No Longer Hidebound:400 Years of Industrial History in Taiwan

edited by Coral Li / photos courtesy of the Government Information Office / tr. by Phil Newell

June 2003

Did you visit the recent exhibition "Ilha Formosa-The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century," staged at the National Palace Museum? It gave the public a better idea of Taiwan's glorious past, in which, even 400 years ago, Taiwan was already playing the role of an "Asia-Pacific trading center."

In the 17th century the main exports were deerskin and cane sugar; in the 19th they were tea, sugar, and camphor; in the 20th, ready-made clothing and umbrellas; and in the 21st, they are high-tech information industry products. In the span of four centuries, how has Taiwan been able to continuously play an important role in the global supply chain? How have various industries in Taiwan evolved? What glorious accomplishments have been recorded, and what disappointments encountered? What kind of industrial history has been woven as a result?

Guided by Hsieh Kuo-hsing, a researcher in the Institute of Modern History at the Academia Sinica, Sinorama readers are invited to gain a systematic understanding of the development of Taiwanese industries over the past four hundred years.

Industrial history can be explored on three levels. One is the history of a particular sector, such as food products or petrochemicals. The second is the history of a particular company or enterprise, such as National (Taiwan Panasonic) or President Enterprises. The third is the biographical history of entrepreneurs, such as the Hung family, who founded the National brand.

Of these, the third level is perhaps the most interesting. This is because business is mercurial, and enterprises that flourish in one particular phase can, in the next stage, decline as a result of changing circumstances or a different environment. Thus when studying the past the focus should be put on the entrepreneurs and their lives, not only describing the successes and failures of their ventures, but also giving due regard to the ideals they embraced and the admirable aspects of their characters.

Export Processing Zones were an invention of which Taiwanese can be proud. Brisk exports from the EPZs drove growth in satellite factories in Taiwan proper, leading to economic "take-off." The end of the working day at an EPZ became an important image from that era.

The early pioneers

Although Taiwan began developing relatively late, right from the outset its development was strongly commercially oriented. In the early 17th century, Taiwan had huge numbers of deer (especially Formosan sika), and immigrants from mainland China traded salt, iron, and daily-use commodities to Aborigines for deerskin and venison. After the Dutch brought Taiwan into the global maritime trading network, deerskin became Taiwan's first major export product. Japanese merchants also sailed to Taiwan to trade with the Aboriginal peoples during this period.

However, as result of excessive hunting, the number of Formosan sika declined dramatically by the late Qing Dynasty, and the creature was virtually extinct by the 1970s. The only remaining deer in Taiwan these days can be found either in Kenting National Park, where the government has implemented a program to conserve the Formosan sika, or on a few farms in central Taiwan, where farmers raise Formosan sambar (also deer) commercially, though for their antlers rather than their hides.

The Dutch era also saw preliminary development of agriculture in Taiwan, with the main crops being rice and sugar cane. The Dutch imported oxen from Southeast Asia, and began farming. However, cultivation techniques were rudimentary, and more advanced rice growing techniques only arrived with the large-scale immigration of people from southern China after the expulsion of the Dutch.

Cane sugar was the second-largest export commodity in the Dutch era. Its cultivation was strongly encouraged, and the plains of central and southern Taiwan were covered in cane fields. The primitive crushing technique involved the use of a stone turned by a harnessed buffalo. Although the form of power for this industry remained stuck at this crude level for centuries (the first modern sugar refinery was established only in 1900), the technique was productive enough to allow for the export of cane sugar to Japan and Europe. Rice, meanwhile, was exported mainly to mainland China.

Following the opening of ports in Taiwan to international maritime trade in the late Qing Dynasty, tea, sugar, and camphor were exported around the world. Cane sugar remained a key export right up into the 1950s and 1960s, when sugar harvesting was a common sight in southern Taiwan.

The three treasures of Taiwan

In the early years after Taiwan came under the control of the Qing Dynasty, which happened in the latter part of the 17th century, the economy depended mainly on agriculture, forestry, fishing, and animal husbandry. The immigrants then flooding into Taiwan had to bring with them even the basic implements of daily life such as pots, stoves, farming tools, and kitchen utensils.

