When you hear the words "Hengchun Peninsula," besides sun and sea and sand, what do you think of?

Birdlovers say that there are 96 types of resident avians and 190 types of migratory birds, making it a birdwatchers' paradise. Geologists note that the local rock formations would make a good study. Biologists say that the large variety of plant and animal life here makes it like a natural treasure chest. Archaeologists have discovered artifacts that date back 5000 years. And the most exciting thing is the rich and varied maritime ecology; in fact a maritime museum is in the works.

And what do historians say?

In the middle of the 19th century, when Han Chinese as well as Western adventurers came to Taiwan in growing numbers, Hengchun was seen the way we see the Central Mountain Range today--as untamed "savage mountains."

But 120 years ago, after the Japanese launched the "Mutan incident," bringing the peninsula onto the Chinese historical stage, it became a national defense frontier. From this point on the area became developed, ending the way of life that the local indigenous people had known for thousands of years. After this Japan began the Sino-Japanese War, leading Taiwan to the fate of being ceded to Japan....

For the in-depth travel report in this issue, we take you back to the early days of the Hengchun peninsula to help you better understand this place. We will skip the well-travelled coastal route and head for the mountains instead! Because in the nooks and crannies of these forested peaks, our ancestors left behind marks of history.

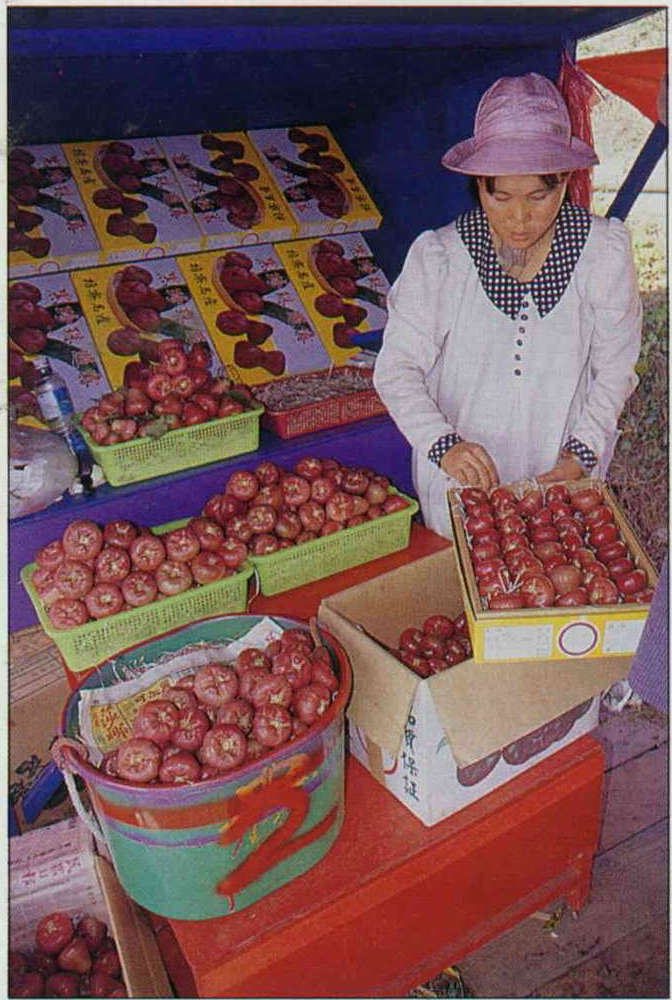

When you pass Fangshan in southern Taiwan, you begin to feel strong sea gusts in your face. To the side of the road a fish pond is dried up so you can see all the way to the bottom. On the pencil-straight highway from Pingtung to Oluanpi, there is vendor after vendor selling purplish-red "black pearls," a local specialty. As time passes into the depths of winter, the glaring sun still soaks into the earth here.

A Panamanian-registered freighter of over 10,000 tons suddenly pops up in front of you; it is cast onto the beach. "That was blown up here from the Taiwan Strait by that typhoon last August," complains an employee at the Fangshan Rural Township town hall. "It's really a hassle." The towing fee is too expensive, and it is impossible to break the ship up where it is; still less is the boat owner likely to show up to resolve the problem. So it has become "a huge piece of litter" on the Fangshan coast. Passing through the windblocking tree line, the whole family goes into the shadow of the hull to have a picnic, making for a cheerful roadside scene.

Standing at the side of the highway gazing out over the glittering green ocean and the fine white sand beaches, this ship can perhaps serve as a reminder of the great destructive power of the sea. The Hengchun Peninsula is famous for its coral reefs, but these are like hidden traps for ships. In the summer there are typhoons and in the winter winds race down from the mountains to whip up the waves. Since the mid-19th century, when European and American ships began to ply the South China Sea, an uninterrupted series of shipwrecks have occurred around here, out of which arose much of the area's historical fate for the past 100-odd years.

One hundred and twenty years ago (1874, or the 13th year of the Tung-chih reign of the Ching dynasty), Shen Pao-chen, a maritime official from Fukien, was ordered to go ashore on the Hengchun Peninsula. Looking at the mountains, there were the headhunting Paiwan people and other aboriginal tribes (the Ami, Peinan, Pingpu) to be overcome; looking seaward, there were a series of disputes arising from maritime disasters that needed to be resolved. Except for a thin stretch of western Taiwan's coastline settled by Chuanchow and Changchow Fukienese and a few Pingpu indigenous peoples, Shen was welcomed only by deep, forbidding mountains. The Han Chinese living on the coast called these "Fanshan," or "savage mountains."

As early as the late Ming dynasty (ended 1644), there was an incident in which the Dutch led a fleet to Kenting to massacre indigenous people who had killed Dutch sailors who had run aground in the area. Over the course of the next century, tales of brutality and vengeance unfolded one after another.

In the 5th year of the Hsien-feng reign of the Ching dynasty (1855), the American clipper ship High Flyer was lost here with the captain, his wife, and 300 China travellers. In the 8th year of the reign, a British commercial ship was cast onto the shoals by strong winds, and crewmen who made it to shore were killed by aborigines. In the year 10, Prussian sailors came ashore at Hengchun and fought a battle with indigenous people. In the 5th year of the Tung-chih reign (1866), a British warship fathoming the waters along the coast was attacked in Tantsu Bay....

Seven years before Shen Pao-chen stepped ashore on the peninsula, the incident of the threemasted sailing ship Rover caused the United States navy to undertake two expeditions here to compel eighteen aboriginal settlements to sign a treaty of friendship. Also in this year, 2500 troops from Japan came ashore here, in retaliation for the killing of Okinawan sailors in Payao Bay three years earlier, and "punished the murderers" by wiping out the village of Mutan.

