At a memorial ceremony after Tai- wan's devastating 21 September earthquake, President Lee Teng-hui, quoting Buddhist Master Sheng Yen, described the more than 2,300 compatriots who lost their lives as "living bodhisattvas" who had borne the brunt of the disaster for the rest of us, and whose deaths should remind us of the importance of being prepared for natural disasters. Academia Sinica president Lee Yuan-tseh said that disasters can strike at any time, and the people with the best chance of survival are always those who are best prepared.

The blood and tears have barely been wiped away, and the successive earthquakes which continue to rock Taiwan demonstrate that the danger is not past. Just what lessons have we learned? What warning should we take? And how can we prepare ourselves for the next time?

The 21 September Chichi earthquake has left an indelible scar in the collective memory of the people of Taiwan. But despite the pain, on reviewing the events many experts feel nothing but relief.

"If the earthquake had happened at ten in the morning, the number of casualties among schoolchildren would have been unimaginable." Associate Professor Chen Hui-tsu of National Central University's civil engineering department says that quite apart from the number of school buildings which collapsed, just the thought of how many children might have fallen or been trampled as they fled in terror from upper floors is enough to send a shiver down one's spine.

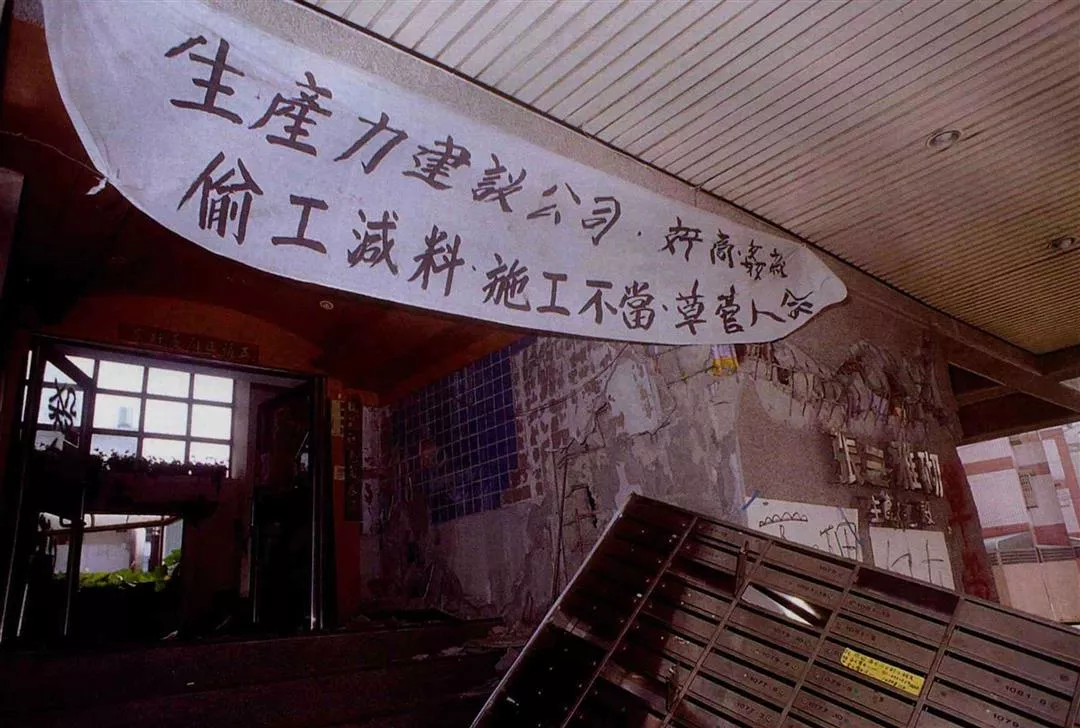

Builders, or jerry-builders? Over 20 high-rise buildings around Taiwan toppled "solo," and countless others were made unsafe. The many pernicious practices of Taiwan construction industry really do merit critical examination. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

If the epicenter had been in Taipei. . . .

