Architecture Down on the Farm

Jackie Chen / photos Vincent Chang / tr. by Robert Taylor

December 1995

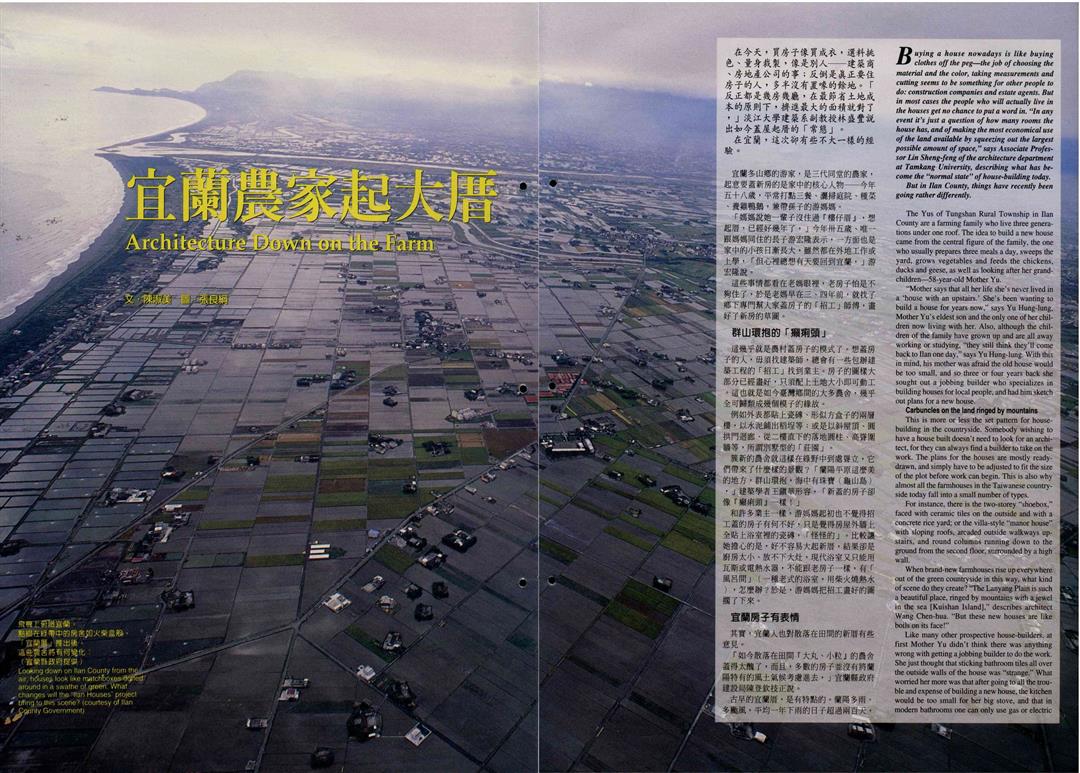

Buying a house nowadays is like buying clothes off the peg-the job of choosing the material and the color, taking measurements and cutting seems to be something for other people to do: construction companies and estate agents. But in most cases the people who will actually live in the houses get no chance to put a word in. "In any event it's just a question of how many rooms the house has, and of making the most economical use of the land available by squeezing out the largest possible amount of space, " says Associate Professor Lin Sheng-feng of the architecture department at Tamkang University, describing what has become the "normal state" of house-building today.

But in Ilan County, things have recently been going rather differently.