This turbulent island was a severe threat to the Ching Court's security in southeastern China. After paying reparations of 500,000 taels of gold to avert a war, the dynasty dispatched Shen Pao-chen to set up a county seat and to secure the frontier. With the December sun shining as if it were the first day of spring back in the interior, he decided to change the name of the place where he settled--previously called Lang-chiao in the Paiwan language--to "Hengchun," meaning "eternal spring." He went on to open up the mountains and subdue the indigenous people, taking the peninsula from the era of being an aboriginal stronghold to the "Hengchun" era.

When you pass Fengkang, you are now on the Hengchun peninsula. Along the main road through here, the Pingtung-Oluanpi highway, coconuts are piled up alongside the struts that hold up the tents of the vendors, inviting customers to quench their thirst with a refreshing cup of coconut milk. You can sometimes discover grilled shrike at little stands selling B-B-Q along the roadside, which is a rather disconcerting sight.

The roads of the Hengchun Peninsula are easy to follow and clearly distinguishable from one another. The Pingtung-Oluanpi highway runs straight down the west coast, linking together historically important settlements, and ends up at the very tip of the island at Oluanpi. Travellers need only follow the major road, and keep an eye out for the signs for the branch roads, and they can easily get to wherever they want, up into the mountains or down by the sea.

Checheng (which means "cart city") is a population center set where the Ssuchung River empties out into the sea. Onions, the local specialty, are piled into little mountains along the roadsides. More than 300 years ago, Ming General Cheng Cheng-kung (Koxinga) hit the beach here, and after routing Paiwan forces cleared land and stationed troops on this spot. This was the largest settlement in the peninsula prior to the construction of Hengchun.

It is said that the Paiwan, who retreated to the mountains, were unhappy there and frequently came down to raid. The residents built a city wall out of firewood, so the place also got the nickname "Firewood Town."Now that attacking had become more of a challenge, the indigenous people organized 18 settlements together for a joint assault. The residents, fearing the aborigines would set the city wall alight, stacked up tens of oxcarts to build another wall outside the original one, and, after a fierce battle, finally pushed the attackers back into the hills.

The "Firewood City" or "Cart City" of those days has disappeared without a trace. The modern buildings now lining the streets of Checheng have eradicated any lingering historical value, and sinified Paiwan people use Taiwanese to haggle over vegetables with the Chinese. Today's Checheng is just a replenishment point for travellers heading further south.

Turning in next to the Checheng Farmers' Association where the sign points to "County Road 199: To Ssuchunghsi," you can see ironwood trees, onion fields, coconut trees, decrepit old houses, and even the odd slow-moving oxcart. Not far away is the gently flowing Ssuchung River, and in the dry season its water trickles very slowly as it weaves its lazy way through sunlit southern fields.

Next to some private houses at the Tungpu bus stop of the Taiwan Bus Company, a winding trail amidst long grasses beckons one to explore. Passing through the coconut groves you come to an open space. All you can see is a huge stretch of farmland, until the path pulls you left around a corner and you see a stone marker: "Gravesite of 54 Okinawan Foreigners." So this is the grave of the Okinawans whose deaths provoked the Mutan incident! In the 10th year of the Tung-chih reign of the Ching dynasty (1871), 66 residents of a small Okinawan island, returning home after travelling to pay their respects to the Okinawan king, were blown off course all the way down to the mouth of Payao Bay on the eastern side of the peninsula. Fifty-four were killed by indigenous people from the Mutan settlement, and 12 were rescued by Han Chinese. The bodies of the unfortunate victims are buried here.

The cries of the slaughter are now but a distant echo, and today there is only the sound of insects chirping in these quiet, empty fields. Seeing the silently vigilant marker one cannot help but wonder about the terror and shock these strangers must have felt as death approached....

Ssuchunghsi was one of the most renowned hot spring sites during the Japanese occupation. The place got its name (which means "four times over the river") because Shen Pao-chen had to try to ford the stream four times before he could make it across. During the Kuang-hsu reign of the Ching dynasty (1875-1908, during the latter part of which Taiwan was already under Japanese occupation), the local head of the Japanese military police fell in love with the clear, clean water here, and began building a small house and bathing area. After two more years, a Japanese came here to plant coffee and run a bathhouse, and the name of "hot springs" town began to spread.

Walking the cloistered and tranquil steeply rising path along the Ssuchung River, you can see still some shades of Japanese villas from those days. When the brother of the Japanese emperor came to Taiwan on his honeymoon, he built a vacation cabin here, which today is covered with moss.

The once-flourishing commercial settlement around the hot springs eased homesickness for many a Japanese, but with the end of the Japanese occupation era its prosperity began to decline. Although it was said that the waters here could cure stomach ailments, rheumatism, neuralgia, and skin disease, the high costs for food and lodging put it out of the reach of the frugal Taiwanese traveler. Today the hot springs village is a desolate place whose best days have passed her by.

In the past few years some corporations have thought about trying to revive the glories of yesteryear, and luxurious new hotels were built one after the other, but the incongruity of old and new on the streets only more eloquently attests to the estranged glories of the past.

About three kilometers further upstream along the Ssuchung River, there is a strategic pass formed where the slopes of Shihmu Mountain from the east and Wuchunghsi Mountain from the west face off against one another. Indigenous peoples have always called this place "Shihmen," which means "stone gate."

Wild grasses and shrubs have clambered over the dried up riverbed, and the sound of lambs bleating drifts in from afar. December has always been the dry season here, and with the wind skating down off the mountain, the whole area seems desolate. This place is the old battlefield where, 120 years ago, the Japanese, on the pretext of the deaths of the Okinawans, sent 2500 troops to attack Mutan and "punish the murderers."

The Japanese came ashore and bivouacked near Sheliao Village at the mouth of the Paoli River, on the west side of the peninsula. Unaccustomed to the climate, they were ravaged by tropical illnesses, and it is said more than 550 died within 100 days. After the debilitated forces regrouped, they set out in three columns to attack the indigenous people in their mountain settlements.

"The Japanese military followed the Ssuchung River, but the indigenous people had cut down trees to block their path and ambushed them from out of the grass cover, so on their first attempt the Japanese made it no further than the pass," points out Chen Shih-hsing, a history specialist at the Kenting National Park. He recreates the scene: "In order to cope with the aborigines concealed in the jungle foliage on both sides of the pass, the Japanese divided into two columns and surrounded the gorge; they attacked from behind, and the fighting was ferocious." On this site 400 warriors stood against 1300 Japanese soldiers. Though they had the advantage of terrain and guerilla tacties, the indigenous people were badly outnumbered and eventually crushed. The heads of the tribal chief and his son were cut off and set out on public display; the Japanese marched directly to Mutan and razed the place to the ground. The fields shook with cries of anguish.

