The Lingering Local Flavor of Taiwan's Small Towns

Teng Sue-feng / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Scott Williams

February 2006

Fifty years ago, the fruit from a single coconut tree in Pingtung was worth enough to support a university student. Thirty years ago, more than 70% of the residents of Nantou's Chushan Township worked in the bamboo processing industry. Twenty years ago, ceramics exports from Taipei's Yingko Township reached a record NT$20 billion and Yingko had the highest rate of Mercedes Benz ownership on the island. But times change, and so too has the structure of Taiwan's economy. One by one these townships have surrendered their once lofty positions in the island's economic hierarchy.

Rural industries aren't like manufacturing or high-tech industries. They aren't continually plagued by worries about major international firms cutting back their orders, management relocating factories, or global trade sanctions. Instead, they are more like an old tree--insects may gnaw their fruit, but they cling tenaciously to life. Given a little fresh water, they reveal a new side, gain new worth, and may even once again revive Taiwanese industry.

With its ridges of emerald hills and scatterings of gauzy mist, Sun Moon Lake in Nantou County's Yuchih Township has long been a renowned tourist destination. In contrast, visitors to the area have typically regarded the township's Seshui Community as a mere rest stop on the way to the lake. This is unfortunate because the township is home to a forgotten bit of history--during the Japanese occupation, it produced the black tea drunk by the emperor. These days, local residents are busily clearing away the cobwebs and creating new brands in an effort to make Taiwanese aware that the best black tea comes from Yuchih.

Yuchih black tea's moment of glory passed; 30 years ago, it began to go into decline. Tea farmers attempting to increase their output began processing old leaves together with the new. As a result, quality declined and they lost their European export markets. Matters got worse when they abandoned hand harvesting in favor of less-expensive machine harvesting. The machines mowed the tea plants like grass, effectively giving the plants a crew cut and mingling stems with the leaves. Faced with shrinking markets, many farmers gave up their tea plantations entirely and turned to growing the more profitable betelnut.

Taiwan's small towns are home to a rich economic legacy just waiting to be uncovered. During the Japanese colonization, the emperor drank fine black tea from Nantou's Yuchih Township. The photo shows a tea field belonging to the Yuchih branch of the Council of Agriculture's Tea Research and Extension Station.

The scent of tea

These days, if you take Provincial Highway 21 into Seshui the only tea plantations you'll see are squeezed into the breaks between the betelnut groves that cover the hills and valleys of the area. Production has not been well managed, so prices are not nearly as good as they used to be--local growers typically just sell their new leaves to nearby processors. The situation is, however, improving, albeit slowly.

Six years ago, the Chichi earthquake leveled 35 of Seshui's 48 homes. Losses were very heavy, but locals wasted no time bemoaning their fate. Instead, they immediately formed a reconstruction committee which chose to rebuild the local economy by reviving the black tea and pottery industries on which the area had once depended.

The Yuchih branch of the Council of Agriculture's Tea Research and Extension Station (TRES), which is located on the shores of Sun Moon Lake and has been developing new varieties of black tea for 70 years, was instrumental in returning Yuchih black tea to the market. According to Huang Cheng-tsung, head of the Yuchih branch's Tea Processing Section, discussions with local tea growers led the branch to conclude that "local industries should have a Taiwanese flavor." The section therefore selected a cultivar called TTSE No. 18, a cross between a wild Taiwanese tea and a Burmese tea, for the local production and marketing group.

TTSE No. 18 produces a light reddish-brown brew that has a natural cinnamon scent and a slightly minty flavor. Consumed unsullied by cream or sugar, the tea's rich, sweet flavor is readily apparent.

Seshui's Tayen Village formed the No. Six Production and Marketing Group under the guidance of the Yuchih TRES branch three years ago. The group's objective was to produce a unique, high-quality organic tea and market it under their own brand name. It would be an exquisite black tea made from the tenderest flushes, hand-picked in spite of the cost.