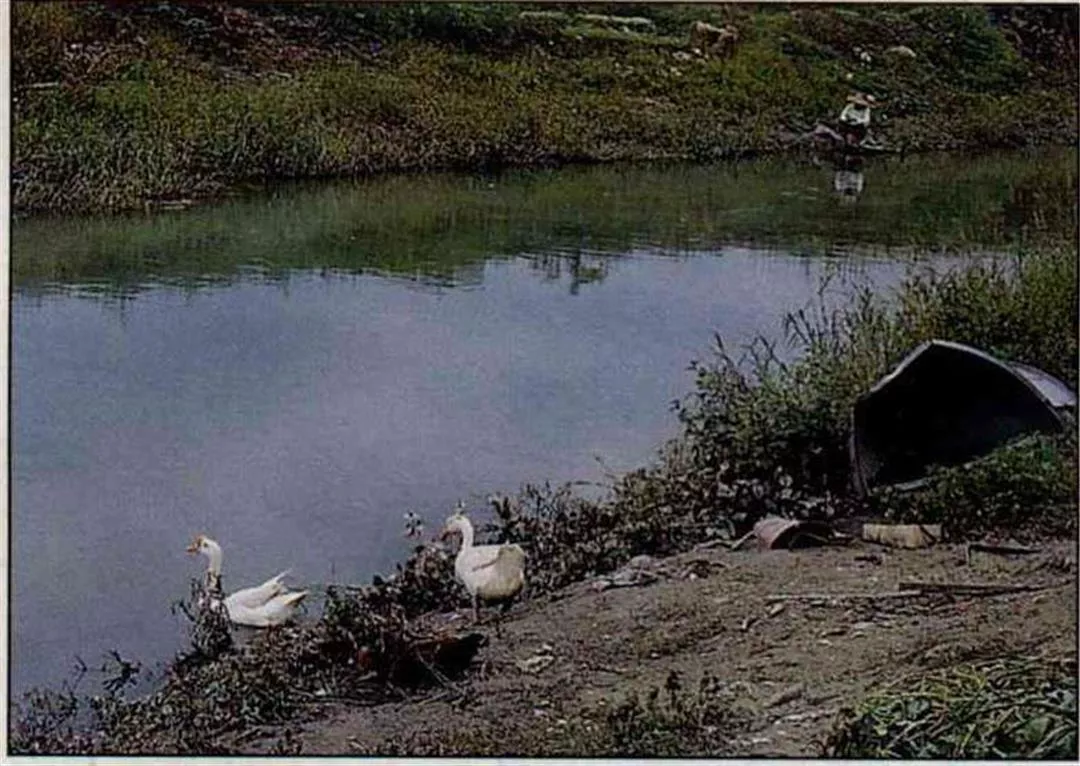

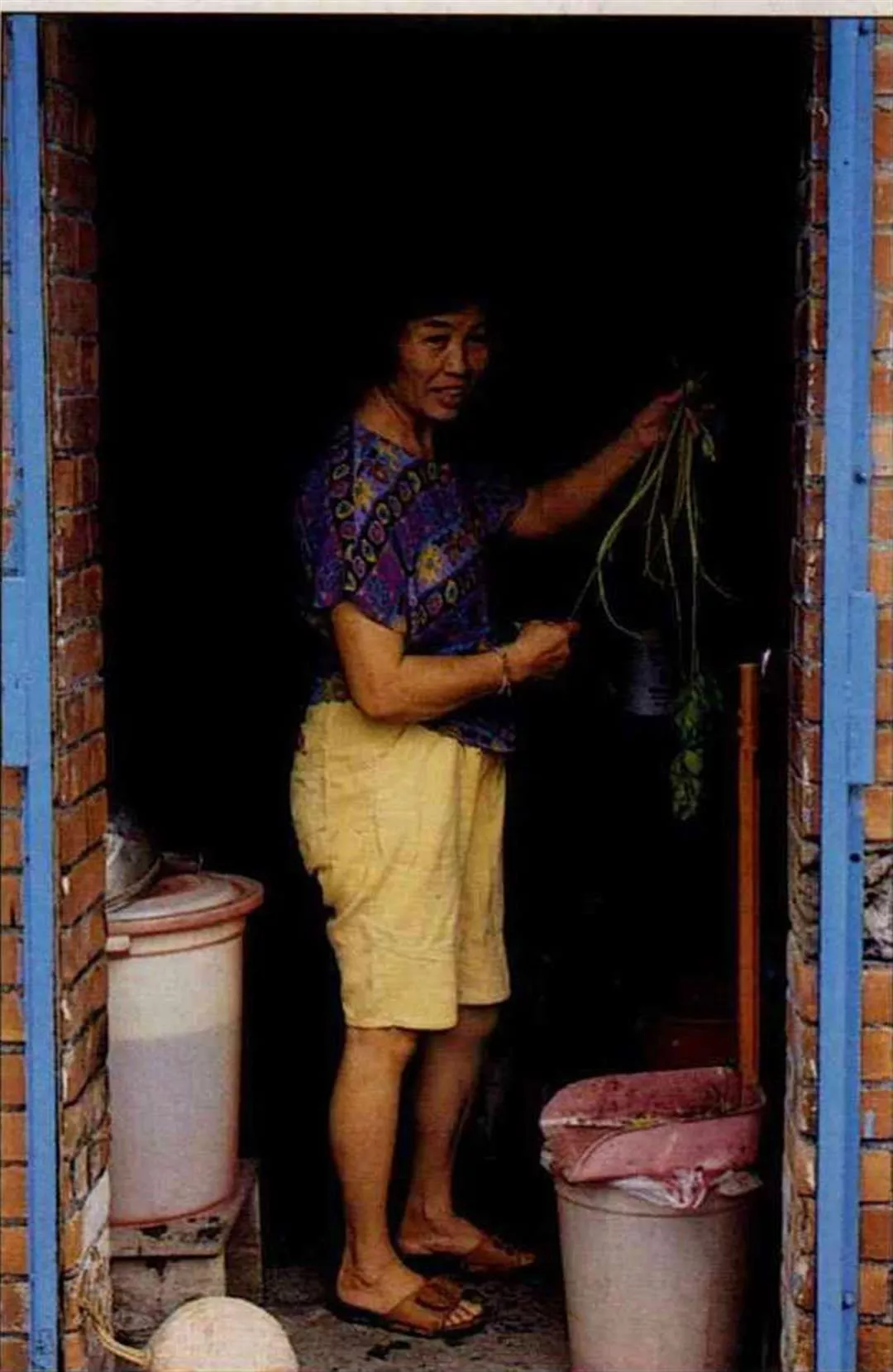

The Yus of Tungshan Rural Township in Ilan County are a farming family who live three generations under one roof. The idea to build a new house came from the central figure of the family, the one who usually prepares three meals a day, sweeps the yard, grows vegetables and feeds the chickens, ducks and geese, as well as looking after her grandchildren--58-year-old Mother Yu.

"Mother says that all her life she's never lived in a 'house with an upstairs.' She's been wanting to build a house for years now," says Yu Hung-lung, Mother Yu's eldest son and the only one of her children now living with her. Also, although the children of the family have grown up and are all away working or studying, "they still think they'll come back to Ilan one day," says Yu Hung-lung. With this in mind, his mother was afraid the old house would be too small, and so three or four years back she sought out a jobbing builder who specializes in building houses for local people, and had him sketch out plans for a new house.

The house designed for the Yu family by Huang Sheng-yuan combines flat and sloping roots, echoing the style of farmhouses widely seen in Ilan.

Carbuncles on the land ringed by mountains

This is more or less the set pattern for house building in the countryside. Somebody wishing to have a house built doesn't need to look for an architect, for they can always find a builder to take on the work. The plans for the houses are mostly ready drawn, and simply have to be adjusted to fit the size of the plot before work can begin. This is also why almost all the farmhouses in the Taiwanese countryside today fall into a small number of types.

For instance, there is the two-storey "shoebox," faced with ceramic tiles on the outside and with a concrete rice yard; or the villa-style "manor house" with sloping roofs, arcaded outside walkways upstairs, and round columns running down to the ground from the second floor, surrounded by a high wall.

When brand-new farmhouses rise up everywhere out of the green countryside in this way, what kind of scene do they create? "The Lanyang Plain is such a beautiful place, ringed by mountains with a jewel in the sea [Kuishan Islandl," describes architect Wang Chen-hua. "But these new houses are like boils on its face!"

Like many other prospective house-builders, at first Mother Yu didn't think there was anything wrong with getting a jobbing builder to do the work. She just thought that sticking bathroom tiles all over the outside walls of the house was "strange." What worried her more was that after going to all the trouble and expense of building a new house, the kitchen would be too small for her big stove, and that in modern bathrooms one can only use gas or electric water heaters-there's no space for a "furo" bathroom (an old-fashioned bathroom in which the water is heated by burning wood) like in the old house. What could she do? So Mother Yu laid aside the plans the builder had drawn up for her.