The earthquake damaged or destroyed buildings at 619 schools throughout Taiwan. In the two worst affected counties, Nantou and Taichung, 43 elementary and junior high schools were completely destroyed. At Kuangfu Junior High School, located right on the Chelungpu fault in Nantou County's Wufeng Rural Township, the sports ground was lifted up by a full two meters, and the buildings which stood along the fault line were reduced to a jumble of twisted rubble. The buildings of Chungshan Elementary School in Taichung County's Tungshih Township were almost totally flattened; only the school gate, its clock frozen at 1:47, bears witness to the instant when the earth shook and the heavens spun.

The list of damaged schools goes on and on. In Taichung County: Tungshih Elementary, Tungshih Junior High, Shihkang Elementary, Shihkang Junior High; in Nantou County: Chungliao Elementary, Nankuang Elementary, Tsaotun Vocational High. . . . Even in Taipei City, over 100 kilometers from the epicenter, there were reports of damage at schools such as Chingmei Girls' Senior High, where a building collapsed, and Hsinyi Junior High, where classrooms were left leaning.

If the children had been in class when the earth suddenly began to shudder and the floor bucked like a dinghy in a storm, should they have crouched under their desks, or run outside? When classroom walls began to tear like paper, windows exploded into flying shards, and lamps and cupboards danced through the air, would teachers have had the courage and the knowledge to guide the children to safety?

It is not only on this score that people are thanking their lucky stars. If the quake had struck in the evening when people were cooking their meals, how many would have had the presence of mind to turn off their stoves and switch off the electricity before fleeing? In neighborhoods with mains gas, who would have known how to shut off the valves to each flat, to each building, or the main valves buried under the street? The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, with a main tremor of magnitude 8.25, was followed by a fire which raged for 74 hours and destroyed 28,000 buildings; it was only extinguished by the providential arrival of a rainstorm.

Why do earthquakes give rise to such terrible infernos? Huang Jenn-shin, who heads the Information and Development Division at the National Science Council's National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering (NCREE), and who previously worked for the California state government, explains that ground movements during an earthquake rupture water mains, causing a loss of pressure, so that even when firefighters do come on the scene they can only watch the flames helplessly. Even more frighteningly, as the fires on the ground continue to blaze, the billows of smoke rising up from them are cooled by the atmosphere and sink down again; as this cycle is repeated, the oxygen at ground level is quickly used up, leaving people with little chance of survival.

To imagine yet another scenario, what if the earthquake had struck the Greater Taipei conurbation, with its crowded high-rises? With buildings of different heights smashing into each other as they swayed at different periods of oscillation, MRT tunnels collapsing, underground trains jumping the rails and underground oil and gas pipes exploding, what kind of apocalyptic scenes might have resulted?