This battle changed the course of the peninsula's history. The Ching Court began to awaken to the importance of defending the southeast, and to the dangers of Japanese militarism. They dispatched forces to establish the Hengchun settlement and began the work of educating the indigenous people and persuading them to stop killing shipwreck survivors.

The best view of the old Shihmen battlefield can be had from the top of a hill off to the side of the county highway.

After you hike the 394 stone steps up to the top of this hill, you are greeted by an upright stone commemorative plaque reading: "Cleanse the sea and space, return to us our rivers and mountains." This was put up after the restoration from Japanese occupation. Next to it is a large stone tablet which bears the marks of engraving, but the characters have been worn away so that it sits black and silent; it appears to be an ancient relic. It is said to be a commemorative tablet put up by the Japanese field marshal who led the punitive expedition.

Standing on the stone base looking outward, you can see all the contours of land and rivers below. It's easy to imagine that this was a lookout for the Paiwan people at that time.

The mountain winds careen through the gorge below, heading on their distant journey. Vegetation and clothes alike are whipped around. There is not a sound or even a wisp of smoke, as if nothing of note had ever happened there.

"Fanshan," which literally means "savage mountains," home of today's Mutan Rural Township and yesteryear's Mutan indigenous settlement, once made foreign sailors and lowland Han Chinese quake with fear. Heading deeper into the mountains from the old battlefield, you enter the forested mountains the Paiwan people call home. (You must have a mountain pass from the Hengchun police station to enter this area.)

The year after the Mutan incident (1875), because of the earlier Rover incident, both the United States and Japan requested that a lighthouse be erected on the southern tip of the peninsula. The Ching Court then dispatched a certain Mr. Beazeley, a member of the Royal Geographic Societyof the United Kingdom, to find a suitable spot for a lighthouse here. At that time in the mountains he saw "natives with pronounced musculature carrying bows, arrows, and long knives; they were nearly naked, wearing only small blue cloths around their waists." Today these indigenous peoples have been assimilated into lowland culture. Truckload after truckload of earth and construction materials is driven in and out of the restricted mountain area; the verdant peaks have been stripped down to a sickly yellow. The Mutan reservoir is under construction, and the village is enveloped in a cloud of dust. For the entertainment of the large number of outside workers brought here, in the past couple of years a few "wine houses," "recreation centers," and "chicken houses" have sprung up along the road.

Inside the restricted mountain area, a few tens of households make up a village. With most of the men working outside their villages, the remaining residents are women, children, and the elderly. They carry satchels on their backs in the traditional way, containing their food, cigarettes, betel nuts, and rice wine, doing this and that in the vicinity of the village to get by. The descendants of the Mutan warriors need no longer fight ferocious battles, and live far more comfortably.

An old woman is tending a herd of water buffalo, and egrets hop about. A group of children playing in the upstream portion of the river use an old net in a timeless, ancient style, waiting for their catch to wander into their mesh. "Come back and check in the afternoon," says one third-grade boy with all the authority of a commanding officer.

All along the mountain road, the colorful birds never stop their singing. The crested serpent eagle, unique to the Hengchun peninsula, circles overhead. From time to time a migratory or resident bird like the crested goshawk, black bulbul, or brown shrike might alight from the branches and take wing.

"We are now in the center of the southernmost peninsula of Formosa; after scaling a mountain, we see the Pacific Ocean for the first time. A river valley gives way to high peaks. Going through the gorges and cliffs of the mountains we can come nearer to the great ocean of which we have read or heard. A number of imposing mountains are arrayed to our left, part of the island's watershed. The mountain to the right is the southernmost promontory, one extremely isolated and sharp peak...." This is the description of the Mutan mountain area in Beazeley's travelogue.

Standing on the same mountain, the view to the left is of the southern vestiges of the great Central Mountain Range. To the right we gaze upon the peak on the southern tip of the peninsula. Ahead, the Pacific coast can just be made out. Beazeley was walking along a ox path; today, you can follow the wide county road all the way from Checheng, along the Ssuchung River, and wriggle through the mountains all the way to Hsuhai Village on the east coast.

After getting to Hsuhai and following Provincial Road 24 southward a bit, you come to the coastal defense outpost. You can only go through if you have a special pass. This is where the missile testing range of the Chungshan Institute of Technology is. Travellers may only pass through, but cannot stop. The restricted area begins at the mouth of Chiupeng fishing village and goes south along the coast road (Nanjen Road), until you enter the Nanjen Mountain Ecological Preserve.

On the side of Nanjen Mountain facing the Pacific, 600-year-old Paiwan stone houses lie in the obscurity of dense forest. This is one of the most famous, yet least-visited, historical protected areas on the peninsula.

From the white-walled, red-bricked house at number 11 Nanjen Road, follow the rugged, narrow path upward. Trees are mingled together chaotically, and the underbrush runs rampant. Without an experienced guide it would be easy to get lost in the woods.

After walking into the woods for about 50 minutes, you head up a grassy slope from where you can see the undulating Pacific. Then, moving deeper into the dense jungle vegetation, you have to walk quietly to avoid provoking the "tiger-headed wasps" (vespa tropica). Now you pass into a dense foliage cover so thick that you can no longer see the sky, and are startled to see pile after pile of dilapidated stone houses, seemingly stealthily abandoned.

According to research in the Department of Anthropology at National Taiwan University, there are 38 structures set in four ranks at this site. The building material is sandstone drawn from the river valley that runs behind the houses. There is a command stand at the center of the settlement, and several stone mortars for grinding. According to records in the old Hengchun County Gazetteer there were originally more than 200 houses here. It is said that this was a settlement of "Luofo barbarians" less than 4 chih (about 130 centimeters) in height. The Paiwan people relate a demonic legend that those who move the remains will be cursed. There is also a story that the residents here were lured to the shore and there massacred by other aborigines, while the houses wait in the darkened forest depths for the return of their masters.

Returning to Chiupeng, following the winding County Road 200, the mountains here are part of Manchou Rural Township. The Paiwan villages along the road have also been largely incorporated into lowland culture. After driving on for nearly an hour, on the desolate ground below Tungmen bridge, there is an astounding sight of flames generated by natural gas. After the Rover incident in 1867, the leaders of the eighteen indigenous settlements led a delegation of 200 men to meet with the British consul from Hsiamen and negotiate a treaty here. The vicissitudes of history are now long past, and today "Chuhuo" (the place name literally means "fire outlet") is famous for being a natural barbecue pit.

Three kilometers from Chuhuo is the end of the county line--the east gate of Hengchun itself.

