More than Just Tofu:

Soy’s Many Splendors

Esther Tseng / photos Jimmy Lin / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

June 2025

00:00

As well as being an excellent source of protein, tofu is low in carbohydrates and calories and is regarded as something of a superfood for those looking to lose weight.

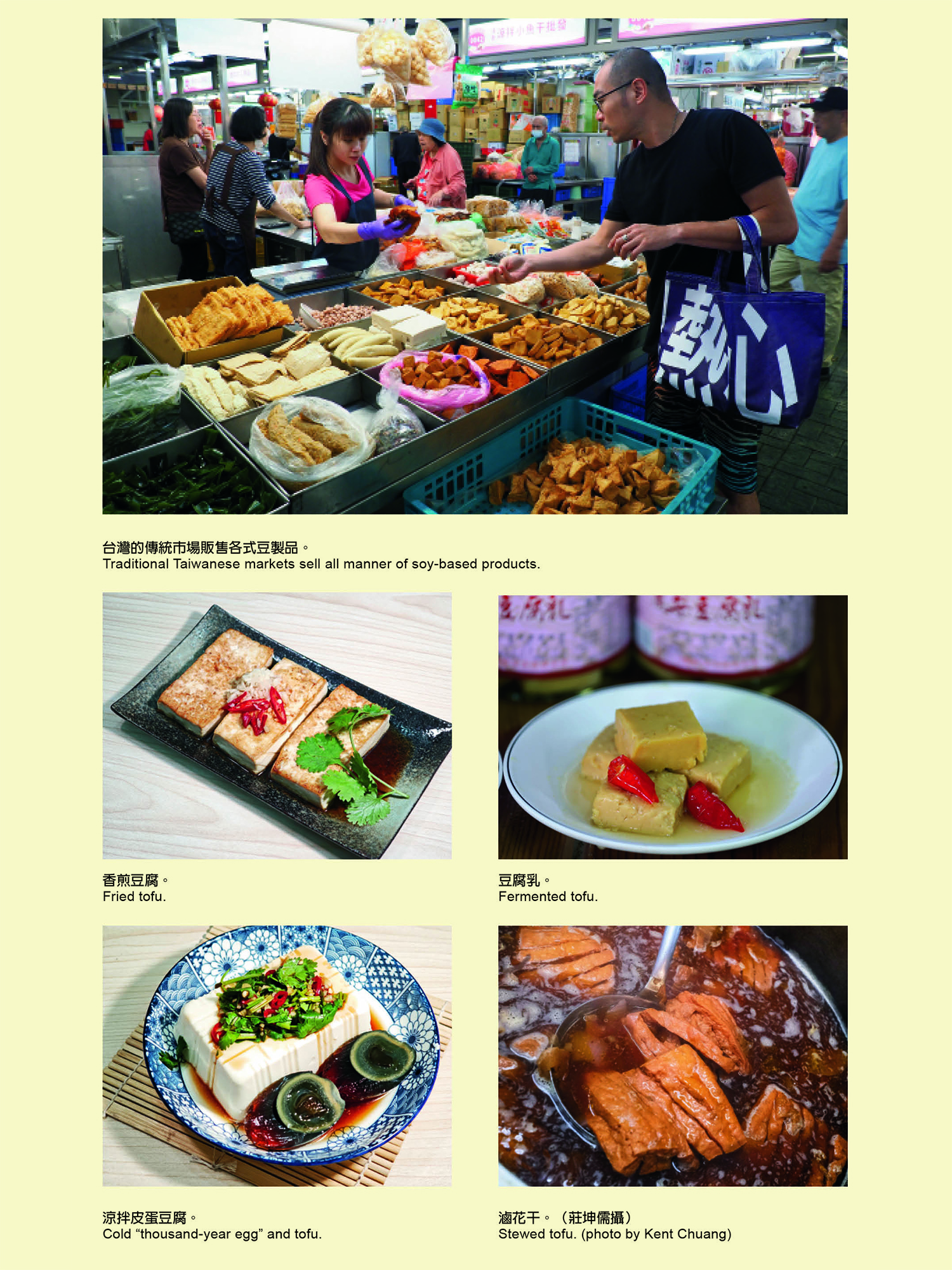

Savory congee and rice noodle soup pair perfectly with crispy fried tofu; braised pork over rice or chicken over rice go best with a side of century egg tofu or braised tofu; and when having braised snacks or Taiwanese popcorn chicken, nothing hits the spot quite like dried tofu or tofu skin. Taiwan’s diverse range of soy products offers seemingly endless options—the makings of both grand feasts and small snacks that leave lasting impressions.

Some producers of tofu in Taiwan are so large that they are listed on the stock market. There are festivals and old quarters of towns famous for their tofu, whether fresh or dried, and there are all manner of tofu shops and retail chains, as well as tofu-related spots famous for social media photos. Have you experienced the wide variety of soy products that Taiwan has to offer?

Soy products are immensely popular in Taiwan today, but professor Kao Tsai-hua from the Department of Food Science at Fu Jen Catholic University notes that there are records of soy milk and tofu consumption dating all the way back to the Han Dynasty. A symbol of Eastern culture, these foods have a history of over 2,000 years.

Asians and Westerners make different uses of soybeans. Chris Lin, general manager of the soy product firm Soyaway, explains that in Western countries such as the United States soybeans are primarily grown for extracting soybean oil and producing soybean protein for animal feed. Asians, on the other hand, directly use soybeans to make a variety of products, including tofu and dried tofu.

Kao notes that Asians are so accustomed to the taste of soybeans that they even refer to them as “field meat” in a nod to their nutritional value, which is indeed comparable to meat.

Soy products are everyday staples easily found in traditional markets and supermarkets across Taiwan. Iconic local delicacies like Daxi dried tofu and Shenkeng tofu are at once delectable fruits of culinary craftsmanship and rich representations of a cultural heritage, says Kao. Concerned about fitness, the younger generation is increasingly embracing burgers made with plant-based meat, soy ice creams, plant milks, and soy protein powders—harmoniously blending the traditional with the modern.

To offer readers an in-depth look at the evolution of soy products in Taiwan, we visited some of Taiwan’s leading producers of tofu skin and organic tofu.

First up is Jiu Dai Foods, which has processing plants in Yunlin County at Citong and Lunbei.

