highway, the eastern portion of which would follow the mid and upstream sections of the Lele, running from Tafen to Walami to Yuli. Not only were many people in Yuli pleased that the new road would make transportation even more convenient, but many also looked upon the Lele as a door on a whole new land, through which one could enter at will. Hence, there were great expectations for the deposits at Walami, and the mining industry was ecstatic, eager to start.

Dead End: Fortunately, things did not go as expected. In 1985 Yushan National Park Administration was established, and to preserve its ecology and historic sites (the Patungkuan ancient road and ancient aboriginal areas) the Lele River area from Walami upstream was made part of the national park. In accordance with an assessment made by China Engineering Consultants, the Yushan National Park Administration decided that the land was unstable and liable to frequently collapse along the 50 odd kilometers of the planned cross-island route from Yuli to Tafen. The maintenance costs, they determined, were high and the economic value low. In addition, opening the road would damage nature in ways that would be impossible to amend. A report by the Department of Zoology of National Taiwan University commissioned by the park pointed out that great varieties of wildlife exist in the area between the Lele River and Hsinkang Mountain, including such mammals as the Muntjac and the Mikado Pheasant. The two banks of the river are home to such rare species of bird as the Maroon Oriole, the Black Eagle and the Mikado Pheasant. Building the road would create two separate wildlife communities, endangering propagation. After much consideration, the National Park requested a new appraisal of the risks of building a road, and construction was temporarily halted 14.5 kilometers out of Yuli.

In their development so far, the Chingshui and Lele rivers have met completely different fates.

The Social Value Is Totally Lost: At the end of the 1970s, forest policies were revised and the logging industry declined with the revisions. In the face of competition from imported stone, quarries also hit hard times in the eighties. Yuli now has only one lumber mill that cuts imported logs, and "there are only five or six hotels left of any size," says Lin Shou-chang, who runs the Pusheke.

Now that all the prosperity has left Yuli, the Chingshui, once a river that made it hard for people to leave, has not only lost its economic value but has also lost its "social value"--its value as a natural resource of the nation.

After so many years of heavy cutting in the forest, the Chingshui River has been seriously weakened, and the droughts and floods have been unending ever since. The added wounds made by the mining--the fact that the industry paid no attention to the techniques used--has added to the ecological disaster.

Because serpentine is characteristically scattered, it was necessary to open up the mountain to find the deposits. The domestic industry never got beyond the bomb-the-mountain-dig-the-mountain method. "They'd start with the lower slopes and dig until the whole mountain collapsed," said Liu Pao-ching. Although the Mining Industry Safety Inspection Association requested that miners take water and soil preservation measures and build retaining walls and dumps for the mining debris, in the Chingshui Farm these guidelines were totally neglected.

Yuli Flood Plain: At the beginning, miners applied to the Forestry Bureau to rent the land, and then the military transferred authority to the Taiwan Garrison Command for a criminal rehabilitation facility there, the Chingshui Farm, and the Taiwan Provincial Bureau of Mines was given responsibility for safety inspections. With control exercised by different agencies and the remoteness of the mines, mining safety laws were hard to enforce and the mining companies had free reign to interpret the law as they saw fit.

"Everyone was always behind with the digging," frankly states Liu Pao-ching, who worked in the Chingshui mines for many years. "Where was there time for retaining walls?" In the past, the miners would dump the debris into the river and would never proceed with replanting. "Fields downstream became submerged with the debris dumped by the miners," says Wu Chen-jung.

According to the registration book of the Taiwan Provincial Bureau of Mines, currently eight mining companies are working the Chingshui Farm, and every year they take out 70-80,000 tons. The last mining permit expires in 1995. "Yuli residents have met with great misfortune!" says the driver of the Forest Development Department who lives in Yuli and has seen with his own eyes the bare mountain of haphazard rock piles and heard with his own ears the sounds of blasting and rocks falling. He can't help but be concerned for himself.