According to Yeh Chin-lung, the head of the group, back in black tea's glory days, Yuchih had about 1800 hectares in tea versus only some 400 hectares today. Tayen Village currently grows black tea on 60 hectares, ten of which are given over to TTSE No. 18. Two years ago, Yeh used small and medium-sized enterprise start-up funds from the Ministry of Economic Affairs to construct the tea processing plant where he now produces Forest Black Tea, his own brand of handpicked organic black tea. Yeh produced only 4,000 kilograms last year, but, at NT$2,000 per catty (600 grams), it is priced on a par with high-end imported black teas.

Glass beads are considered one of the three treasures of the Paiwan people. The lines on the beads represent the blessings of the tribe's ancestral spirits. The photo shows work of Shih Hsiu-chu, one of the founders of the Dragonfly Yachu Studio in Pingtung County's Santimen Township.

Local gems

The scent of tea lingers in Yuchih. The climate--large day and night temperature differentials and a lot of fog--and the acidic local soil are still just right for top-quality black teas. The community now anxiously awaits recognition and support for its new brand from Taiwan's public.

Taiwan has 319 rural townships like Yuchih. In the 1950s and 1960s, agriculture was the backbone of Taiwan's economy, and many areas relied on the large sums of foreign exchange agricultural villages earned. Later, when changes in the economy sent agriculture into decline, traditional villages began decaying as their populations dispersed.

Over the last dozen or so years, while most people's attention has been on the export-oriented information-technology industries, government agencies have been working hard to revive rural economies. With more and more manufacturing being outsourced to China, the government's objective is to boost rural economies. To that end, it has developed a number of transministerial and transdepartmental programs, including the Ministry of Economic Affairs' Commercial District Development, Trading Area Renovation, and Unique Local Industries projects; the Council for Cultural Affairs' Comprehensive Community Building and Industrialization of Culture, Culturization of Industry projects; and the Council of Agri-culture's One Town, One Product project. Under their guidance, 101 local industries have so far been revived and now sparkle like fine gems in each of these areas.

The premises underlying the effort to invigorate township industries are that Taiwan's townships need money and people flowing into them again; that they cannot continue to engage in poorly paid contract manufacturing; and that the only ways to return small towns to prosperity are to combine unique local industries with tourism, or to treat high-tech research and development as a "traditional value."

Lai Sun-quae, director general of the MOEA's Small and Medium Enterprise Administration (SMEA), offers an example: Fifty years ago, the produce of a single coconut tree was worth enough to support a university student. Today, vendors sell the juice and meat of a coconut, but throw the rest away. To Lai, this is both wasteful and environmentally unsound.

Four years ago, the SMEA, together with teams from Pingtung University of Science and Technology and the Kaohsiung District Agricultural Research and Extension Station, took the coconut growers of Pingtung's Laochuangchiao Community under their wing. They began by developing coconut processing equipment that separates coconut fibers, shell, meat and juice, then went on to create several new products, including coconut essence, a coconut liqueur and a mattress that breathes. They also used the coconut shell to make a number of handicraft products, including wind chimes, flower pots, and sound boxes for erhus (traditional two-stringed fiddles).

Bamboo is perhaps Taiwan's most vigorous plant. In addition to being used in construction, it can be carbonized and used in fitness products. The photo shows the bamboo kiln in Miaoli's Shihtan Township, which processes four-year-old Moso bamboo.

Star industries

Taiwan struck rural gold again with the new Phyllotex brand of bamboo charcoal products just announced by the MOEA's Department of Industrial Technology and the Taiwan Textile Research Institute. This new technology, jointly developed by the Taiwan Forestry Research Institute and the Industrial Technology Research Institute's (ITRI) Materials Research Lab has given Taiwanese bamboo fantastic new applications.

Recognizing that bamboo charcoal has a long history in Japan, the ITRI invited a Japanese master named Akemi Toba to Taiwan two years ago. When he arrived Akemi began teaching his techniques for constructing earthen kilns and burning bamboo, as well as helping local researchers overcome other difficult technical hurdles. In the process they developed, bamboo was first carbonized at high temperature. The resulting charcoal was then ground into nanoparticles which were blended with polyester granules to form polyester chips. These chips are then drawn into a thread that is woven into fabrics which can be used to make socks, undergarments, and sportswear.

