if there hadn't been a DongChen-liang for these past ten years, Kinmen would have been a much less interesting place." So says Yang Shu-ching, chief editor of Kinmen Studies, an ongoing research series on the history and culture of Kinmen.

Dong Chen-liang filmed his first documentary in 1987, and after martial law was lifted in Kinmen in 1992, society there began changing very rapidly. With political change and commercial development crowding out old ways of life, Dong has captured the changing face of Kinmen society over the past decade perhaps as well as anyone through his documentaries and docu-dramas. His subjects have been many, including history, social movements, cross-strait relations, local culture, environmental protection issues, and how it feels to live on the front lines of the decades-old conflict between Taiwan and mainland China.

Dong enjoys enthusiastic support from the local community, which has provided him with generous financial assistance, manpower, filming locations, and more. The quality of his work, moreover, is well recognized; he has received Golden Harvest Awards for Short Film and Video, Golden Ribbon Awards, and China Times Express Film Awards. He has also entered numerous works in major film festivals in Japan, Canada, Australia, and Singapore.

So what exactly has Dong contributed to the history of cinematography in Kinmen? What is so special about his work?

When asked what prompted him to take up a career in filmmaking, Dong recalls that his earliest inspiration came from the outdoor movies that they used to show in all the villages and military camps.

When Dong was a boy there were over 100,000 troops stationed on Kinmen. There was no such thing as television, and the most luxurious entertainment for most people was outdoor movies. Dong and his friends would take shortcuts between the villages to catch whatever movie was playing.

"Almost all the movies were on patriotic military themes, or else they were love stories based on a Chiung Yao novel. Every once in a while there'd be a war movie from Europe or America, but no matter what was playing, we'd be sure to be there watching it," says Dong, who adds that although the movies were captivating, the stories they told were always light years removed from the reality of their daily lives. That is why he later chose to film stories of Kinmen itself. He wanted the people of Kinmen to be able to see their own story on screen.

Dong was such a mischievous kid that it ended up taking him nine years to graduate from elementary school. He was 18 when he finally entered senior high school in Taipei. After graduating from high school and doing his two years of compulsory military service, he happened to get hired as assistant cameraman at an advertising company. He started attending cinematography courses at a documentary workshop during his spare time, and that proved to be the first step toward his career in film.

Birthday Gift for Dad

Dong started off by filming little stories taken from everyday life. In 1988 he filmed Birthday Gift for Dad, which describes the lives of himself and his older sisters and brothers on the main island of Taiwan. He then asked a relative to take the film back to Kinmen and show it to his parents to give them a better picture of how he and his siblings were living.

Dong returned to Kinmen in 1989 at the height of a campaign demanding the repeal of martial law there. His purpose was to record life in Kinmen on film, but filming equipment was not then allowed in Kinmen, and one had to have a license just to use a regular still camera, so he borrowed a camera from his brother, who ran a photo processing shop. He took thousands of photographs and edited them into an unusual documentary entitled The Embarrassment of Going Home. It focused on events surrounding the election campaign of Weng Ming-chih, a Democratic Progressive Party candidate seeking to represent Kinmen in the national legislature. In this work, Dong documents Weng's return from Taiwan to Kinmen to run his campaign, the machinations of entrenched local political forces determined to thwart him, and the cowed silence of the local community.

According to Tseng Ya-lan, an art critic who is intimately familiar with Dong's career, Dong made The Embarrassment of Going Home on a shoestring budget, and he had to deal with myriad restrictions imposed by the martial law authorities. As a result, the footage obtained while working on that documentary later got used in several other films. Indeed, much of Dong's style has evolved out of a need for penny-pinching. When he has been able to get all the footage needed for a complete story, he has made documentaries. When it has been impossible to get all the needed historical footage, he has filled in the gaps with dramatized sequences and released docu-dramas. No one else can come close to matching the amount of documentary footage on Kinmen that has been amassed by Dong's Firefly Image Company. Says Tseng, "You could think of it as a very comprehensive archive of historical film footage on Kinmen."

