Protecting Taiwan’s

Stone Fish Weirs

Esther Tseng / photos Lee Ming-ju / tr. by Phil Newell

October 2025

There are many facets to Taiwan’s stone fish weirs, including traditional fishing techniques, cultural heritage, ecological conservation, community engagement, and international interactions. They are models of sustainable development in Taiwanese fishing communities.

There are 609 stone fish weirs in Penghu County alone, their dikes extending over 133 kilometers. In particular, Jibei Island has 101 existing fish weirs, giving it the highest concentration of such structures in the world.

Groups of fish weirs that date back over 300 years in places like Penghu and the Xinwu District of Taoyuan are also remarkable for their wide variety of shapes and the integrity of historical documentation. They have earned the nickname “living fossils of fishing civilization.”

Thanks to the efforts of their owners and local cultural workers, these old fish weirs have been opened to experiential activities in an effort to pass along concepts of marine sustainability.

Lee Ming-ju, a professor in the Department of Tourism and Leisure at National Penghu University of Science and Technology, notes that most tidal fish weirs are in remote locations and were previously little studied or valued. But the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021‡2030), announced by the UN in 2017 and coordinated by the UN’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, includes a project titled “Safeguarding the Underwater Cultural Heritage of Stone Tidal Weirs on the Earth.” In this project, stone fish weirs are considered “underwater cultural heritage” and have gained international attention, with more and more weir sites being discovered worldwide.

Living fossils

The overwhelming majority of stone fish weirs around the world have fallen into disuse and are now studied mainly by archaeologists.

But things are different in Taiwan. “Even today there are people maintaining tidal fish weirs, using them to trap fish, studying them, and developing them into tourist attractions. This is very rare.” Lee suggests that in Taiwan the weirs can be called “living fossils of fishing civilization.”

Lee, who began researching stone fish weirs in 2004, says that there are three natural prerequisites to building them. First, there must be an intertidal zone with a sufficient tidal range (the difference in water level between high and low tides). Second, there must be migratory fish species. And third, there must be material to build the dikes. In Penghu this is mainly basalt and coral reef rock, while in Taiwan proper it is mostly cobblestone.

There must also be manpower to build and manage the weirs and to teach the building and fishing techniques to others, thus completing the industrial value chain.

In the seas to the north of Niaoyu (Bird Island) in Penghu County, there are stone fish weirs which can only be reached by boat. Because of differences in topography, tides, and currents, there are a wide variety of stone tidal weirs. Xinqiao Weir.

Jiuxin Weir.

Waixin Weir.

Abundant documentation

In 2012 Lee Ming-ju used a geographic information system together with historical documents to conduct a survey that found 609 stone fish weirs in Penghu. From 2019 to 2024 his student Jerry Tseng did a survey using drones, and discovered 654 weirs including relics. Of these, 101 (comprising over 30 kilometers of dikes) were found on Jibei Island. Considering that the island has only 13 kilometers of coastline, this is the highest concentration of stone fish weirs in the world.

“Can you imagine? The Penghu archipelago has only 360 kilometers of coastline, but more than 600 fish weirs, forming a ‘marine Great Wall’ 133 kilometers long. But this isn’t a Great Wall ordered built by an emperor for political reasons, but one built by fishermen to make a living,” Lee remarks.

There are many Qing-Dynasty official records of fish weirs in Taiwan, starting from 1696 and mainly related to taxation. These provide researchers with source material for their work.

In 1913, during the era of Japanese rule (1895‡1945), the colonial regime made a survey of stone fish weirs for management and tax purposes. In 1942, a survey of the fisheries industry in Penghu recorded 400‡500 stone weirs. That survey report is today held in the Yonghe branch of the National Central Library.

Fisherfolk on Jibei Island catch fish in a tidal fish weir.

Owners of a stone fish weir on Jibei Island work together to maintain the structure.

Evidence from an 1849 Pescadores map

However, the strongest evidence of Taiwan’s historically important fish weirs to show to the international community is a nautical chart made around 1849, titled “Pescadore Islands surveyed by Admiral R. Collinson, Royal Navy.” The Pescadores Islands is an old name for Penghu used by foreigners. The chart includes 66 stone fish weirs.

“We wrote to the UK Hydrographic Office to ask for an image file of the original chart, and we used the Aerial Survey for Agriculture and Forestry [which includes fisheries data], as well as microfilm, to compare the British chart to documents from the Qing and Japanese eras to confirm the accuracy of the chart.” Lee explains. For this project they enlisted the help of geographic information systems expert Chen Chao-yuan. They discovered that there were only slight differences between the 66 weirs identified on the 1899 chart (based on surveys made around 1844) and the 72 recorded in the annals of the Qing-Dynasty authorities in Penghu in 1894.

Lee says the British chart records seven weirs on Jibei Island, of which five can still be found today. Intriguingly, there is a square symbol on the adjacent Guoyu Islet that has been discovered to be a fish weir workshop. This “Pescadores” chart provides important international evidence for Penghu’s fish weir tradition.

