Traces of Time:

BURSTT in a Space Race

Joanna Wang / photos Kent Chuang / tr. by David Mayer

January 2026

As we hike with a group of scientists along the banks of the Hapen River in Yilan’s Fushan Botanical Garden, suddenly a clearing in the valley comes into view. Standing upright on a platform are over 200 neatly laid out metallic antennas, shaped rather like two-dimensional Christmas trees. At first glance they look like an array of magical artifices in some sort of fantasy novel.

Senior Research Engineer Dr. Li Chao-te (left) and Engineer Cheng Jen-chieh (right) are the BURSTT team members in charge of front-end operations.

Small but powerful

These antennas make up the main array of the Bustling Universe Radio Survey Telescope in Taiwan (BURSTT). There are currently 256 antennas in the array, which is still being expanded. Though the array may not look all that imposing, when all of the system’s components are working together properly, explains postdoctoral fellow Wang Shih-hao, “it functions just like a very large telescope.” If the main array could be moved to a site big enough for a 4096-antenna array, reception would become significantly better.

Senior Research Engineer Dr. Li Chao-te (Above) and Engineer Cheng Jen-chieh (below) are the BURSTT team members in charge of front-end operations.

Keys: Wide angle and localization

Launched in 2022, the BURSTT project is sponsored by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (ASIAA), which is overseeing the joint efforts of National Taiwan University, National Tsing Hua University, National Chung Hsing University, and National Changhua University of Education to build a new-generation wide-angle radio telescope specifically designed to survey FRBs and achieve precise localization.

Traditional dish telescopes are built to reach into deepest space, but the BURSTT project is based on different thinking. BURSTT relies on an automated wide-angle antenna array that continuously monitors one-quarter of the sky in search of sudden FRBs.

At the same time, by setting up a number of outrigger arrays around Taiwan and offshore, the BURSTT team is able to carry out very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) localization. The idea is to identify the galactic source of an FRB at the moment it is detected.

In addition to the main array within the Fushan Botanical Garden, which straddles the boundary between New Taipei City and Yilan County, the BURSTT project has domestic outrigger arrays in Green Island, Nantou, and Kinmen, and is arranging international sites for outrigger arrays in Japan, South Korea, Hawaii, and India. Starting off in Taiwan and its offshore islands, the BURSTT project aims to build a cosmic radio telescope that spans much of the globe.