Tough conditions, however, have just brought out the best in Dong. In 1993 he completed The Bombardment, in which he interviewed old-timers who told the story of the shelling of Kinmen by mainland China in 1958 in the Battle of the Taiwan Strait. In 1995 he filmed Every Odd Numbered Day, which tells the suffering of the local populace as mainland China shelled Kinmen every other day for more than 20 years after the Battle of the Taiwan Strait. In 1995 he also completed Straight Ahead with a Rifle, which details the impact of military firing ranges upon the safety of local communities. In 1997, The Lions of Good Fortune focused on the lion statues that people in Kinmen use to ward off evil spirits and misfortune. In that same year he also filmed Homesick 2000 Meters, which describes the dilemma of women from the city of Xiamen who marry men in Kinmen. Although Kinmen is separated from Xiamen by just a few nautical miles, the standoff between Taiwan and the PRC means that the only legal way to get from Xiamen to Kinmen is to fly first to Hong Kong and then Taipei before finally heading from there to Kinmen. The trip takes two days even though residents can gaze across the water to the city on the opposite shore. Last year Dong completed Black Name, which tells the story of Chen Chen-chien and the blacklist maintained by immigration authorities in Kinmen during the martial law period. Chen was one of those put on the blacklist and prevented from returning to Kinmen. He eventually forged false documents and sneaked back in, but he was soon arrested and thrown in prison.

Images from the battlefield

Dong Chen-liang has slowly developed a style of his own over the years.

Tseng Ya-liang notes that Dong's cinematic style has been greatly influenced by prevailing trends in the Taiwanese movie industry during the 1990s, when he was developing as a filmmaker. Dong uses a lot of empty scenes, for example, in which no people appear. His work is also characterized by slow pacing and a subdued atmosphere. "That kind of style in a documentary can easily bore the viewers," says Tseng, "but Dong's skillful repetition of the main themes gradually lends a certain emotional hue to his works that really strikes a chord."

In the view of movie critic Tseng Chuang-hsiang, Dong very successfully conveys the unique atmosphere of Kinmen with his images of old-style farmhouses, good-luck lion statues, and the ubiquitous signs of military presence to be found everywhere in the countryside-concrete pillboxes, army bases, bomb shelters, patriotic slogans painted on walls, etc. He illustrates his point by mentioning Straight Ahead with a Rifle, in which Dong continually returns to the image of a bombing range, communicating how it feels to live next to such a place. It is a factor always on the minds of local residents. This repeated use of a single image is a very unusual technique, but it doesn't bore the viewer; on the contrary, it leaves one feeling that he has gained new insight into the subject of the documentary.

Tseng points to Every Odd Numbered Day as another case in point. This film returns time and again to images of patriotic slogans on local walls, highlighting the helpless feeling of knowing that the island one calls home has been chosen to serve as a battlefield. Homesick 2000 Meters shows how near the cities of Kinmen and Xiamen are across the water, yet how far apart their residents live due to political reality. The empty scenes in this documentary highlight the longing for home of a people cut off from their roots.

Dong likes to tell stories with images, and points as an example to his just-completed Black Name. Almost all the scenes show abandoned pillboxes and bomb shelters, which he deliberately fits out to look like prison cells. One of his purposes in so doing is to convey a feeling for the numbing fear of the martial law period. The other purpose is to express the mood of the blacklisted Chen Chen-chien, for whom being barred from his native Kinmen was like being cast into a world without sunshine.

Purse from a sow's ear

As a native of Kinmen, Dong knows how to get his compatriots talking freely in front of the camera, and his role as a participant in his own documentaries adds to the persuasiveness of his films. Moreover, because he has never had enough money to hire many actors, he has had no choice but to appear quite frequently in front of his own cameras. This is another distinguishing feature of his work.

A lack of funds inevitably affects quality, of course. The writer Chen Ying-chen once wrote in critiquing a Dong film that the director's imagery and logic demonstrated a rare degree of precision and sincerity, but the recording, photography, and editing were all somewhat rough.

Dong himself is quick to admit that a lack of funds is one of the biggest problems that he faces as a filmmaker. To film Every Odd Numbered Day, his most expensive work thus far, he borrowed far and wide from supporters in Kinmen, yet was only able to come up with about NT$2 million (about US$65,000). He was only able to complete the film by renting lighting equipment at reduced rates from an acquaintance and getting a well-known singer from Kinmen to compose the soundtrack free of charge. According to Dong, his main sources of funding are the Government Information Office, the National Culture and Arts Foundation, and supporters in Kinmen.

