Charting the Aesthetic Map of Taiwan

Tsai Wen-ting / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Paul Frank

October 2004

We live in an era of aesthetic sensibil-ity. The cultural economy and creative industries hold sway, and aesthetic sensibility has become a key determinant in individual, business, and national achievement.

In Taiwan, we are blessed with majestic mountains and canyons and lovely winding rivers. We have a multicultural immigrant society, our arts and crafts display consummate skill, and our designers regularly win international prizes. We also have the world's highest density of tutorial schools specializing in the arts.

But step out of the august sphere of art galleries and take a good look at Taiwan's public spaces, where anything goes. As far as the eye can see, you will find row upon row of multistory buildings competing for uniqueness. Wherever you look, your aesthetic sensibilities will be offended. Art galleries and public spaces are worlds apart.

No matter how elegantly people's homes may be decorated, as soon as they step outside, they are like small boats in a sea of jumbled and unsightly buildings. There is no connection between people and the urban space.

Aesthetic sensibility is not just about "aesthetics" or the visual arts. It involves the feelings evoked by the five senses in everyday life. When people expect to live in a beautiful environment, they are exercising their aesthetic sensibility.

How would one go about drawing up a blueprint for an aesthetic society, given that such a project would fall under the bailiwick of no government agency but would affect every aspect of life? Where would you start building or renovating?

The aesthetic era is upon us! Following on the widespread recognition that emotional intelligence (EQ) is just as important as IQ, aesthetic intelligence (AQ) is coming to be seen as another essential competence.

Career.com CEO Weng Ching-yu, who is well acquainted with labor market trends, says that many large companies that want to hire senior executives interview them in Japanese kaiseki restaurants or French restaurants. The reason is that they consider such restaurants to be ideal places to observe a job candidate's aesthetic self-control and sense of good taste.

What's true of people is also true of merchandise. In this age of ever-diminishing profit margins, the IT industry, whose strength was for a long time limited to outsourcing, has now begun attaching importance to design aesthetics and to developing its own brands to compete in the market. Even ubiquitous real estate advertisements are beginning to attach economic value to aesthetics.

Liou Wei-gong, associate professor at Soochow University's sociology department, says, "In this aesthetic era, aesthetic sensibility is no longer an abstract spiritual concept, nor is it the prerogative of a small minority. Aesthetic sensibility is an important skill in the professional and personal life of contemporary people, and what's more, it's what society expects from us."

In the past, aesthetic sensibility was usually restricted to the visual or fine arts, and art was enjoyed and revered in art galleries, concert halls, and museums. People would dress up to enter these hallowed places, and maintain respectful silence and decorum there. By their deliberate design and ambience, galleries, concert halls, and museums were meant to make people feel that art and ordinary life belonged to separate spheres.

At the end of the 19th century, while most artists continued to create pure art, many French artists also began to integrate aesthetics into the Industrial Revolution. They made cups and furniture, and some even created exquisite cast-iron designs in Metro stations which were in no way aesthetically inferior to traditional works of art.

Taiwan, on the other hand, has many artists, but few people capable of designing beautiful metal window grilles. In Taiwan, most such window grilles are imported. There is a huge divide between artistic creation and everyday life.

In the post-modern era, art has begun to come out of art galleries and museums. Works of art are now exhibited in office buildings, shop windows, coffee shops, bookstores, and ruined buildings. The mutual admiration society that was contemporary art has now become part of life. Even the most ordinary public spaces, such as business offices and dentists' offices, have become places where people can experience beauty. "Art imitates life, life imitates art," is no longer a platitude. Public spaces have ecomeimportantvenues for experiencing artistic beauty.

Go into an Eslite bookstore in Taiwan, browse along the sprawling bookshelves,rdwood floors, and artistically appointed open spaces, and you will immediately feel at ease in surroundings reminiscent of an art gallery. Artistic appreciation is no longer a rare thing. All of society has become a wall-less art gallery.

Everyone loves flowers and greenery. A society that appreciates beauty is an eternal human aspiration.

Lost in pursuit

Liou Wei-gong says, "In contemporary society even products are talysts of sorts that stimulate people's aesthetic nerve." He thinks that these days shopping, leisure pursuits, work, and entertainment all involve aesthetic judgments.

This raises the question whether in this age of aesthetics, when faced with a wider ariety of competing aesthetic concepts and products than anyone could possibly assimilate, we are capable of making our own aesthetic judgments. We have abandoned simple but elegant red brick and black tiles, and begun importing all sorts of expensive building materials from around the world, regardless of whether they suit Taiwan.