Bamboo charcoal fabrics have become stars, the "black diamonds" of the health products industry. Their fine weave, high porosity, and large surface area give them exceptional moisture absorbing, antimicrobial, and heat-retaining properties. They also generate healthy anions.

Taiwan's bamboo forests are estimated to cover 150,000 hectares, or about six times the area of metropolitan Taipei, and include some 24 varieties. Because bamboo plants grow so much faster than trees, and can typically be harvested for use after only four years, some people refer to these forests as "bamboo mines."

Taiwan currently has three bamboo charcoal kilns: in Miaoli's Sanwan Township, in Nantou's Chushan Township, and in Chiayi's Tapu Township. Technologically transformed by these kilns, bamboo that was originally worth less than NT$5 per kilogram turns into material worth more than NT$1,000 per kilogram.

At a recent press conference, Minister of Economic Affairs Ho Mei-yueh stated that Taiwan's NT$12.5 billion export textiles industry could no longer continue to compete on price, and argued that the industry needed a revolution that would take advantage of new materials and new brands to find a path forward.

Tai-Hwa Pottery provides artists with the latitude to experiment with new looks for ceramics. The photo shows the work of Cheng Shan-hsi.

Kiln burns for a century

Newly emerging industries typically must rely on the government for capital for technological research; their own resources are insufficient. But abandoning their long-standing contract manufacturing model of business and opening up new markets requires that firms also become bolder and more willing to try new ideas.

Tai-Hwa Pottery, sometimes called Yingko's Palace Museum, is Yingko's top pottery brand. The innumerable pieces fired in the fierce 1,000oC heat of its kiln each year generate sales of more than NT$100 million. What is Tai-Hwa's secret?

Lu Chao-hsin, the 50-ish chairman of Tai-Hwa, came to Yingko by way of marriage, and established Tai-Hwa in 1983 after leaving the construction industry. Like many of Yingko's pottery makers, Lu built his business selling pieces done in antique white and monochrome glazes. But Lu sensed a crisis coming and changed his approach. He explains that he once turned down an order from a European hyper-market for ten million custom-made ashtrays simply because "the order would have turned us into a downstream manufacturer. Our staff would have been rushing to fill orders every day without any sense of creativity. And what would we have done if we lost the account?"

Looking at his industry, Lu noticed that when visitors came to Yingko, they usually just bought their ceramics then left; they didn't interact with the town at all. The situation was exacerbated by the attitude of local firms, many of which were unwilling to let their customers look around for fear that they might pick up their trade secrets. Lu decided to take a different approach. In 1995, he built a ceramics learning center with space for 100 people above his exhibition center. The center let elementary-school students and their teachers, as well as foreign and domestic tourists, feel the texture of the clay and the heat of the kilns for themselves. Tai-Hwa even allowed them to make their own pieces, which it would fire and mail to them after they left to help them recall their visit to Yingko. By providing visitors with such memorable experiences, Tai-Hwa inadvertently became part of the do-it-yourself trend.

Many years ago, when he was preparing to take his company in a new direction, Lu visited pottery centers in Guangzhou and Yixing hoping to learn something from the old masters of the trade. He learned instead that Yixing had become a contract manufacturer and had nothing new to teach. He then went looking for talent in other fields. "The ceramics industry isn't like the tech industry," says Lu. "It doesn't attract the kind of manpower chip-makers do. There aren't enough people who can do R&D and innovate. But by forming alliances with other industries, we have increased the variety of looks and glazes." Tai-Hwa began inviting painters, calligraphers and seal carvers to the factory, where it gave them the freedom to play with patterns and experiment with new ideas and polychromatic surfaces.

Seven years ago, Lu spent NT$10 million to build his Arts Center. Through the collective efforts of Tai-Hwa and several hundred artists, it has become a magnificent studio. Lu lifts up an NT$8,000 coffee cup-and-saucer set hand-painted by artists Cheng Shan-hsi and Kuo Bor-jou, each piece of which is absolutely unique. "Taiwan is second to none in terms of creativity," says Lu. "These cups don't need a sales pitch; they sell themselves."

