Fenglin: A Rift Valley Hakka Township

Kaya Huang / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Scott Williams

July 2008

Fenglin isn't decked out in neon, nor is it home to any of the world's tallest skyscrapers. But the "till the fields when the sun shines and study when it rains" mentality of the rural township's Hakka residents and the devotion of a previous generation of migrants to developing local educational and healthcare systems, have made Fenglin an incredibly refined rural community.

At 8 a.m the sun is already shining brightly. Elderly residents can be heard singing Hakka folk songs in the distance. There is a shyness in their voices, but also something of a child's pure attachment to the land. When we look up from Fenglin's main artery, Kuanghua Road, the Central Mountain Range is right before our eyes. We climb on a bike to negotiate streets laid out in a grid pattern by the Japanese. Save for the occasional cries of hawkers from the roadside morning market, there is little noise other than the hum of insects, the chirp of birds and the barking of dogs. It's so quiet in fact that we can't help but wonder where all the people have gone.

As this thought goes through our minds, a gray-haired senior citizen drives slowly past, making his unhurried way down the street on an electric scooter. The casual pace of the vehicle and the general silence compel even visitors such as ourselves to slow down a bit.

"There's more to these seniors cruising around on their scooters and bikes than you might think," says Reverend Chen Ming-hui, the pastor assigned to Fenglin's church for most of the last year. "Ask any of them. They're all over 80 years old." According to Chen, 20% of Fenglin's population is over age 65, and 72 residents are over 90. It turns out that the township is more aged and has experienced more outbound migration of young people than any other in Taiwan.

"At its peak in the 1960s, Fenglin's population reached 30,000. At the end of February 2008, it was just 12,459," says 55-year-old Liu Ching-sung, a secretary with the Fenglin Township Office, explaining the quiet and emptiness.

The silent streets of the township retain a strong Hakka flavor as evidenced by the fucai (pickled mustard greens representing longevity) hanging from bamboo poles outside of every home.

Fenglin streets against a backdrop of mountains.

Hakka "double immigrants"

Fenglin's residents begin planting their mustard greens in mid-August, and harvest about two months later. Steeped in salt then partially sun dried, the greens become the tasty fucai of Hakka cuisine. Fully dried, they make another Hakka specialty-meigancai. Fucai, the more delicately flavored of the two, is used in soups, whereas meigancai gives savor to stewed meats. Hakka cuisine's frequent use of pickled vegetables is emblematic of the culture's industriousness and thrift.

Passing through alleys heavy with the salty-sour scent of the preserved vegetable, we soon come to the township's busiest street-Chungcheng Road. The sweet smell of shredded daikon wafts towards us from Pengchi, a shop specializing in Hakka vegetable buns that stands opposite the township's only 7-Eleven. The fat round buns, made from glutinous-rice dough filled with veggies, are a Hakka breakfast staple. Pengchi's owner gets up at 4 a.m. every morning to prepare them for her customers.

Pengchi begins selling its buns at 5:30 a.m. Though they cost NT$5 more than ordinary vegetable buns, the shop invariably sells out by 10 a.m. Pengchi's many varieties of steamed glutinous rice cakes are also popular with customers. The buns and cakes are authentically Hakka-the outsides have a texture like firm gelatin, the fillings are plentiful, and the daikon is seasoned with salt and dried shrimp. Visitors and returning natives all highly recommend the food.

The area produces the many varieties of preserved mustard greens for which the Hakka are famous, including fucai, meigancai, and Hakka "sauerkraut."

The warmth of the flues

The flavors of the local Hakka cuisine recall the history of the eastern Hakka's movements and development of new lands. The tobacco barns that litter the township, on the other hand, are visceral reminders of how early Fenglin residents made their livings and of the "immigrant" industries of the Japanese occupation.

Soon after Taiwan was ceded to Japan at the end of the first Sino-Japanese War in 1895, the eastern part of the island became the target of Japanese immigration and development. This immigration came in three waves. The first was driven by private-sector organizations such as Kata Kinzaburo's "Kata Group." The second, from 1906 to 1917, was government sponsored and involved large numbers of immigrants from the main islands of Japan, which were suffering population pressure and rice shortages. For the third, which got under way in 1921, the colonial government brought in Taiwanese farmers to develop tobacco, tea and sugarcane industries.