Chiang Hsun notes that "beauty is a clear choice regarding your own life values." Every society has its own traditional aesthetic values, but in modern capitalist society these values are destroyed. Sun Ta-chuan, director of the Graduate Institute of Development for Indigenous Peoples at National Dong Hwa University, says that "as people pursue wealth, they even put a monetary value on beauty."

Sun believes that in capitalist societies, people have long been made to accept a value system that extols overwork. Hard work and thrift are regarded as paramount goals, and life has been reduced to the rat race. During the days of rapid economic growth, the government even promoted slogans such as "the living room is the factory." All of society works at a frenetic pace, and people are no longer their own masters. Sun says, "Taiwan has already entered the post-industrial age. We ought to be able to slow down. After all, leisure is the wellspring of civilization."

Hsu Fen-yu, a freelance writer who married an Italian and went to live in Italy ten years ago, has strong feelings about this: "In building an aesthetic society the most important thing is your frame of mind." When she came back to Taiwan to visit her parents, she found that Taiwanese dining rooms are elegantly appointed down to the tableware, but people rush their meals. Although they spend a lot of money on food, they don't take the time to savor it. Hsu laments that even restaurants serve their customers on a rushed schedule.

A big gate with a big smile makes everybody smile.

Culture of convenience

When making money becomes the highest value, aesthetic pursuits become a luxury that is not only discouraged but not even taken into consideration. Safety barriers around building sites are always painted in the same dull patterns. Construction companies think it doesn't matter because it's only temporary, and passersby don't seem to mind either. This clearly illustrates Taiwan's deep-rooted immigrant culture, which cares only about expedience. Chen Chi-nan, head of the Council for Cultural Affairs, shakes his head in wonder, "It's very strange. Do the Taiwanese have a particularly high tolerance for visual pollution?"

If you take a stroll through an old European city, you will also see plenty of construction going on, but buildings under renovation are covered with protective nets and with paintings of ancient monuments or of how the buildings will look once they are renovated. The aim is to make passersby look forward to the work being completed. Hsu Fen-yu says, "To most Italians, whether an object or building is beautiful is the most important consideration."

How do we go about building a society that values aesthetics? Chen Huai-en of the Department of Visual Communication Design at National Yunlin University of Science thinks that our aesthetic sensibility is still influenced by our rural past, and we have a scant aesthetic conception of foreign societies. He says that despite our hideous surroundings, a fair number of Taiwanese have developed a critical consciousness and are looking forward to an aesthetic society.

Fulfilling our shared hope will require a two-pronged approach of improving the urban environment and providing an aesthetic education. Each is equally important.

"By the water, bursting with green," Ilan's Chinshui Park lets visitors enjoy nature and companionship in a bright, beautiful setting. This is the true essence of aesthetics.

Environmental education

Hsu Fen-yu says, "In Italy, I saw hardly any tuition schools that teach artistic pursuits, but children are surrounded by beauty from the time they are born." Cities, residential houses, shopping areas, and even the stands in vegetable markets are decorated to look like paintings brimming over with vigor and vitality.

In Taiwan, on the other hand, large billboards advertising condoms with vulgar slogans can be seen in front of railway stations, and right next to ancient temples there are rows of street peddlers selling their wares in stalls made of cheap metal and plastic.

Lin Chien-ling, director of the Children's Art Museum, laments, "Improving the environment is of paramount importance, and nature is the best education in aesthetic appreciation. But in the pursuit of money and economic progress, we are willing to destroy the environment." For example, until a few years ago the hillsides around Tienmu, the northern suburb of Taipei City where the Children's Art Museum is located, were studded with Western-style buildings that gave the area a European atmosphere that Lin found very charming. Today, though, the area bristles with tall apartment blocks, and she wonders, "Do the people of Tienmu still know that their neighborhood was once a typical hillside town?"

Concerned parents who are persuaded of the importance of appreciating beauty yet find no sign of it in their surroundings, see no alternative but to send their children to extension schools that teach the arts. Lin Chien-ling, who runs 19 such schools, says, "Heaven knows, arts teachers are just teaching what children should see all around them." How can two hours a week in a cram school make up for the ugliness kids soak up everyday from their surroundings?

