A Century in the Making: National Palace Museum Treasures Make A Historic Debut in Prague!

August 2025

Taiwan is a country where technology and culture are interwoven on an enduring foundation of cultural heritage threaded with a spirit of innovation. This year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Culture, and the National Palace Museum collaborated on a 2025 Taiwan Culture in Europe project, to bring Taiwan’s distinctive character to audiences across Europe through exhibitions and all sorts of art and cultural events. The program’s slogan: From Tech to Culture, Taiwan Leads the Future! together with its logo melding Roman columns with the precision of microchips, symbolizes the close connections between Taiwan and Europe. Through this series of events, Taiwan affirms its core values of freedom, openness and acceptance of diversity, and further, positions culture as a bridge that connects democracies across the globe.

A Century in the Making: National Palace Museum Treasures Make A Historic Debut in Prague!

From September 11 to December 31, 2025, the National Palace Museum will present its first-ever exhibition in the Czech Republic at the National Museum in Prague—100 Treasures, 100 Stories. More than a landmark event in celebration of the Museum’s centennial, this exhibition is also part of the 2025 Taiwan Culture in Europe project, inviting European audiences to delve into Taiwan’s rich cultural heritage.

On display are 131 masterpieces, unveiled in a single exhibition, including the popular and iconic Jadeite Cabbage and the ingenious Curio Cabinets full of treasures, the magnificent painted scroll Along the River During the Qingming Festival, enigmatic translucent bronze mirrors, and a calligraphy rendering of the famous nostalgic poem Remembering the Past at Red Cliff. The latter two items capture the bustling excitement of ordinary folk at a festival and the refined musings of an ancient scholar, respectively. Visitors will also encounter scenes of legendary gods and demons, the graceful presence of palace cats, auspicious mythical beasts, and carp that leap up waterfalls to transform into dragons, symbolizing overcoming difficulty.

Through these treasures and their stories the exhibition builds cultural resonances between Taiwan and Europe.

National Palace Museum Treasures Journey to Prague!

The Jadeite Cabbage is as iconic to the National Palace Museum as the Mona Lisa is to The Louvre. For generations, countless visitors have made the journey especially to see the delicate carving in person.

It is believed to have been part of Consort Jin’s dowry during the late Qing dynasty, under the Guangxu Emperor.

Carved from a single piece of jade that changes from soft whites to hues of vibrant green, the work exemplifies artisanal skill in using the stone’s natural coloration. Each leaf is rendered with exquisite skill, its veined texture is alive with natural detail, including a katydid and a grasshopper that perch on its leaves. These insects are mentioned in the 11th to 7th century BC Book of Songs as symbolizing sons and grandsons, revealing that the sculpture intertwines classical literature with observation of the natural world. Green and white symbolize purity and integrity, while the insects convey family harmony and prosperity.

The Forbidden City was transformed into a museum in 1925 and the Jadeite Cabbage was displayed there in 1928 at the Yung-ho Palace, since when the piece has undertaken numerous journeys. It traveled with the evacuated artifact collection to Taiwan in 1949 and was stored in a warehouse in Beigou in the central Taiwan town of Wufeng. It went on display in a small exhibition hall there in 1957, and in 1965 was formally exhibited in the newly-constructed National Palace Museum in the Taipei City suburb of Waishuangxi. The Jadeite Cabbage has enchanted generations of visitors with its ingenious use of stone and its familiar subject matter, gaining status as a popular emblem, beloved worldwide as symbolic of Taiwan’s National Palace Museum.

Emperor Qianlong’s “Miniature Curio Cabinet”

Among the treasures of the National Palace Museum is a remarkable category of miniature cabinets filled with tiny objets d’art, offering the grandeur of an eighteenth-century cabinet of curiosities on a miniature scale. These were not just ornamental displays, but rather distilled expressions of imperial taste and worldview.

One of the Museum’s two-tiered cabinet of curiosities is made of red sandalwood, with porcelain panel inlay and marquetry detail. Ingeniously designed, it can be separated into two independent cases. The porcelain panel doors are inscribed with poems composed by the Qianlong Emperor himself. The cabinet enfolds objects from across the known world: Chinese paintings, bronzes, and jades alongside Japanese lacquer boxes and European pocket watches, revealing a breadth of collection that embraced both East and West.