"If one takes the estimate of 1.5 tons of sand and rocks for every cubic meter, several hundred million tons of erosion occurred in the middle and upper stretches of the river over the last few decades," says Huang Jui-hsiang, a native son of the east coast who is extremely concerned about the condition of the Chingshui ecology. The downstream river bed of the Chingshui is six or seven meters higher than it was 20 years ago and is now higher than Yuli. This makes Yuli a huge flood plain.

No Eggs for Yuli? Every year for the last three years, during the spring planting season, ducks have entered the rice paddies beside the Chingshui and Hsiukuluan Rivers in search of food. Farmers angry about trampled crops have set up flags and bird-catching nets and set off firecrackers -- exhausting themselves in the effort.

But in their anger, they don't realize that the source of their problems is yet again the destruction of the Chingshui. The erosion along the upper Chingshui, which is a tributary of the Hsiulukuan, has washed downstream.

The changes have destroyed the Hsiukuluan's shoreline water plant ecologies. Thus, the ducks that live on the river have suddenly lost their protection. "This is why the ducks are invading the paddy fields," says Hsu Pao-hsiung of the Hualien Agricultural Improvement Farm, who has performed a study on the matter.

Botanists are worried that the Chingshui poses another lurking threat to farmers. Because the coal content of serpentine is high, the ashes and dust that result from mining are carried down and enter the soil, posing a public hazard. Lien Hung-te measured the productivity of his fields, comparing those irrigated with water from the Lele to those irrigated with water from the Chingshui. In one crop, a hectare of the fields watered with the Lele's water could produce as much as 10,000 Taiwanese pounds of rice. Fields irrigated with water from the Chingshui, on the other hand, could only produce 6-7,000 Taiwanese pounds in the same area.

"You could say that the hens of Yuli do not lay eggs, and all we're left with is their droppings," says Chen Ching-chi indignantly. The lumbering and mining were done so the central authorities could collect tax, and the natural resources of Yuliwere emptied. "We didn't get any of the tax money to improve the place." And the economic boom that was brought along by the wave of people during the logging boom disappeared like sand castles in the surf with the industry's decline.

By Never Touching the Capital, the Interest Lasts Forever: The fate of the Chingshui is an example of how irresponsible pursuit of money can do irreparable damage to natural resources.

Let's look at that other river, the Lele. Because of the difficulties posed by its geography and topography and its recent inclusion in a national park, it is temporarily out of the reach of development. But there is much support in Yuli for building a road and opening the area up to mining. "I fear that sooner or later the movement for developing the wilderness will win out," pessimistically predicts Chiou Hsien-ming, a local reporter for the Liberty Times who founded the "I Love Yuli Workshop."

"In fact it's really quite obvious--there are only two ways to go," says Wu Chen-yu, the director of the Nanan station of the Yushan National Park. One road is the short-term profits of development that will lead to an ending like the Chingshui's--where nothing is left. And the other leaves the wilderness of mountains and river as it was--lush and pristine for eternity. Currently, the National Park has planned a downstream recreational area and a "Patungkuan Footpath." Tourists will be able to take day trips there and then return to stay in Yuli.

But if cars can pass through on a new cross-island highway, people will just drive through, passing Yuli in an instant. "It's like when the southern cross-island highway was built," he says. "At first everyone at the eastern starting point of Haituan was vigorously in favor of opening the road, thinking that people would be able to get to Taitung in only an hour, but since then the city has been in gradual decline."

Don't Let the Lele Become the Chingshui: Because of the dangers posed by the topography of the Lele River valley, it is thought that a road would be closed half of the time for repairs--thus eliminating the transportation advantages--whereas the damage to the water and the land would not be lessened. Some hold that if the best construction techniques were used, damage to the soil and water could be overcome. "First of all we want to see if there will be suitable economic benefits," says Chang Shih-chiao, a geography professor at NTU who is deeply concerned about the development of the river. Secondly, building roads and mining are structural activities. By examining past experiences and using current techniques, one can predict the results of construction in such a sensitive area. In addition, the by-products of civilization--the litter, fumes and polluted water--would be outside anyone's control. "The negative effects would be inevitable and impossible to make amends for once done!" Since the mining only benefits a small number of people, he holds that the heavy social costs make it "a losing proposition." "And the biggest losers of all would be our children and grandchildren."