Lin looks at our cities with an artist's eye, and comments, "The most civilized and the most backward societies have an aesthetic sensibility, but overindustrialized Taiwan has lost its beauty. Throughout Taiwan cities look alike, and what's worse is that no city or town has a harmonious theme." The quality of building materials, the increased use of metal, cement, and plastic, and the uninspired colors, all make for a disorderly urban environment. No attempt is made to achieve a harmonious unity. Even on the drawing board, every building competes with every other building for attention. The root of the problem, he says, is that there is no attempt to achieve any harmony in urban planning.

Yu Chao-ching, professor of architecture at Chung Yuan Christian University, says, "The Chinese tradition took a very subtle and holistic approach to things. Chinese people used to stress the harmonic relationship between the human body and nature, and the microcosm and the universe. This has all been lost."

Public spaces where we can stop and linger become part of our lives. Pictured here is the Huashan Art District in Taipei City.

History

"Our society is obsessed with innovation and style," says Yu Chao-ching: old buildings are continuously pulled down and new "creations" erected in their place, time and again upsetting the old sense of harmony. To put a positive gloss on things one might say that Taiwan's cities are a laboratory of architectural style, or an architectural patchwork quilt-but in fact, they are a blindly cobbled-together mess, lacking any sense of autonomy.

Lin Po-nien, editor-in-chief of Space magazine, wonders, "Is the aesthetic goal of reconciling change and architectural harmony that difficult to achieve?" Our architects compete with each other to design unique buildings, but do they consider whether the buildings have a harmonious relationship with their neighborhood and its history? Or do they just see their buildings as individual works of art-the more creative the better?

Yu Chao-ching says that aesthetic sensibility is not just an individual quality. The reason Western countries treasure ancient buildings is that they represent the collective memory of a place, as well as people's link with their history. Old buildings are the soul of a city. Urban planning in Singapore, which is not that far from Taiwan, seeks to achieve a temporal and a three-dimensional effect. What makes Kyoto, Florence, and Paris so beautiful and unique is their history.

Hsu says, "Italy's old buildings are renovated continuously, and just about every home has some hundred-year-old furniture. Old things are treasured, renovated, and passed on from generation to generation."

In recent years, the idea has gained ground that vacant spaces ought to be reutilized. A case in point is the Taipei Mayor's Residence Arts Salon, a Japanese-style building on Hsuchou Road surrounded by bamboo groves. On weekdays and holidays, small groups of people sit on the salon's tatami floors and engage in conversation while drinking coffee. This historic building has not only been preserved, but it is now part of people's life.

A crowded metro station can also be a wall-less museum. Public spaces are ideal places to develop an aesthetic sensibility.

Reconciled with nature

Besides preserving a link with the past, becoming reconciled with nature also affords a feeling of harmony, and is essential to developing a genuine style.

Lin Po-nien notes, "In Taiwan you had better not be too particular about style. Our style has long been overinterpreted by artists and architects." Yu Chao-ching says, "Style ought to be an expression of your inherent character."

Sun Ta-chuan says, "Taiwan's personality resides in mountains and the sea." Sun thinks that the loss of Taiwan's aesthetic sensibility and the cause of many environmental problems is that Taiwanese people have approached this country of high mountains and the open sea with the mentality of flatlanders. He explains that in Taiwan every mountain and river is unique. For instance, the Tungshan River in Ilan County and the Ai Ho (Love River) in Kaohsiung could not be more different. If you recognize this and express yourself, you will develop your own style quite naturally.

We know Europe and America well, but have become estranged from the Pacific Basin. In Taipei you can find delicious food from all over the world, but of all the events organized recently to celebrate the city's 120th anniversary, not one was in any way related to the Tanshui River. Sun Ta-chuan laments, "The people of Taipei have completely forgotten the Tanshui River. The river banks have been hidden behind high embankments."

Public spaces are among the main locations for modern people's encounters with beauty. The public works of art shown here are a giant birdcage on Tunhuang South Rd. in Taipei.

Tungshan River

City folk tend to ignore nearby mountains and rivers, but for several years Ilan on the Lanyang Plain has been cited by the media as a prime example of a beautiful city in harmony with its natural surroundings.

Fifteen years ago, the Ilan County government hired the Japanese design firm Atelier Zoo to landscape Tungshan River. Chief designer Kuo Chung-duan told the county government that before beginning work on the project, she would need one year to observe and understand how the river is affected by the four seasons. She didn't expect the government to agree to this. After ten years of work, Chinshui Park was completed, and it changed people's attitude toward public works projects. Along with the Luotung Sports Park and the Atayal Bridge, Chinshui Park has made the people of Ilan County feel good about public works projects and given them a renewed appreciation for their natural environment.