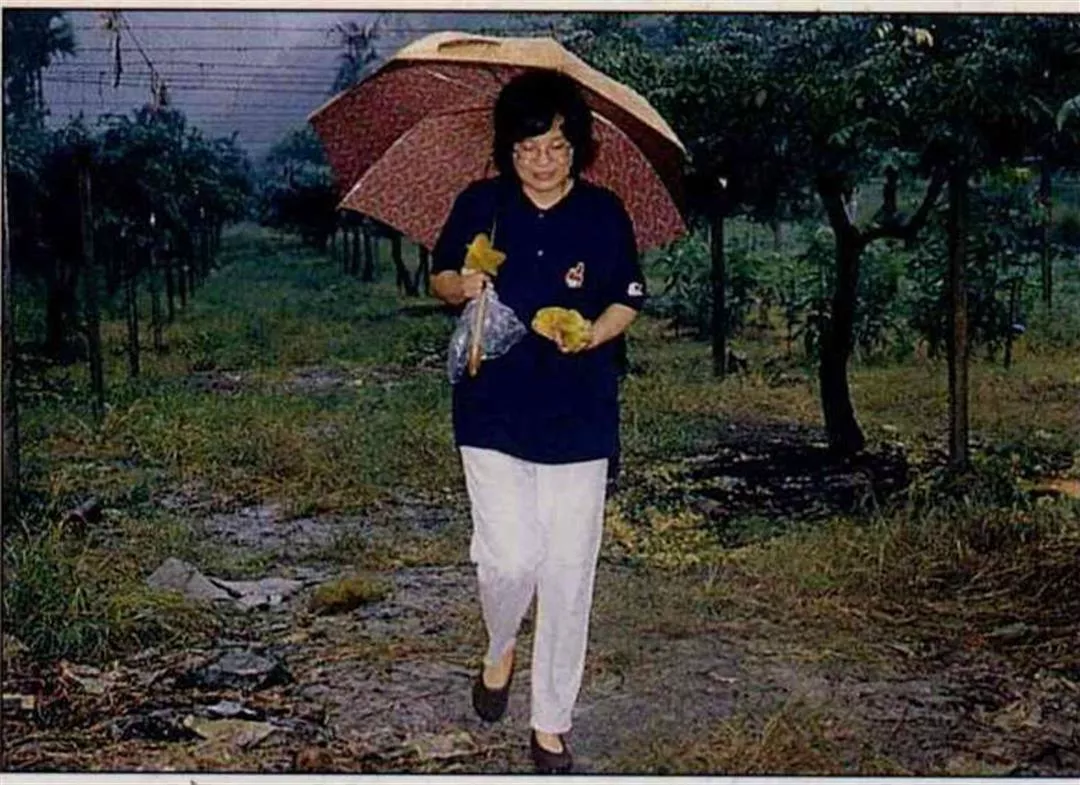

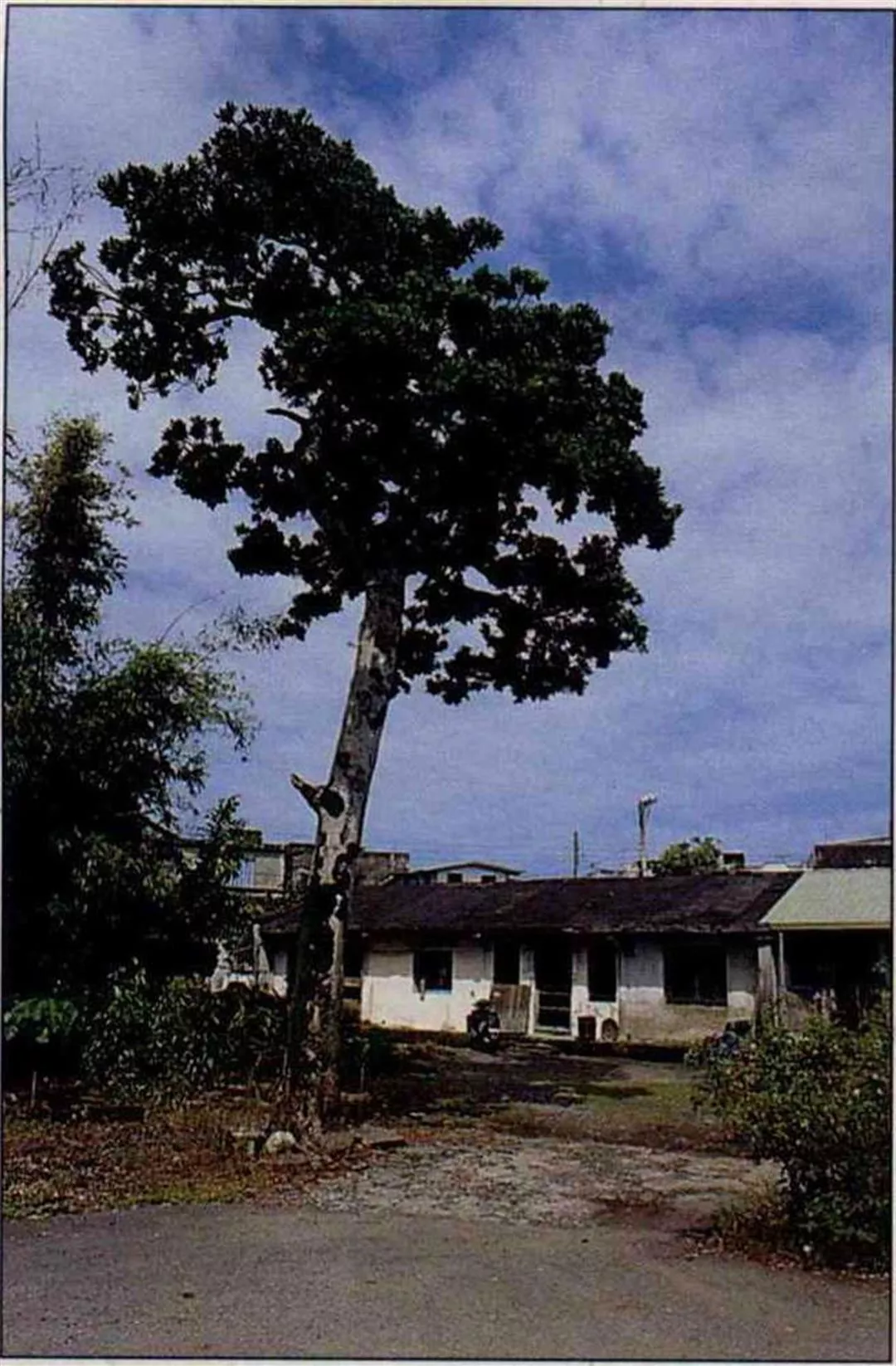

The Yus are a typical farming family who live three generations under one roof. Mother Yu's vegetable garden is close to the family's home.

Ilan houses are expressive

In fact, people in Ilan also have some things to say about the new houses dotted about the fields.

"The farmhouses which are now scattered around in the fields like boils and pimples really are terribly ugly. What's more, most of them give no consideration to Lanyang's special local climate," says Chen Teng-chin of Ilan County Government's construction bureau.

Old-style Ilan houses have special features. The Lanyang Plain is a place of much rain and frequent typhoons. On average it rains more than 200 days a year here, and typhoons can lift the roof off a house. Traditional dwellings used very direct methods to deal with these problems: "first avoid, then block." Professor Lin Sheng-feng explains that the most common method was for traditional courtyard farmhouses to be surrounded by a "green wall" of bamboo planted as a windbreak. Later, "typhoon shutters" were developed: thick wooden boards or metal plates which could be hung up over windows.

Ilan has a powerful summer sun, so at that time of year the black nets originally used to cover crops are used to shade the roofs of houses. The old builders' dialogue and compromises with nature naturally created the special style of houses in the Lanyang area. "With the changing seasons, the houses also express themselves in different ways," says Huang Sheng-yuan, an architect who works in Ilan.

The new farmhouses have none of all this. Whether in their materials or structure, they are transplanted from the cities, complete with tiled facades, windows of toughened, dark glass and so on. "It's as if you had built an arcaded city shop-type house in the middle of the paddy fields, or even plonked down a European-style luxury chalet villa," says architect An Yu-chien of Chu-chien architects' office in Taipei. When even the external appearance is transplanted in this way, she says, still less does the internal layout give any thought to the needs of working farmers, such as space for storing agricultural equipment, or productive activities like rearing poultry and growing vegetables.

In the noisy, crowded cities, emphasis is placed on commercial functions, so people have come to use such building materials as bright, easy-to-clean ceramic tiles and toughened dark glass. But when these materials are transplanted to the countryside, "in a farming area there's always mud and water about. If you cover the floor with ceramic tiles, with which you have to take your shoes off the moment you come in,and which become slippery and dangerous when wet, isn't this just causing trouble for yourself?" queries architect Huang Sheng-yuan. He adds that although toughened glass has its advantages in withstanding strong winds and heavy rain, on the other hand it also isolates one from the breezes, rain and dew, wasting the beauty of the countryside.

The Yus's back yard, which lies next to a branch of the Tungshan River, is where the family's chickens, ducks and geese are usually allowed to run. According to popular belief, geese will cackle when they see strangers, and their droppings frighten snakes away, so they are not usually slaughtered for food.

When architect meets farmer's wife...

In December of last year, Ilan County Government formally launched its "Ilan Houses" project. It publicly called on people planning to build new houses to participate in various categories based on geographical conditions in Ilan County, such as at the foot of mountains, in wetlands, or in suburban areas. Over 10 applied, and of these, nine projects were chosen and paired off with publicly selected architects, who were asked to develop "Ilan Houses" displaying local character.

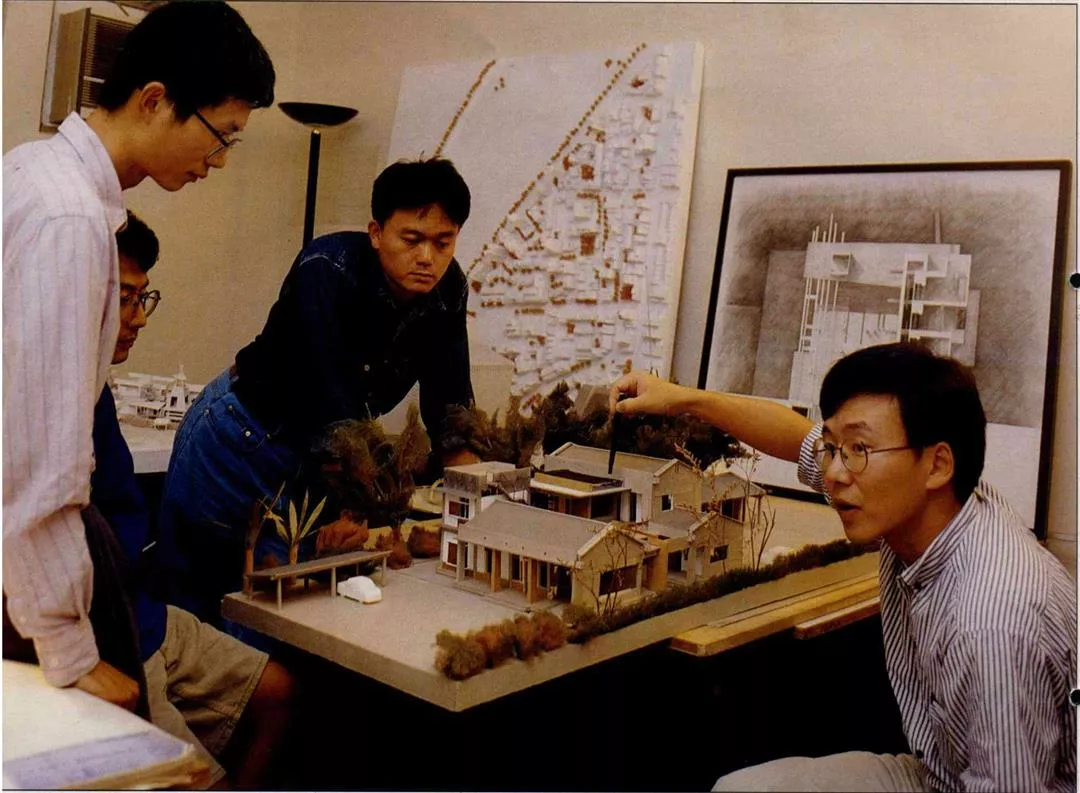

The Yu family's eldest son, who works for the county government, acted as go-between to get Mother Yu's plan considered for selection, and the architect she was paired with was Huang Sheng-yuan. Huang holds a master's degree in architecture from Yale University, and has practiced in the USA.