It was during the 1860s, late in the Qing Dynasty, that Taiwan's industrial structure underwent a significant transformation. This was a result of the Treaty of Tianjin, which opened up several ports in Taiwan-including Lukang, Anping, and Tanshui-to maritime trade. When foreign merchants came to Taiwan they discovered three agricultural products highly suited for export: tea, sugar, and camphor. Through the intermediary of foreign merchants, trade in these goods-known as "the three treasures of Taiwan"-boomed, and they remained the main exports right up into the Japanese colonial era (1895-1945).

Trade in sugar and camphor was an extension of the agricultural successes achieved under the Qing. Because Taiwan's cane sugar was very sweet, it remained continually competitive in the international market. Meanwhile, Taiwan was the only place in the world besides Japan to produce camphor on a large scale. In fact, camphor was first exported early in the Qing Dynasty, though volume remained small, and it was mainly used as an herbal medicine or medicinal ingredient. It was only in 1880, with the discovery that camphor could be used as raw material for celluloid, that large amounts were exported. The earliest synthetic plastic, celluloid was widely used in daily-use items like combs and buttons. In the Japanese colonial era, Japan made camphor into a state monopoly, which became (along with the monopoly on opium) a major source of trade revenues for the government. It was only in the 1920s, with a sharp decline in the number of camphor trees, that production came to an end.

The third treasure of Taiwan-tea-though a relatively late entrant, wrote (and continues to write) a glorious page of economic history.

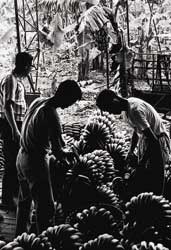

Agriculture was the mainstay of the economy in the early days after the arrival in Taiwan of the ROC government. Banana exports to Japan were especially important to the economy. The photo shows bananas being picked and crated in the early days.

Tea heads west

The earliest tea in Taiwan was wild tea growing in the mountains around Puli, Nantou County. A small number of Aborigines also cultivated tea for medicinal purposes, but because under theories of Chinese medicine it was considered "cold," it was not deemed suitable as a casual drink.

Large-scale cultivation of tea began only with the arrival in Taiwan of immigrants from Anxi (Fujian) during the Qing Dynasty. Via the Tanshui, Hsintien, and Chingmei rivers, they penetrated into Shihting and Shenkeng on the southern rim of the Taipei Basin, where the topography is similar to the Anxi region. These immigrants began to plant oolong tea here, and, through British tea merchants, "Formosa tea" was exported to Europe and America. To get a piece of the action, foreign companies set up bases in Taipei, further propelling development in northern Taiwan, which was then still largely wilderness. Later, cultivation of oolong tea spread to central Taiwan.

The oolong tea grown at that time was not the Tungting oolong tea that we know today. It was a kind of "curled" tea, a result of its being heat-dried for a longer time than modern oolong tea, so that in fact it was closer to modern black tea. Later, when tea exports stagnated for a time, tea merchants brought unprocessed tealeaves back to Fujian for further refinement. By adding jasmine and other fragrant flowers, they created a taste closer to green tea. Business boomed, and this product, known overseas as "Taiwan paochong tea," became especially popular among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.

What we know today as Tungting oolong tea could in fact be more accurately named "semi-curled" paochong tea.

Besides oolong and paochong, in the late Qing period and into the Japanese colonial era, black tea was also an important export. Because Japan itself produces green tea, to prevent competition and also to meet demand in the European market, the Japanese colonial government encouraged the growing of black tea in Taiwan. They brought Assam tea to Taiwan and began trial planting in 1920. By 1930, many large-leafed black tea trees had been planted around Sun Moon Lake, and the Mizui company selected the name Niddo for this product. It competed against Lipton in Europe, and was very well received; it continued to sell briskly right up into the 1950s. Production volume at one point reached five million kilos per year. This is a stage of history that is virtually unknown to most people in Taiwan who now imbibe imported Lipton tea.

Production of green tea in Taiwan began only in 1949, when masters of the craft from Fuzhou brought their skills to Taiwan. Most production took place from Hsinchu to the northern coast, and exports reached millions of kilos per annum. After a "golden age" of a dozen or so years, rising costs of production and peculiarities in flavor made green tea uncompetitive internationally, and it fell into decline after the 1960s.