The people of Ilan, which was long thought to be a backwater, have become more self-confident thanks to the park. Chen Chi-nan, head of the Council for Cultural Affairs, thinks that the relandscaping of Ilan is an excellent example of "critical regionalism."

Public spaces are among the main locations for modern people's encounters with beauty. The public works of art shown here are a public telephone booth in Kaohsiung.

Isolation amid plenty

Once we have established a more harmonious relationship with nature, the next step is to establish relationships with other people. Yu Chao-ching says, "The main environmental problem in Taiwan is that there is an abundance of material goods and a dearth of genuine relationships." Chen Huai-en agrees: "Our open spaces are not welcoming to people who want to stroll, hang out, or look around."

If you take a good look at most buildings and public spaces in Taiwan, you'll find that they all have an individual design, but taken together they look ugly. Every building is like an island cut off from its surroundings.

Tseng Tzu-feng, chairman of the Graduate Institute of Urban Development and Architecture at Kaohsiung University, adds, "The aesthetic quality of a public space does not spring from inert objects but rather from the interaction between people and that particular environment."

Three years ago, the Kaohsiung Cultural Center, with a surface area of 13 hectares, was surrounded by a wall nearly 450 meters long, which meant that people could only enter it through the main front and back gates. The lush wood within the enclosing wall grew bleak and desolate, as did the footpath outside the wall. Like most government offices that were protected by walls in the past, the cultural center felt intimidating and unapproachable to people.

A seemingly miraculous transformation occurred when the wall was torn down: people flocked to the green fields and wooded area, and were no longer cut off from it. Overnight, the grounds of the center became a recreational area where elderly people exercised, children rode their bicycles, and couples went for a walk.

Lin Po-nien comments, "Cities are crowded by their very nature, and because of this they need some kind of order. In former times, the emperor had the final say in how urban spaces were organized, and all buildings took the imperial palace as their yardstick. In the democratic era, citizens have formed a close relationship with public spaces, giving them a key role. Public spaces afford people the most immediate aesthetic awareness of their environment."

Advertisements compete for people's attention, but none stands out when all are cluttered together.

The leading role of public spaces

Cultural critic Nanfang Shuo argues that aesthetic sensibility is developed in two stages. The first comes with environmental improvement and economic development. A common saying goes, "not until the third generation of affluence do people know how to dine and dress." Even more important is the effort to develop one's own "human character," to be considerate and respectful towards others.

Tseng Tzu-feng says, "The biggest obstacle to an aesthetic society remains the deterioration of public spaces." Tseng tells people to conduct a little experiment: when you leave an aesthetically appealing private house, you'll soon notice that the farther away you get from it and the closer you go to a public space, the uglier everything around you will be. What you see as you cross the threshold of the house, that is to say the interface between private and public, is so miserable that you can barely bear to look at it.

In the past, people attached great importance to the front entrance and courtyard of a house, but nowadays people pile up odds and ends there. They also use their staircases to store smelly shoes. People rarely bother to do anything about rusty window bars and grimy outside walls. They also talk loudly into their cell phones in public spaces, afflicting other people with noise pollution.

In recent years, the Taipei City government has seized its takeover of the management of sewers as an opportunity to clean firebreak lanes between buildings that have been illegally occupied. The city has set up wooden frames for vine plants, planted flowering plants, and placed mosaics to turn back alleys into beautiful rear gardens.

Even so, beauty imposed from above on citizens who lack a public consciousness has a way of unraveling. When it suited them, people quickly reversed some of the changes. Tseng Tzu-feng notes, "For a public space to truly come to life, it has to spring from the community's imagination."

In one of the main lanes of the village of Wutai in the mountains of Pingtung County, there is beautiful stone-slab pattern in black, the Rukai tribe's favorite color, on a side wall. Below the wall a small electric box has been painstakingly covered with a wooden ornament. A careful look at the wall pattern reveals a couple of hundred-pace snakes guarding a ceramic pot containing lilies. The tribespeople told us the snakes symbolize friendship, and among Rukai friends protect each other. The snakes are a way of sharing an aesthetic sensibility. In cities and towns in the lowlands you don't see anything like this. All you see on big walls in the city are billboard advertisements.

Now that the aesthetic age is upon us, and people are pursuing beauty and style, can't we learn from the Rukai people and integrate beauty, ourselves, and our community, and live in harmony with our traditions and the environment? Why not make "a beautiful people in a beautiful land" our guiding principle? If you want an aesthetic society, you have to do your bit.