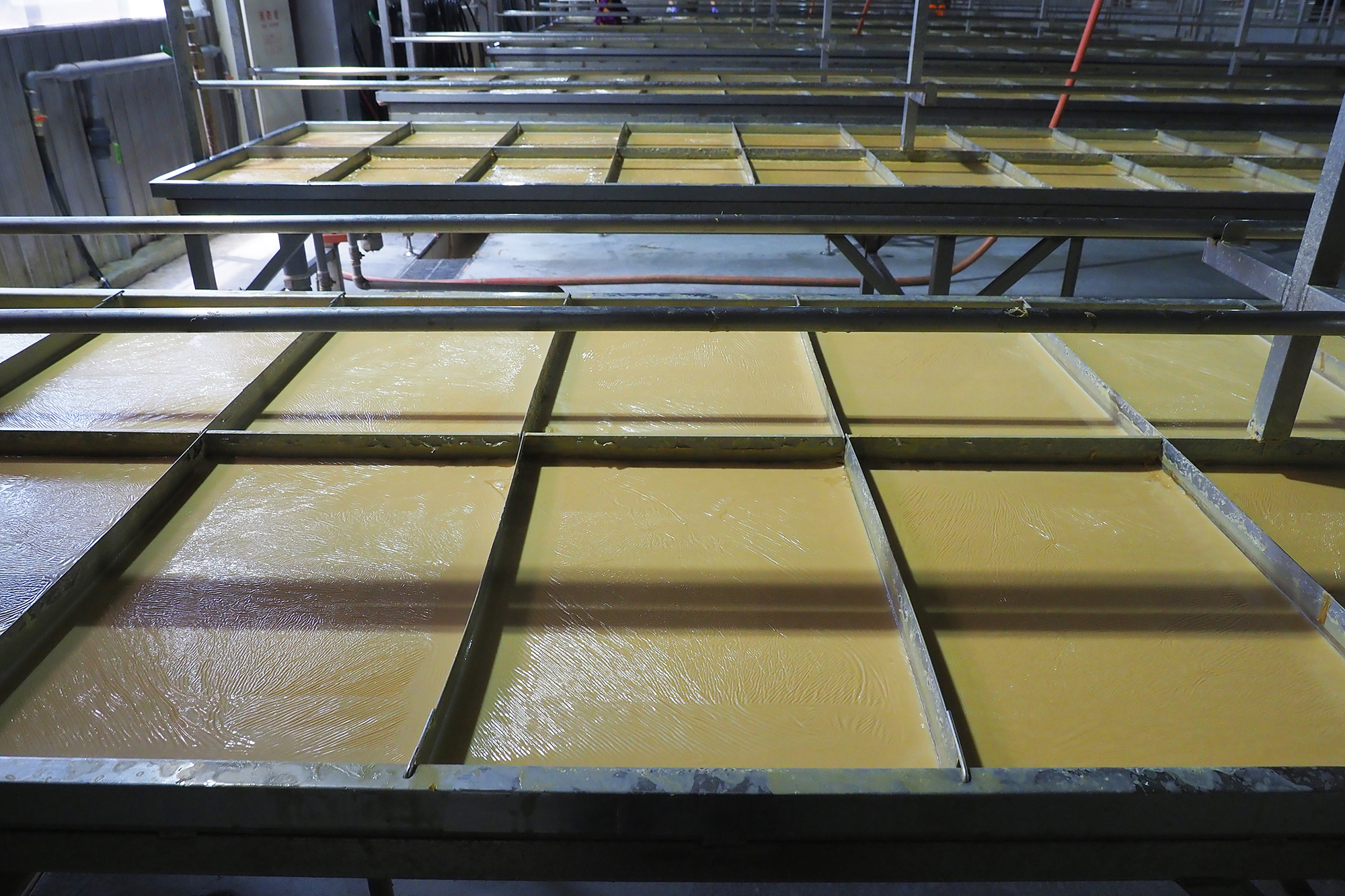

Wearing shoe covers and head coverings, we step into the heat and steamy mist of a fully enclosed tofu skin factory. Pipes carrying water vapor at 70‡80°C heat the factory’s cooking pans, causing the surface of the soy milk to congeal into thin films. Workers clad in air-cooled jackets skillfully lift these paper-thin tofu skins with bamboo chopsticks every ten minutes. Folded into neat squares, they become “tofu skin parcels.”

Tofu skins vs. tofu skin parcels

What’s the difference between tofu skins and tofu skin parcels? Lee Dong-jing, general manager of Jiu Dai Foods, explains that a tofu skin parcel is simply a folded square of several layers of tofu skin. The parcels can be used fresh, with a smooth and tender texture, or deep-fried at low temperatures.

Once dried, tofu skin can be rolled up and deep-fried to become fried tofu skin, whether of the small or large variety. The small type is thick and hearty, whereas the large type is thin and crispy, but both are suitable for stir-frying, braising, stewing, or boiling. When tofu skin is cut into pieces and deep-fried, it turns into small, twisted segments known as jiaoluo (“conch rolls”), prized for their chewy texture and commonly used in hotpot dishes.

After the workers lift the tofu skin, they can roll it using three long chopsticks to form fuzhu (dried beancurd sticks). When tofu skin is baked and pressed, it becomes qianzhang—thin tofu sheets used as wrappers for other ingredients. If the tofu skin is rolled up and deep-fried, it becomes a tofu skin roll, which is a popular ingredient in hotpots and braised dishes.

