Active Aging

The Way to a Joyful Old Age

Chang Chiung-fang / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Scott Williams

September 2013

Aging populations are a global phenomenon. The march of the Baby Boomer generation into senior citizenship is giving rise to what some are calling the “silver tsunami” and bringing a tidal wave of change to national populations.

According to the Council for Economic Planning and Development, Taiwan had the 48th most aged society in the world in 2011, but is on track to become the world’s most aged, surpassing even Japan, in the next 22 years.

Faced with the rising tide of agedness, nations the world over are taking action to reduce the costs of caring for their elderly. The World Health Organization in particular was quick to spot the trend, and proposed its “active aging” program in 2002.

What does active aging do to mitigate the aging crisis?

Ping Qingyun has been living alone in her 100-square-meter apartment since her spouse passed away eight years ago. “My youngest son is very dutiful,” says Ping, a mother of six. “He lives nearby and often comes by to spend time with me.”

An 87-year-old retired elementary school teacher with a lifetime pension, Ping has no financial worries. Still healthy and mobile, she lives an orderly life, and even continues to do her own washing and ironing. She also exercises and practices yuanji dance every morning in nearby Youth Park, helps prepare communal meals at her church, and gets together with friends to play mahjong and sing.

Ping even helps out other seniors in the neighborhood by buying groceries and daily necessities for those who live alone and have trouble getting around, or simply chatting with them about the old days to ease some of their loneliness.

Music and dance add spice to seniors’ lives. The photo above shows the Forever Young String Band, part of the New Taipei City Association of Retired Persons. Below, a holiday folk music event in Beipu, Hsinchu County.

Currently, some 11% of Taiwan’s population is 65 years of age or older. But we are aging rapidly and are forecast to cross the 14% threshold for an “aged society” in 2017.

Although an estimated 10% of Taiwan’s 2.6 million elderly suffer some form of disability, the other 90% are healthy, mobile and capable of taking care of themselves.

In the past, senior support groups, both governmental and charitable, tended to focus their efforts on caring for disabled seniors and largely ignored the needs of the much greater numbers of healthy elderly. That’s begun to change as organizations have come to recognize that the old saw about an ounce of prevention being worth a pound of cure applies to senior care as well.

Over the last decade Europe and the Americas have shifted their eldercare policies to focus on support for active aging, that is, maximizing seniors’ opportunities for health, participation in society, and security.

But how do we age actively?

Lin Wan-I, a professor in National Taiwan University’s Department of Social Work, explains that the three pillars of active aging are health, participation and security.

“Participation is a key component of the active aging discussions within the European Union.” Lin says that its core tenets are keeping people active and productive in their later years through activities such as work, volunteering, education, and training.

The experience of Japan, the world’s most aged nation since 2000, offers food for thought.

Japan has been subsidizing the establishment of local “silver human resources centers” since 1980. These centers encourage seniors to take part-time work in their communities tidying parks, gardening, tending parking lots, doing carpentry, greeting guests, and translating. The work provides the elderly with a little pocket money, while also helping to reduce their healthcare costs.

Wu Yu-chin, secretary-general of the Federation for the Welfare of the Elderly, notes that the healthcare costs of the 780,000 members of Japan’s 1,597 silver human resources centers average about ¥220,000 per year (roughly NT$66,000), or about one-third of the ¥640,000 (roughly NT$192,000) per annum average for all seniors.

However, putting retired Taiwanese seniors back to work requires first changing the deep-rooted notion that seniors who hold jobs are stealing the livelihoods of young people.

According to a survey by the Ministry of the Interior, roughly 200,000 individuals over the age of 65 held jobs in 2009, accounting for 11.17% of the workforce. Of these, 51.3% worked in farming, forestry, aquaculture, or animal husbandry, 14.8% in the service sector, and 11.2% in unskilled labor.

Figures from the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics put Taiwanese seniors’ labor participation rate in 2012 at 8.1%, well below that of Korea (30.6%), Japan (19.9%) and Singapore (17.6%).