The Mukua River in Hualien. Boundless grasslands, magnificent mountain valleys, and beautiful rivers are the stuff that aesthetic sensibility is made of.

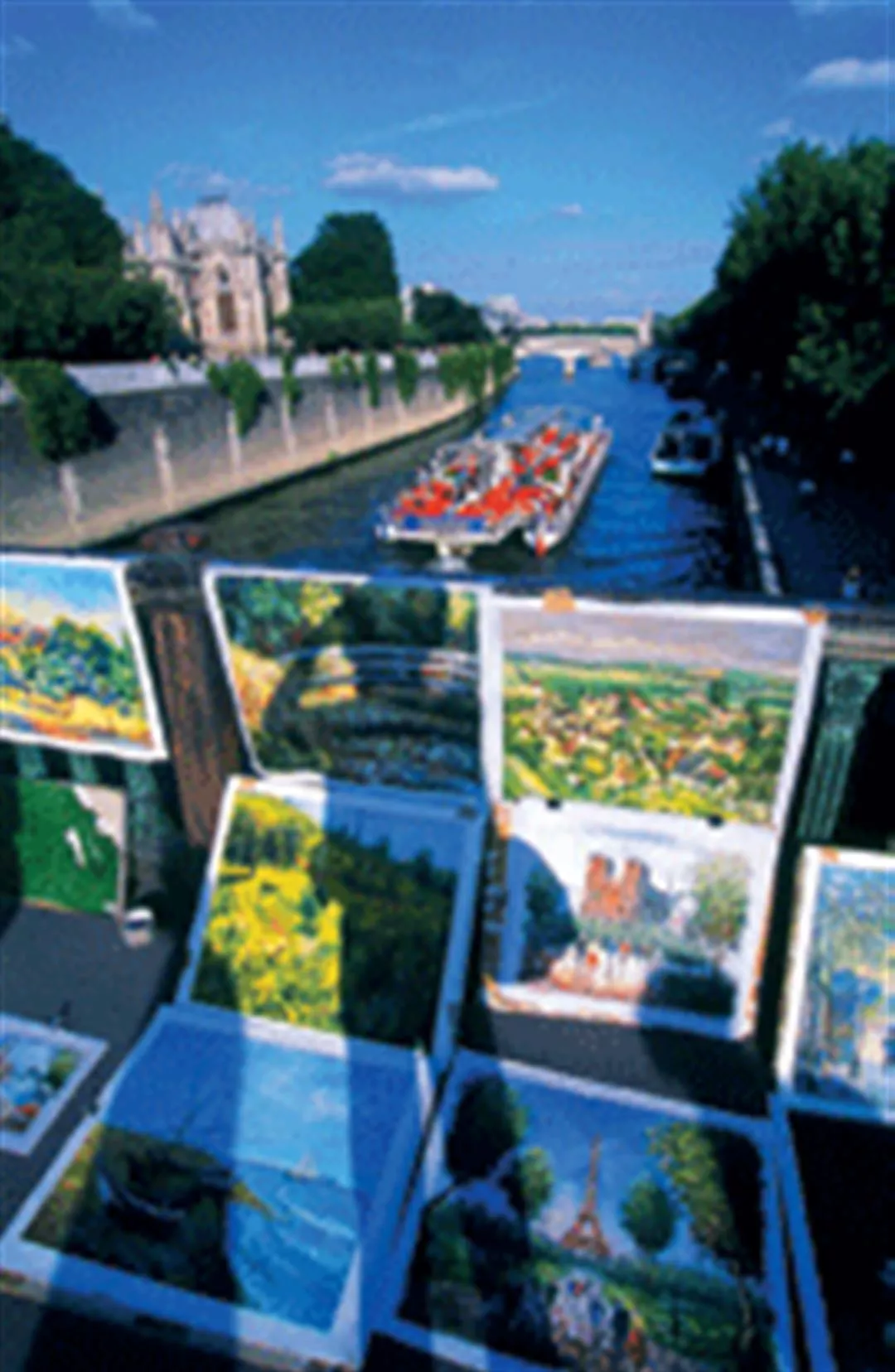

Notre Dame Cathedral stands majestically on the banks of the Seine. History is the foundation of an aesthetic society.

Art has begun to come out of art galleries and into people's lives. In the aesthetic era, art and life are not separate.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)