What makes this cabinet especially significant is its inclusion of pieces made by the emperor’s closest ministers. Miniature paintings and calligraphy by eminent scholar-officials of the Qianlong reign, including the first-rank scholar Yu Minzhong, accomplished painter Qian Weicheng, and the third-rank scholar Wang Jihua, were created expressly for these curio cabinets. The collection was installed in the Yangxin Hall, and became a shared interest between ruler and ministers, and a luminous emblem of the dynasty’s glory.

The cabinets were more than repositories of precious objects. Each is a microcosm of the eighteenth-century Qing court: a single, compact chest that contains within it the currents of Sino-Western exchange, the bonds of sovereign and servant, and the refined sensibilities of an emperor who sought to embody civilization itself.

When Touched by Sunlight, the Ancient Mirror Reveals Its Artistry

Before the advent of glass mirrors, the ancients relied on polished bronze surfaces—one side gleaming enough to reflect a face, the other adorned with intricate motifs and auspicious inscriptions, at once practical and regal.

In the late Western Han, a near-magical creation emerged: the translucent mirror. When placed in direct sunlight, these mirrors cast patterns and inscriptions from their decorated reverse onto a white wall, as though the bronze itself was transparent. This marvel captivated the literati across the centuries. The Tang tale Record of the Ancient Mirror describes this wonder; in later dynasties, figures such as the Jin poet Ma Jiuchou and the Yuan calligrapher Xianyu Shu praised them in verse and prose, treasuring such rare objects and fueling waves of collecting fervor.

The Qianlong Emperor, a devoted connoisseur of antiquities, recorded five such mirrors in his Catalogue of Ancient Bronzes. Among them is the National Palace Museum’s prized Western Han bronze mirror. On its reverse, seven raised bosses are encircled by images of birds, beasts, and winged figures, alongside a nineteen-character inscription: “Exert yourself in governance, with daily and monthly progress. With lifelong diligence comes fortune through reverence, a blessing for descendants.” Both moral exhortation and a prayer for prosperity, the text embodies the mirror’s dual nature of reflection and revelation.

The translucent mirror is a testament to the extraordinary metallurgical skill of the Western Han dynasty and embodies mystery, being cherished and praised by generations of poets, scholars, and collectors. Through its mysterious play of light, it carries a story of skilled artistry and wonder across the span of two millennia.

Red Cliffs: From Battlefield to Eternal Moonlit River in Literati Imagination

During the Three Kingdoms period (220–265 CE), the warlord Cao Cao led his forces south in the thirteenth year of Jian’an (208 CE), only to be defeated by Zhou Yu at the Red Cliffs—an event that cemented the tripartite division of China. The precise location of the battlefield remains contested and at least five sites lay claim to the name, although most traditions associate it with the riverbanks southwest of Jiayu County in Hubei.

Centuries later, the Northern Song literary giant Su Shi (Su Dongpo, 1037–1101), was exiled to Huangzhou after the government censorship versus artistic freedom prosecution against him known as the “Crow Terrace Poetry Case.” In exile he pondered on the Red Cliffs near the town and embraced them as an ancient battlefield. Twice, in 1082, he took a boat ride to contemplate the landmark, and was inspired to write two immortal masterpieces, The Former Ode on the Red Cliff and The Latter Ode on the Red Cliff. Through the characters of Cao and Zhou, Su transformed the battle into meditations on human transience, grandeur, and loss. With the popularity of Su’s odes and the Ming novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which includes the “Burning of Red Cliffs,” the site became a cultural landmark, inspiring artistic and literary creation.

From the Ming dynasty onward, artists typically depicted Red Cliff scenes with towering riverbanks and small skiffs adrift beneath the moon. This exhibition includes fine examples in carved lacquer and chicken-blood stone, delicately rendering the poet Su’s boat upon surging waves, framed by craggy cliffs and clustered trees. A scroll version uniting word and image dates from 1556, with calligraphy by Wen Zhengming of Su’s Red Cliff ode, and the painter Gu Datian’s 1592 illustration of the Red Cliff mounted together on a single scroll by a discerning collector. The scroll depicts a serene autumn riverside—Su Shi and his companions preparing to embark, a fisherman presenting his catch, and an attendant standing quietly nearby—imbued with the refined charm of literati leisure.