In the area from Changhua to Tainan, there is a unique type of soy product called douji (tāu-ki in Taiwanese), which can be cooked with braised meat or stir-fried vegetables. Wang Yizheng, owner of the food wholesaler Dachenghao, says that unlike douzao or red douzhi (sweetened deep-fried tofu products that are commonly eaten with rice porridge or found in bento boxes), douji is made by spraying out soybean flour dough from a machine and then deep-frying it. But the food has fallen from favor and is gradually disappearing, with the number of factories producing it in steep decline.

Homeland of tofu skin

Yunlin County, where Jiu Dai Foods is located, has 43 tofu skin factories, accounting for nearly 70% of the 64 such factories in all of Taiwan. In particular, Citong Township in Yunlin is known as “the homeland of tofu skin.”

Although large-scale tofu skin production has only emerged in Taiwan in the past few decades, in Citong it is concentrated among families with one of three surnames—Chen, Lin, or Liao—all of whom are distant relatives within the same ancestral clan.

Despite having the word for “bean” in their name, doulun are in fact made with wheat flour..

Douji tofu chips.

Pressed tofu skin.

Expanding business through barcodes

Lee Dong-jing returned to help with his wife’s family business after earning a PhD in electrical engineering from National Cheng Kung University and working at the Industrial Technology Research Institute. After his first winter at the family firm, he was taken aback when his father-in-law asked him to lay off four employees.

“Everyone had worked hard through the winter, but come summer, four people were going to lose their jobs. That’s when I realized that this is just the way things are at tofu skin factories: Because fewer people eat hotpot in the summer, the demand for tofu skin decreases, which leads to layoffs.” Wishing there was a way to avoid this misfortune, Lee learned on a business trip that one food producer’s tofu skin orders didn’t actually decrease in the summer. It turned out that they were selling tofu skin to New Zealand and Australia in the Southern Hemisphere.

Living up to his PhD credentials, Lee found an international barcode on the packaging of a tofu skin product sold in Australia. He tracked down the distributor and started supplying directly to ethnic Chinese supermarkets in Australia. Then, another distributor found Jiu Dai Foods through its barcode, prompting Lee to expand into the United States and Canada, where Chinese communities and followers of the Yiguandao religion are the main consumers of Jiu Dai’s products.

Tofu skin starts as a thin film that forms on the surface of soy milk after heating.

Smoked tofu skin rolls with vegetable filling.

A worker skillfully lifts off a tofu skin with bamboo chopsticks.

Emphasis on food safety

Lee has vertically integrated the entire process of making tofu skin, from obtaining raw materials to packaging. He also obtained ISO 22000 and HACCP food safety certifications, which have attracted major clients that prioritize food safety, including the Taiwan Railway Corporation and 7-Eleven, as well as restaurants such as Smartfish and those belonging to the Wowprime group.

At the helm for eight years, Lee has expanded his father-in-law’s firm from a small factory with only seven or eight employees into a major tofu skin manufacturer with four factories and about 160 employees. In recent years, the popularity of snail rice noodles and sauerkraut fish in Taiwan, as well as the trend of eating hotpot in summer (thanks to strong air conditioning), have boosted sales of tofu skin and dried tofu sticks, which continue to be important hotpot ingredients.

Tofu skin makes an excellent ingredient for hotpot.

The dried tofu stick workshop at Jiu Dai Foods’ tofu skin factory.

The extracted tofu skins must be dried before they are deep-fried.

Organic agriculture

Lin Guozhen, the general manager of Soyaway, points to environmental considerations in favor of soy products: “Soy milk has a significantly smaller carbon footprint and environmental impact than animal milk. Moreover, soybean cultivation not only doesn’t harm the environment, but the plant’s root system actually fixes nitrogen into the soil. It prompted our ancestors to develop the wisdom of crop rotation, planting soybeans after every two rice crops.”