The year after Shen Pao-chen came to the peninsula, the building tools and materials arrived from Fukien, and work formally began on Hengchun. Five years later the low wall around the city had been completed, and artillery placements were added to all four gates (north, south, east, and west) to ward off attacks from indigenous peoples or foreign military units. The internal and external walls were each twenty feet thick, and there was a moat around the outside. Such was China's southernmost county seat.

People from the local towns and villages moved in and some of the building craftsmen stayed behind as well. Later, Fukienese trickled in to trade this or that, and Fukienese culture became the mainstream in the peninsula. At that time many men who came to Taiwan married aboriginal women; contacts between the indigenous people and the lowland folk increased rapidly, as did marriages and trade, speeding up sinification of the indigenous people.

But this city wall was not to last. A typhoon destroyed most of it 30 years later, and in 1945 it was again smashed by Allied bombing. In 1959, an earthquake devastated what remained of the wall, leaving only the four city gates. These are the most well-preserved examples of Ching city wall in Taiwan, and are considered a Class 2 artifact. Recently the Department of Social Affairs of the Taiwan Provincial Government appropriated funds for reconstruction of an imitation old-style wall more than 8,000 feet in length surrounding the city.

Standing on the east gate, inside the wall is a residential district, but outside is an open vista, which points in the direction of aboriginal villages. Some farmers are grazing sheep in the grassy field below the facade, and the newly built wall has become a natural sheep pen. Other folks have put up pigsties or feed their poultry, lending the place a rustic air.

The old city of Hengchun is the transportation hub of the peninsula. Checheng is through the west gate, while the east gate leads to Chialeshui and the mountains. Go out through the south gate at the extreme other side of town and you get to the Pingtung-Oluanpi highway, which leads straight down to the southern promontory of Oluanpi.

Beazeley compared Taiwan to a fish, with the mouth of the fish pointing toward Japan, and the south being the tail. The "Seven Star Rocks," dark coral formations in the Bashi Channel just off the fish's tail, are where most of the maritime disasters have taken place.

After the Rover incident, the British Consul in Hsiamen requested that the Ching Court set up two artillery placements on the coast to protect victims of shipwrecks from being killed by the aborigines when they got to shore. But to get to the root of the problem it was necessary to put a lighthouse on the southern tip of the island. In 1875, the Ching Court purchased the Oluanpi promontory from the Paiwan, and began work on the lighthouse the same year. Because of frequent raids by the indigenous people, it took seven years to finish the job.

To prevent further attacks, a fortress was built around the structure. The base of the lighthouse was itself an artillery emplacement, while there were rifle slits in the walls. There was a moat outside the wall and armed soldiers on patrol, making it into the world's first and only armed lighthouse. This brought to a close a half-century of disputes arising from maritime mishaps.

But the lighthouse was not destined to last long. It was used for 13 years before Taiwan was ceded to Japan in the 21st year of the Kuang-hsu reign period. The building was put to the torch on the eve of the withdrawal of Chinese troops. Three years later it was rebuilt by the Japanese, and that lighthouse is the one that still stands at Oluanpi. Today it shines 20 nautical miles out to sea with 1.8 million candle power, the most powerful lighthouse in Taiwan.

The dense primeval forest surrounding the lighthouse at that time was cleared, and today has been replaced by an open meadow. The average tourist isn't allowed to go to the top for a look-see, but you can use your mind's eye to gaze past the rifle slits, dry moat, or artillery emplacement, and see something of the arduous challenge of the initial settlement period.

In the past 300 years, the different names that have attached to this peninsula (savage mountains, eternal spring, Kenting National Park) symbolize its passage from untamed wilderness to modernity.

The tides come and go, and the mountains and valleys remain mute. The rising of the sun over the Pacific and the setting of the sun over the Strait of Taiwan go on the same as they ever have. Take up a stringed gourd and sing these new lyrics to the tune of the old song, "Remembering":"Remember how Checheng gained its fame on the banks of the Ssuchung River, or how fine were the hot springs at Ssuchunghsi, or the battleground at Stone Gate, or the sounds of young girls singing...." Most of the human interest stories of this place have been hidden behind the most famous of local tourist attractions, the Kenting National Park, and few people have ever bothered to find out about them. Even most of the Paiwan indigenous people, hawking rooms, selling their wares, and speaking in fluent Taiwanese, have forgotten their traditions of snake worship, tatoos, and hunting.

Besides enjoying the wind and the waves here, try paying a little closer attention--the mountains and rivers will come alive again and tell their stories of pioneering days in the peninsula.

[Picture Caption]

p.43

This Panamanian freighter, grounded by a typhoon last year, has already sunk two meters into the sand; it is a symbol of the many maritime disasters in Hengchun's history.

P.42

(left)Hengchun under the setting sun, leaving behind only a remote sense of history.