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Can seniors continue to work? Should they? The answers aren’t simply a matter of personal preference. After all, changes to the age profile of the population have a major impact on corporate operations and government resource allocation.

Nowadays, average life expectancies in Taiwan stand at 76 years for men and 83 years for women, but Taiwanese leave the workforce at an average age of 57. This gap raises two important questions: what are individuals to do with their remaining 20-plus years of life? How can our society put those valuable human resources to use?

Noting the rapid growth in the number of seniors and the rapid shrinkage in that of young people, renowned US management consultant Peter Drucker, who himself lived to the age of 95, made a prediction in his 2002 book Managing in the Next Society that people in the future would work to the age of 75, health permitting. Drucker argued further that delaying retirement was the only way the working population would be able to bear the increasing burden of retirement pensions.

In Taiwan, those seniors with jobs seem to be holding on to them.

Day Sheng-tong, the one-time “king” of Taiwan’s hat-making industry and a former chairman of the National Association of Small and Medium Enterprises, is still involved with his second career at the age of 68.

Former legislator Shen Fu-hsiung still works every day, too. He used to play the stock market in the morning and record a television program offering political commentary in the afternoon. Though he stopped playing the market two years ago to avoid the associated mood swings, he still exercises his mind developing advice on reforms to the National Health Insurance program and the Labor Insurance annuity scheme.

Corporate executives and entrepreneurs aside, do ordinary seniors have what it takes to keep working?

“Active aging begins in your 40s and 50s,” argues NTU’s Lin Wan-I. He notes that “grandmotherly” flight attendants are common on European and American airlines, that one-third of Taiwan’s laborers are 45–64 years old, and that this figure will soon exceed 40%. On the other hand, we go into physical decline as we age. “Our work environments should evolve correspondingly.”

“It’s important that employment for the aged involve opening up new opportunities, not displacing other workers.” Lin suggests that we could transition the elderly into some kind of community work or part-time positions.

As Drucker frames it, the workers of the past treated jobs as a means to earning a living, whereas workers in today’s knowledge economy see their jobs as a way of life.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Volunteering is another option for active senior participation in society.

A study that Lin published in 2008 shows that 40 and 50-year olds accounted for the largest segment of Taiwan’s volunteers, followed by 30 and 40 year olds. Seniors accounted for just 11.5% of the total, versus 30% in Sweden and 24.8% in the US.

In an effort to increase participation, the Hondao Senior Citizens’ Welfare Foundation has been operating a “volunteer hours bank” since 1998. This bank encourages individuals to contribute their labor and skills to society through a mechanism it calls the “time dollar.” Individuals accumulate “time dollars” by helping others, and then “withdraw” them when they themselves need help.

Though the “volunteer hours bank” has roughly 1,800 active volunteers, only 10% are seniors. Lin investigated the low participation rate of seniors, and found a couple of problems. The first was that many senior citizens had trouble getting around due to difficulties with the transportation system and environmental obstacles. The second was that many who were interested in participating didn’t know what they could contribute.

A 2012 Hondao survey on how seniors get from place to place found that 30% use motorcycles, 22% walk, and 10% drive cars. Only 8% rely on public transportation.

Hondao CEO Doris Lin says that getting seniors out of their homes to participate more actively in society will require making the public transportation system more convenient and improving the environment through measures such as the construction of safer footpaths.

Seniors can be remarkably vital, a fact readily apparent in their passion to learn.

Among the participants in New Taipei City’s senior education program was 102-year-old Liu Penghua, who had enrolled in an oral history course at the age of 99. His goal was to learn how to tell people his life story, including his move to Taiwan from mainland China with the Nationalist government, but he also ended up making a number of new friends.

Some seniors choose to focus on serving others. Gray-haired volunteers can often be found helping out at hospital and church events, and at recycling centers. The photos show Tzu Chi and Hsing Tian Kong volunteers.