The second spring for Taiwanese tea came in the 1980s. With Taiwan's economic takeoff, domestic demand sharply increased, and it was just at this time that Tungting oolong tea came onto the market; sales grew rapidly, albeit mainly for the domestic market. The most important tea-growing area in Taiwan today is the Chiayi belt. (Early tea-producing areas have been ruined by excessive use of chemical fertilizers. In fact, the well-known "Luku tea" is actually made by purchasing top quality tea from around Taiwan and refining it in Luku, so that what Luku really sells is its processing skills.)

With the first energy crisis hitting in the early 1970s, the government realized the importance of developing heavy industries like petrochemicals, steel, and shipbuilding. These provided the foundations for the flourishing of manufacturing in Taiwan in the 1980s.

Industry in Taiwan

The development of modern industry in Taiwan mainly began in the Japanese colonial era. In the early years of Japanese rule, under the policy of "industrial Japan, agricultural Taiwan," Japanese industrial products were sold to Taiwan, and Taiwanese agricultural products were exported to Japan. But this changed around 1931. For one thing, Taiwan's agricultural development had reached a saturation point. Moreover, in 1931 Japan occupied Manchuria, and thereafter saw Taiwan as a springboard for further advances into Southeast Asia. A new policy of "industrial Taiwan, agricultural Southeast Asia" was crafted, and Japan began to actively promote industrial development in Taiwan with an eye to making the island self-sufficient in the event of war in the Pacific.

The Japanese contribution to development can be seen in three areas. In terms of basic industry, the "new city" of Kaohsiung, which the colonial authorities began building in 1904, became the main base for moving farther into Southeast Asia. In terms of electrical power, the Japanese built the Sun Moon Lake generating station, providing the energy needed to develop industry. And in terms of irrigation, the Taoyuan and Chianan irrigation projects were completed. The latter, drawing from Shanhu Lake and the Chuoshui River, provided water to nearly 150,000 hectares of land, much more than all the Qing Dynasty irrigation projects put together.

Transportation, a critical part of infrastructure, is a relatively neglected aspect of the construction undertaken by the Japanese. This applies to both main railroads and light rail transport. Before the Japanese era, most transport up and down the coast of Taiwan was carried on by sea, with on-land travel being limited to ox-drawn carts and walking. Transportation greatly improved with the widespread construction of light rail lines by the Japanese. There were two types: Very narrow rail lines could be used by hand-powered cars, while slightly wider ones were used for the narrow-gauge trains of the Taiwan Sugar Corporation. These light rail lines, which were built not only in the plains but also in the mountains, were the main means of transportation in the early Japanese colonial era.

It was only in the 1930s, when motor vehicles became more common and more highways were constructed, that the light rail lines were removed one after another. Highway construction mainly involved widening the routes already being used by the light rail lines, and rail line operators rushed to get into the motor transport business. These entrepreneurs, using the large amounts of capital they earned from transportation, became important business people in the latter part of the Japanese colonial era.

In addition to basic industrial infrastructure, the Japanese also established several large-scale manufacturing operations, which became the forerunners of the later Taiwan Power Company, Taiwan Salt Company, Taiwan Sugar Company, and China Petroleum Corporation. After the ROC government came to Taiwan in 1949, they converted these Japanese industries into state-run corporations, many of which even now play a vital role in the economy.

Another important contribution made by the Japanese era to industrial development in Taiwan was the creation of a high-quality labor force. By 1945, the literacy rate in Taiwan had reached somewhere between 70% and 80%, meaning that when the ROC government got here, there was already a large pool of primary and mid-level industrial labor. This would prove to be very important in postwar economic construction.

One of the key next steps for Taiwan's economy will be in the direction of the smokestackless tourism and leisure industries. If these can be combined with local culture, the possibilities are limitless. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

The five big families

It was also during the Japanese occupation that the "five big families"-clans that would dominate commerce and politics in Taiwan for many years-made their fortunes. We will look at them from north to south, starting with the Yen family of Keelung, which made its money in mining. Yen Yun-nien borrowed money from friends and family to lease a small area from the Japanese for mining around Chiufen (which many people considered to be exhausted) and flourished from gold mining. At the same time, the perspicacious Yen foresaw that the expansion of Keelung Harbor would create new opportunities for the coal fuel market. Therefore he went into business with Japanese to actively develop the coalfields in northern Taiwan, where output eventually accounted for two-thirds of all coal produced on the island and the region boomed for half a century.