P.44

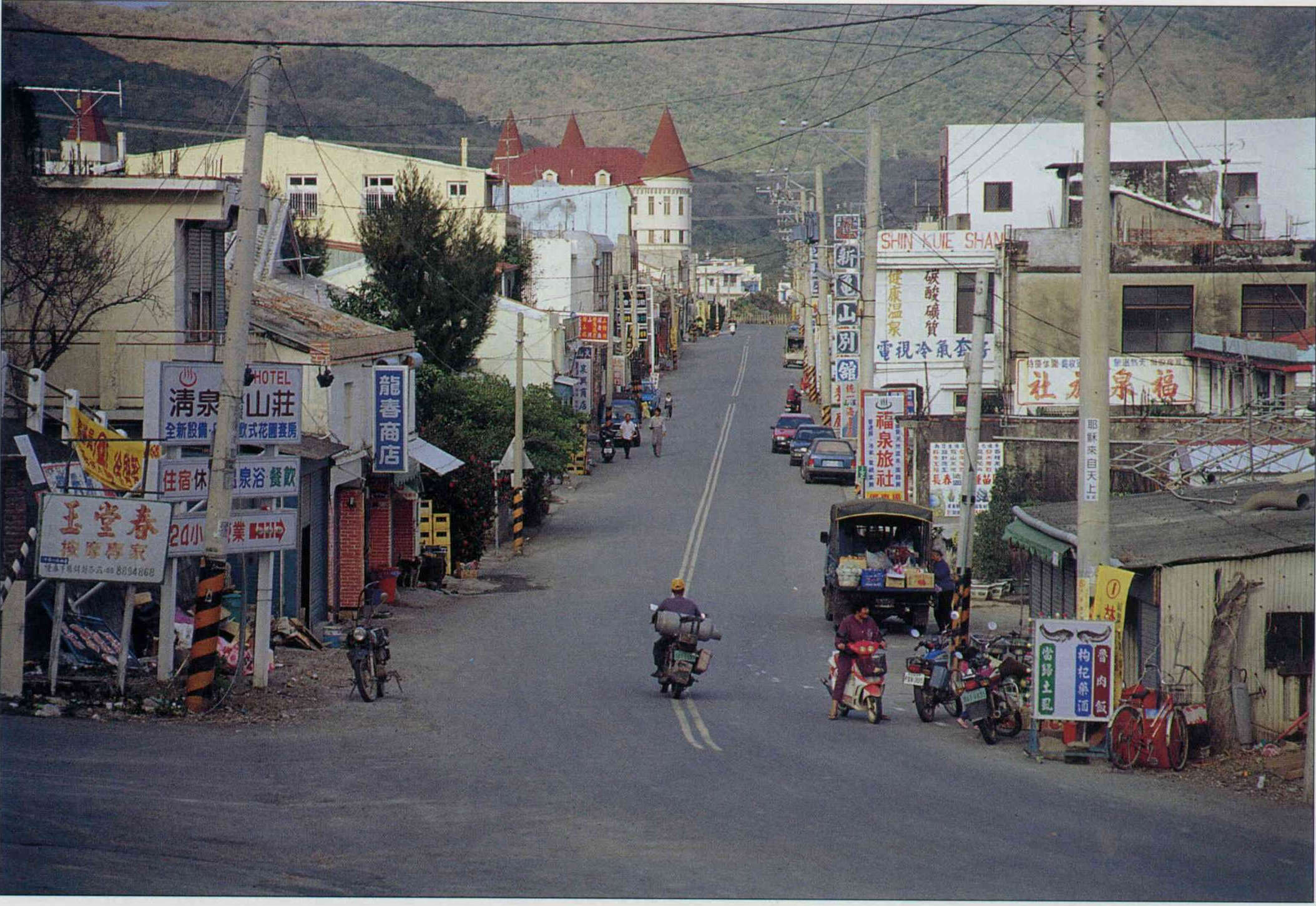

Ssuchunghsi was well-known in the Japanese occupation era for its hot springs; today the old streets are missing the prosperity of yesteryear.

P.45

This marker is for a group of Okinawan shipwreck survivors who set off one of the most important events in Taiwan's early history--the Mutan incident.

P.46

The mountains come together here to form an easily defensible pass; it was the scene of a battle between Paiwan warriors and Japanese forces.

P.47

On a hill by the old battlefield, all that is left is a commemorative marker.

P.47

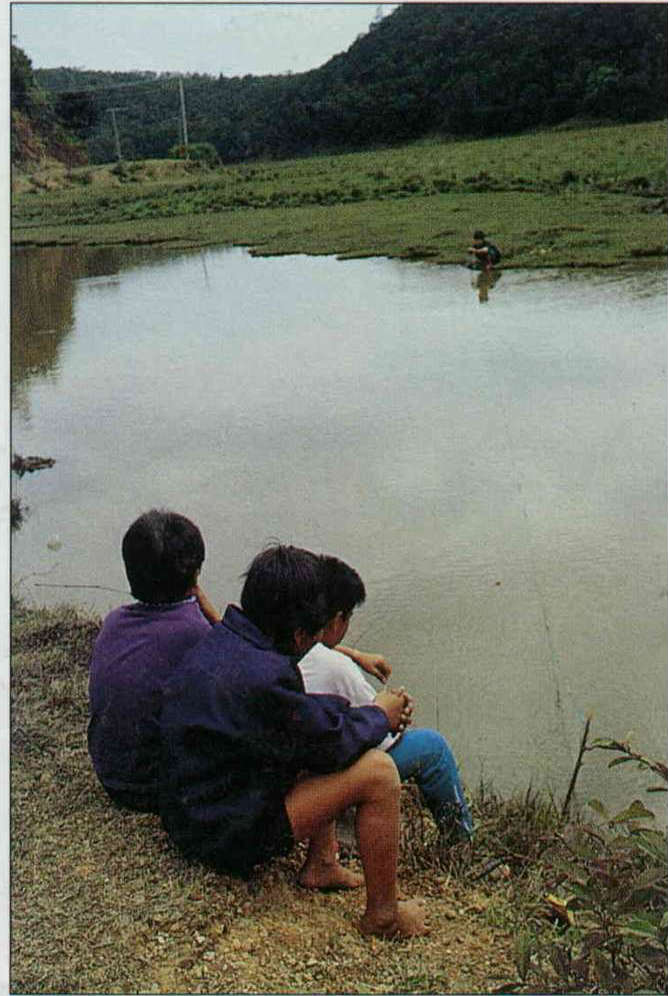

The Paiwan people are mountain dwellers. You can see the children playing outdoors here in the restricted mountain area.

P.48

Tachienshih Mountain is a landmark in the Hengchun Peninsula; the area at the foot of the mountain, formerly covered with vegetation, is today pastureland.

P.49

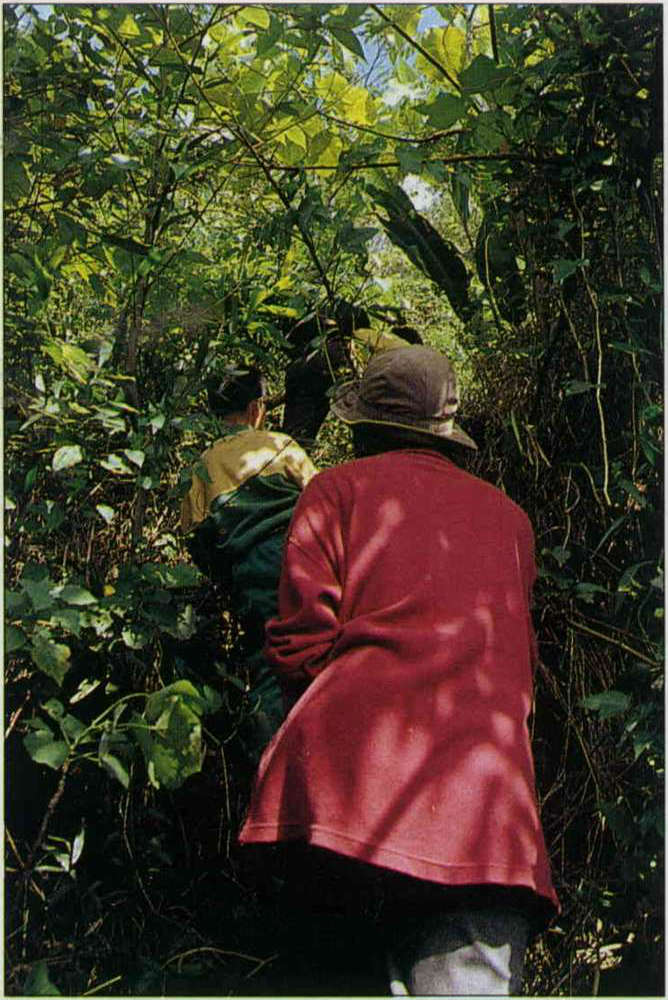

In the dense forest where the stone houses of Nanjen Mountain lie concealed, it is necessary to use a machete to move forward, giving one a deeper understanding of how hard it must have been for the first people to penetrate these "savage mountains."