The ultimate goal of active aging is to keep the elderly mentally and physically healthy to minimize the time they spend incapacitated by illness.

Hondao’s Doris Lin says that Taiwan’s elderly suffer some form of disability for an average of 7.3 years of their lives (6.4 years for men, 8.2 years for women). Actively promoting better health is the only way to reduce this burden.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (formerly the Department of Health) initiated a program aimed at promoting good health among the elderly some years ago. Under it, public health centers work with clinics and hospitals to educate seniors about a variety of health-related topics, including health maintenance and dietary, oral, and psychological health.

Lin argues that such healthcare promotion must be both practical and direct. Finland, for example, promotes better health by using its community centers to train the elderly in how to avoid falls, maintain cardiopulmonary fitness, and eat a healthy diet.

The 18-year-old Hondao Foundation has similarly been organizing activities aimed squarely at promoting active aging for several years.

In 2007, for example, the foundation arranged a week-long motorcycle trip around Taiwan for 17 seniors averaging 81 years of age. Hondao has continued its efforts to spread the “young at heart” spirit in the years since then, and has now sponsored an event aimed at making seniors’ dreams come true for four years running.

Music and dance add spice to seniors’ lives. The photo above shows the Forever Young String Band, part of the New Taipei City Association of Retired Persons. Below, a holiday folk music event in Beipu, Hsinchu County.

Seniors hoping for security and peace of mind in their waning years must be sure to set aside plenty of “capital.”

A 2005 Ministry of the Interior survey on the living arrangements of seniors found that 22.49% of Taiwan’s elderly lived with one of their children and 13.66% lived alone. By 2009, these figures had changed significantly, with 29.83% living with their children (+7.34 percentage points) and 9.1% living alone (-4.5 percentage points). Clearly, strong family ties remain among a senior citizen’s greatest blessings.

But the trend to having fewer children is well established and will have consequences. While 78.55% of today’s seniors have three or more children, people currently in their 30s are likely to have only one. This circumstance means that the proportion of seniors living with a spouse (the figure was 18.7% in 2009) or on their own is likely to soar when today’s 30-year-olds reach old age.

“The future will be the era of living alone,” says Lin. Having a senior center in each of Taiwan’s 7,835 administrative neighborhoods would go a long way towards improving those seniors’ quality of life, but Lin notes that we currently have only 1,700 such senior centers.

On the economic front, the MOI found that 42% of Taiwan’s seniors have their living expenses paid primarily by their children, 28.73% subsist on pensions or endowment insurance, 17.12% rely on government assistance, and 6.99% work.

When asked whether they had enough money to cover routine expenses, 63.5% of seniors responded that they had enough to get by, 21.9% that they didn’t have enough, and 13% that they had plenty.

It is important to note that Taiwan’s public doesn’t expect the government to bear all of the costs of its old age. The Academia Sinica’s 2008 Taiwan Social Change Survey found that most people thought that the government and individuals (and their families) should each bear half the cost, both of medical care and of living expenses.

There’s no single answer to how much financial capital each of us will need in our later years, but all of us can, at the very least, acquire and set aside the necessary psychological capital.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Author Chien Chen, herself now in her 50s, published Who’ll Be Waiting When You’re Gray? early this year. The book grew out of the preparations Chien began making for her own old age after losing several people dear to her in a two-year span. That experience made her painfully aware of the suffering that accompanies aging and illness. In her book, she reminds people just entering their later years that they need to make hay while the sun shines. In addition to money, that means adding to their “happiness capital.” As an example, she notes that the elderly often aren’t aware of how much they grumble and complain. “Happiness capital is like a rope wrapped around your waist,” she writes. “If you should happen to fall into despair, that rope will enable you to pull yourself back up. The elderly have to be able to depend on themselves.”

Building on the enthusiastic response to Go Grandriders, a documentary film chronicling the Hondao-sponsored motorcycle journey around Taiwan, the foundation now plans to advocate for “old age preparedness” in an effort to encourage people to embrace old age rather than fear it.