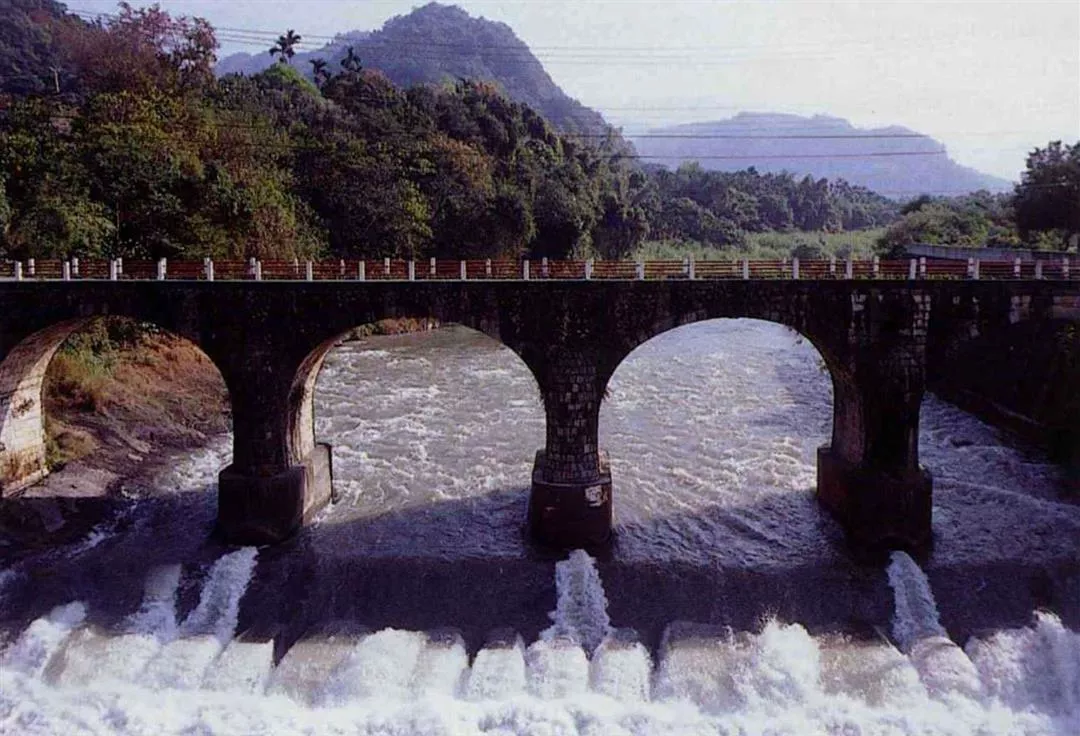

Nuomi Bridge in Peikang Village in Kuohsing Rural Township, Nantou County, is over 100 years old, but to the amazement of local people it survived the earthquake completely unscathed. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Learning to live with earthquakes