Even if the final policy decision is for development, will people learn from the experience of the Chingshui to prevent once again the violent raping of the land?

Will the Lele River become another Chingshui River? And will Yuli thus be wiped off the map? It is time to test the wisdom of the people of this generation.

[Picture Caption]

A view of the Lele River stretching off in the distance where it converges with the Chingshui River near the village of Choching.

Area of Yushan National Park

Because of excessive logging and mining, the Chingshui Valley is given to landslides.

Destroyed by flooding, the hydrology observation station was moved from the shore of the river to the river bed.

The Forestry Bureau has announced a "100 Year Tree Plan" for the Chingshui Valley. (Left) Workers are measuring the distance between shoots in a mixed forest. Personnel from the Forestry Bureau who have come up the mountain to check on the speed of tree planting are eating with workers in their hut, exchanging thoughts about the planting of trees.

Surrounded by rivers and mountains, the township of Yuli now faces the danger of flooding because of the transformation of the Chingshui River.

In 1976, floods washed away Changliang and Kecheng--their good fields and villages. In the temple to the local deity on water resources land, the people of Yuli have laid bricks in the shape of the character for water. From time to time they will offer incense and pray that the floods won't come again.

The fields by the side of the Hsiukuluan in Yuli have also been affected -- at times being submerged by water or invaded by ducks.

Sand and rocks have plugged up the water inlets, and the Irrigation Association has built a simple dike so as to draw in water from the Lele River for irrigation.

Because of large-scale logging, the city became the logging center for the HualienTaitung area.

With logging and mining in decline, Yuli has become once again a small town with a declining population.

With changing times, new generation Hsu Kuo-liang (below right) has developed totally different management methods from older generation Hsu Wang (above left).