"I use filmmaking as a vehicle for expressing my deep affection for Kinmen, and I use that same affection to lend a deeper content to my films," says Dong, adding that he will continue making films no matter difficult circumstances may be.

p.32

Noted filmmaker Dong Chen-liang, who hails from Kinmen, uses abundant imagery to re-create the unique atmosphere of the island

he calls home.

p.34

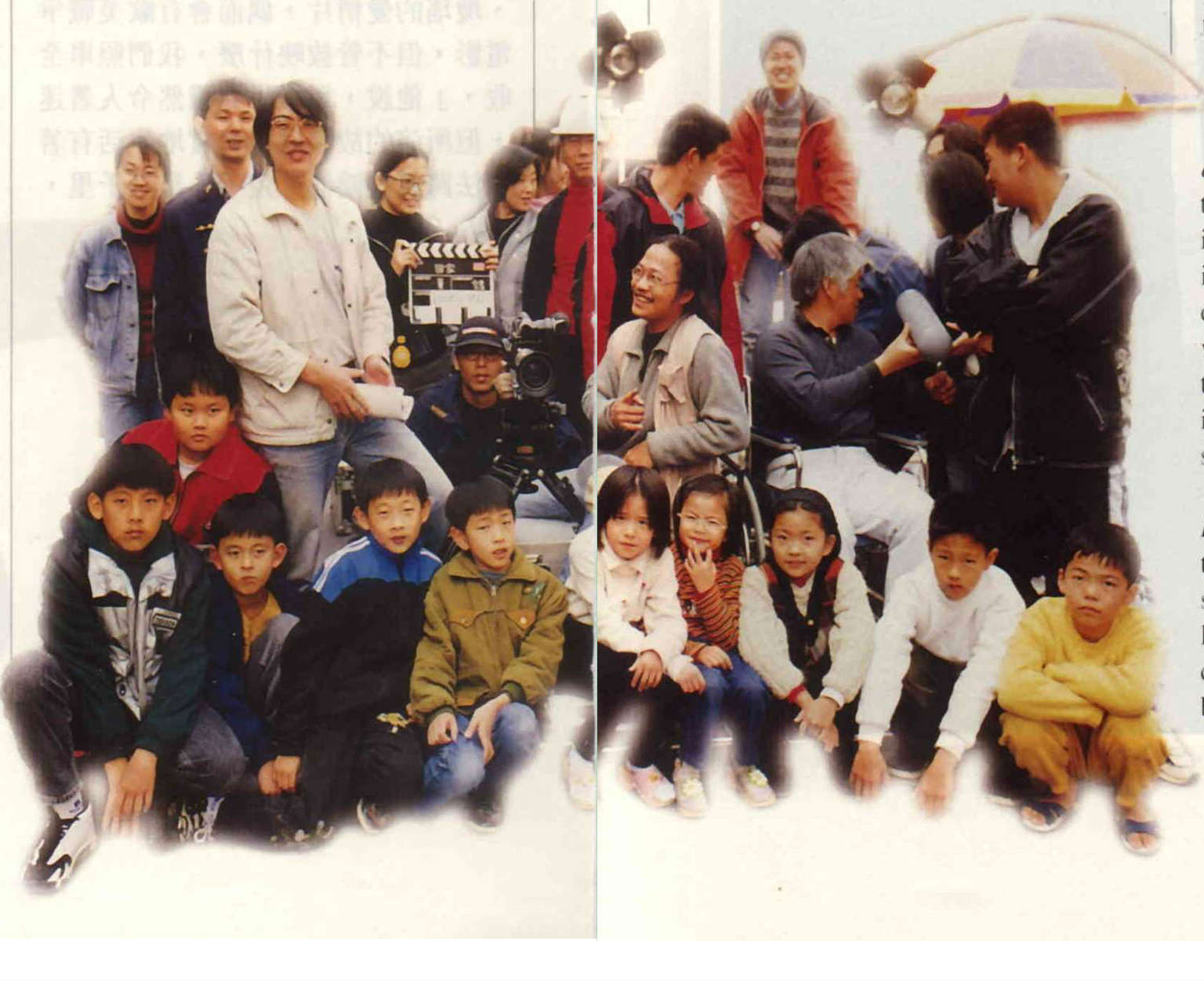

Dong has always operated on a tight budget, and has relied heavily on generous donations from Kinmen residents to make ends meet.

Dong has always operated on a tight budget, and has relied heavily on generous donations from Kinmen residents to make ends meet.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)