Red Cliffs, then, is not merely the site of a battle. It is a river landscape that, through poetry, prose, painting, and craft, has offered inspiration across a thousand years, transforming conflict into an eternal stage for moonlit reflection.

Qing Dynasty, 18th Century ― Redlacquer screen depicting the poet Su Dongpo’s boat journey to the Red Cliffs

Shi Tianzhang, Chicken-blood stone seal carved with the Red Cliffs carving

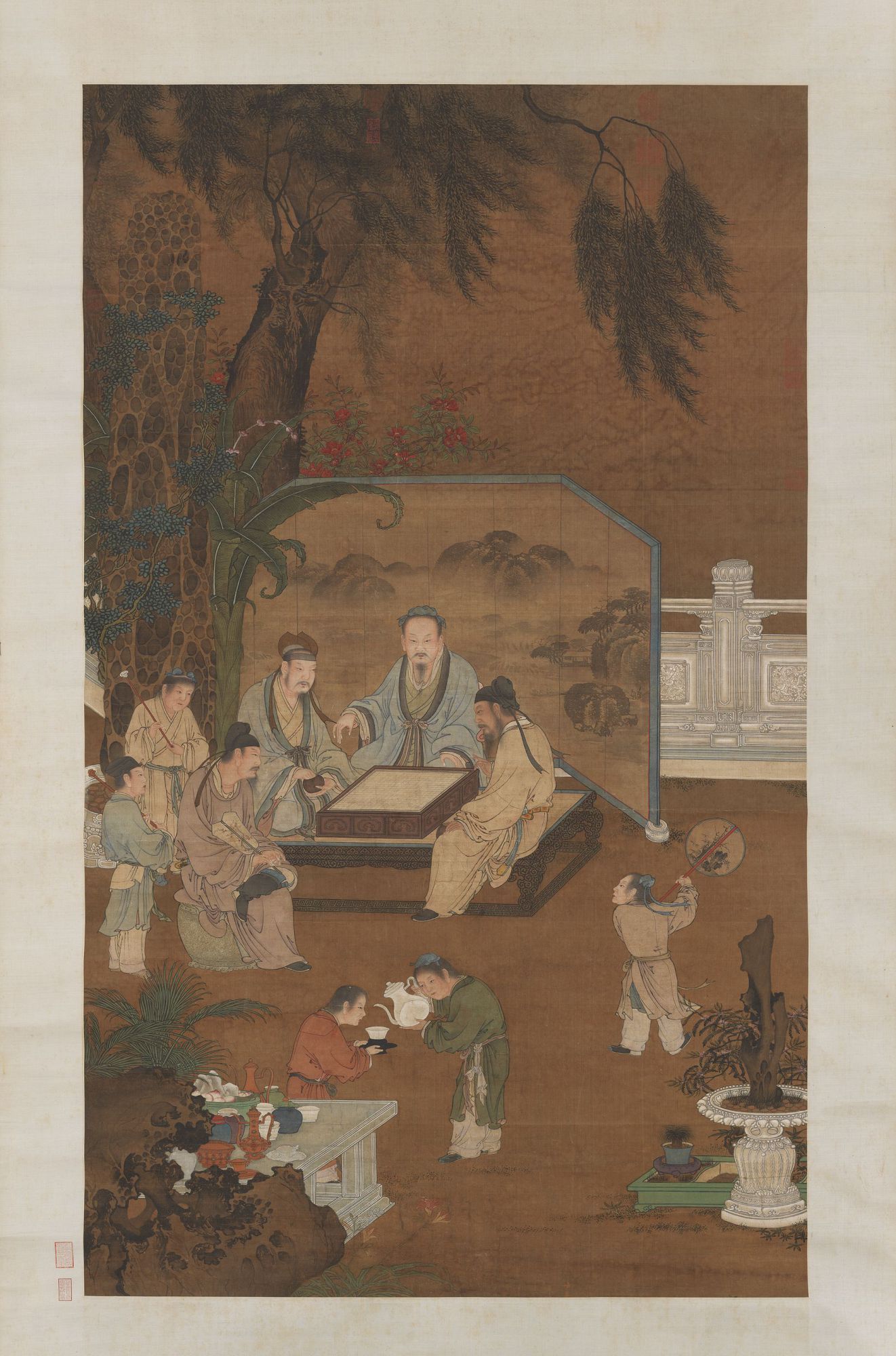

The Daily Life of the Ancient Literati: A World of Poetry and Objects

The life of the ancient Chinese literati was steeped in refinement and reflected the intellectual spirit of the age. Music, chess, calligraphy and painting formed the pillars of a cultivated world; the scent of incense, the savor of tea, reading poetry and prose, and writing verse were cherished daily pursuits.

No poetic gathering or refined assembly was complete without the presence of fine scholarly implements—water pots, inkstones, brush rests, water droppers, and brush holders. Some were contemporary masterpieces, others antiques handed down through generations. To the literati, appreciation of such objects was a dialogue across time: studying material and texture, contemplating patterns and ornament, they discerned profound layers of history and culture.

Antiques held a singular allure for scholar officials. The objets d’art carried stories, lineages, and echoes of vanished lives. To trace their origins, techniques, and historical settings was to endow them with life, transforming each into a subject of fascination and conversation. Collecting such objects was an indulgence in beauty and an assertion of taste; an aesthetic discernment that was a visible emblem of social standing.

Every antiquity became a letter left by time to the literati—a vessel brimming with memory, meaning, and continuity, linking the present with the past.