The Taiwanese who migrated from western Taiwan to the east coast between 1906 and 1930 (called "double immigrants," as their ancestors had previously migrated to Taiwan from the Chinese mainland) were largely from the prefectures of Taihoku (modern Taipei City and County, Keelung, and Ilan County) and Shinchiku (Hsinchu, Miaoli, and Taoyuan Counties), with Hakka from Shinchiku making up the majority. The area's diverse ethnic terrain also included Japanese, Minnanese, and Aborigines.

The colonial economy was organized principally to meet the needs of the colonizers. Taiwan, which didn't produce tobacco and where few people smoked, became a tobacco exporter to meet Japanese demand for the leaf. According to Hsu Ying-fu, a former employee of the Taiwan Tobacco and Wine Monopoly Bureau, the Japanese began planting a gold leaf variety of American tobacco into the Hualien-Taitung region in 1913. Fenglin became involved with the tobacco industry in 1917, when cultivation of the plant spread to the "immigrant" villages of Fengtien and Lintien.

"In the old days, you could tell how poor or wealthy a family was by the number of tobacco barns on their property," says Hsu. Fenglin was once an important Eastern Rift Valley tobacco grower, and at its height had about 80 tobacco barns for curing its crop. Tobacco, all of which was exported, was the area's economic lifeblood.

In those days, Fenglin's industrious farmers used the period before the rice harvest to sprout their tobacco seedlings. These were transplanted to the fields once they brought their rice in. Generally speaking, when the tobacco reached about head high, its leaves were large enough to harvest and cure.

Once they had picked the green leaves, the farmers strung them in bunches, hung them from bamboo poles, then placed them into their barns. There they were flue-cured, a process which would, over the course of a week, turn the leaves a golden brown. Curing was grueling work. To keep barn temperatures constant throughout the process-necessary if the grower was to produce high-quality tobacco-the grower and his family had to take turns night and day making sure the fire was always lit, but never too hot.

"Some people say the heat from the flues affected the Hakka's quality of life," says Tai Kuo-chen, "and that was really the case." Tai, a second-generation Fenglin resident who was once the principal of Taipei's Nanhu High School, says that while curing tobacco was a sweaty business in the summer, the curing barns kept away the winter cold. Clearly, the business offered upsides and downsides to the Hakkas who came east.

Seen from the recently opened highway bypass, Fenglin's barns look like little houses set atop roof ridges. Now that the tobacco industry has largely relocated, few of the barns are still in use. Here in Fenglin, only Yang Chun-hsiung and Hsu Ying-fu remain in the curing business, and they, like their counterparts in other locales, have replaced their barns with computer-controlled curing rooms. These have cut curing times, eliminated the need for family members to take turns keeping watch, and spelled the end for the tendrils of white smoke that used to hang about the flues. Standing in front of his family's barn, the 70-something Hsu describes Fenglin's former prosperity with a certain detachment, but his eyes can't mask his feelings about the decline of the local industry.

In recent years, the cultivation of China Baby watermelons along the banks of the Hualien River has arisen as a new driver of the Fenglin economy.