Although Taiwan's plethora of rural industries offer no single model for success, they have faced many of the same difficulties: low levels of investment, high labor requirements, too little attention from society, little ability to attract manpower, and an inability to adapt and accumulate management skills. Developing the creative designers and salesforces instrumental to building a distinctive market position has also proved to be a challenge.

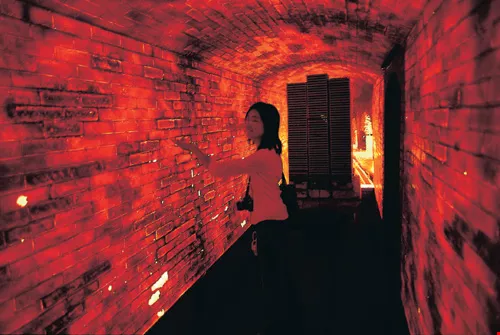

The Taipei County Yingko Ceramics Museum, which opened in 2000, is a testament to Yingko's long ties to ceramics. One area of the museum uses red lighting to represent the 1,000oC heat of the kilns, giving a sense of the firing process.

Preserving the flavor of the past

Marketers, on the other hand, feel that these difficulties are not the heart of the problem.

Wu Jing-hong, who worked for Taiwan advertising giant United Advertising before founding Tao Collection nine years ago, once considered bringing representatives of all of Taiwan's specialty foods manufacturers together in an exhibition hall at CKS International Airport. Wu wanted to bring tourists closer to Taiwan by giving them gift baskets containing samples of foods originally available only to those who traveled to the region in which they were produced. The packaging and marketing strategy he envisioned would involve a TV program modeled on Japanese shows about master chefs. The show would travel to the areas where specialty foods were produced, film the process, then provide tourists with information about where to go to try these foods for themselves.

Friends in management pointed out that, while the idea was good, he was likely to encounter two practical difficulties in implementing it: First, given how accustomed rural companies were to their old ways of doing things, would they be able to maintain the quality of their products if sales increased? Second, what would he do if the companies no longer wanted him to represent them after their sales increased?

Wu's misgivings were confirmed by an experience he had a few years ago. He had helped a company that produced free-range chickens develop a brand, which he heavily promoted in the run-up to the Lunar New Year. As he had anticipated, sales were very good. But, as soon as the holiday passed, the company decided to stop supplying him. It again became its own sales representative, and left Wu in hot water with a number of distributors.

Those rural firms that are already up and running aren't accustomed to the sales and marketing methods employed by mature industries, which is likely why professional marketers have had a hard time developing relationships with them.

"Whether you're talking about branding or sales," says Wu, "both involve bringing a tangible product or an intangible service to the attention of the public. But the product's quality provides the key support. What gives a product its local character is that local people used local materials, local skills, and their own passion to create a product that tastes as it always has. How you market it isn't even an issue."

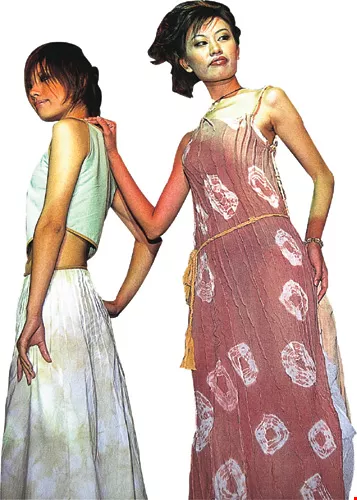

In Nantou's Chungliao Township, a group of mothers goes into the forest to pick leaves to dye fabric, from which gorgeous garments are created.

Welcoming local passion

In 2004, the Ministry of Economic Affairs provided guidance to 380 companies in 18 rural industries. The total revenues increased NT$130 million from the preceding year. They also created or maintained some 1,400 jobs, more than 400 of which were new job opportunities.

Most of these companies were small- and medium-sized enterprises--some were even micro-enterprises involving fewer than five people--that the MOEA hopes will ultimately become the driving force in their local economies. Though there remain many needs, rural employment opportunities are looking up and may even draw people back to the townships. It's just going to take some time.

Yuchih's high-end black tea production and marketing group currently has fewer than ten members, as many farmers are maintaining a wait-and-see attitude. Their concern is that they won't be able to bring in a harvest and generate an income for at least three years after they renew their tea plantations and institute new management practices. If the black tea market evaporates in that time period, all their labor will have been for naught.