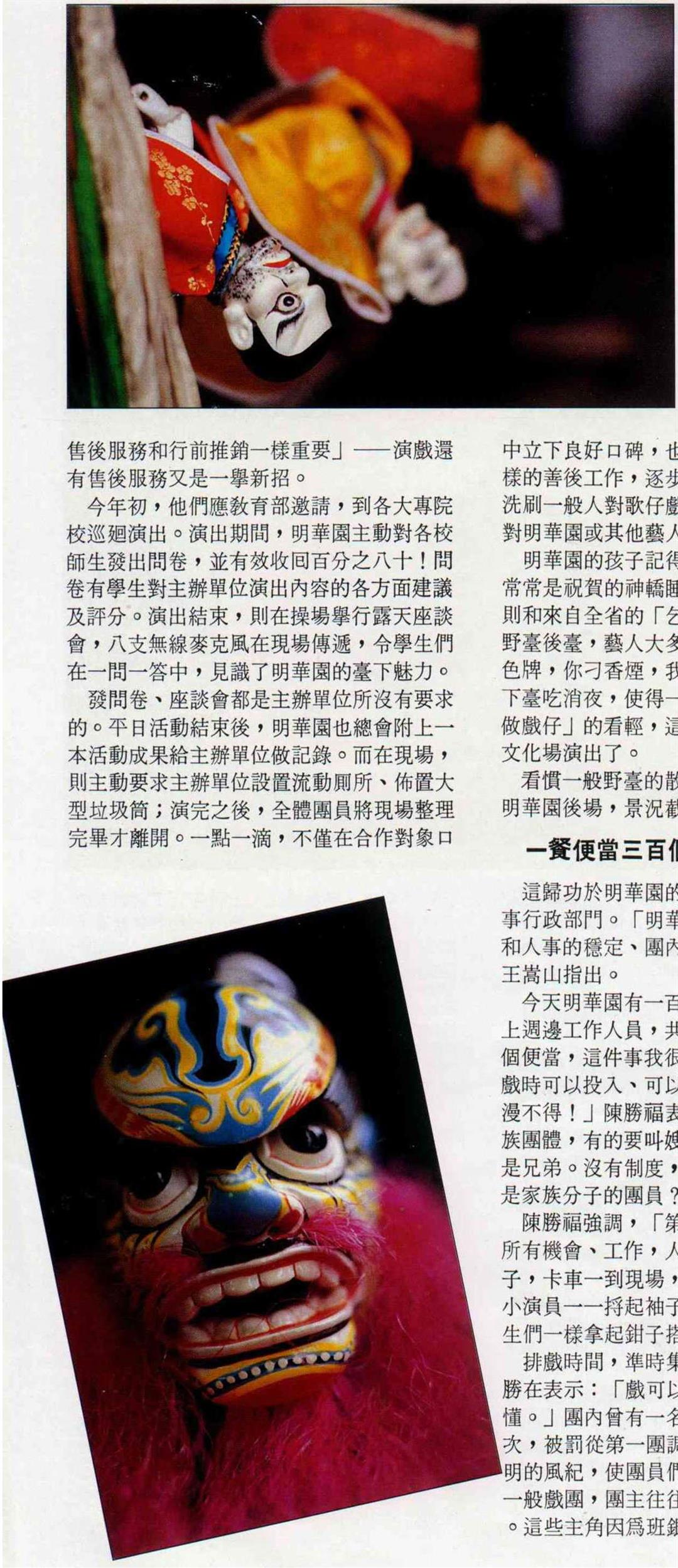

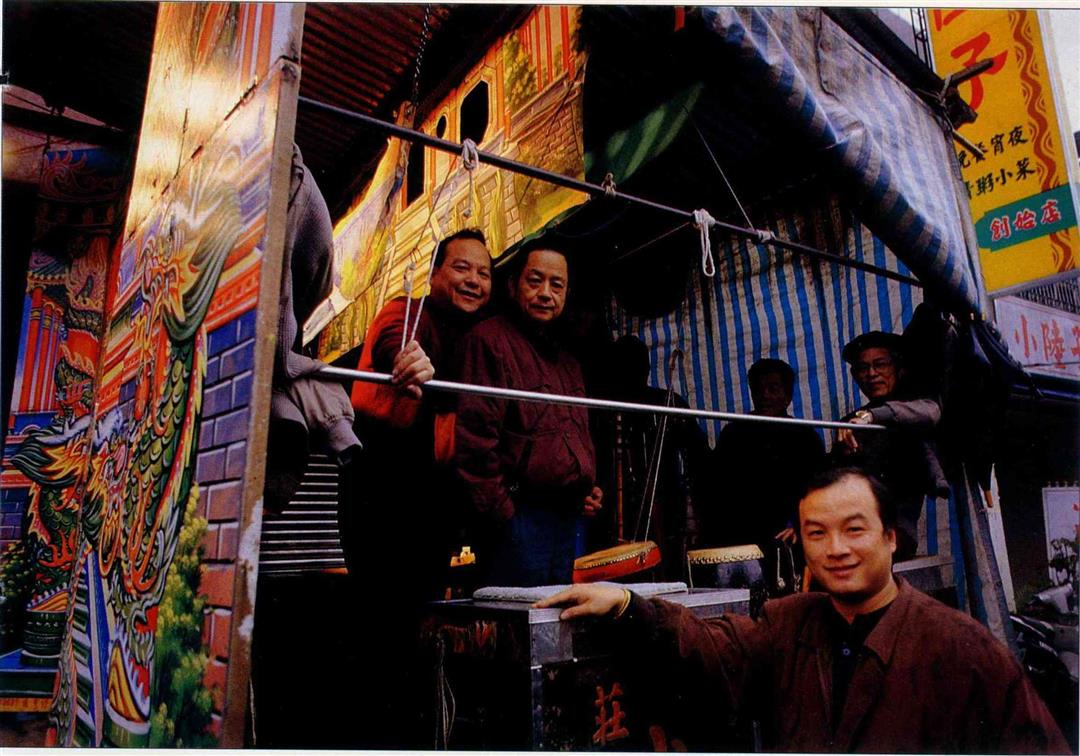

At the 7th Living Heritage Awards gala evening, the Ming Hua Yuan recount the history of folk opera in dramatic form while celebrating the award won by their old troupe leader Chen Ming-chi. (photo by Diago Chiu)