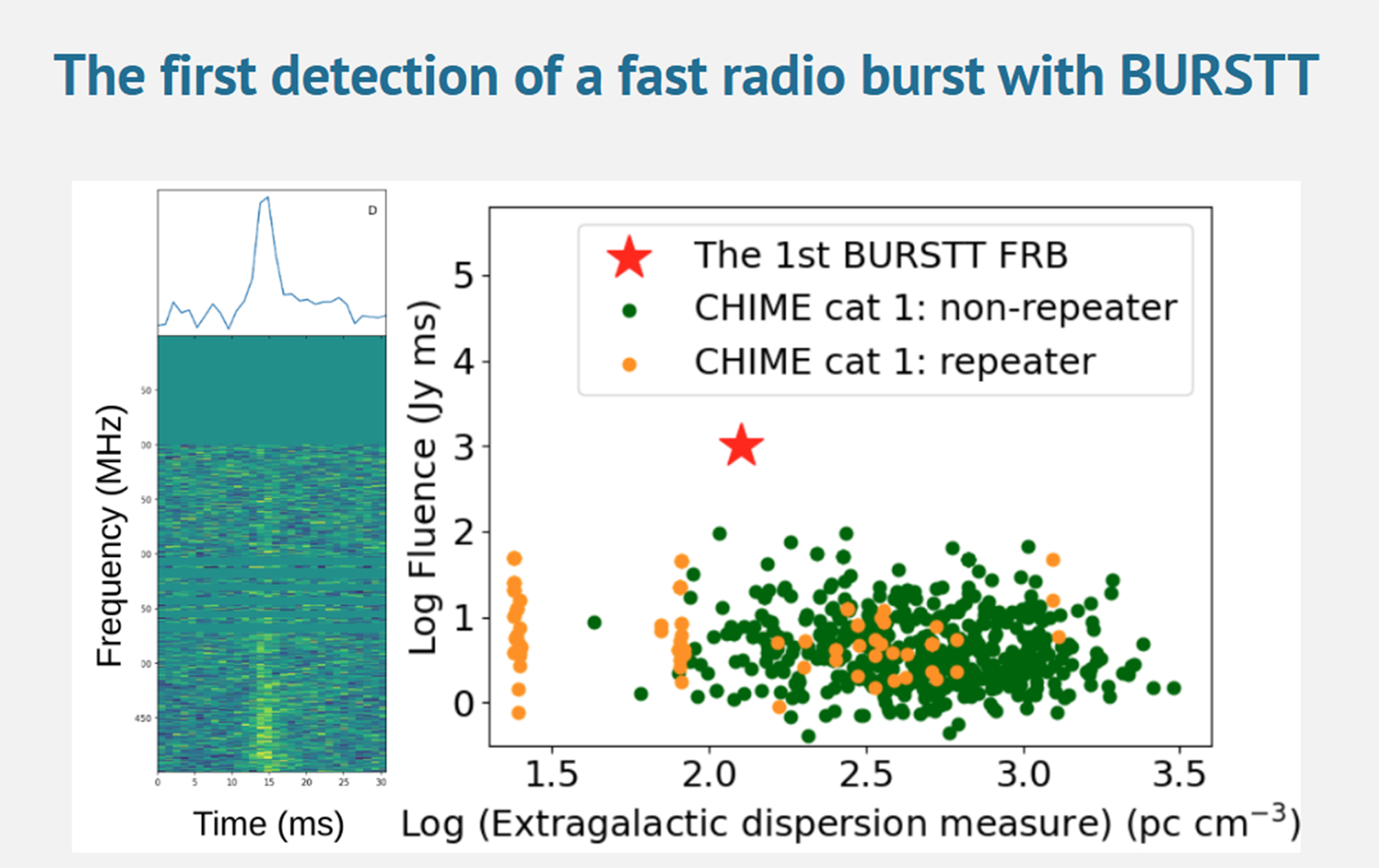

BURSST’s first FRB detection: The left image shows the frequency characteristics. The red star in the right image represents the first FRB detected by BURSTT, which is contrasted with FRBs logged by Canada’s CHIME radio telescope. (screenshot from BURSTT website)

BURSTT detects its first FRB

BURSTT began operating in 2025 and detected its first FRB in July of the same year. South Korean postdoctoral fellow Eie Lee Sujin received a notice from the BURSTT system at 5 a.m. while traveling overseas, and thus was the first team member to learn that an FRB signal had been captured. Another team member, Dr. Lin Kai-yang, recalls that everyone was very excited and they threw a party to celebrate the occasion. Only the main array detected the FRB, while the outrigger arrays did not, so it wasn’t possible to localize the source, but the team felt confident they would soon be frequently finding FRBs and would thus maintain their competitive edge in the international scientific community.

Made in Taiwan

BURSTT program director and head of the ASIAA Pen Ue-li notes that the program was able to get up and running in just three years thanks not only to the team’s great expertise and dedication, but also the maturity and flexibility of Taiwan’s electronics industry. The ability of domestic firms to quickly produce the antennas and other hardware needed for research has facilitated a close integration between the “front end” (antenna deployment) and “back end” (data analysis) of the undertaking. This smooth meshing has been key to the BURSTT project’s quick success.

The BURSTT main array is located inside the Fushan Botanical Garden.

Keeping an eye on the sky

“What determines whether a project is a success, is whether it has opened up a new path for us.” Dr. Pen says the BURSTT project hasn’t just created a new way to study FRBs. He also hopes that other teams around the world will join in on what BURSTT has started in order to build a “whole-sky, all-weather” global observation network that works around the clock.

That has to be the approach, because the next FRB might bring special clues that could help us to better understand the universe.

BURSTT back-end data analysts (left to right): Dr. Wang Shih-hao, Dr. Lin Kai-Yang, and Dr. Eie Lee Sujin.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)