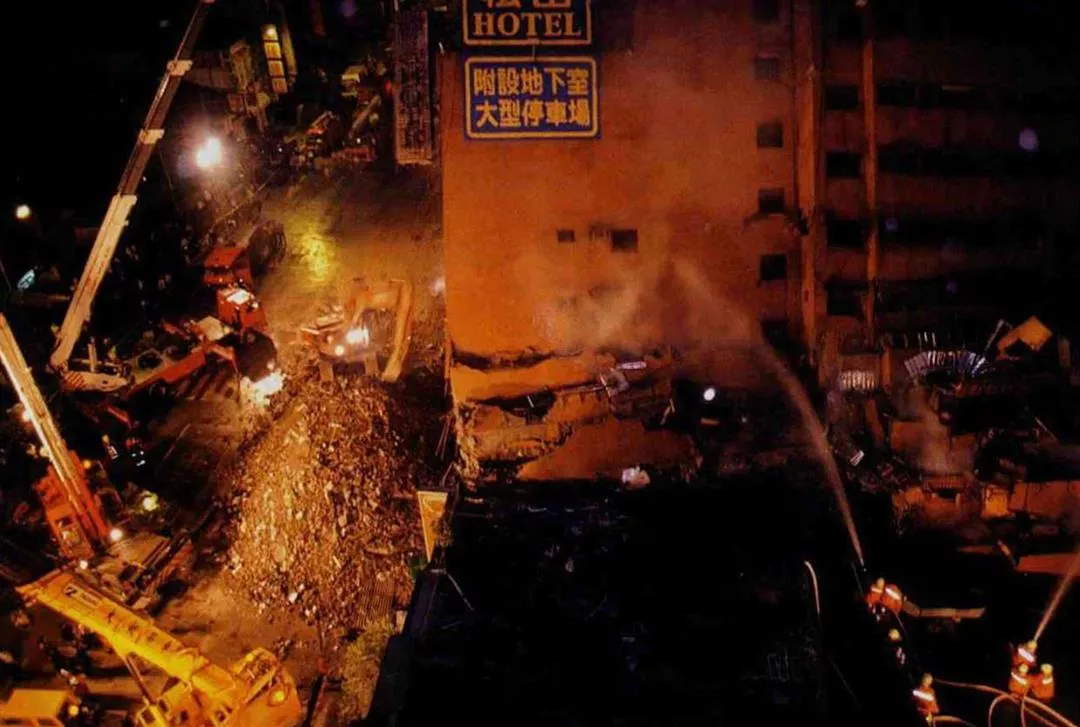

We are thankful for the good fortune which averted a much worse disaster. But many buildings collapsed which shouldn't have-including more than 20 high-rise blocks islandwide which toppled while others around them remained standing, claiming nearly 400 lives. In addition, many people were killed or injured because they lacked basic knowledge on how to behave in an earthquake, and many others died a miserable death trapped under rubble because rescuers could not reach them in time. These are things we must not forget.

The first step towards earthquake preparedness lies in "learning to live with earthquakes." As Huang Jenn-shin points out, the island of Taiwan owes its very existence to earthquakes, having been pushed up out of the sea by the collision of two tectonic plates. Taiwan's 51 known fault lines criss-cross our little island like random sword strokes hacked into its face. But how many fault lines remain undiscovered? Scientists can only guess "thousands."

Since the 21 September earthquake, Professor Wang Chien-ying of National Central University's earth sciences department has traveled the length of the Chelungpu fault several times. "Chelungpu is a classic reverse fault. The east side of the fault was thrust diagonally upwards, and more or less everyone living along that side was killed or injured. But although the west side was subjected to the same violent shaking, most of the buildings remained standing."

Unusually for an earthquake in Taiwan, there was a clear relationship between the 21 September quake and the Chelungpu fault. Hence after the catastrophe a consensus emerged that public-use structures should be situated to avoid fault lines, and that building in fault zones should be restricted. However, many academics say privately that this approach is "merely seeking psychological comfort," because most faults are buried tens or even hundreds of kilometers below ground, and when there is movement along one, no-one can predict where the seismic waves will reach the earth's surface. Furthermore, on this occasion the epicenter-Puli and Chichi in Nantou County, where casualties were severe-was not in a recognized fault zone at all. Who can explain why, when the "Earth Bulls" fought, they chose this spot as their main battleground? Considering the large number of faults all over Taiwan, anyone hoping to find a completely safe place to live really would need luck on their side.

In short, there is no reliable way of forecasting earthquakes, or of avoiding fault lines. "Earthquakes are in Taiwan's future, so rather than denying or ignoring them, or making a lot of useless predictions, or kidding ourselves we can move to safer areas, we'd do much better to buckle down and learn how to make ourselves stronger so that we can live with earthquakes," says Huang Jenn-shin.

Just as toddlers are sure to fall over, and therefore need to be given safe areas to move around in, the first step towards "living with earthquakes" is to create a living environment in which we can remain relatively safe even in a major tremor. To this end, particular attention has to be focused on public facilities and residential buildings, because they directly impact the chances of survival of the people who live among them.

In the wake of a major earthquake, fire is one of the greatest hazards. When the Tunghsing Building in Taipei City collapsed, broken gas pipes caused a fire which robbed victims of any last chance of survival.

A day of shame for the building trade

"Actually, Taiwan's building regulations are pretty strict as regards earthquake resistance-no less so than in the US or Japan," says Wang Sen-yuan, former president of the Professional Structural Engineers' Association of the ROC. But such codes have to strike a balance between safety and economic considerations. They can never require all buildings to be strong enough to come through an earthquake of magnitude seven or above unscathed. Historical records going back 400 years do not record any major earthquakes in Nantou County, so it was classed as an area of "moderate seismic activity," and buildings were only required to withstand horizontal accelerations up to 230 gal (1 gal = 1 cm/s2). But around Nantou County's Minchien Rural Township, ground-level accelerations as high as 980 gal (1 g) were recorded during the 21 September quake-more than four times the level foreseen by the building regulations!