P.49

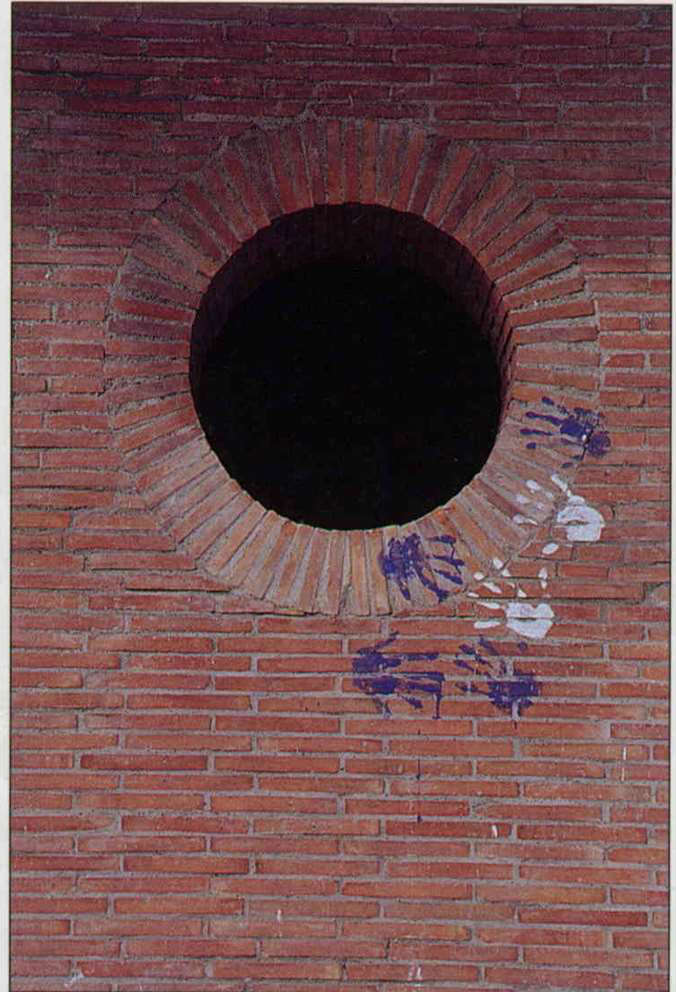

The collapsing houses have not been ravaged by mother nature alone; visitors have left graffiti. No wonder the government agency in charge doesn't want to open the area up more, and would rather leave the old relics as they are.

P.50

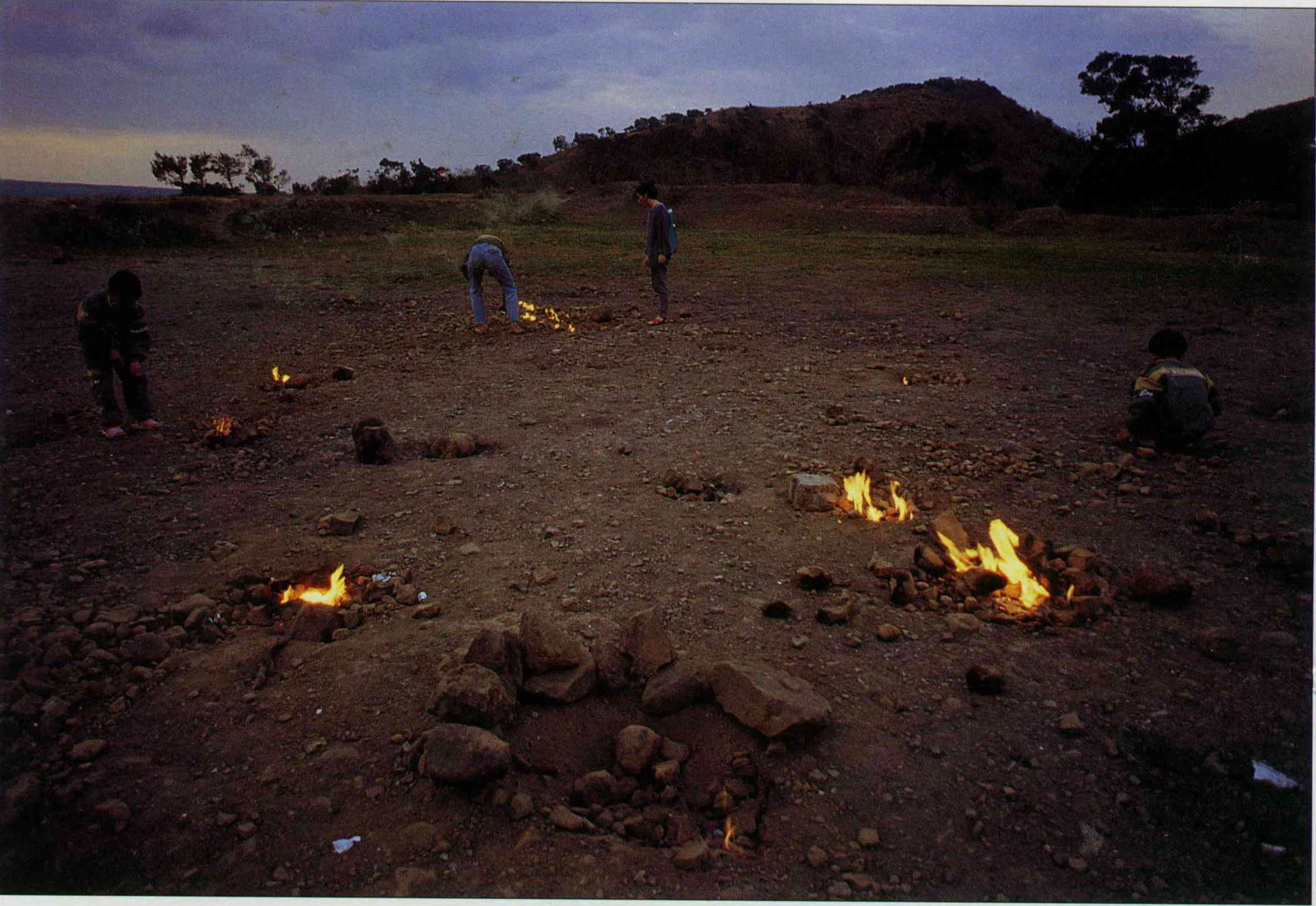

Here in Chuhuo (which means "fire outlet"), just dig a hole and start a fire; it won't go out, don't worry. Sometimes the locals come here for barbecue.