"Few local specialty products have succeeded in going global," says Wu Se-hwa, a business professor at National Chengchi University. "Taiwanese products are going to have an even more difficult time because Taiwan hasn't shown a great deal of ability to internationalize its brands. Rural uniqueness is 'localized'; we should connect it to tourism. If tourism heats up, rural products will sell well." Wu recommends that businesses think beyond selling their products, that they incorporate new ideas from the "experience economy" and culturally innovative industries. They should start by building up the local character of their towns so that tourists want to spend time there. "If rural businesses can understand how tourists think, what they've come to see and what locals can provide to them," says Wu, "it opens up a lot of new possibilities."

Black bamboo charcoal becomes a cute gift when you draw a pattern on it and turn it into a hanging ornament.

Small is beautiful

Wu thinks that young people will remain in the townships if you can provide locals with a sense of mission and jobs in which they feel pride. For Wu, this pride grows out of a sense of the uniqueness of one's local culture.

In this respect, the SMEA's greatest success story is that of Shih Hsiu-chu, a member of the Paiwan tribe in Pingtung's Santimen Township.

Shih was originally a teacher at the village pre-school. When she became concerned that the tradition of manufacturing glass beads would be lost, she, her husband and her brother-in-law established the Dragonfly Yachu Workshop.

Because there were no written records of the Paiwan's ancient bead-making process, Shih and her husband were forced to make guesses about the tools and materials they used. Not surprisingly, they burned any number of beads (and, frequently, their own hands) when they were getting started. Later, misfortune struck when Shih's husband met an untimely death. Left to go it alone, Shih has now poured 20 years into the project. Though she makes only just enough to get by, her studio now employs 30 people, all of whom feel strongly that the preservation of tribal tradition is an honorable pursuit, as well as one that fosters their autonomy.

In Small Is Beautiful, the British economist E.F. Schumacher proclaimed that economic development, the complexity of human life, the pursuit of efficiency and productivity, and human tolerance for ever-finer divisions of labor could all only be pushed to a given point. In the 30 years since his book came out, Taiwan has experienced booming economic growth, become a highly capitalized and highly technologized IT powerhouse, and offshored its factories in response to global competition, the net result of which is that Schumacher's words seem even more profound than before.

Schumacher's contention that "small is beautiful" is a long way from the pursuit of "maximization" that is at the heart of today's mainstream economics, but is very much in line with the cultural values of rural industries. Where the highly variegated division of labor of capitalist societies tends to increase the distance between people, specialized local products, which are hard to standardize and difficult to produce in volume, tend to draw them closer to one another and bring them closer to the land. These products also forge close ties between producers and consumers because what is being bought is not a commodity but a life story that preserves the flavors of the past.

Yingko's Fortune and Wealth Pottery Place Art Restaurant offers patrons an exciting blend of the visual and the culinary by serving its fine food on ceramic flatware.

The story of tea in Taiwan is written in sev- eral splendid chapters, such as in 1916, with the Japanese colonial government's discovery of wild tea growing in the mountains of Kaohsiung's Fengshan Tropical Experimental Agriculture Area. This tea's leaves were about the same size as those of Assam tea, and it was welcomed like a precious treasure by Japanese tea masters. Using simple machinery they were able to process it, and after processing it turned out to have both a scent and color superior to northern Taiwan's tea.

In 1926, the Japanese brought in pure, large-leaved Assam tea from India, and dispatched tea specialists to inspect the Taiwanese geography, soil, and climate, finally deciding to cultivate the tea in Nantou County's Yuchih, Puli, and Shuili townships.

In 1930 the major tea producing areas of the time--India, Ceylon, and Java--together negotiated limits on tea production. As these restrictions went into place, Taiwan's tea industry seized its chance. Exports jumped to 3.29 million kilograms, and Oolong and Pouchong tea became popular. During this time, tea from Yuchih was not only offered to the Emperor of Japan as a gift, but also exported in large quantities to America, Britain, and Hong Kong. 1936 saw the establishment of a tea laboratory in Yuchih, which became the center of research into large-leafed teas in Taiwan, and a fountainhead of tea varieties in the island.