The destructive power of the earthquake was terrifying, yet on visiting the stricken areas one could see how damaged but surviving buildings had done their job of protecting the people inside them: here, a building which had been thrust upwards by a meter, exposing the walls of the basement which had now become the ground floor; there, an entire block which had slid 50 meters down a slope. Although the outside wall on its uphill side was angled out at 45 degrees like the wing of a startled bird, it was firmly propping up the whole building, which had not collapsed.

"That's how reinforced-concrete structures are supposed to behave," explains Wang Sen-yuan. "Even when they are badly damaged they should still remain standing, or before they do collapse they should give warning signs such as cracks appearing in beams and walls, so that people inside have time to escape after they notice them." But unlike these resilient structures, many newly-built apartment blocks came crashing down completely without warning. Many anomalies such as concertinaed individual storeys, rebars (reinforcing bars) pulled clean and straight out of the bases of columns, rebars snapped through like dry spaghetti, and even the joints between beams and columns filled out with cooking-oil cans, were reported to the world by the international media, to the shame of Taiwan's construction industry.

But were the more than 20 high-rises around Taiwan which collapsed "solo" isolated, untypical cases? Can those around them which stood the test be presumed safe? In private, construction industry insiders are generally pessimistic.

In the earthquake this building, housing a shop, "lost" a storey as the ground floor collapsed in on itself. Yet adults sent children into the building through cracks to retrieve valuables. This is indicative of the lack of alertness to danger which is prevalent in our country.

Safe as houses?

Wang Sen-yuan says that according to his own on-the-spot observations, a common feature of many of the collapsed high-rises is that "Too few binder bars were used in the beams and columns, and they weren't installed correctly." Wang began raising the issue of binder bars many years ago, but he never thought his words would prove so prophetic.

"The root of the binder bar problem is not skimping on materials, but skimping on work," says Wang, adding that this shoddy workmanship is closely bound up with the construction industry's customary subcontracting practices.

"Rebar assembly is generally subcontracted on the basis of the weight of steel used, at NT$4,000 a tonne." Wang says that under this system of payment by weight, no-one skimps on the main reinforcing bars, as they are heavy and not difficult to work with. But at every ten to 15 centimeters along the main bars, "binder bars" (also known as stirrups) of thinner rod should be wrapped around them, with their ends bent inwards at an angle of 135 degrees, to form a cage which ties the main bars firmly together. This task involves a lot of work for very little pay, so the small contractors who take it on "cut corners wherever they can," and architects or structural engineers who go to watch that the work is being done properly may even be faced with threats such as: "You come here again and I'll thump you!"

This pernicious practice is nothing new, but in recent years construction companies have increasingly made "financial management" their prime objective, while neglecting technical management, as the latter does not help their bottom line. Meanwhile, enforcement of Taiwan's building regulations has been lax, and the practice of engineers of all kinds "renting out" their licences, enabling unqualified people to sign inspection certificates, is widespread. These factors have combined to produce the bizarre phenomenon of older buildings standing firm while new ones completed within the last decade collapsed.

The Taiwanese construction industry's blatant disregard for professional expertise concerning structural requirements is also apparent from the inherent weaknesses in the structural design of many buildings. Recently the media has focused attention on controversy over arcades and "open-space" designs with raised ground-floor ceiling heights and large areas unobstructed by columns. But in fact such designs are encouraged or even required by current building codes. For instance, to create stylistic unity Taipei City requires arcades to be provided under all new buildings which front onto certain main roads. These arcades give pedestrians shelter from the sun and rain and are also convenient for shopkeepers. But it now turns out that designs with reduced numbers of walls and columns may create a "weak storey" with a greater risk of collapse. However, even if the experts give warnings until they are blue in the face, will ground-floor owners be willing to spend large sums on reinforcements? And will local governments have the determination to set time limits for mandatory improvements?