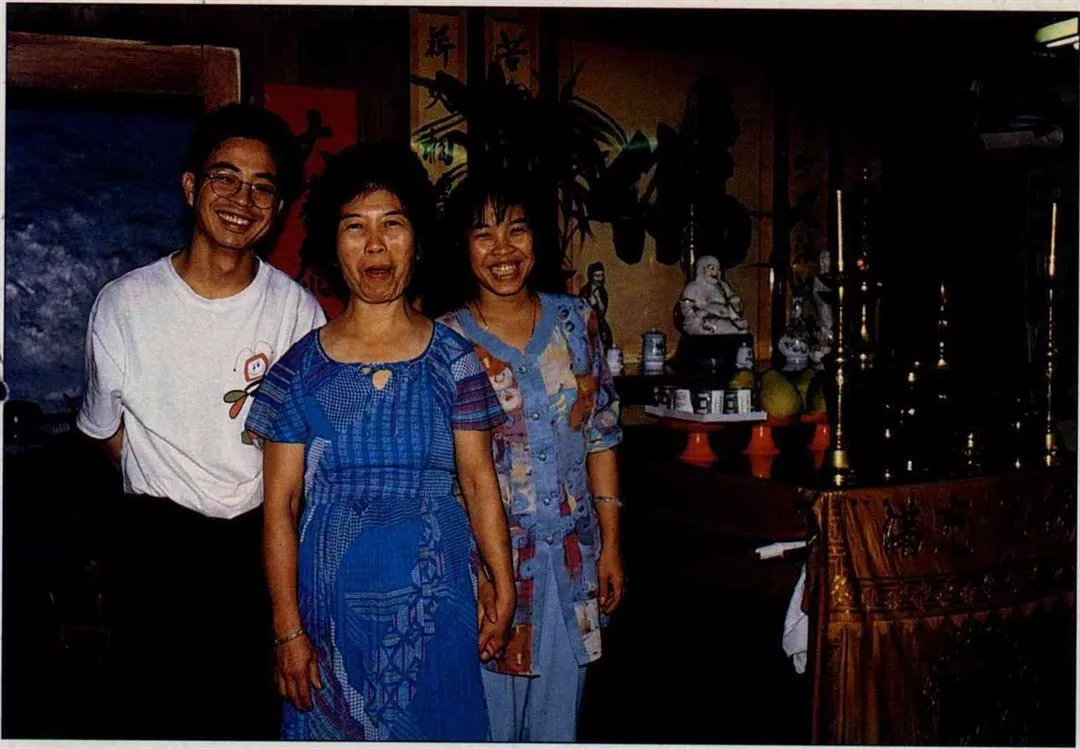

One is a traditional farmer's wife and mother, a lady with great agricultural expertise, the other a young architect with Western professional training-what kind of new house for the Yu family would result from their encounter?

Mother Yu had a number of requirements for the new house. Firstly, it had to have a big kitchen. Mother Yu says that with the three-meter-long row of kitchen units including sink, worktop and stove which are generally found in city apartments, "you don't have room to move," so you can't work properly. She also insisted on having space for a big wood-fired stove like in the old house. This has many uses: apart from being convenient for boiling water, stewing chickens and ducks, and making cakes and pastries at New Year, the family's waste paper and the twigs and leaves swept up from the back yard can all be used as fuel, saving money and helping protect the environment.

These are all very reasonable ideas, so without argument Huang Sheng-yuan designed a kitchen comprising a "dining area" and a "cooking area," with a combined size as large as two bedrooms. Furthermore, from the cooking area one can see the front gateway, because in rural areas often only the housewife is at home during the day, and she is usually at work in the kitchen. With this layout she can easily see if the postman comes or friends visit.

The kitchen in the new house also has a sink and work surface for preparing food, and space for all kinds of kitchen utensils and for pickles, preserves and condiments. Huang Sheng-yuan also specially designed a semi-outdoor area connected to the yard, for Mother Yu to prepare dried vegetables. While she washes and trims the vegetables, she can also chat with neighbors who drop in.

Mother Yu's second main requirement was that the new house must have a yard where her chickens, ducks and geese can run free. Apart from being slaughtered and eaten at annual festivals, these poultry lay eggs, "to give my grandchildren some extra nourishment." The fowl can also consume all the family's kitchen scraps, and "our leftovers won't go to waste." Not daring to slack, Huang Sheng-yuan designed several outdoor spaces all around the house for Mother Yu's use.

The wooden bathtub for the Yus'new house is ready and waiting.

No en-suite bathrooms

The toilets and bathrooms were also something Mother Yu was particularly concerned about. The furo bathroom, with which she is most satisfied, is separate from the main living area, and connects with the storeroom. It does not have an ordinary bathtub, but is dominated by a big traditional wooden tub, which keeps the water warm longer. There is also space for the big kitchen stove and the wood it burns. The whole house including the second floor, which is mainly for the use of the family's younger generation, has a total of three bathrooms with toilets, all of which are separate from the bedrooms. The Yu family insisted "we don't want ensuite bathrooms." This conforms to the traditional custom of having the toilet outside.

The outside toilets of houses in olden days were generally placed by the vegetable plot in front of or behind the house, and used as a source of manure, on the principle that "you don't waste your fertilizer on other folks' fields." Also, the potent aromas associated with traditional latrines and urine buckets meant that having the toilet outside the house was more hygienic. But this spatial arrangement also made the toilet an important meeting-place for members of the family.

Huang Sheng-yuan thought there was no need to change this kind of "natural" public space, and to respect the clients' lifestyle he immediately agreed that the new house should not have en-suite bathrooms. What made Mother Yu happiest about this was not only that she would save the cost of installing the bathrooms en-suite, but also that later maintenance of the pipework would be less troublesome.

The farmhouse designed by Chien Hsueh-yi is divided into two parts: one for taking care of the elderly members of the family, and another for holiday and leisure use. The stepped roof of the guesthouse section echoes the shape of the nearby mountains. The conical structure houses a bathing pool which is open to the sky.

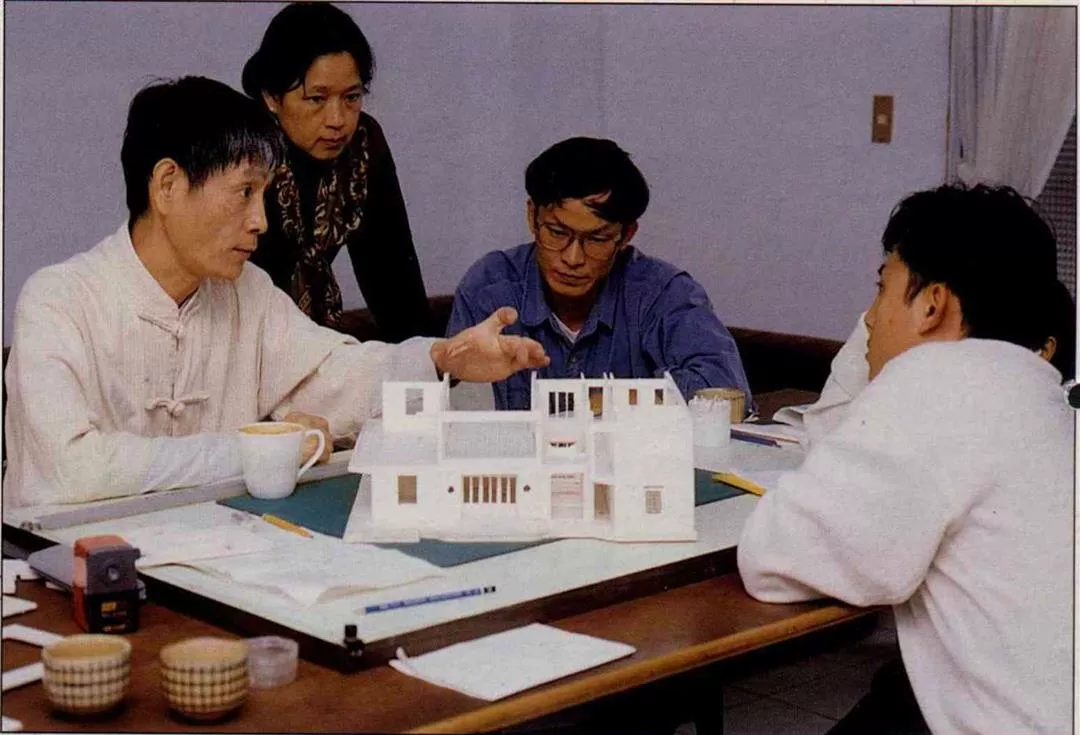

The scale model in the ancestral altar room

After several consultations, the house which Huang Sheng-yuan designed combines a traditional sloping-roofed courtyard dwelling with a two-storey concrete house in the square box style. "This echoes the style of existing residences in the Lanyang area." To meet Mother Yu's requirement of easy access on all sides, the house has a total of seven outside doorways.

Huang Sheng-yuan had thought that his own main ideas for the design, such as the many semi-outdoor areas around the house for people to linger or chat, the sloping roofs, the use of the terrazzo-type floors distinctive of the Lanyang area, and the features drawn from traditional building experience such as the heavy wooden protective boards on the eaves and the typhoon shutters on the windows, would fit in well with the family's wishes. But initially Mother Yu clearly had some reservations about this new house, which looked "very different from other people's."

"The first time we looked at the one-hundredth scale model, Mother actually said the new house looked like a 'fish canning factory,'" says Yu Hung-lung with a laugh. This description naturally dampened the spirits of the architect after all his hard work. But after some discussion it was concluded that the reason Mother Yu had this "false impression" was perhaps because the model was so small and was not colored, combined with the visual effect of looking down on it from above When Huang Sheng-yuan remade the model at one-fiftieth scale, and, in accordance with Mother Yu's wishes, pasted up spring couplets in the right places and painted the walls red where they were to be built of bricks, Mother Yu was finally more able to accept the house's appearance.

Yu Hung-lung says that since his family joined the "Ilan Houses" project, he has learned a great deal from the entire process, and it has prompted him to think about the nature of the way we live in general.