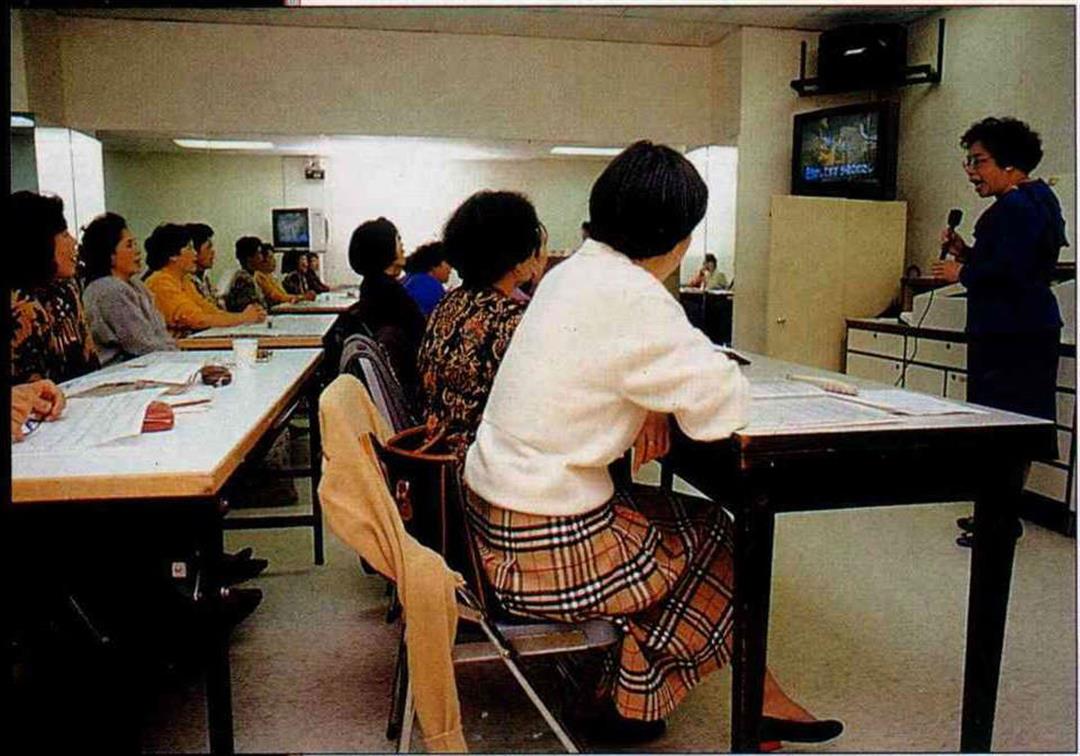

Besides learning the fine points of singing, you can also make new friends in karaoke class.

Karaoke has become a "national pastime" in Taiwan, and even government officials like Minister of the Interior Wu Po-hsiung (right) often enjoy getting in on the act.