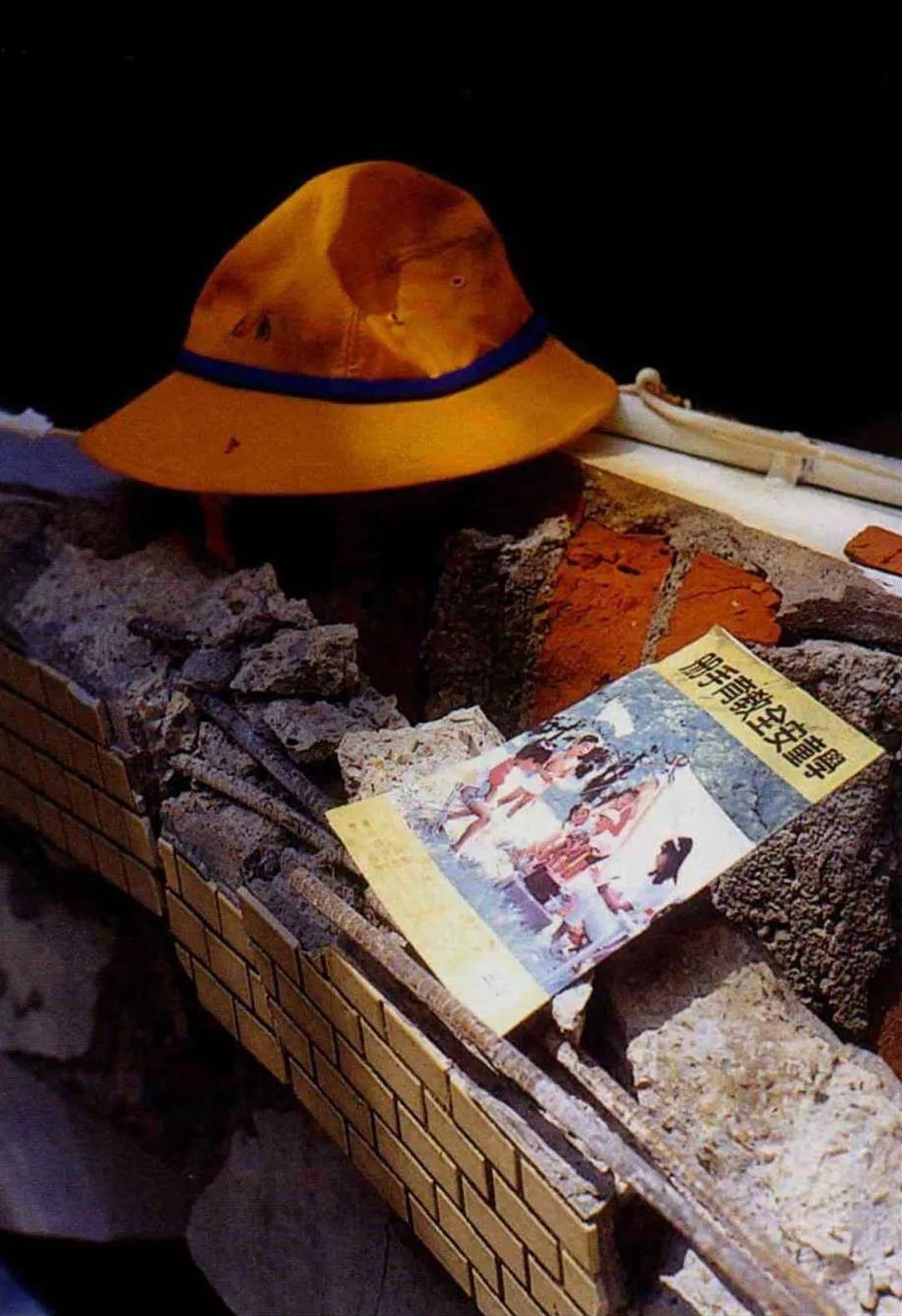

When classrooms disappear in a cloud of dust, we have to blame man as well as nature. Only if elementary schools are made safe can casualties be reduced to a minimum the next time disaster strikes. (photo by Hsueh Chi-kuang)

Don't make your home a death trap!