He often thinks about how the new house's rice yard will no longer be used for drying rice, but in fact will be used as a car parking space and for visual effect. Thus the question arises of how it should be surfaced. Laying the ubiquitous concrete seems too rough, while using modern grass concrete would make it look like a public car park. So should they use ordinary bricks, or higher-quality ones? And should the trees around the house be acacias and areca palms, or tropical almond? And what emotional ties does he have to these tree species?

Yu Hung-lung says with a laugh that he means to put the model of the finished design of the house in the ancestral altar room of the old house. In this way this family will have the opportunity to see it every day and to realize that after all--just like getting married-"building a house" is by no means a matter to be taken lightly.

On the road to Chen Su-chiu's house, the outline of the "Four Peaks" is always in view.

When architect meets star-studded sky...

Compared with the Yus, Chen Su-chiu, another prospective house-builder whose site lies at the foot of a mountain in Yuanshan Rural Township, communicated very smoothly with her architect. "What the architect designed was exactly what we dreamed of," says Chen.

Chen Su-chiu is a middle school teacher. The idea to build a house came from her husband Mr. Chang, the eldest son of his family. The Changs' site, which is near their old house, is a field with a loofah plot in front and a starfruit orchard behind, and three watercourses running through it As one approaches the site, from far off one hears the babble of running water, and looking up one sees ridge upon green ridge of the Four Peaks, an outlying branch of the Hsuehshan mountain range. At around 50 meters above sea level, the site lies slightly above the Lanyang Plain, and looking down one can see its broad expanse. The site itself reproduces several features of the plain: "It has plains, mountains and water."

The Changs had two expectations for their new house. Firstly, it should be a traditional family home in which they could look after their parents in their old age. Secondly-and this was the main reason for building a new house-it should have space for the family's second and third generations, who work or study elsewhere, to return home at holidays. In between times it can be used as a guesthouse for holidaymakers.

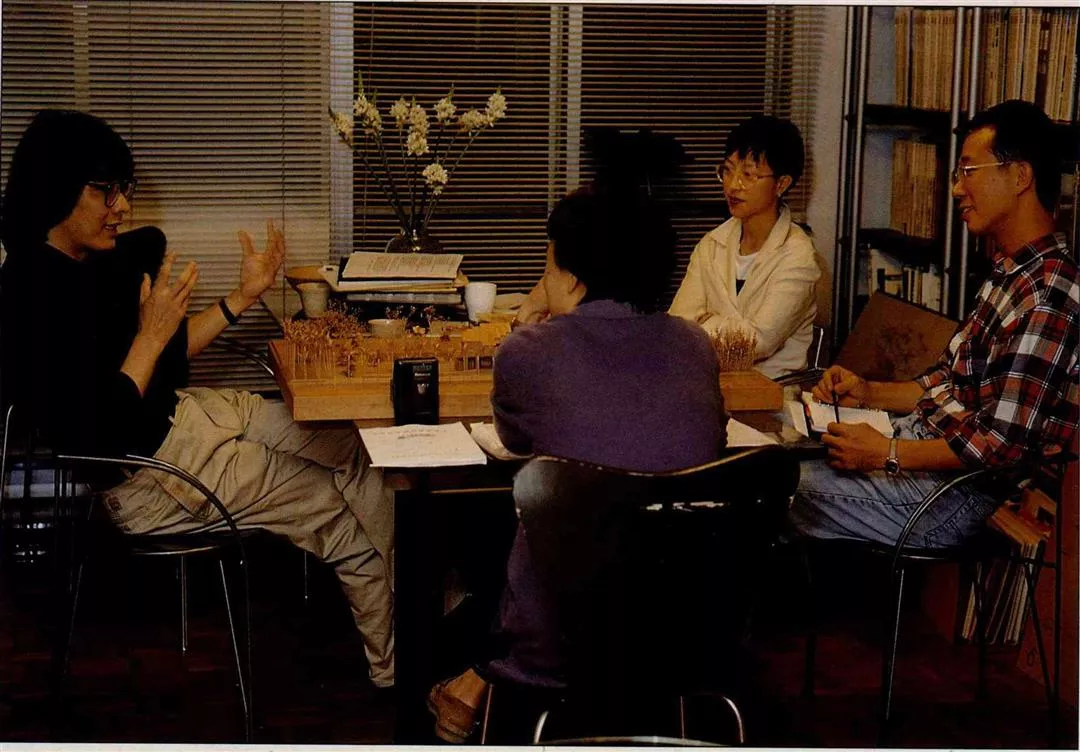

The architect who designed the Changs' house is Chien Hsueh-yi of Chu-chien architects' office. His first meeting with the family is described as vividly as a painting by Chen Su-chiu, who studied fine art.

It was the season when the starfruits ripen. When Chien Hsueh-yi arrived it was close to midnight, and everyone walked to the site together. Standing on a bank between two fields, seeing the sparkling lights of the Lanyang Plain below and the stars shining in the sky above, and hearing the sound of the wind, the water and insects echoing across the fields, the architect and the owners all exclaimed in their hearts: "How beautiful!" "That night was the first time I felt I was not using my vision, but rather my hearing, my sense of smell, every pore in my body and my breathing to feel nature," says Chen Su-chiu. Chien Hsueh-yi, who has been working in Taipei for many years, admits that this was "the first time" he had sensed Ilan so closely and so deeply.

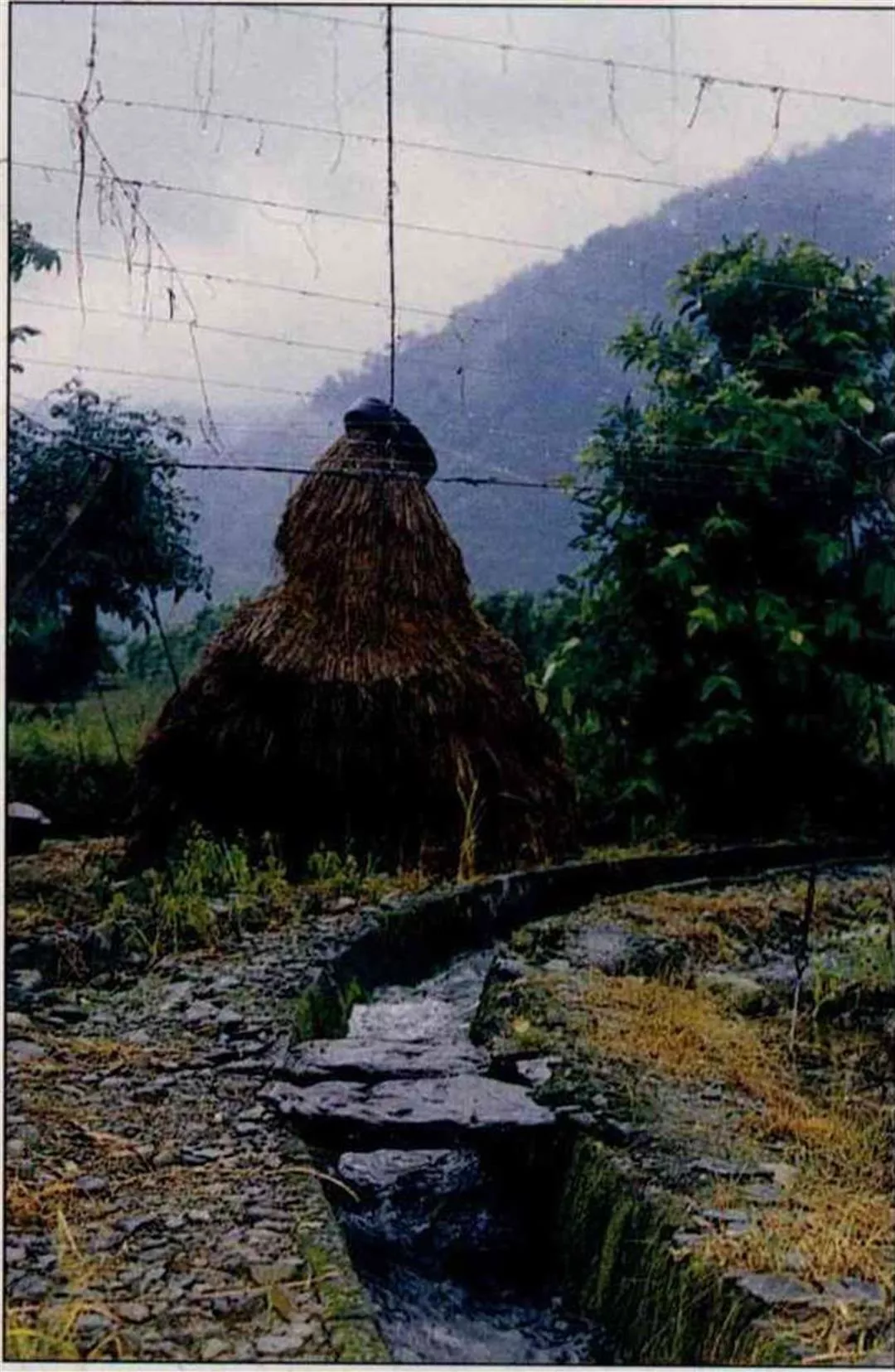

Rice straw can be used as fuel, to shade crops, and in many other ways; the slabs used to bridge the stream between the fields are of local stone. This typical country scene is in Chen Su-chiu's orchard.