The Eighteen Scholars― Hanging Scroll, Song Dynasty

The Eighteen Scholars― Hanging Scroll, Song Dynasty

The Eighteen Scholars― Hanging Scroll, Song Dynasty

The Eighteen Scholars― Hanging Scroll, Song Dynasty

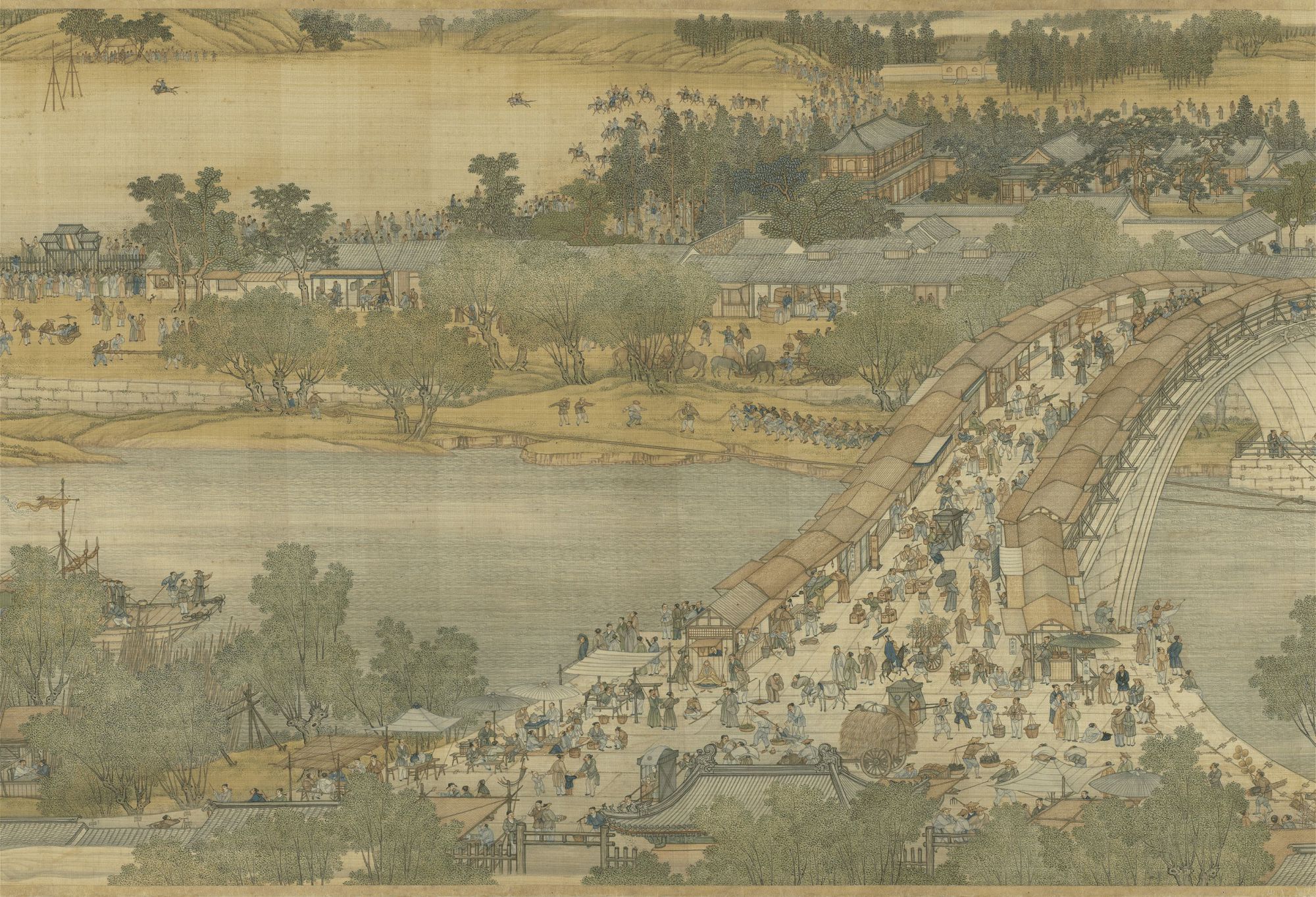

Splendors of a Flourishing Era: Along the River During the Qingming Festival

In the long tradition of Chinese art, depictions of seasonal festivals and visions of peace and prosperity have always held a special place, celebrated for rendering the vitality of daily life and the grandeur of the era. With meticulous brushwork and sweeping scope, such works capture both the pulse of the people and the splendor of the city.

The Qing dynasty version of Along the River During the Qingming Festival is among the most renowned of the genre. The scroll unfolds along the banks of the river in the Northern Song capital, where an arched bridge spans the waterway. Boats, mule carts, and ox-drawn wagons carry goods along the bustling river and through the streets lined with shops and crowded with vendors. The throng of figures, each engaged in their work and pursuits, conveys an atmosphere of both industry and exuberant life.

This work synthesizes elements of earlier versions and adds details of the Imperial city in the Qing dynasty. In addition to shops adorned with signboards, it shows Western-style buildings and culminates in a resplendent palace at the scroll’s end, in striking contrast to the vibrant but humble street scenes. The variety of life it portrays is extraordinary: a wedding procession, theatrical