Worse still, says Li Tiao-yang, manager of the construction division of Shin Kong Life Insurance Company, "The moment many people buy a flat, they go on a grand renovation spree, and start ripping out walls and reducing or removing columns. Some of them even don't mind breaking into the services shaft, so that their upstairs and downstairs neighbors end up not even getting a proper TV signal." This is something many residents of high-rise apartment blocks have personally experienced. In the company's own 51-storey commercial tower block in central Taipei, lease contracts explicitly stipulate that before making any alterations, tenants must have them vetted by Shin Kong. Otherwise, "Some of them would put in new partition walls which block the effective range of the sprinklers, or shut up the fire hydrants in the storeroom, or even divide the emergency exits off into individual rooms." All these anomalies can be summed up in one phrase: "They're oblivious to danger!"

Some interior decorators will tell their clients: "Don't worry, I've looked at the drawings" (meaning the structural drawings of building). But unfortunately, the simplistic black-and-white notion that when making alterations, "you can do anything so long as you don't touch the main structural members" doesn't hold water. Especially in older urban areas such as Taipei City, most buildings were put up in the 1970s, when building regulations were less strict. They depend for their structural safety margin not on their columns, but on their brick walls, because as these walls move they generate friction and heat, absorbing and dissipating seismic energy.

"But today far too many of the brick walls have been torn out. When there is a big earthquake, what will be there to resist it?" Wang Sen-yuan cannot help frowning with worry.

Many people ascribe the serious damage to schools in the areas worst hit on 21 September to corrupt collusion between contractors and officials in the execution of public works projects. Some corruption may indeed exist, but in fact the nub of the problem lies in the type of structural design generally chosen for classroom buildings in Taiwan's elementary and high schools.

Wang Ching-chung, director of the Department of Construction Engineering at National Kaohsiung First University of Science and Technology, says that newer teaching buildings have "cantilevered" arcades (walkways covered by overhanging upper floors, without supporting columns on the outer side), and large classrooms without partition walls, but with windows and doors all along both sides. Columns are "trapped" between window sills, creating a "short column" effect. As for older buildings, just as with many older houses in small towns, when the original two-storey structures at many schools were found to be too small, third and sometimes even fourth storeys were built on top. With such inherently inadequate structures or botched additions, it is hardly surprising that buildings collapsed.

Killer display cabinets

The 21 September quake did indeed bring into the open many problems which had previously been overlooked or ignored. Huang Jenn-shin of the NCREE calls on local governments throughout Taiwan to grasp the opportunity to perform an all-round safety assessment of existing buildings, and then target priority sites-such as schools, hospitals, police stations, fire stations and shopping centers-for strengthening. But they should also strictly enforce building regulations in new buildings. Only by proper supervision of both old and new can there be any hope of reducing casualties to a minimum when the next major earthquake strikes.

The 7,000-member International Search and Rescue Association of China, whose bright red uniforms could be seen in all the stricken areas, is the non-governmental organization which received the most praise in the aftermath of the disaster. But Commandant Lu Cheng-tsung laments that disaster preparation in Taiwan is neither detailed nor comprehensive enough. For example, he says, when rescue teams in American cities arrive at a collapsed building, at the touch of a computer key they can consult the building's complete structural drawings, and see exactly where the bedrooms, stairwells and service ducts are, to assist their search. But in Taiwan, a building's drawings may be with the residents' committee, with the construction company or with the local government's building inspectorate, so finding them takes time. As to whether the building was really built according to the drawings, and whether owners have made structural alterations, that is anybody's guess.

A building's structural framework is the skeleton which holds it up, but the internal layout and even the arrangement of furniture can also provide opportunities for survival, or alternatively turn homes and offices into death traps. The story of the Sun brothers surviving in the collapsed Tunghsing building in Taipei City thanks to a big old refrigerator was widely reported, but few people are aware that in the stricken areas many of the dead were crushed by falling heavy furniture and electrical appliances, or were trapped by overturned furniture which blocked their escape routes.