Country hospitality

One of the main features of the house's design is a bathing pool in the outdoor area, in a conical enclosure which is open to the sky. "This has its origins in the amazement I felt on the first day at the site, seeing the sky full of stars," says Chien Hsueh- yi. He also designed the whole of the ground floor of the guesthouse section as bathrooms. "This idea comes from Ilan people's habit of bathing in hot springs," explains Chen Su-chiu.

Chien Hsueh-yi says he tried to incorporate people's feelings for nature into the building. For instance, the stepped sloping roofs echo the shape of the nearby Four Peaks mountains. The four bedrooms in the guesthouse section are all on the second floor. They have floor-to-ceiling sliding glass doors, because "we wanted as much of nature as possible to be visible," says An Yu-chien, who is also one of the main designers of the project.

"Throughout the design process," she says, "what impressed me most was the feeling that the clients were not in a hurry to build a house just for today, but that it was something they wanted to be passed down through the generations of their descendants. Just as Mrs Chang often says, this beautiful scenery is not ours alone. She hopes that by running a guesthouse the family can also have a strong sense of sharing with everyone." Of course they also see the guesthouse as a source of income,but perhaps apart from this there is an element of country hospitality!

"You have to see Ilan in the rain to appreciate it properly," says Chen Su-chiu. The site for the Chang family house, designed by Chien Hsueh-yi, lies between a vegetable plot and a starfruit orchard. The view from it is acknowledged as one of the most beautiful of all the sites.

A dream of nature comes true

For a client like Chen Su-chiu, this "house-building dream" expresses the longing and efforts of the generation of villagers now in the prime of life, who no longer practice farming, to be close to nature and the land. For the convenience of their work and their children's schooling, Chen Su-chiu and her husband do not currently live in their family's old home, but in Ilan City. They only return home at weekends and holidays, to climb the hills with Chen's father-in-law and be close to the land. Chen Su-chiu, who paints, says that in fact building the new house is also part of the realization of her "dream of nature."

"Whenever I come to the orchard, the birds fly away when they see me. It's not like Uncle Ah-fu [an employee who looks after the orchard and vegetable garden at the Changs' site]. The birds aren't the least bit afraid of him, and he too seems to be the birds' friend-he knows which birds built which nest and laid which eggs. He is at one with the land. I'm sure that when our new house is built and I come and stay here often so that I'm close to nature night and day, then it will be possible for me to be like Uncle Ah-fu. Nature is like that. If only you care about it and put in love, the flowers and plants will be beautiful, and the birds will come....," says Chen Su-chiu.

Among the different "Ilan Houses" projects, that of Chung Chi-tian of Wuchieh Rural Township is a special one. The house he dreams of must both serve religious needs as a temple, and be a home for three generations. The architect working with him is Wang Chen-hua, who is well known for his research into courtyard-style houses.

The Chung family are devout followers of I-kuan Tao (a religion which combines elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism and other faiths). Two generations of the family live together. The father is a "Representative of the Great Teacher" (a type of Ikuan Tao priest), and has been working in the service of his religion for many years. His reason for building a new house is that he wants to build a place of worship, "to give fellow believers who come from far away a comfortable temple to stay in." Mother Chung says this has been the whole family's wish for many years.

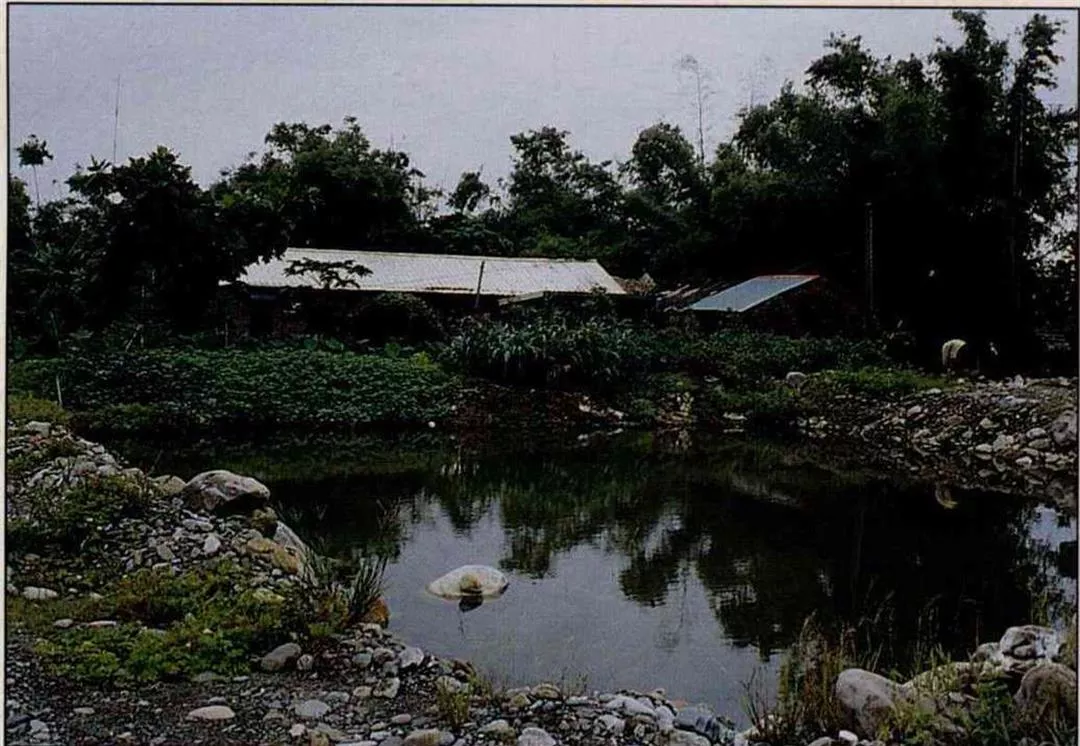

The Chungs' old house stands to the rear of the site for the new one. Still unlevelled, the site looks like a pond. Behind the hedge is the family's vegetable garden.

Combining Heaven, Earth and man

Apart from Chung Chi-tian, the father of the family, the member of the Chung family most involved in designing the new house has been his second son Chung Hsing-tao. Every time Wang Chen-hua discussed the design with his father, Chung Hsing-tao would be beside them listening.

In a notebook he jotted down some of his ideas for the future house: "Space to be arranged for old people's living requirements for the next 10 years, e.g., need for unrestricted movement." "Family continuity, adaptability to future changes in family size." "A living space for leisure, peace, harmony, comfort, settling down, rest and recuperation." "The determination, simplicity, hardship and indomitability of our pioneering forefathers' character." "Far from the madding crowd." "The feeling of returning home." "The new house should one day become an ancient monument."

In Wang Chen-hua's hands, such expectations were all included in the new house's design, which is based on the spirit of traditional courtyard dwellings. Wang says that the traditional spirit of Chinese buildings includes three elements: Earth, humanity and Heaven. Earth means nature; humanity means human relationships; and Heaven means the process of life. It is only when these three criteria are understood that one can do the design.

In the house Wang Chen-hua has designed for the Chung family, he hopes to preserve the spirit of a traditional courtyard house while meeting the needs of modern living, and to "let each part of the house have its own character and purpose.".

Where there is fire there is vitality

Explaining the design of the new house according to his own understanding, Chung Hsing-tao says that for instance his father had originally wanted to put the ancestral altar room, which is the focus of the "Heaven" element, upstairs, but Mr.Wang suggested: "The altar should go on the ground floor, so that both generations in the house see it every day and feel close to their ancestors." When the family heard this suggestion they thought it was very well founded, so they accepted it.

Apart from the position of the ancestral altar room, the way the dining room is joined with the kitchen is also central to the spirit of the whole house's design. In Wang's view, "where there is a fire there is human warmth, and vitality." Thus the dining room and the kitchen are joined together and closely interact. "To use the dining room just for eating in would be a waste," says Wang: such activities as children doing their homework or family members chatting can all take place there. Described this way it is an organic space which can be used flexibly. The Chung family also unanimously accepted this suggestion. The dining room and kitchen are also spatially linked with Mr. and Mrs. Chang's bedroom, to create a "triangle" which is the core of the whole home.

