From Teaching Overseas Chinese to Teaching Chinese Overseas—An Interview with OCAC Minister Steven Chen

interview by Kobe Chen / photos Chuang Kung-ju / tr. by Jonathan Barnard

August 2014

Taiwan’s efforts to teach the Chinese language overseas have been closely tied up with the education of overseas ethnic Chinese. For over 60 years, that work has boosted the spirits of overseas Chinese and advanced the mission of promoting Chinese culture. Even today, when Taiwan is competing intensely with mainland China in the educational realm, the education of overseas Chinese remains an important pillar of the ROC’s campaign to teach Chinese overseas.

In this issue Taiwan Panorama has an exclusive interview with Overseas Community Affairs Council minister Steven Chen, who sheds light on the situation that Taiwan faces with regard to teaching Chinese abroad.

Q: In the market for Chinese language classes, how does Taiwan contend against the strength of mainland China?

A: Mainland China has vast sums of money to spend, but Taiwan can establish a strong position thanks to three factors: our foothold in overseas Chinese communities, our use of traditional characters and our educational innovativeness.

Because the mainland does not recognize dual citizenship and used to be relatively sealed off from the rest of the world, its hold on overseas Chinese communities has traditionally been weak. What’s more, Taiwan’s efforts at building relationships with overseas communities are quite mature. Overseas schools and overseas citizen organizations are well developed, and they provide an excellent channel for promoting Chinese classes.

In recent years mainland China has launched its own efforts of outreach to overseas Chinese communities, modelled largely on Taiwan’s. But some aspects can’t be copied. The best example is the use of traditional characters.

Steven Chen of the Overseas Community Affairs Council believes that Taiwan’s experience with education in overseas Chinese communities gives it a big advantage when promoting Chinese language classes abroad.

Traditional characters have structural and logical integrity. After learning traditional characters, it’s easy to pick up simplified characters. It’s much harder in reverse. More importantly, when learning a language, it’s essential to grasp the cultural pulse behind it. The Cultural Revolution was devastating for traditional culture on the mainland. They may want to revive it now, but that’s no easy matter. Taiwan uses traditional characters and has enjoyed an unbroken legacy of traditional Chinese culture, so it’s well suited to meeting the cultural curiosity of foreigners. For instance, traditional calligraphy, inscriptions and poetry are all written in traditional characters. If you have only studied simplified characters, you may not even be able to read the plaques and tablets at Chinese scenic sites.

Currently, Chinese departments in research universities around the world must teach traditional characters, or their students will not be able to conduct research. Most universities in the US still teach traditional characters. We can promote an approach of “recognizing traditional characters and writing simplified ones,” to make it easier when writing but to avoid limiting understanding. That’s something mainland China can’t do.

Q: What threat does the rapid growth of Confucius Institutes pose to Taiwan’s educational efforts overseas?

A: Confucius Institutes have indeed been expanding quickly, but our efforts have all along been focused on education in ethnic Chinese communities, which hasn’t been adversely affected. The key is cultural identification.

At its core, education of overseas Chinese is about the transmission of cultural inheritance, and overseas Chinese who learned traditional characters naturally want their children to do the same. Consequently, this market is quite stable. The difference is that we haven’t grasped firmly the new market opportunities that have arisen in recent years due to the growing popularity of studying the language among those who are not ethnic Chinese.