Soyaway was founded on the principle of supporting organic agriculture. More than two decades ago, its founder Huang Xuewei discovered that Japanese farmers were growing organic soybeans to supply customers who used them in the production of organic processed foods. That inspired him to start his own business and make tofu.

After learning how to make tofu from a master in Beipu, Hsinchu County, and enduring seven tough, unprofitable years, Soyaway gained support from Leezen, the organic distribution network established by the late Buddhist priest Master Jih-Chang. Fashioning its own unique business model, it has become one of Taiwan’s top three organic soybean product manufacturers.

A long pressing process results in a firmer tofu or even eventually dried tofu.

Braised dried tofu makes a great everyday side dish.

When packaged, tofu is immersed in filtered water to prevent it from drying out.

Eco-friendly food chain

In the Soyaway factory, workers start at 6 a.m. Having soaked the soybeans overnight, they grind and cook them to make soy milk before adding coagulants to curdle the milk, turning it into tofu curds.

Next, the curds are broken up before being manually scooped into tofu molds. After one layer is drained of excess liquid, another layer is added, and the molds are moved to a press for shaping. If pressed for a short time, the tofu retains more moisture and becomes silky soft tofu (nen doufu)—smooth and tender like cream. A longer pressing time results in firm tofu (ban doufu) or dried tofu (dougan, a.k.a. pressed tofu), known for its chewy texture. Deep-frying the tofu produces fried tofu (you doufu). Simmering dried tofu in a soy-sauce marinade makes braised tofu (lu dougan), with its dense mouthfeel. Cutting tofu into blocks and freezing it turns it into frozen tofu (dong doufu), which has a spongy texture ideal for absorbing flavors.

It is truly remarkable, says Lin, that one basic foodstuff can be transformed into such a wide variety of foods.

From Tomb Sweeping Day in early spring to the Dragon Boat Festival in late spring is the peak season for making doufuru (fermented tofu). Salty, fragrant and appetizing, fermented tofu is a great side dish to go with rice porridge.

Whether because of lactose intolerance or ethical concerns about the treatment of animals, many Asians don’t consume animal milk. Soy milk makes an excellent substitute.

To make tofu tempura, first grind up tofu or dried tofu before shaping and deep-frying it.

Lin Guozhen, general manager of Soyaway, believes that organic soybeans not only create more healthy and nutritious food for consumers, but they also help to protect the health of farmers and the soil.

A legacy of beautiful flavor

Lin says that the goal is to restore the natural aroma of the soybeans and showcase their authentic flavor, catering to consumers who prioritize health and reducing calorie consumption. Without needing three-cup sauce, braising, or spicy seasoning, if you simply steam a block of tofu slightly in a rice cooker and then cut it open, the natural soybean aroma will emerge. Just dipping it in a thick soy sauce makes it delicious.

To preserve the original nutritional value and flavor of the soybeans, Soyaway grinds them with slow-turning traditional millstones weighing 300 kilograms, but powered by electric motors instead of the traditional donkey. Grinding the beans, black sesame, and black glutinous rice in this way doesn’t destroy their nutrients as would happen with blades moving at high speeds. What’s more, they don’t filter out the pulp, so all the ingredients remain in a drink they call “three black treasures.” “We use the methods of our ancestors to make soy milk,” explains Lin. “It’s an innovation but also retro.”

Rich in nutritional value, Taiwan’s soy products have become increasingly numerous and diverse in step with advancements in food technology and the growing number of vegetarians and others who prioritize environmental sustainability and healthy living. “Invented two millennia ago,” wrote Hao Guangcai in a poem, “tofu has nourished multitudes, bringing warmth to countless dishes and joy with every block.” Soy products have truly enhanced the quality of our dietary lives.

Soyaway’s original shop is located in a historic building in the old quarter of Hukou, Hsinchu County.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)