As for the temple on the second floor, the main feature of its design is its regular rectangular shape. "The whole design stresses brightness; we didn't want any atmosphere of mystery," says Chiu Chuang-yi, who was also involved in designing the house. Much use is also made of outdoor space, as with the glass doors all along the sides. These are not only intended to let in light and air: after praying or listening to teaching for a long time one can also easily step outside at any time to stretch one's limbs and relax one's mind.

In response to the human culture and natural environment of the Lanyang Plain, Wang Chen-hua incorporated many features often seen in old Ilan houses into the Chung home, such as turtle-shell pattern windows, and openings in walls in the shape of peaches and pomegranates, which symbolize good fortune. To cope with the local climate of fierce sunshine and abundant rainfall, the roofs have very broad eaves. In the central courtyard one can watch the rain and listen to its melody.

Where there is fire, there is warmth and vitality. The kitchen is the centerpiece of Wang Chen-hua's design.

Beginning a family heritage

Wang Chen-hua says that in his dialogue with the Chung family, there were many ideas on which they agreed. The Chungs did not want a wall around their house: "If thieves come they can come upstairs to pray," Nor did they want en-suite bathrooms for the bedrooms: instead the toilets should be gathered together in one place. Wang Chen-hua very much favors this idea. "Going to the toilet is the most natural thing in the world, and when you come out you have a happy sense of 'complete relief.' This is an opportunity to meet people naturally, by chance, so why shut everything away in a bedroom for the sake of 'efficiency'?" he asks.

In the process of many discussions and dialogues, what Chung Hsing-tao says impressed him most was that this house-building project has focussed the energies of the whole family. "Every time my younger brothers phone home we discuss all kinds of aspects of the design of the new house." Chung Hsing-tao says that perhaps this is a fine opportunity to think about the direction the whole family should be going in, and even the life plans of family members. "Just as Father often says, building a new house is not only to give us a new shell, but is also the beginning of passing down a family heritage," says Chung Hsing-tao.

If we say that the Chung family approached building their house with a very earnest attitude, the family of Huang Jui-chiang, whose plot lies at the foot of the mountains in Sanhising Rural Township, presents a very different example.

The Chung family are devout followers of I-kuan Tao. The house's temple is the focal point of their faith.

A Kavalan home

Huang Jui-chiang, a teacher at Ilan High School, is general secretary of the Ilan Teachers' Association for the Promotion of Human Rights, and a typical social activist. The site for his new house is in front of the old one, and before the architect's demonstration model was completely finalized, he had already driven his excavator several times to dig a fish pond, plant trees and construct a rockery, and had even built a pavilion in front of the house.

Huang Jui-chiang's architect is Lin Chih-cheng, whose office is in Hsinchu. Like Huang, he is nearly forty, and he wears a beard while Huang sports a moustache. Everyone jokingly said that these two were "fated to be a pair." The Huangs' house is designed in the spirit of creating "a Kavalan home" (the Kavalans were one of the Pingpu or plains aboriginal tribes, and lived on the Lanyang Plain). The architect and the client agreed that to search for Pingpu dwellings' architectural features, which have perhaps already disappeared from Taiwan, was something they both wanted to do.

Huang Jui-chiang believes that when talking about Taiwanese culture one cannot ignore aboriginal culture. Ilan people's style of living is deeply related to the that of the Pingpu. "Their paternal ancestors were Chinese, but not their maternal ancestors," he says: when Han Chinese first came to Taiwan to clear the land for farming, many bachelor pioneers took aboriginal wives, so there are many blood bonds between the Hans and the aboriginals. An aunt of Huang's can still converse in Kavalan, and Huang believes that the virtues inherited from the aboriginals include their aesthetic sense. This is something people today need to seek out.

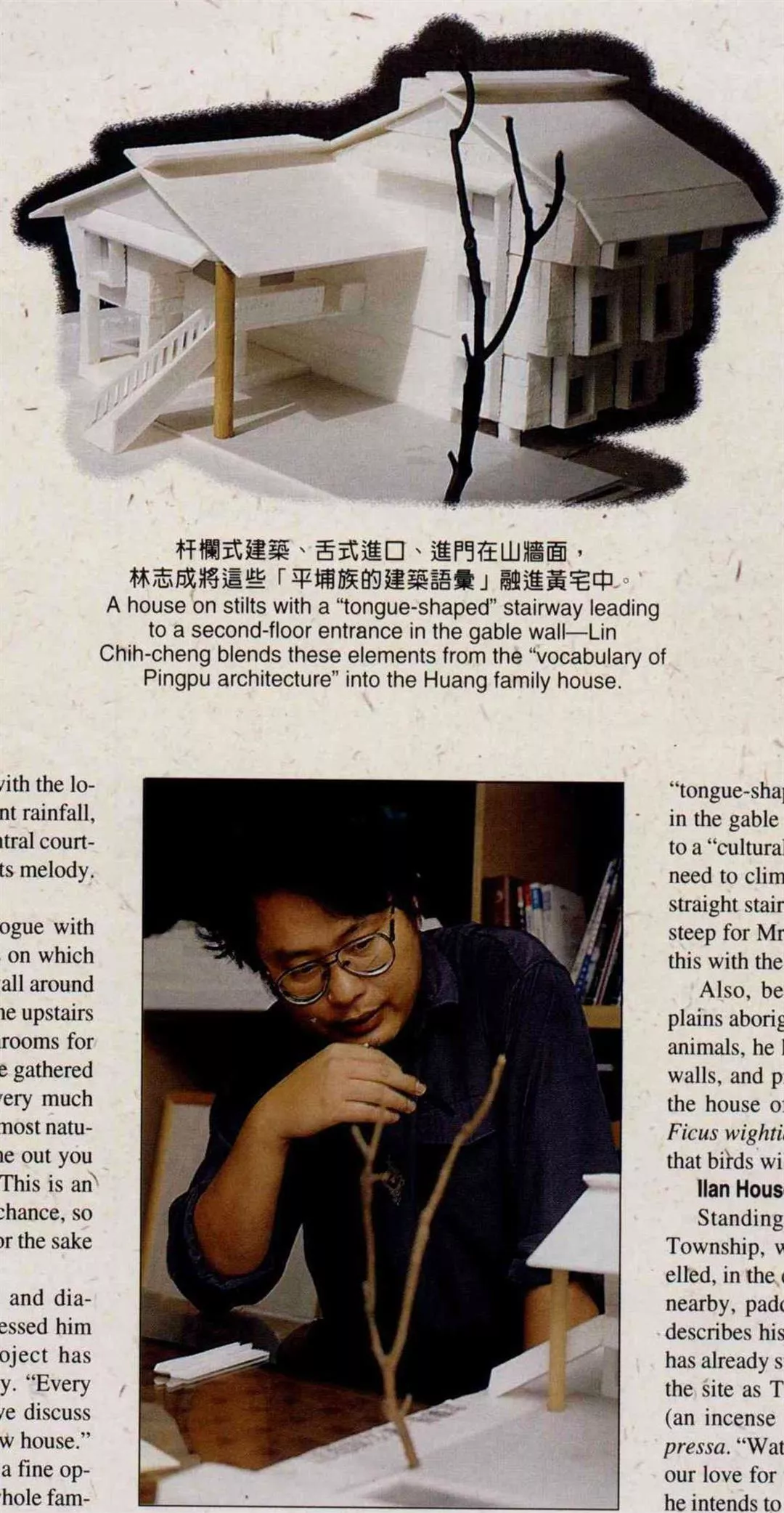

For the design of the Huang house, architect Lin Chih-cheng combed historical records in search of what he feels was the "architectural vocabulary of the Kavalans." For instance, he raises the bottom, of the house up on stilts. "This is a building style the plains aborigines developed to prevent animals, insects and damp air entering the house," he says. For the entrance to this house on stilts, Lin Chih-cheng followed the description in the historical records by creating a "tongue-shaped" staircase leading up to an entrance in the gable wall. Lin believes this may correspond to a "cultural habit"of the Kavalans arising from the need to climb up to enter a house on stilts. But the straight staircase up to the second floor is rather too steep for Mr.Huang, and he is currently discussing this with the architect.

Also, because the architect believes that the plains aboriginals had a very close relationship with animals, he has provided for some holes in the end walls, and proposes to plant some trees in front of the house of species which attract birds, such as Ficus wightiana, the "sparrow banyan," in the hope that birds will come and make their nests there.