performances, acrobats, trade, and human interaction. Within a single continuous composition, there are city walls, verdant hills, and a multitude of human figures, constructing an idealized vision of the empire’s capital at its zenith.

It is more than a painting; it is a look back across a millennium to a vivid panorama of a flourishing age caught in brush and ink.

Ghosts and the Human Realm: A Millennium of Imagination

Humanity has always pondered the great enigma: when the body perishes, where does the soul go? Might there exist, beyond the dimensions perceptible to us, another realm—unseen yet real?

In the Shuowen Jiezi (ca. 58–147 CE), the Eastern Han scholar Xu Shen defined the word ghost as “what humans become after death,” describing its form as a human body with a spirit’s head—a reflection of ancient fears and imaginings of the unknown. Such spirits became a fertile source of inspiration for writers and painters, while also giving rise to the legendary lord of exorcism, Zhong Kui.

Celebrated for his upright virtues and strength, Zhong Kui was believed to banish demons and exorcise evil. On view here is Zhong Kui on the Fifth Day of the Fifth Month, (The Dragon Boat Festival) painted in 1563 by Qian Gu of the Wu School, in which the figure looms with fiery vigor and indomitable force. Over time, popular belief intertwined Zhong Kui with the rituals of the Dragon Boat Festival and his image appeared on blue-and-white porcelain and red overlay white glass snuff bottles, extending his role as guardian and talisman.