In particular, with Taiwan's high property prices and limited space, both in homes and offices many people are in the habit of stacking furniture high; some cabinets have large areas of glass or are filled with fragile knick-knacks, while others are top-heavy and easily toppled by a quake.

To prevent this, "preferably the sections of large cabinets should be fixed together top and bottom and side to side, and they should be braced against the ceiling so that they don't have room to sway or topple," says Julian Chen, vice president for production at well-known office furniture manufacturers UB Office Systems Inc.

Furthermore, many companies take a shine to the spacious main corridors in their office premises, and cannot resist lining them with storage cabinets. If the drawers in these cabinets have no catches to prevent them rolling open, and are made of steel, with sharp corners, and especially if there is no emergency lighting in the corridors, then one can easily imagine how, when an earthquake hits, no matter whether the drawers slide out or the cabinets themselves fall over, even people lucky enough to escape will be tripped up and suffer cuts, while the unlucky ones will find their route blocked and will not make it out alive. (See "Five Steps for Protecting Yourself in an Earthquake.") Many companies are also in the habit of joining together room dividers in long rows. If one panel a meter wide by one-and-a-half meters high weighs 20-odd kilograms, then if an earthquake brought a row of them down on top of you, could you escape without injury?

Safer public places

Public facilities are an important component in creating a safe living environment. The recent Californian earthquake caused a train derailment in the Mojave Desert. How safe are Taipei's MRT lines?

"We have a link to the Central Weather Bureau, and we receive data within one minute after an earthquake." Mr. Tung, a senior engineer at Taipei Rapid Transit Corporation's central control room, states that if this data indicates that the earthquake's intensity in Taipei was less than four, trains will continue at reduced speed to the next station, where they will wait while station staff and maintenance personnel inspect the track. If no fallen debris, fallen electrical cables or other abnormal conditions are found, then after five minutes the trains can proceed again with caution. If the quake's intensity is greater than four, trains will not be allowed to run again until a more detailed general inspection has been carried out.

But if trains don't stop until the earthquake is over, what happens if the city is hit by a super-quake of magnitude seven or above? Would trains traveling at high speed be derailed? "I don't think so," says Mr. Tung: the Taipei MRT is fitted with automatic protection systems, and if the rails buckle or debris falls on the track, the trackside signaling system will immediately signal an abnormal condition, causing trains to brake automatically. Thus a derailment at the trains' full speed of 80 kilometers per hour is very unlikely.

After the 21 September earthquake, disaster prevention measures at large shopping centers also came under scrutiny. Li Kuang-jung, manager of Sogo Department Store's promotions department, says that the biggest worry for large stores is the power cuts and fires which may follow a quake. Hence Sogo has its own large diesel-powered generator which starts up within five to ten seconds after the electricity goes off, to restore 20-30% of normal power. Staff can then use the public address system to guide customers to the emergency exits. Also, the valves controlling the building's gas supply will shut off immediately if a leak is detected.

Next time let's be ready. . . .

No matter how comprehensive disaster prevention measures may be, they can never cover every eventuality, and this makes constant vigilance and awareness of risks all the more important. During the power cuts following the 21 September earthquake, many shopkeepers put up candles on their shelves and carried on trading as usual, while some restaurateurs put a candlestick on every table and began offering "candlelight rendezvous." "Everyone seemed to have forgotten that there was still a constant danger of aftershocks. What if several candles fell over all at once and set the place on fire?" worried Ms. Chen, a media worker.

People are forgetful, and as the nightmare of 21 September fades from memory, getting citizens to remain prudent and vigilant will be easier said than done. A recent survey in Japan, which had been on "full alert" after the Kobe earthquake, revealed that 34% of the public had made no special preparations whatsoever for a major earthquake-a full ten percentage points more than in a survey two years ago. Those who were unprepared mostly offered the excuse that they didn't think they would be "that unlucky." But if the dangers we have all been warned about today become the killers of tomorrow, there will be no point in bewailing the cruelty of nature-we will have only ourselves to blame.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)