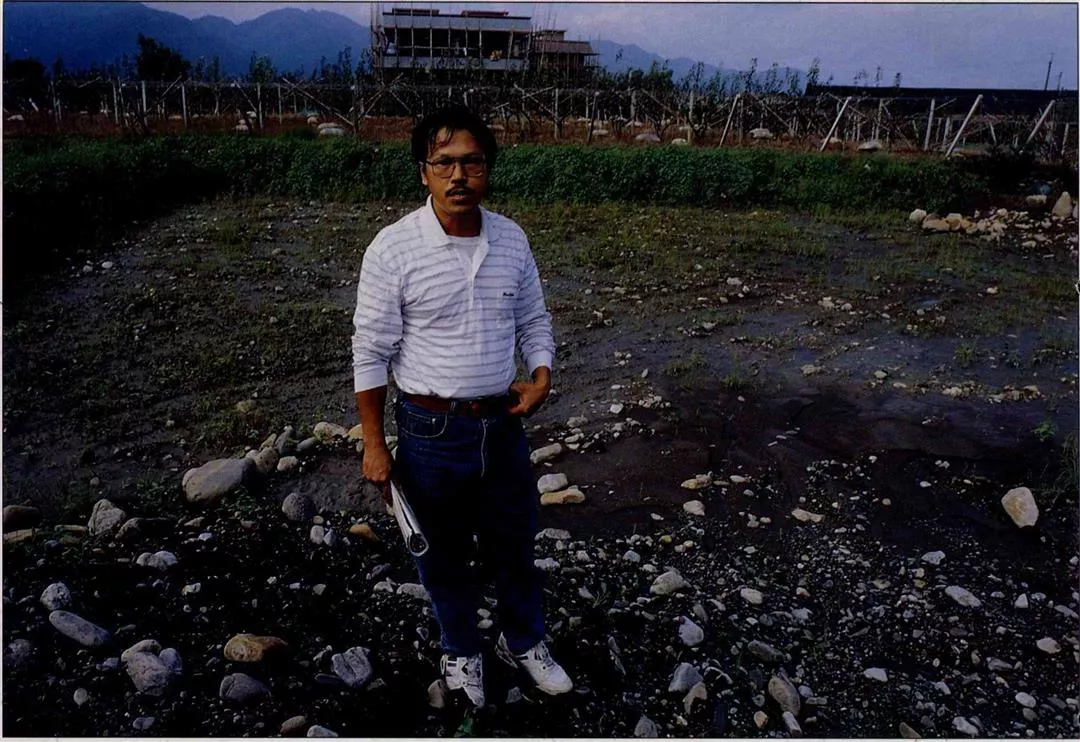

Huang Jui-chiang sees himself as a defender of native culture. He wants to build a "Kavalan home" on his family's land.

Ilan Houses-what's all the fuss about?

Standing on Huang's plot in Sanhsing Rural Township, which has already been filled and levelled, in the distance one sees green mountains, and nearby, paddy fields. Huang Jui-chiang excitedly describes his future new home. He explains that he has already successfully planted such native trees on the site as Taiwan cypress, Calocedrus formosana (an incense cedar), tree ferns and Michelia compressa. "Watching the little trees grow big will build our love for this place," he says. For the fish pond, he intends to divert water from a mountain stream to raise the crucian carp, pond loaches and other native fish which he used to catch as a child. Upstairs in the new house he plans to build a community library for the use of local people, and he has even thought of the inscription for his rockery: "I'll use the characters 'yue guang' ('moonlight'), because that's the name of the village where my old home is, and people here have a boundless affection for it," he says.

The "Ilan Houses" project has been running for l0 months now. "None of the houses have been built yet,but people have already rung asking for the plans, saying they want to copy them to build new houses," says Chen Teng-chin of the Ilan County Government.

Does this mean that the nine Ilan Houses will also become models for farmhouses which will be copied throughout Taiwan without regard to local style and conditions? And just what "Ilan style" do the nine houses, with their very different appearances, actually reveal?

For the nine prospective builders, whether the new "tailor-made" houses into which they have put so much energy will be copied is perhaps not the main point. What is important is that each of them seems to be resolutely pursuing a dream. Huang Jui-chiang's "dream of returning to his native land," old Mother Yu's wish to build a "house with an upstairs," the art teacher's desire to get in touch with nature, lively young people's aspiration to "pass on a family heritage"...: at the end of November, after the plans are finalized, work can start and the fruits of these owners' and architects' joint efforts and dreams will gradually start to become reality.

It would appear that their attitude of making their dreams a real part of their lives, and their serious approach to building their houses, is something even more worth copying. And the mettle Ilan people show in not simply following the crowd, but having the courage to make their dreams come true, is surely the most inspiring "Ilan style"!

A house on stilts with a "tongue-shaped" stairway leading to a second-floor entrance in the gable wall-Lin Chih-cheng blends these elements from the "vocabulary of Pingpu architecture" into the Huang family house.

At Liuliushe by the Tungshan River stands a tropical almond tree which was planted a century ago by Dr.George Mackay of Tanshui. Many old people in Liuliushe can still speak Pingpu.

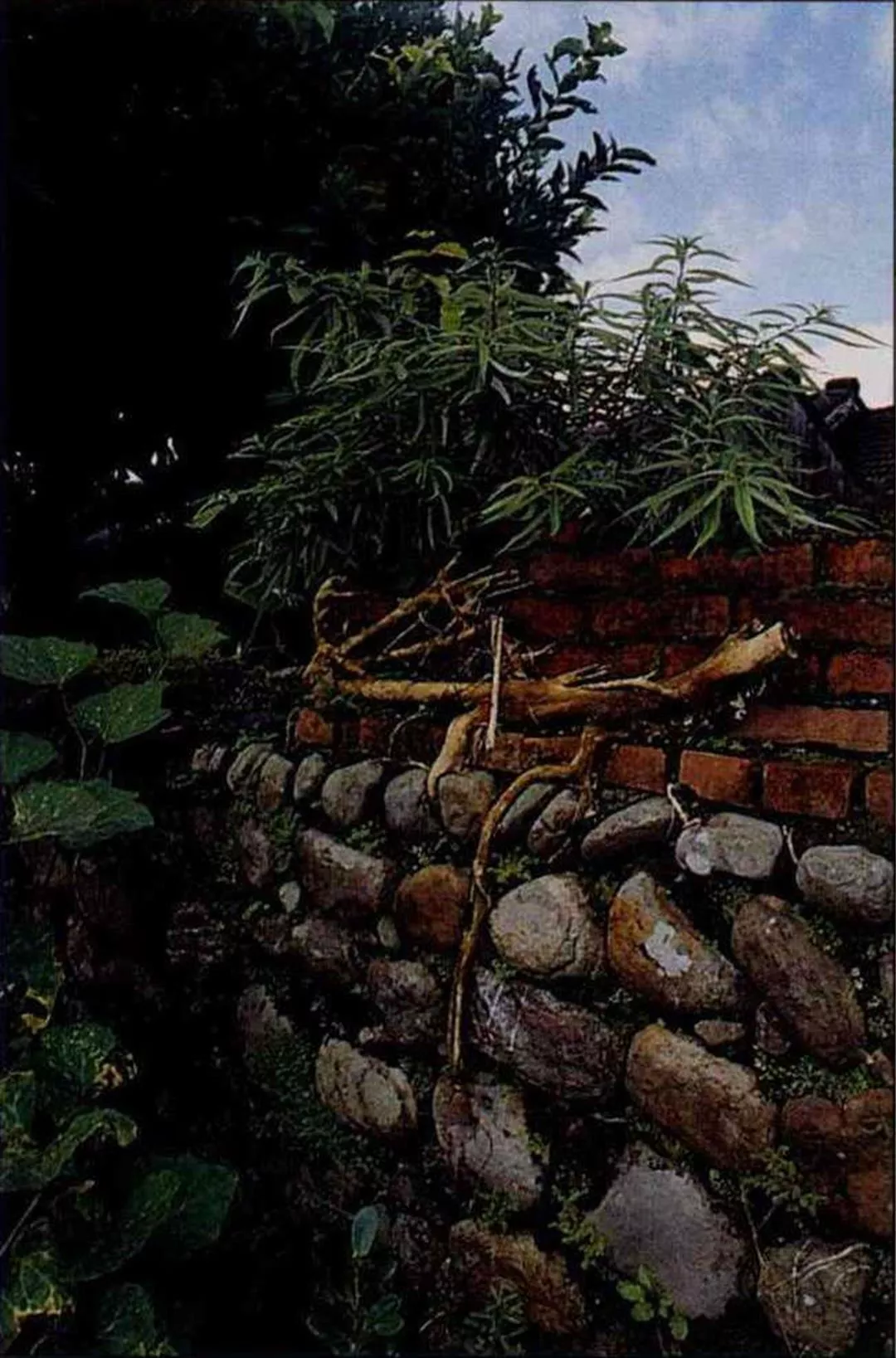

Huang Jui-chiang's old house is to the rear of his building site. The house is almost a century old and is still surrounded by an ancient wall. Gun holes in the wall are a reminder of the clashes between Han Chinese and local aboriginals in years gone by.

Fallen seeds from under the tropical almond tree at Liuliushe.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)