The second of the five big families was the Lin family of Panchiao. Lin Ping-hou, who generated the family's wealth, started out as an apprentice in a rice shop, and afterwards made his fortune in commerce. He called his company "Lin Pen-yuan" from an ancient Chinese aphorism that translates loosely as "always remembering to be grateful for favors conferred." Later, the family bought large amounts of land and grew even more prosperous from the rents, becoming the wealthiest family in all of northern Taiwan. The Lin clan produced five sons and grandsons, some of whom returned to mainland China. For example, Lin Heng-tao, the late well-known historian of Taiwan, grew up in Fujian Province. Lin Hsiung-wei, the founder of Huanan Bank, was a Lin family offspring who came back to Taiwan from the mainland. At that time Japan was planning to move into Southeast Asia, and encouraged Lin to invest in a bank; Huanan then became one of the economic pillars of Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia. Lin's most widely praised action was his creation of a scholarship fund that sent many young people from Taiwan to Japan to study, including Wu San-lien and Tu Tsung-ming, who would become influential intellectuals.

The third of the five families was the Lin family of Wufeng. Classic immigrant landowners, the Wufeng Lins became one of the richest clans in central Taiwan by developing and renting land in the early Qing Dynasty. The Lin family was also known for their belligerent and courageous nature. At that time most of the large landowning families maintained private military forces. During the Sino-French war (1883-1885), Lin Chao-tung was awarded a title as a result of his military exploits. When Liu Ming-chuan became governor of Taiwan, he sent Lin to "pacify" the Aborigines and to handle the pioneering and development of mountain land. Because of his success in these areas he was awarded a monopoly for camphor, and the family thrived even more. Lin Hsien-tang, a later descendant, was a key figure in society during the Japanese occupation era because of his anti-Japanese orientation and his efforts on behalf of cultural enlightenment in society.

Number four was the Koo family of Lukang. Koo Hsien-jung, the founder of the family fortune, was a classic dealmaker. From his welcoming of the Japanese into Taipei in 1895 to his contributions to the Japanese colonial government and to stabilizing social order, he continually maintained good relations with the colonial regime, in return for which he received monopoly privileges for camphor, edible salt, and opium. In addition, the Koos proved bold and adept at grasping trends, making investments, and diversifying their business interests, so that today, they are the only family of these original five to remain influential in industrial and commercial circles in Taiwan. The Koo's Group, one of the biggest conglomerates in Taiwan, is run by the heirs of Koo Hsien-jung.

The fifth of the five big clans was the Chen family of Kaohsiung. Chen Chung-ho, the founder of the family business, was born into a very poor family. As a young man, he went to work as an accountant in the firm of Chen Fu-chien, one of the main players in the sugar industry in southern Taiwan at that time. Chen Chung-ho was rapidly promoted because of his obvious business talents, and after Chen Fu-chien passed away, Chen Chung-ho went out on his own and became a success. During the Japanese era, he provided important services to the regime and in turn received economic privileges, and in the span of a few short years, the family became one of the wealthiest in southern Taiwan. For a time during the Russo-Japanese War, Chen's business was at risk because a sudden collapse in the price of sugar left him deep in debt, but he was able to come through this crisis and retain his position as a leader in the sugar industry. Chen Tien-mao, a member of the second generation of this family, later served as speaker of the Kaohsiung City Council.

No electricity, no industry. The Sun Moon Lake power generating station, which was built by the Japanese, played a critical role in early industrial development in Taiwan. (courtesy of Teng Hsiang-yang)

One step, one footprint

Taiwan's postwar industrial development can be divided into five phases:

(1) The US aid phase (1945-1952): Much of the industrial infrastructure created by the Japanese was badly damaged in the latter part of World War II, so the early postwar period was devoted mainly to reconstruction. In 1949 there was hyperinflation, and it became necessary to rely on US aid to develop light industry. It was in this phase that the textile industry, which would have a far-reaching impact on Taiwan's economy, got started. Using US dollars, cotton was purchased overseas and then turned into textile products to supply domestic demand.

(2) Import substitution phase (1953-1961): In this phase Taiwan began to develop light industry providing products for daily use, aiming for economic self-sufficiency. The government imposed controls on foreign exchange and restricted imports. Beginning in the 1950s, leading business figures from the prewar "Shanghai Gang" and "Shandong Gang" came to Taiwan, where they contributed to building up the foundations of basic industries. Corporations from the Shanghai Gang that still are active today include Far Eastern and the Yue Loong Group, while Ruentex and the Mitac-Synnex Group are among those who remain from the Shandong Gang. Some native Taiwanese business groups also arose during this phase, including the "Tainan Gang," Formosa Plastics, and the Shin Kong Group.