The writer Pu Songling (1640–1715) assembled 491 tales of encounters between humans and spirits, immortals, and demons in his Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (Liaozhai zhiyi), extending the scope of supernatural imagination and offering fresh ways to confront the mysteries of existence.

In both Eastern and Western legends and art, the ghost stands at the intersection of culture, belief, and creativity—a mirror of humanity’s enduring attempt to give form to the unseen.

Qing Dynasty, 19th Century ―Blue and white porcelain snuff bottle decorated with Zhong Kui, Lord of Exorcism

Qing Dynasty ―Red on snow white glass snuff bottle with a Zhong Kui, Lord of Exorcism motif

Graceful Figures Across East and West — The Cat

In Czech culture and daily life, the cat has long held a cherished place. Their supple forms are a familiar sight on the streets of Prague, while the Czech writer Franz Kafka wrote reflections on these elegant, enigmatic creatures in his work. With their endearing appearance, grace and agility, cats have, since antiquity, been regarded as emblems of refinement and prosperity.

In Chinese art, too, cats have inspired poets and painters alike. The Song painter Li Di and the Qing artist Shen Zhenlin captured the playful vitality of their movements and the softness of their fur with delicate brushwork. Jade carvers fixed their essence in poses crafted with gentle humor, in miniature sculptures. In the exhibition are two such jade cats—small enough to rest in the palm of a hand, their lifelike presence enhanced by use of the stone’s hue and grain.

In Chinese culture, the word for “cat” (mao) resonates with the word meaning “long life in old age,” so that art depicting cats was also a token of blessing and well-being.

In both the East and West, the cat is a daily companion and a perennial figure in art: graceful and enduring.

An Auspicious Beast from Afar — The Lion

Although lions are not native to China, records of “tribute lions from the Western Regions” appear as early as the Han dynasty, reflecting exchanges with Central Asia and India. The Book of the Later Han (Hou Hanshu) explicitly mentions these exotic creatures. Two distinct names for lions entered the Chinese lexicon through different routes: suan-ni (狻猊), from India, and shizi (獅子), a later phonetic rendering that arrived via Iran during the medieval period.

As rare and awe-inspiring beasts, lions in ancient Chinese society came to embody majesty, authority, and the promise of peace. With the spread of Buddhism, the lion assumed an even greater role as a sacred guardian and auspicious beast, frequently represented in Buddhist art as a symbol of Dharma power.

In the National Palace Museum collection is a Ming dynasty carved red lacquer box depicting “two lions playing with a ball,” a lively motif signifying good fortune. From the eighteenth century comes a pair of cloisonné enamel lions: the male with his paw upon a ball, the female with her cub, their vigorous forms evoking blessings of prosperity and continuity. In Qing court painting, monumental images of lions changed the compositional traditions of earlier Ming prototypes, by placing them in landscapes of trees and rivers, perhaps reflecting imagined visions of their distant homelands.

Although lions originated far beyond China’s borders, their images reshaped the visual language of Chinese art and represented both auspicious events and power.

Lion― Qing Dynasty

Qing Dynasty ―Pair of cloisonné enamel lions

Qing Dynasty ―Pair of cloisonné enamel lions

The Carp: An Auspicious Symbol In Both East and West

In many Asian cultures, the carp is a delicacy for the table and embodies joy, filial devotion, perseverance and the hope of success.

In the Czech Republic, roast carp is served on Christmas Eve as a symbol of peace and happiness. In Sinitic culture, the festive dish of sweet-and-sour carp (tangcu liyu) conveys the blessing of “abundance year after year.” In the ancient tale of the Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars, devoted son Wang Xiang lay down on a frozen lake to catch a carp to nourish his stepmother—a story that elevated the fish as a symbol of filial piety and made it a poignant subject in Chinese painting.

There is also a famous legend of carp leaping over the Dragon Gate, a large waterfall on the Yellow River. Each spring, carp swim upstream to spawn, and those that successfully leap up the mighty Dragon Gate are said to transform into dragons. For centuries, this metamorphosis served as a metaphor for academic ambition and a collective yearning for transcendence, upward mobility, and enduring success.

From the Christmas tables of central Europe to the folklore of China, the carp has come to embody a dual inheritance—both a bearer of blessings and a timeless emblem of the indomitable spirit of striving.