P.51

The south gate is the most bustling of the four city gates still standing in Hengchun.

P.51

The handprints on the old city walls of Hengchun make the tourism agencies worry about the character of local travellers.

P.52

The Oluanpi lighthouse was the only armed lighthouse in world.

P.53

Boxes of "black pearls," a local specialty, attract visitors.

P.54

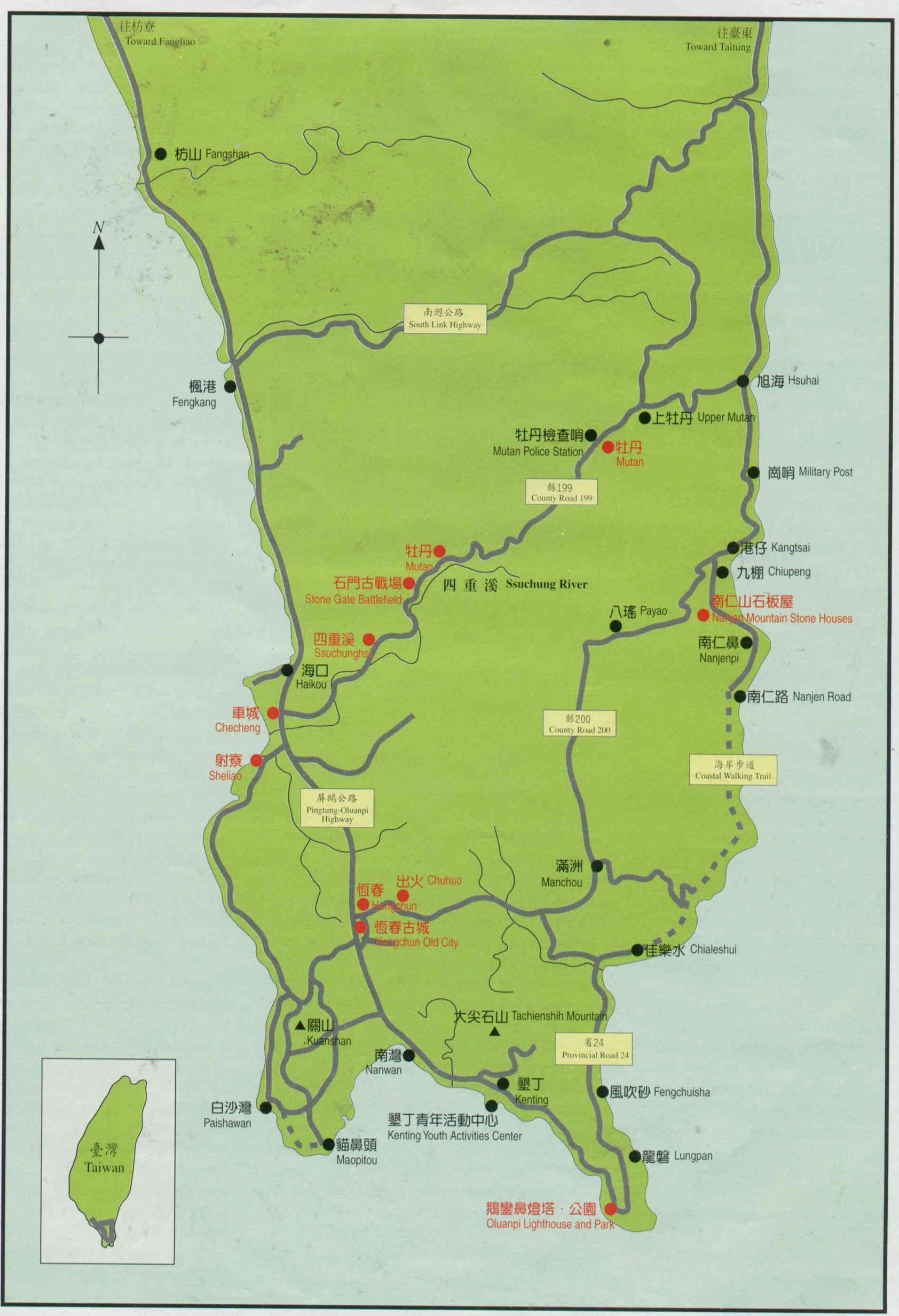

A Guide to Travel in the Hengchun Peninsula

Chencheng: Has the largest temple in Taiwan dedicated to the God of the Earth (Fu An Temple); it has been in existence continually since the Ming dynasty; there are many Ching dynasty era plaques and tablets inside.

Ssuchunghsi:Site of a hot springs which was very popular in the Japanese occupation era.

Shihmen (Stone Gate): Site of a battle between Japanese and indigenous forces in the 13th year of the Tung-chih reign.

Mutan: Paiwan indigenous settlement; fine mountain scenery and bird-watching.

Hsuhai: Hot springs area, but there are only two baths (one for men and one for women). The once-famous "Hsuhai Meadow" is now part of a military restricted area and visitors are not allowed.

Chiupeng: A pebble beach on the coast with unusual sand formations.

Nanjen Mountain: Site of 600-year-old Paiwan stone houses.

Chuhuo (Fire Outlet): Underground natural gas feeds perpetual flames.

Hengchun: Old city built in the first year of the Kuang-hsu era of the Ching dynasty; four city gates still stand.

Chialeshui: Coral and eroded rock along the coast, making for strange rock formations; also called "playground of the sea gods."

Fengchuisha: Desert scenery wrought by seasonal winds.

Lungpan: A broad open space with collapsed land, holes, red earth, and limestone; view of the Pacific Ocean.

Oluanpi Park: Site of the world's first "armed lighthouse," first built under the Ching dynasty and rebuilt by the Japanese.

Kenting National Park Forest Area: Includes Kenting Park and Sheting Park. The former is Taiwan's first tropical forest, offering mainly botanical sights. The main attractions at the latter are coral and tropical grasses.

Nanwan: The southernmost harbor in Taiwan; it is said that 1000 ton vessels were stopping here as late as the beginning of this century. With its fine white sand, it is the nicest beach in south Taiwan.

Maopitou: Located at the juncture point of the Strait of Taiwan and the Bashi Channel, it has had especially severe sea erosion. It is said that the bones of early Dutch sailors were hidden in Nanhai Cave below the cliff.