(3) Export expansion phase (1962-1973): Export processing zones (EPZs), the brilliant idea of K.T. Li, were created in this stage, offering an excellent investment environment to attract overseas Chinese and foreign investment. Besides bringing in technology and management skills, the EPZs exported low-cost products for daily use, earning large amounts of foreign exchange. Given the fact that EPZs were linked into global industrial development, plus Taiwan's superior quality labor and hard-working population, trade boomed. This in turn drove the rise of satellite factories around Taiwan, and Taiwan's overall economy began to take off.

(4) Energy crisis phase (1974-1984): The first oil crisis struck in 1974, and the government decided to develop heavy industries, such as petrochemicals. Companies like China Steel, China Petroleum, and China Shipbuilding arose during this phase, which also witnessed the construction of naphtha crackers. The government launched the "Ten Major Projects" (large infrastructure programs) in 1976, laying the foundation for the next wave of economic growth in Taiwan.

(5) Economic liberalization phase (1985 to the present): Taiwan began to develop high-tech industries in the late 1980s and 1990s. These have become the industrial mainstream, especially the design and manufacture of computers and optical electronics.

Taiwan began to develop high-tech industries in the 1980s, laying the foundations for today's engines of growth-information products and optical electronics. (photo by Diago Chiu)

Whither SMEs?

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have played a critical role in Taiwan's economic development since World War II. Under the export orientation policy, by taking advantage of their flexibility and their skill at making improvements in the production process, SMEs accounted for 70% of the value of all exports from Taiwan up through 1986, and created the internationally renowned "economic miracle."

But given changes in the world situation, especially the rise of mainland China and other developing economies, Taiwan's SMEs have gradually lost competitiveness. In 1991 they accounted for only 50% of the total value of exports, and by 2001, this figure had fallen to 20%. Despite the fact that they are not keeping up with overall growth, over the last 20 years the number of SMEs has not changed significantly. Although many companies have gone out of business, others have arisen to take their place.

In the age of globalization, what is to become of SMEs, which still account for 98% of the total number of all enterprises? Mainland China's "magnet effect" on Taiwan appears to be irresistible, so how will Taiwan's economy develop? The government's aim to make Taiwan into an "Asia-Pacific Regional Operations Center" is praiseworthy, and Taiwan is quite well qualified for this role, but in recent years politics has hampered the economy so that while the slogan survives, progress in the areas of operations and R&D centers has been slow. This is very worrying to those in the know.

Local revival

Because development of manufacturing has reached a bottleneck, besides making Taiwan into a regional center for business operations and R&D, the next wave of economic development in Taiwan will move toward smokestackless industries, traditional industries driven by domestic demand, and tourism and leisure. Many small countries in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, such as New Zealand, offer examples of success to follow in pursuing this possibility. The government has also devoted attention to this trend in recent years. As the Ministry of Economic Affairs is working to develop industries with special local characteristics, the Council for Cultural Affairs is at the same time working from the angle of overall community development. The goal is to develop local cultural industries, and bring together local cultures, natural endowments, and local identity to create brand new industries.

The many successful examples of reconstruction following the September 21, 1999, earthquake have added new vitality to the possibility of creating industries based on local characteristics. For example, some community workers in Hsiufeng Village in Luku Rural Township started a business with only NT$500,000 in capital to repackage Luku tea leaves in an elegant and appealing way, and by playing on the heartwarming story behind the sale of the tea: paying for the continued operation of a cafeteria for local elderly people who live alone.

Also, in Chungliao Rural Township, in the heart of the disaster zone, a dozen or so middle-aged ladies have organized a workshop where they do hand-dyeing using vegetable dyes, thereby combining local culture with the spirit of environmental protection. Meanwhile, women in Tungshih have organized a cooperative to make and sell Hakka cuisine. Although all of these operate on a very small scale, they can help resolve local unemployment problems to a considerable degree. If these can be integrated with the tourism industry, so that outsiders and foreign visitors will become consumers of these goods and services, there is considerable potential for development.

After more than three centuries, what will be the face of Taiwan's industries in the next 100 years? This will be a test of the wisdom and ability of this generation of Taiwanese.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)