Lee Ming-ju, who has been studying stone fish weirs for 20 years, argues that Taiwan leads the world in the preservation and transmission of stone fish weir culture. (photo by Kent Chuang)

History of Penghu fish weirs

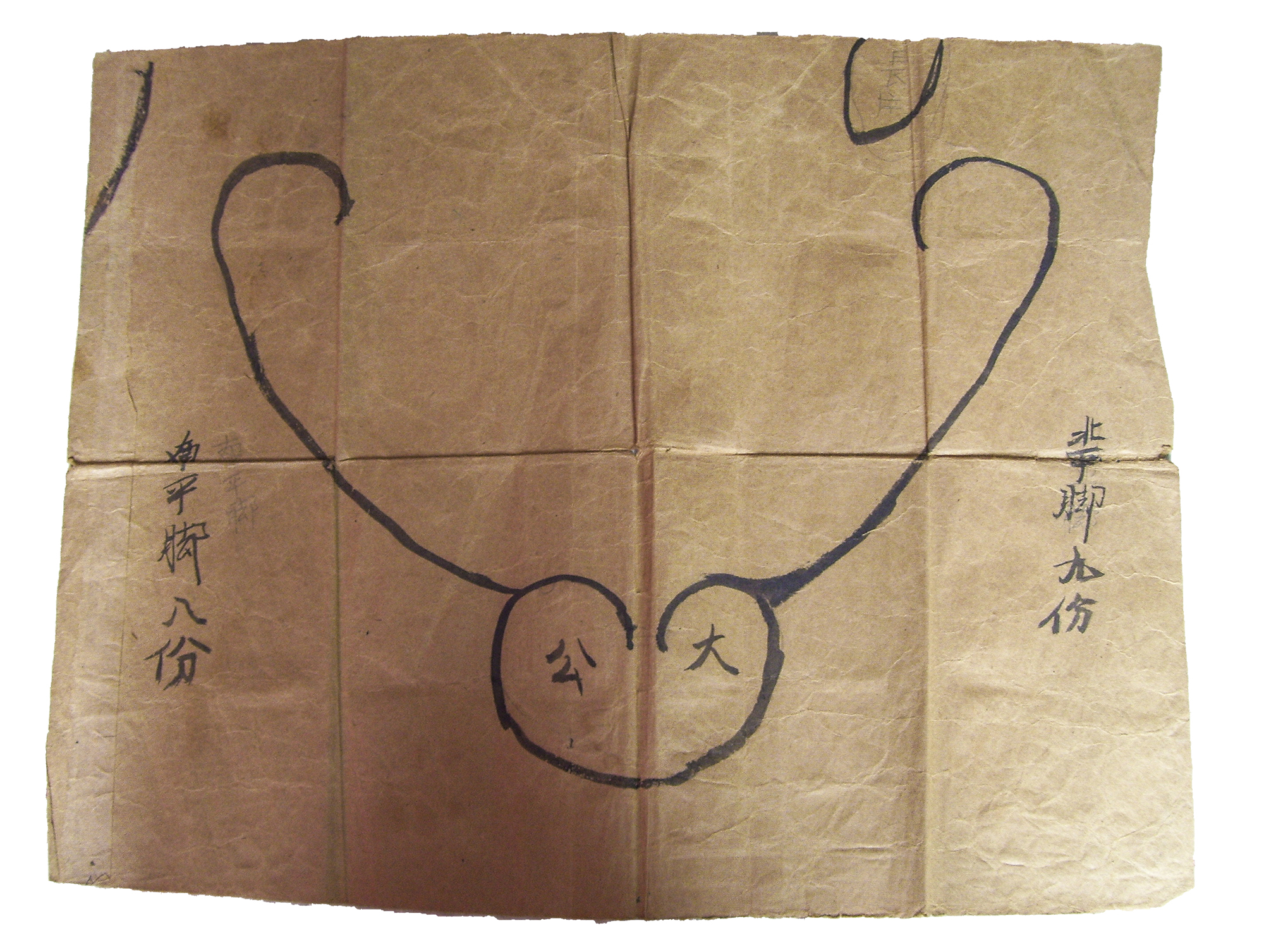

In the past, because tidal fish weirs had great economic value, shares in them could be traded, given in dowries, inherited, mortgaged, or used as collateral for loans. These legal instruments had the same significance as usage rights in real estate.

Lee says that during the Qianlong reign (1736‡1796) of the Qing Dynasty there was a lawsuit filed by someone whose weir was being robbed of fish, and the official solution was to put up a stone tablet beside the weir warning people not to steal fish there. Lee says that this tablet still exists, though it was moved to Wusheng Temple on Jibei Island when the lighthouse was built.

There was also a case involving some British citizens. During the Qing era, a British vessel ran aground in Penghu. To thank the people of Jibei for their rescue assistance, the British donated 2,000 yuan to the local government, which used the money to build two state-owned stone fish weirs.

This private document, preserved by Lee Ming-ju, indicates management roles for shareholders in a stone fish weir in Penghu.

A concave fish weir off Jibei Island in Penghu’s Baisha Township.

When inspecting fish weirs, people may carry a net to catch smaller-sized fish along the way.

Tiger Eye Stone Weir

During the Japanese era, a businessman named Lu Xian who had operated a pharmaceuticals factory in Tainan retired to Penghu and lived in today’s Xiyu Township. There he built a fish weir at Xiaochijiao that is now known as the Tiger Eye Stone Weir. His mother remarked: “Building this weir is like finding treasure at sea!” Her comment illustrates the economic value of fish weirs back in the day.

Although fish weirs are no longer used much to catch fish, their unique history and culture include wisdom about sustainability. Not only is there abundant documentation for the study of stone fish weirs, there are weir craftsman to pass down the old skills and also young people who have joined in the work of preserving fish weir culture. Even government agencies have introduced these sites into tourism itineraries. One could say that Taiwan leads the world in the perpetuation of stone fish weir culture.

A fish weir off Jibei Island in Penghu’s Baisha Township. Tidal fish weirs often have a heart-shaped pound and two long arms that may be straight or curved, depending on local tides, currents, and topography.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)