During working hours, Sweden’s department stores display the kind of merchandise senior citizens are interested in. Once rush hour is over, its bus drivers make a point of braking more gently and otherwise attending to the needs of the elderly.

The social atmosphere is changing Taiwan as well. But the silver tsunami is roaring ever closer. If we’re to stand fast, we’re going to need to be better prepared.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Music and dance add spice to seniors’ lives. The photo above shows the Forever Young String Band, part of the New Taipei City Association of Retired Persons. Below, a holiday folk music event in Beipu, Hsinchu County.

The Nan-Yang Charity Institute of Elders in Luodong, Yilan County, is a tireless proponent of education for the elderly. The seniors in the photo are learning to use tablet computers as effortlessly as their grandchildren.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

Advancing into our later years means embarking on a new kind of life, one in which we can choose to delight in our grandchildren and other pastimes, or simply take it easy.

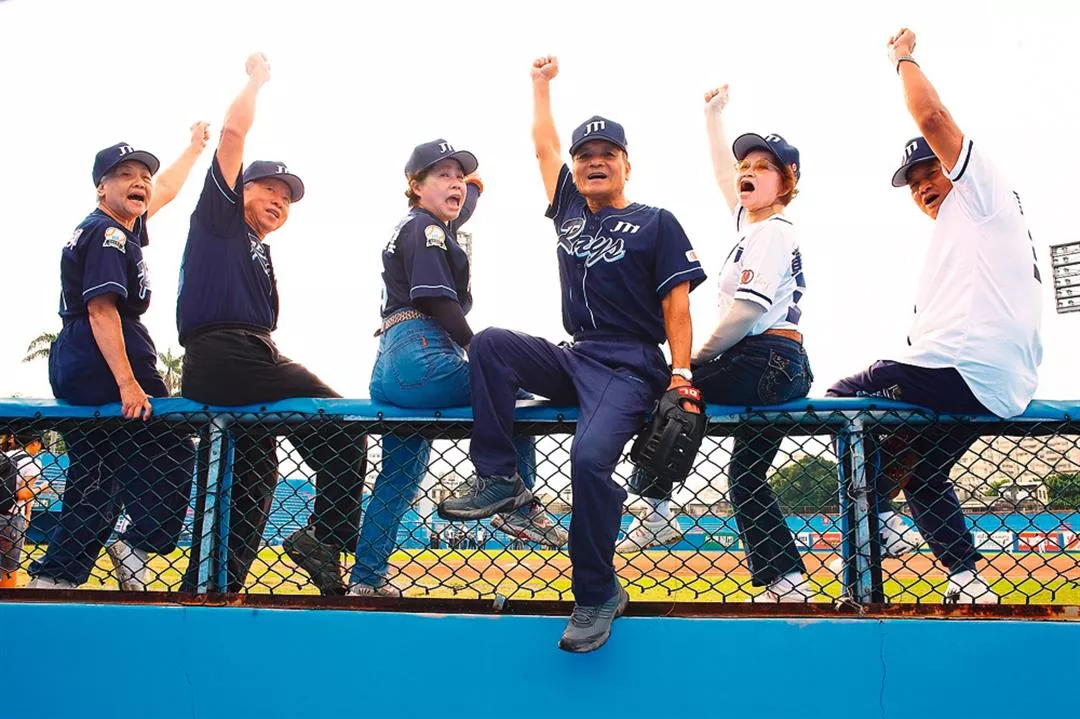

People of all ages have dreams and fulfilling them is a great way to stave off old age. The photo shows the Hondao Senior Citizens’ Welfare Foundation’s young-at-heart baseball team.

Some seniors choose to focus on serving others. Gray-haired volunteers can often be found helping out at hospital and church events, and at recycling centers. The photos show Tzu Chi and Hsing Tian Kong volunteers.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)