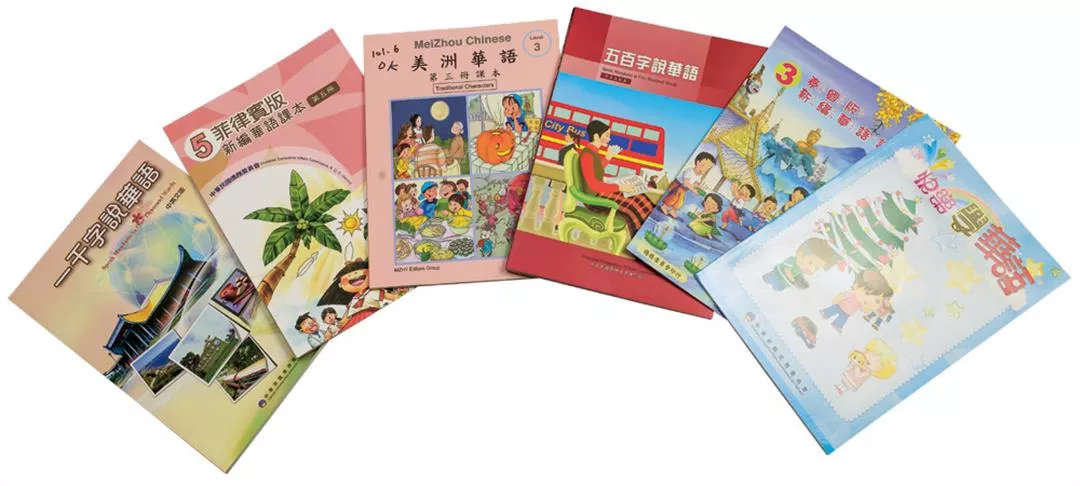

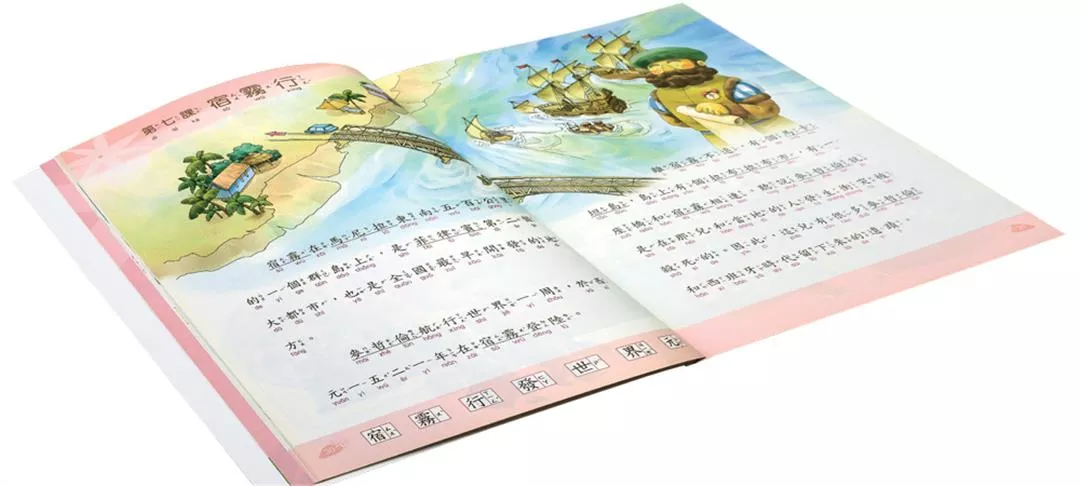

The OCAC provides textbooks and other teaching materials that are tailored to the needs of the locale. The various editions differ markedly.

Confucius Institutes are inherently controversial. In particular, at universities that put stock in academic freedom, there has been a lot of opposition to these institutes’ tight control over faculty, teaching materials and pedagogy. In class, discussions about Taiwan, Tibet, Tian’anmen and Falun Gong are not permitted, and those restrictions have caused a lot of dissatisfaction. Some schools are even willing to spend their own money on Taiwanese educational materials, rather than use the materials provided by the mainland for free. That clearly demonstrates that mainland China still faces some limitations in its promotion of education. All of this gives us opportunities.

Q: Teaching materials can affect values. They are an important part of education. How can Taiwan go about promoting the use of teaching materials employing traditional characters?

A: Apart from the teaching materials developed and compiled by overseas Chinese-language schools or the teachers themselves, the Overseas Community Affairs Council also actively provides materials to overseas Chinese schools. Via their widespread use, we are able to build “brand image.”

What’s more, to promote the learning of both simplified and traditional characters in regular local schools abroad, as well as in schools serving overseas Chinese communities, we have adopted an approach of “placing traditional and simplified characters side by side.” We use materials aimed at teaching traditional characters that include the simplified characters next to them, for the sake of comparison. What’s more, these texts also include Hanyu Pinyin Romanization, to make it easy for students to learn.

The OCAC’s E-Learning Huayu of Taiwan website [at HuayuWorld.org] has been gathering teaching materials of all kinds for more than a decade, creating a vast database. Currently, it is the world’s most comprehensive website of Chinese-language educational materials. All of its resources can be downloaded, including curriculum guides, workbooks, and lesson plans. The site is a good friend to Chinese-language teachers overseas.