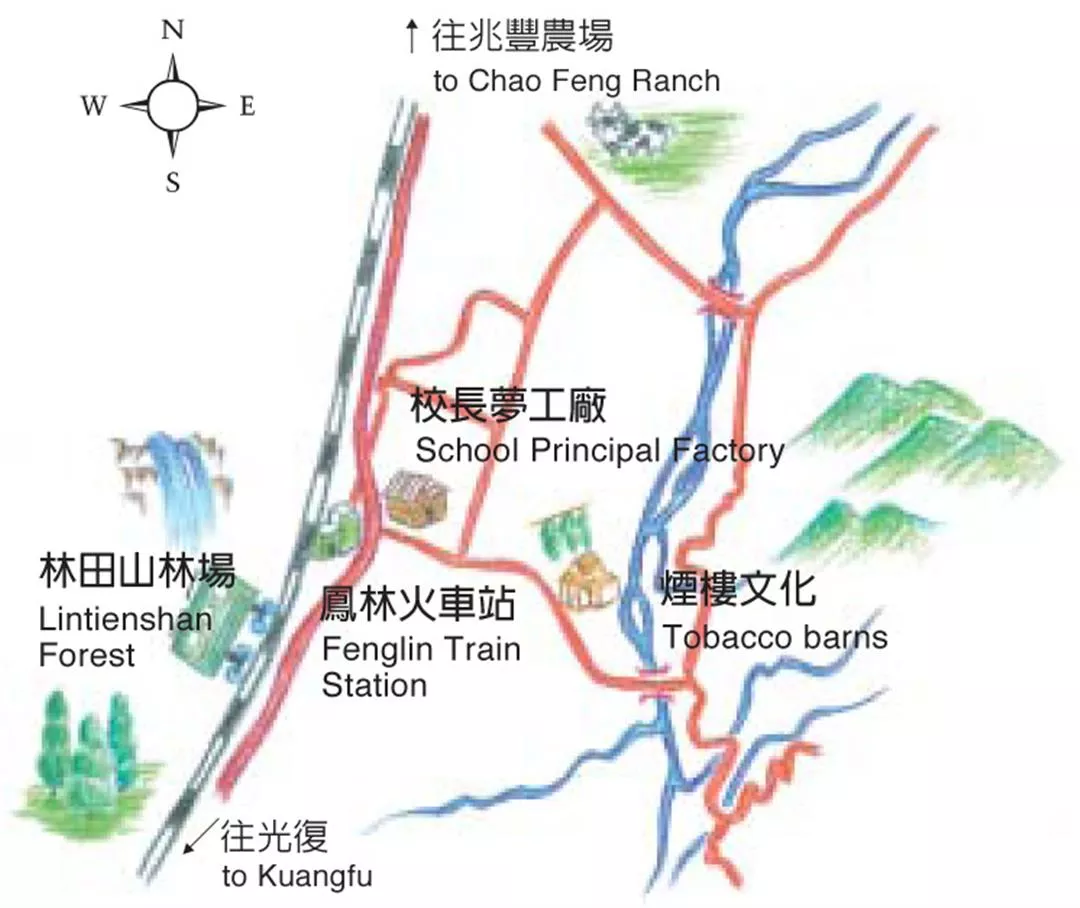

A present-day tourist attraction

Fenglin's tobacco barns are concentrated in three immigrant communities established by the Japanese-Tajung First Village (13 barns), Tajung Second Village (18 barns) and Peilin Third Village (17 barns). These villages possess the best-preserved and densest concentrations of barns in Taiwan today, giving the township a tourist attraction on a par with that of another well known Hakka community-Kaohsiung's Meinung. To prevent the area's history as a tobacco producer and immigrant community from being forgotten, the township is now pursuing plans to renovate and preserve its tobacco barns.

"The tobacco barns are a unique sight," says township chief Lin Ting-kuang, "and should become an interesting tourist draw." Unfortunately, the bypass opened in 2004 just as word about the barns was beginning to get out. The sight of vacationers driving past on their way to Taitung's Hoya Resort dashed township residents' hopes for the future.

Faced with the prospect of Fenglin fading away to nothing, Lin, a third-generation Hakka immigrant who is serving his second successive term as township chief, racked his brains for a solution.

"The Fenglin Township administration now plans to repurpose unused spaces," says Lin, describing the township's approach to revitalization. "Peilin Third Village sits near Provincial Highway 9, a major Hualien thoroughfare, and offers the kind of broad vistas and a pastoral atmosphere that could be developed into a tourism resource. The township administration also approved a five-year development plan for a resort and conference center in Changchiao Borough in late April. We expect the plan, which employs private investment via a BOT model to develop the tourism industry, to create 500 jobs."

It doesn't rain often in Fenglin, and the plentiful sunlight produces meaty, brightly colored chilies. It's no wonder then that Fenglin introduced peeled pickled chilies to Taiwan.

Watermelon bonanza

With the tobacco industry in decline, Fenglin's agricultural future may be in watermelons. The township has nearly 500 hectares along the Hualien River planted in the fruit. The NT$150 million that the watermelon industry generates means a lot to Fenglin, a small township that only receives about NT$130 million from the central government every year.

"All last May, fruit brokers were buying whole fields of watermelon at record prices of NT$180 per vine," says melon farmer Liang Teng-huan, recalling last year's bumper crop and frenzied buying. "They were loading up 15-ton trucks with 600 melons each and driving them out of Chunghsinpu one after another. The farmers' profits averaged 40% or more."