After World War II, the Kuomintang government took over the tea industry in Yuchih, handing over operations to the Taiwan Tea Company, which proceeded to get the plantations in order again after the disruption of the war. By 1961, the amount of land on which Assam tea was being grown in Taiwan had reached over 1800 hectares, with Nantou's plantations accounting for 1700 of those. In the 1980s tea plantations covered 38,000 hectares nationwide, but Assam had shown no noticeable increase, as the government had put more funding into partially-fermenting oolong teas, which were more suited to the local palate.

As the Taiwanese economy took flight and individual incomes rose, some farms started to see a drift away from farm work, leading the tea industry into a gradual downward slide. The export market was insufficient for survival, and so experts turned to research, improving oolong tea techniques, and along with an increase in the appreciation of tea preparation and drinking as an artform, a trend toward-high priced oolong tea took hold across Taiwan.

Production methods are roughly the same for oolong tea and black tea, with both going through drying, rubbing, splitting, fermenting, and drying. However, black tea produced during the summer and autumn is of better quality than oolong tea: because of the strong summer sun and high levels of catechu, the tea is stronger and more fragrant.

At the moment, over 80% of Taiwan's tea production is large-leafed hybrids. With current crops aging, if the farmers can switch to new breeds, it is forecast that production quantities and tea quality could rise noticeably.

(Teng Sue-feng/tr. by Geof Aberhart)

The unique indigo-dyed fabrics from Taipei County's Sanhsia come in shades ranging from pale to dark.

In 1804, Fujianese man Wu An and his family traveled across the Taiwan Strait and settled in Yingko, where they began producing ceramics from local clay in their own covered kiln. In the late 1800s and early 1900s more ceramics masters immigrated from Fujian, bringing with them techniques for firing in large-scale brick-built kilns. Later, during World War II and the ensuing shortage of manpower, the industry saw increasing use of electrical machinery.

After the war Yingko's ceramics industry began to flourish, moving into products for construction and bathrooms. With direct transport between China and Taiwan being cut off after the civil war, the China-Japan ceramics trade was also cut off, and Yingko stepped up to the plate to fill this new hole in the market. Thus, from the 1950s production methods began to modernize.

In the 1970s Taiwan's imports and exports of ceramics grew tremendously, and with the US dollar low and the yen high, businessmen had a wealth of overseas business opportunities. In 1987, the industry hit a record high, pulling in over NT$20 billion. For 20 years Yingko enjoyed a golden age of exports as ceramicists took to emulating the ancient pottery styles.

Later, as the Chinese economy began to expand, orders from abroad started to gradually drop off.

In the 1990s Yingko's booming growth took a major turn, and despite a lack of talented newcomers, longtimers in Yingko began working to bring together a variety of creative styles, raising the profile of their ceramics in the art world. In 1999, Yingko's old town was renovated into a commercial area, and a ceramics museum was established in the area. The old town has developed into a leisure and tourist location with a unique cultural air, which has been complemented by individual ceramics studios coming into an ascendancy. All of this has been critical in Yingko's transformation in terms of both lifestyle and ceramic artistry.

(Teng Sue-feng/tr. by Geof Aberhart)

TTSE No. 18, a tea cultivar sometimes known as "red jade," is the foundation of Yuchih's economic redevelopment. Tea farmers belonging to the local production and marketing group produce an exquisite black tea called Forest Black Tea made from only the tenderest flushes.

Bamboo charcoal has infrared properties and also releases anions. The Ministry of Economic Affairs also erected a bamboo-charcoal display case at the Bamboo Charcoal Carnival held at the Taipei Zoo, which allowed children to experience for themselves how bamboo charcoal conducts electricity.

TTSE No. 18, a tea cultivar sometimes known as "red jade," is the foundation of Yuchih's economic redevelopment. Tea farmers belonging to the local production and marketing group produce an exquisite black tea called Forest Black Tea made from only the tenderest flushes.

Tai-Hwa Pottery provides artists with the latitude to experiment with new looks for ceramics. The photo shows the work of Cheng Shan-hsi.