The OCAC provides textbooks and other teaching materials that are tailored to the needs of the locale. The various editions differ markedly.

Q: Digital technology is Taiwan’s strong suit. What digital resources are being used in Chinese instruction?

A: In 2010 we constructed a synchronous e-learning platform on the HuayuWorld.org website that provides a global space for instant educational support and sharing of educational experiences. In 2013, in response to the trend toward cloud-based learning, we added a “cloud school,” a “resource exchange platform,” an “ebook store,” and other successful cloud-based learning applications.

The website has used virtual channels to expand the reach of Taiwan’s Chinese education. Currently, it has some 30,000 members, but most are teachers. The goal is to attract more students, as well as to provide abundant reconfigurable digital teaching materials that allow teachers to make best creative use of them.

Because the level of digitalization varies from place to place, in order to reduce the digital divide OCAC, focusing on overseas Chinese schools and cultural organizations with strong potential, is providing assistance in establishing digital learning centers to serve a variety of functions including language instruction, consultation services, teacher training, cultural exchange and display of teaching resources. These have become a marketing and promotional stronghold for Taiwan’s overseas Chinese education efforts. From 2007 to 2014, 64 digital learning centers have been established.

Q: The Ministry of Education is currently researching an eight-year plan for exporting Chinese culture that aims to integrate Taiwan’s Chinese education resources. How can OCAC, as a cornerstone of overseas Chinese education, best support this plan?

A: The eight-year plan has established an administrative unit specifically responsible for Chinese language education and a program for integrating resources. Apart from supporting digital learning centers, the OCAC also provides advice and support to more than 90 organizations and more than 2000 schools. Those channels are already up and running. Those faculty are already teaching.

Currently, we are pursuing a strategy of “one overseas Chinese school paired with one mainstream school,” aiming to connect Chinese Schools in the overseas Chinese community with mainstream schools in the same areas, so they can work together to promote Chinese-language education and the learning of traditional characters through Chinese language and culture festivals, educational trips to Taiwan and other means. Because of rising demand for Chinese education, many mainstream schools are making inquiries themselves about this program. There are more than 100 applications a year in the United States. Demand is high.

Exporting educational talentThe eight-year plan also includes a program for teacher training. The OCAC has long been a bastion of Chinese-language education. In recent years, apart from encouraging Taiwan’s universities to select students to send overseas for internships at Chinese language schools, the OCAC has launched a program for youths to volunteer for service at schools abroad. In 2013, for instance, a total of 41 volunteer groups with a total of 292 volunteers set off for 39 schools in Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. They worked in libraries and as computer, Chinese, English and math instructors.

Young men performing alternative (non-military) national service are also an important source of personnel. Since 2007 we have dispatched 209 of them to overseas Chinese communities in the Philippines, Korea, Japan and Panama. Apart from teaching Chinese, they have also taught math, information science, biology and other courses.

Many of these young men end up accepting appointments at those overseas schools. For Japan in particular, it seems that almost all of those who go stay on. It bears witness to the high demand for Chinese instructors abroad.

Working with NGOsQ: It’s not just government departments that need to coordinate their efforts; cooperation between government and citizen groups is also important. What citizen groups is OCAC currently working with?

A: Citizen groups are actively engaging in activities that promote the learning of Chinese. Take the Buddha’s Light International Association: Wherever it sets up branch offices, it offers Chinese classes. It has even established universities in the United States and Australia. The association plays an important role in spreading Chinese education.

What’s more, the Mandarin Daily News has a well-established brand. Many overseas Chinese send their children to Taiwan to take classes at its Chinese language school. We often invite MDN teachers to go abroad to lead teacher training classes and pass along their experience. For example, we worked with the MDN to hold teacher training programs in the Philippines.

Q: The craze for learning Chinese has lasted for many years. Where is it leading?

A: The magnetism of mainland China will only expand the market for learning Chinese. The demand for teaching both traditional and simplified characters will only grow.

Considering that there has even been some discussion on the mainland about returning to traditional characters, we can feel very confident about the future of teaching traditional characters. Ultimately, the lack of logical integrity and the inability of readers to understand older texts are problems that simplified characters will never be able to overcome.

In the next stage we want to expand beyond overseas Chinese communities in our push to teach Chinese, allowing even more people to gain an appreciation for the wonders of the Chinese language.

@List.jpg?w=522&h=410&mode=crop&format=webp&quality=80)