Kuanshan: There is a 100-year-old temple on the mountain top; in front is an observation platform to look at the sea or Maopitou. This is the best place to admire the sunset.

Paishawan: A white sand beach several hundred meters long; with its tropical vegetation, including coconut trees. it makes for lovely seaside scenery.

Sheliao: Where Japanese troops came ashore for the "Mutan incident."

Travel Information

Transportation Routes: The main road in the western Hengchun Peninsula is the Hengchun-Oluanpi highway. On the east coast there is Provincial Road 24. From Nanjen Road to Chialeshui is a walking path; vehicles cannot pass. Cutting across the peninsula are County Road 199 (from Checheng to Hsuhai) and County Road 200 (from Hengchun to Chiupeng and Kangtzu). Both are winding mountain roads, and are in good condition.

Transportation: Only the Taiwan Bus Company operates anywhere in the Hengchun Peninsula, and the headquarters is in the town of Hengchun. There are five buses a day that run from Hengchun along County Road 199 through Checheng to Hsuhai; the trip takes about 70 minutes. There are only three buses a day (morning, afternoon, and evening) that run from Hengchun along County Road 200 through Manchou to Chiupeng; the trip takes about an hour. There are 11 buses per day that run down the Pingtung-Oluanpi highway through the recreational spots of Nanwan and Kenting, ending in Oluanpi. The trip takes about 25 minutes. Travellers might want to call the Hengchun station of the Taiwan Bus Company for departure times; the phone number is (08) 889-2085.

If you don't want to drive a car down yourself, there are many car and motorcycle rental agencies in Hengchun and Kenting. There is a gas station in Hengchun; travellers in Ssuchunghsi or Manchou may fill up from shops selling cans of gasoline.

Food and Lodging: The two main concentrations of food and lodging are Hengchun and along the coast near Kenting. There is a small night market in Hengchun. In Kenting, aside from the Teachers' Hostel, the Kenting Youth Activities Center, and several well-known tourist hotels, the most unique lodging can be found in homes of local citizens who rent out rooms. Besides nailing down the price beforehand, it is best to check out the room and compare a few places before settling in. There are many seafood restaurants on the coast.

Along the road from Checheng to Hsuhai there are hot springs hotels at Ssuchenghsi. There are one or two small diners in Mutan; there is also one vacation center in Chiupeng. There are also small hotels and diners in Manchou. However, it is hard to find food or lodging in the mountains, so you might want to bring a snack along from Hengchun before heading up the mountain road.

Itineraries: The Hengchun Peninsula is not large, so trips can be rather flexible depending upon personal preferences. Below are two suggested itineraries: a "historical tour," and a "historical tour plus Kenting National Park." Those taking buses will have to pay close attention to departure times.

(1) Historical tour: Two days and two nights or two days and one night.

First day: Stay over the night before in Ssuchunghsi, and get an early start the first day. First go to Checheng to see Fu An Temple, then to Tungpu to find the Okinawan gravesite. Pass along the Ssucheng River to the Shihmen (Stone Gate) Battlefield; pass Mutan Village and the guard post for the restricted mountain area, and head toward Upper Mutan and Hsuhai, taking in the mountain scenery along the way. Pass by the coastal defense outpost and take in the coastal scenery on the way to Chiupeng.Then drive down Nanjen Road and see the stone houses. Return to Hengchun via Payao, Manchou, and Chuhuo; stay in Hengchun overnight.

Second day: See the old city of Hengchun, then play in Nanwan and go to the Oluanpi lighthouse.

(2) Historical tour plus Kenting National Park: Three days and three nights or three days and two nights.

First day: Same as above.

Second day: See the old city of Hengchun; go out the north gate and take County Road 200 and take the A route. Hike the coastal walking trail toward Chialeshui and take in the interesting geologic formations caused by sea erosion. Follow Provincial Road 24 and check out "Fengchuisha," the Lungpan scenic area, and Oluanpi Park; stay overnight in Kenting.

Third day: Follow the Pingtung-Oluanpi highway and admire the coastal scenery; visit the Kenting Forest Recreation Area, climb Maopitou, and watch the sun set.

Note: The above schedules may be rather tight; feel free to change them as you like, or even extend your stay.

Things To Remember: 1. To enter the Mutan mountain area you must first apply for a pass at the Hengchun police station; you can only enter by saying that your reason is to visit family or friends, work, or go hiking for exercise. If you want to take the road in the coastal restricted area from Hsuhai to Kangtzu and Chiupeng, you have to report to the Hengchun police station before you apply for a pass. Restrictions are strict, so prepare to be disappointed. The telephone at the Hengchun police station is (08) 889-7897.

2. The stone houses are located in an ecological protected area; visitors must be scholars researchers, and must apply first to the Conservation and Research Office of the Kenting National Park administration. To apply you need a research plan. The office number is (08) 886-1321.

3. The Park administration travelers' service center has eight lectures per day. Only groups of twenty or more persons can ask that a guide accompany them; you must apply first to the Guide Office of the Park administration.

Ssuchunghsi was well-known in the Japanese occupation era for its hot springs; today the old streets are missing the prosperity of yesteryear.

This marker is for a group of Okinawan shipwreck survivors who set off one of the most important events in Taiwan's early history--the Mutan incident.

The mountains come together here to form an easily defensible pass; it was the scene of a battle between Paiwan warriors and Japanese forces.

On a hill by the old battlefield, all that is left is a commemorative marker.

The Paiwan people are mountain dwellers. You can see the children playing outdoors here in the restricted mountain area.

Tachienshih Mountain is a landmark in the Hengchun Peninsula; the area at the foot of the mountain, formerly covered with vegetation, is today pastureland.

In the dense forest where the stone houses of Nanjen Mountain lie concealed, it is necessary to use a machete to move forward, giving one a deeper understanding of how hard it must have been for the first people to penetrate these "savage mountains.".

The collapsing houses have not been ravaged by mother nature alone; visitors have left graffiti. No wonder the government agency in charge doesn't want to open the area up more, and would rather leave the old relics as they are.

Here in Chuhuo (which means "fire outlet"), just dig a hole and start a fire; it won't go out, don't worry. Sometimes the locals come here for barbecue.

The south gate is the most bustling of the four city gates still standing in Hengchun.

The handprints on the old city walls of Hengchun make the tourism agencies worry about the character of local travellers.

The Oluanpi lighthouse was the only armed lighthouse in world.

Boxes of "black pearls," a local specialty, attract visitors.

A Guide to Travel in the Hengchun Peninsula.

Many foreign business people have been attracted to Taiwan by the ROC's consumer market for gold. Their stores have a different style from the traditional jewelers' shops.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)