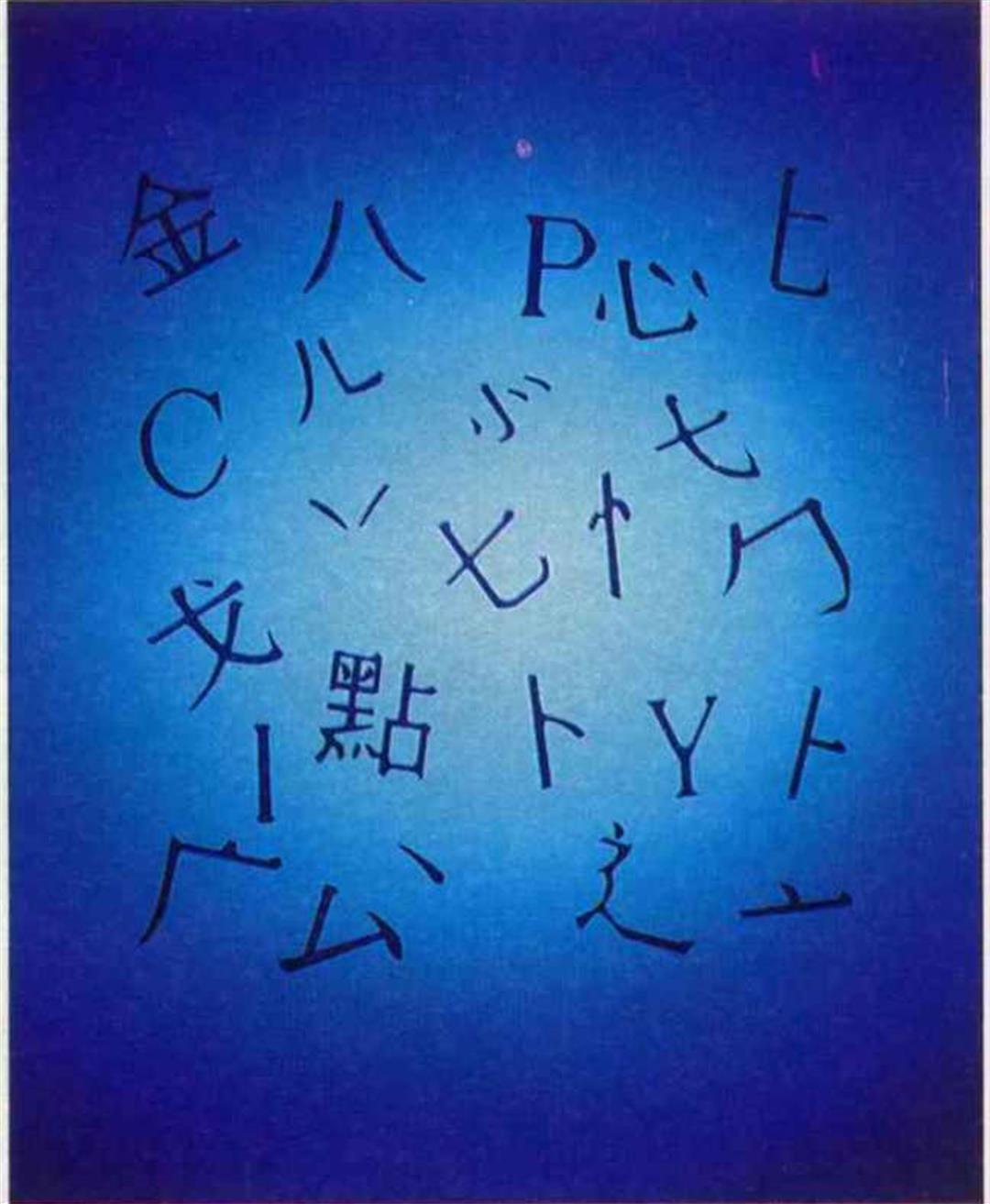

(Above left): Chu Bong Foo toiled for six years to develop Chengi.

(Below left): Taking a breather from the dry rigors of work, he has fashioned a miniature bicycle out of wire.

(Right): Chu Bong Foo (seated in the middle) spends his days with his head buried in computer research, working with a group of young friends who care for neither fortune nor fame.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)