"Fenglin's growers graft watermelon vines onto more vigorous pumpkin roots," says Hsu Hsiu-chih, head of the extension unit at Fenglin Farmers' Association. "The pumpkin roots go deeper than those of the watermelons grown in Chiayi and Tainan, producing a better melon. The sand washed down by the unpolluted Hualien River also makes exceptionally good soil, giving Fenglin's melons their sweetness and juiciness."

Fenglin grows its "China Baby" variety of watermelons on the floodplains of the Wanli River at Chunghsingpu. These melons are long ovoids weighing 12-17 kilos with rinds of light green striped with darker green, and bright red flesh. Fenglin also has 15 hectares in yellow watermelons and 30 hectares in seedless watermelons. The township's exports of its seedless watermelons to Hong Kong, which began in 1972, soon earned Taiwan a reputation as a top producer.

"Unfortunately, seedless watermelons require expensive hand pollination, and cultivation largely came to a halt in 1996," says Liang. "These days, very few are grown." However, over the last two years Fengjung Farmers' Association has begun providing guidance on growing the fruit, and farmers are again producing them in small volumes. Consumer response has been very positive, suggesting that Fenglin's seedless watermelons are just as good as their reputation.

When Fenglin's tobacco industry was at its peak, there was "a tobacco barn every three steps and smoke billowing every five." Many of these barns still remain (right). The tobacco industry has since moved on. These days, only two Fenglin families are still in the tobacco curing business.

Movement and stillness

As we return to Fenglin Township from the banks of the Hualien River, the sweet scent of melons is replaced by the clean fragrance of rice straw, but the tranquil atmosphere remains.

"There aren't a lot of job opportunities in farming communities," says Tai Kuo-chen's wife, who, like her husband, came back to Fenglin to retire after a career in education in Taipei. "The kids go to college in western Taiwan, then stay there to work once they graduate. Fenglin's household registers may put our population at more than 12,000, but only 8,000-some people actually live in the township. It's very quiet here. In fact, Fenglin would be a great place for a retirement community. Hualien's Tzu Chi General Hospital is only 45 minutes away. But it sometimes feels too quiet."

"In addition to people moving away, Fenglin is also facing issues related to its foreign spouses," says Rev. Chen. "Today one in four of its children are the product of a mixed-nationality marriage. The cultural divide in these marriages often leads to educational problems for the kids. Not to mention that Hualien and Taitung have always had fewer educational resources than western Taiwan, and that most of these families are also socioeconomically disadvantaged. These are real obstacles to the region's future development," continues Chen, who has authored a plan to use non-profits and elementary schools to provide counseling and assistance for children from low- and middle-income families, Aboriginal families, mixed marriages, and single parents, and for children being raised by grandparents.

The hills rising up from the gold and white fields of rape are as lovely as ever. The pastoral serenity is momentarily interrupted by the leap of a startled ring-necked pheasant. Time seems to pause and becomes as tranquil as the landscape itself. The little villages scattered amidst this beautiful scene seem impervious to the hustle and bustle of the outside world. They move at their own languorous pace, caught in a tug of war between progress and nostalgia.

| Fenglin Township Fact File Fenglin was once known as Maliwu, an Atayal word meaning "a slope." Located in central Hualien County, it is bounded by the Shoufeng River and Shoufeng Township to the north, the Matai-an River and Kuangfu Township to the south, the Coastal Mountain Range and Fengpin Township to the east, and by Wanjung Township and the Central Mountain Range to the west. The township covers 121 square kilometers and has a population of 12,500. The 70% of its residents who are Hakka make it the most "purely" Hakka of Taiwan's townships. The remaining 30% of the population includes Aborigines, ethnic Chinese, and Taiwan's so-called waishengren-those who emigrated from the Chinese mainland after 1949. Largely agrarian, the township is also home to Lintienshan, once Taiwan's fourth largest tree farm. |

Located in rural Fenglin, Lintienshan was once one of Taiwan's most prosperous tree farms and was even known for a time as "Little Shanghai." The photo shows the railway used to transport lumber.

When Fenglin's tobacco industry was at its peak, there was "a tobacco barn every three steps and smoke billowing every five." Many of these barns still remain (right). The tobacco industry has since moved on. These days, only two Fenglin families are still in the tobacco curing business.

With the rise in interest in herbal healthcare products, Fenglin has become known for its "soymilk asplenium" a variety of bird's nest fern grown with a soymilk dreg fertilizer. The township's 7th marketing group has obtained government certification and each consignment is shipped only after food traceability barcodes are affixed.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)